All aboard the Bob Dylan express! How Rolling Thunder revved round America

When Dylan chanced upon a huge Roma gathering in France, he was transfixed – and formed his own travelling supergroup. As Martin Scorsese brings its ragtag magic to screens, we hitch a ride back to 75

Richard Williams

The Guardian

Tue 11 Jun 2019

In May 1975, his marriage breaking up, Bob Dylan spent six weeks in the south of France. His host, an artist named David Oppenheim, had recently provided a painting for the back cover of Blood on the Tracks, an album of seemingly confessional songs that had taken Dylan back to the top of the charts. Critics acclaimed its songs as evidence that, after almost a decade of straying from the straight and narrow, he was prepared once again to bare his soul.

But Dylan, as usual, was restless. A year earlier he had toured for the first time since his motorcycle accident in 1966, reuniting with the Band, his old accomplices. It had been a commercially successful but artistically sterile experience. He was looking for something new, and he found it when Oppenheim introduced him to the Camargue, a land of salt marshes, wild horses and a village called Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. Celebration … Roma girls dress a statue of St Sarah at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

There he witnessed the annual gathering of Roma, arriving from across Europe for the spring festival in celebration of Saint Sarah. Later he claimed that it was after spending his 34th birthday watching them carry her effigy from the sea to the shore, and listening to them sing at night, that he had a dream in which the song One More Cup of Coffee came to him, fully formed. But it was the more general sense of a travelling community with a natural way of expressing its culture that inspired the next and typically unexpected phase of his career.

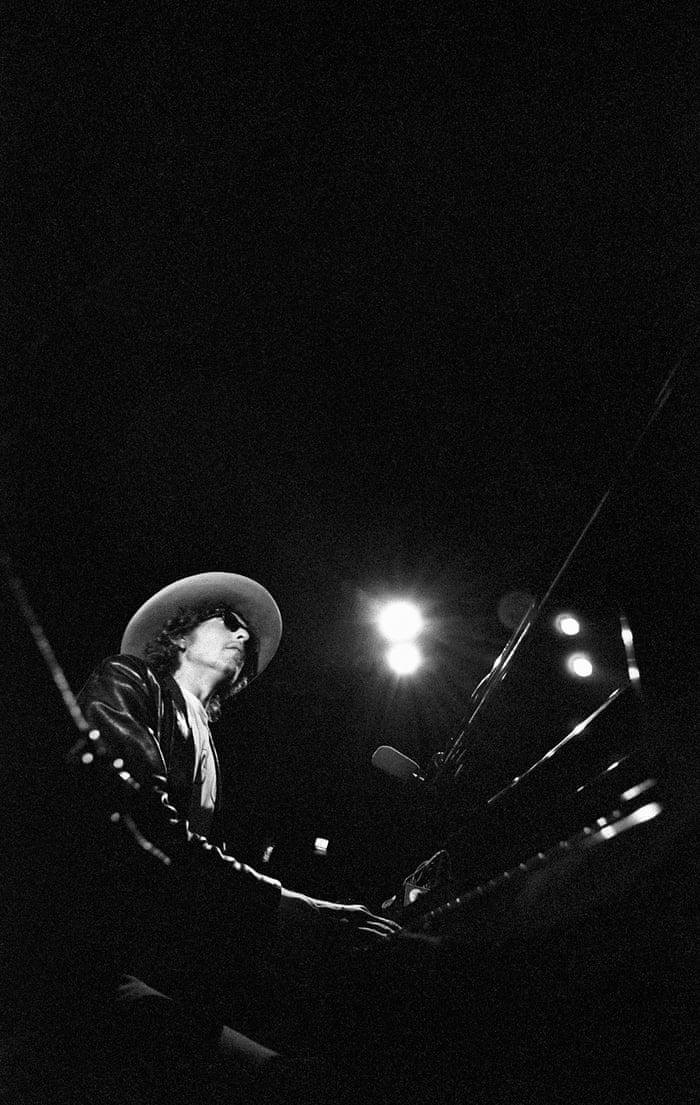

“There was a Rolling Thunder energy and that was his invention,” Joan Baez says in Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, the documentary by Martin Scorsese released this week on Netflix. Using verite and concert footage, some of it first seen in Dylan’s long-buried feature film Renaldo and Clara, Scorsese reframes that energy while adding a layer of meta-reality that reflects Dylan’s enduring fascination with masks, disguises and alternative facts.

After his return from France, Dylan based himself in a Greenwich Village apartment and underwent a full reimmersion in the folk scene from which he had emerged a dozen years earlier. In the clubs and coffee houses, fellow performers clustered around him: old friends like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Bobby Neuwirth and Roger McGuinn and new ones such as the violinist Scarlet Rivera, whom Dylan had approached when he saw her carrying her instrument case on the street.

Some of them took part in the sessions for his new album, Desire, with Rivera adding a touch of Romany abandon as she wound her fiddle lines around Dylan’s voice. The songs ranged from a demand for the release of Rubin “The Hurricane” Carter, a boxer imprisoned on a murder charge, to a startlingly direct address to his wife, Sara. The unit stayed together, accumulating extra members, as plans were made for taking the show on the road.

Dylan wanted to perform, but he needed to escape from the music industry machine. If there were precedents for the adventure, they include the transcontinental bus trips made by Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters in the mid-60s, the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus in 1968 and Paul McCartney’s decision to exorcise the ghost of Beatlemania by taking Wings out on a small-scale, low-key, unannounced tour of British colleges in 1972.

Outside, the world was a turbulent and bloody mess. The Watergate scandal was still echoing as the last US forces in Vietnam were airlifted from the roof of the Saigon embassy. The Khmer Rouge had taken over in Cambodia and civil wars were raging in Lebanon and Angola. Dylan had long since withdrawn from overt political commentary, but there was a statement implicit in his decision – made as America geared itself up for its Bicentennial celebrations – to open the tour in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where the Pilgrim Fathers had arrived in 1620 and survived a hard first winter in their new settlement only through the kindness of the indigenous Wampanoag tribe.

New recruits included the singer Ronee Blakley, direct from starring in Robert Altman’s Nashville, the guitarist T-Bone Burnett, and the poet Allen Ginsberg. Having decided to film the tour – on and off stage – for Renaldo and Clara, a movie in which all the participants would be ascribed fictional roles, Dylan recruited the young playwright Sam Shepard to provide a screenplay. He added Baez, who would share scenes in the film with Sara Dylan, the woman for whom Dylan had left her 10 years earlier. Others drawn “like metal shavings to a magnet”, as Shepard would write in his Rolling Thunder Logbook, included Joni Mitchell, Ronnie Hawkins, Harry Dean Stanton and Mick Ronson, the ex-Spider from Mars. Jacques Levy, an off-Broadway theatre director with whom Dylan had been writing lyrics, devised the show’s structure.

“This was Dylan at his most generous,” Burnett observed in his foreword to Shepard’s book. “He had offered his stage to old friends, new acquaintances and in some cases complete strangers.” At the wheel of his Winnebago, Dylan drove some of the troupe while others were transported in a converted Greyhound bus. Ginsberg and his lover Peter Orlovsky acted as baggage porters even after the poet’s slot was axed in rehearsals, when Levy slashed the eight-hour running order in half.

“Welcome to your living room,” Bob Neuwirth told the audience every night before introducing the first of several guest spots. Some of Dylan’s performances were professionally recorded and are included in a new 14-CD box set. The revelations include a wonderfully tender solo delivery of Easy and Slow, a song picked up during his encounters with Irish folk musicians, and several magnificent duets with Baez, their voices fitting together much better than they ever had in their younger days.

As for Renaldo and Clara, whose intended sources of inspiration (according to Shepard) included Marcel Carné’s Les Enfants du Paradis and François Truffaut’s Tirez sur le Pianiste, Dylan spent a couple of years working on a four-hour version that fascinated some, mystified many more, and disappeared soon after its release in 1978. The concert and backstage footage – although not the dramatised sequences – now forms part of Scorsese’s film, along with several mischievous red herrings. It’s a stylish palimpsest beneath which the ghostly outline of the original film can be clearly discerned, although the several enigmatic absences include that of Sara, who had the part of Clara, opposite Dylan’s Renaldo.

The new film’s highlights include the night Baez adopted the whiteface makeup and hat bedecked with flowers and feathers that Dylan had worn throughout the tour; the morning Dylan and Ginsberg paid homage at Jack Kerouac’s grave; and the afternoon a room full of middle-aged Jewish women, who thought they had gathered for a mahjong session, found themselves listening in bemusement as Ginsberg read the Kaddish he had written for his own Jewish mother. A very on-her-mettle Joni Mitchell runs through Coyote, the song about her affair with Shepard, in Gordon Lightfoot’s living room in Toronto while Dylan and McGuinn watch her fingers, trying to pick up the chords. Some of Dylan’s stage performances, notably a howling, full-throttle Isis, are colossal in their blazing passion.

The Rolling Thunder Revue ran against the grain of the music industry. As a business plan, it was never likely to catch on. The biggest concerts, at Madison Square Garden and the Houston Astrodome, were benefits for boxer Rubin Carter’s defence fund. A second set of shows, in the spring of 1976, visited larger venues but petered out with a final concert to a half-empty convention centre in Salt Lake City.

A year later, amid the stirrings of punk in England, something of its freewheeling methodology was revived by the first Stiff Records tour, in which Ian Dury, Elvis Costello and Nick Lowe travelled together, sharing rhythm sections and shuffling the running order. Closer in musical terms was Bruce Springsteen’s Seeger Sessions project of 2005, with its onstage informality and a mixture of original and traditional songs.

“Life isn’t about finding yourself, or finding anything – it’s about creating yourself,” Dylan says in a new interview in the film. By the time Renaldo and Clara appeared, he was making a new album, Street Legal, and preparing for a marathon world tour with a different lineup, still powerful but retaining little of Rolling Thunder’s raggle-taggle spirit. And in January 1979, a few weeks after that band’s final show, another encounter with Christianity – this time of the evangelical variety – gave him the cue for the next phase of his life. Around the bend, a slow train was coming.

• Rolling Thunder Revue will launch on Netflix and in selected cinemas on 12 June. Bob Dylan: Rolling Thunder Revue, the 1975 Live Recordings box set is out now.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/jun/11/bob-dylan-rolling-thunder-revue-martin-scorsese

Tue 11 Jun 2019

In May 1975, his marriage breaking up, Bob Dylan spent six weeks in the south of France. His host, an artist named David Oppenheim, had recently provided a painting for the back cover of Blood on the Tracks, an album of seemingly confessional songs that had taken Dylan back to the top of the charts. Critics acclaimed its songs as evidence that, after almost a decade of straying from the straight and narrow, he was prepared once again to bare his soul.

But Dylan, as usual, was restless. A year earlier he had toured for the first time since his motorcycle accident in 1966, reuniting with the Band, his old accomplices. It had been a commercially successful but artistically sterile experience. He was looking for something new, and he found it when Oppenheim introduced him to the Camargue, a land of salt marshes, wild horses and a village called Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. Celebration … Roma girls dress a statue of St Sarah at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

There he witnessed the annual gathering of Roma, arriving from across Europe for the spring festival in celebration of Saint Sarah. Later he claimed that it was after spending his 34th birthday watching them carry her effigy from the sea to the shore, and listening to them sing at night, that he had a dream in which the song One More Cup of Coffee came to him, fully formed. But it was the more general sense of a travelling community with a natural way of expressing its culture that inspired the next and typically unexpected phase of his career.

“There was a Rolling Thunder energy and that was his invention,” Joan Baez says in Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, the documentary by Martin Scorsese released this week on Netflix. Using verite and concert footage, some of it first seen in Dylan’s long-buried feature film Renaldo and Clara, Scorsese reframes that energy while adding a layer of meta-reality that reflects Dylan’s enduring fascination with masks, disguises and alternative facts.

After his return from France, Dylan based himself in a Greenwich Village apartment and underwent a full reimmersion in the folk scene from which he had emerged a dozen years earlier. In the clubs and coffee houses, fellow performers clustered around him: old friends like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Bobby Neuwirth and Roger McGuinn and new ones such as the violinist Scarlet Rivera, whom Dylan had approached when he saw her carrying her instrument case on the street.

Some of them took part in the sessions for his new album, Desire, with Rivera adding a touch of Romany abandon as she wound her fiddle lines around Dylan’s voice. The songs ranged from a demand for the release of Rubin “The Hurricane” Carter, a boxer imprisoned on a murder charge, to a startlingly direct address to his wife, Sara. The unit stayed together, accumulating extra members, as plans were made for taking the show on the road.

Dylan wanted to perform, but he needed to escape from the music industry machine. If there were precedents for the adventure, they include the transcontinental bus trips made by Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters in the mid-60s, the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus in 1968 and Paul McCartney’s decision to exorcise the ghost of Beatlemania by taking Wings out on a small-scale, low-key, unannounced tour of British colleges in 1972.

Outside, the world was a turbulent and bloody mess. The Watergate scandal was still echoing as the last US forces in Vietnam were airlifted from the roof of the Saigon embassy. The Khmer Rouge had taken over in Cambodia and civil wars were raging in Lebanon and Angola. Dylan had long since withdrawn from overt political commentary, but there was a statement implicit in his decision – made as America geared itself up for its Bicentennial celebrations – to open the tour in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where the Pilgrim Fathers had arrived in 1620 and survived a hard first winter in their new settlement only through the kindness of the indigenous Wampanoag tribe.

New recruits included the singer Ronee Blakley, direct from starring in Robert Altman’s Nashville, the guitarist T-Bone Burnett, and the poet Allen Ginsberg. Having decided to film the tour – on and off stage – for Renaldo and Clara, a movie in which all the participants would be ascribed fictional roles, Dylan recruited the young playwright Sam Shepard to provide a screenplay. He added Baez, who would share scenes in the film with Sara Dylan, the woman for whom Dylan had left her 10 years earlier. Others drawn “like metal shavings to a magnet”, as Shepard would write in his Rolling Thunder Logbook, included Joni Mitchell, Ronnie Hawkins, Harry Dean Stanton and Mick Ronson, the ex-Spider from Mars. Jacques Levy, an off-Broadway theatre director with whom Dylan had been writing lyrics, devised the show’s structure.

“This was Dylan at his most generous,” Burnett observed in his foreword to Shepard’s book. “He had offered his stage to old friends, new acquaintances and in some cases complete strangers.” At the wheel of his Winnebago, Dylan drove some of the troupe while others were transported in a converted Greyhound bus. Ginsberg and his lover Peter Orlovsky acted as baggage porters even after the poet’s slot was axed in rehearsals, when Levy slashed the eight-hour running order in half.

“Welcome to your living room,” Bob Neuwirth told the audience every night before introducing the first of several guest spots. Some of Dylan’s performances were professionally recorded and are included in a new 14-CD box set. The revelations include a wonderfully tender solo delivery of Easy and Slow, a song picked up during his encounters with Irish folk musicians, and several magnificent duets with Baez, their voices fitting together much better than they ever had in their younger days.

As for Renaldo and Clara, whose intended sources of inspiration (according to Shepard) included Marcel Carné’s Les Enfants du Paradis and François Truffaut’s Tirez sur le Pianiste, Dylan spent a couple of years working on a four-hour version that fascinated some, mystified many more, and disappeared soon after its release in 1978. The concert and backstage footage – although not the dramatised sequences – now forms part of Scorsese’s film, along with several mischievous red herrings. It’s a stylish palimpsest beneath which the ghostly outline of the original film can be clearly discerned, although the several enigmatic absences include that of Sara, who had the part of Clara, opposite Dylan’s Renaldo.

The new film’s highlights include the night Baez adopted the whiteface makeup and hat bedecked with flowers and feathers that Dylan had worn throughout the tour; the morning Dylan and Ginsberg paid homage at Jack Kerouac’s grave; and the afternoon a room full of middle-aged Jewish women, who thought they had gathered for a mahjong session, found themselves listening in bemusement as Ginsberg read the Kaddish he had written for his own Jewish mother. A very on-her-mettle Joni Mitchell runs through Coyote, the song about her affair with Shepard, in Gordon Lightfoot’s living room in Toronto while Dylan and McGuinn watch her fingers, trying to pick up the chords. Some of Dylan’s stage performances, notably a howling, full-throttle Isis, are colossal in their blazing passion.

The Rolling Thunder Revue ran against the grain of the music industry. As a business plan, it was never likely to catch on. The biggest concerts, at Madison Square Garden and the Houston Astrodome, were benefits for boxer Rubin Carter’s defence fund. A second set of shows, in the spring of 1976, visited larger venues but petered out with a final concert to a half-empty convention centre in Salt Lake City.

A year later, amid the stirrings of punk in England, something of its freewheeling methodology was revived by the first Stiff Records tour, in which Ian Dury, Elvis Costello and Nick Lowe travelled together, sharing rhythm sections and shuffling the running order. Closer in musical terms was Bruce Springsteen’s Seeger Sessions project of 2005, with its onstage informality and a mixture of original and traditional songs.

“Life isn’t about finding yourself, or finding anything – it’s about creating yourself,” Dylan says in a new interview in the film. By the time Renaldo and Clara appeared, he was making a new album, Street Legal, and preparing for a marathon world tour with a different lineup, still powerful but retaining little of Rolling Thunder’s raggle-taggle spirit. And in January 1979, a few weeks after that band’s final show, another encounter with Christianity – this time of the evangelical variety – gave him the cue for the next phase of his life. Around the bend, a slow train was coming.

• Rolling Thunder Revue will launch on Netflix and in selected cinemas on 12 June. Bob Dylan: Rolling Thunder Revue, the 1975 Live Recordings box set is out now.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/jun/11/bob-dylan-rolling-thunder-revue-martin-scorsese

No comments:

Post a Comment