Camden New Journal

17 October, 2019

IT was a lifetime’s work – and the boxes of negatives were just about all that survived a devastating fire that tore through photographer Freddy Warren’s Grafton Chambers flat in 2010.

The 71-year-old, who had taken seminal shots of the biggest names in jazz, lost his life in a blaze at his home in Euston. It destroyed his flat – but his nephew, Simon Whittle, managed to save thousands of images that chart his life as a Fleet Street photographer by day and as a jazz aficionado by night.

They revealed a man whose lens gave him unprecedented access to capture some of the biggest names ever to perform at Ronnie Scott’s club. Now a sample of his extensive archive has been published by Reel Art Press, and is the subject of a major retrospective at the Barbican.

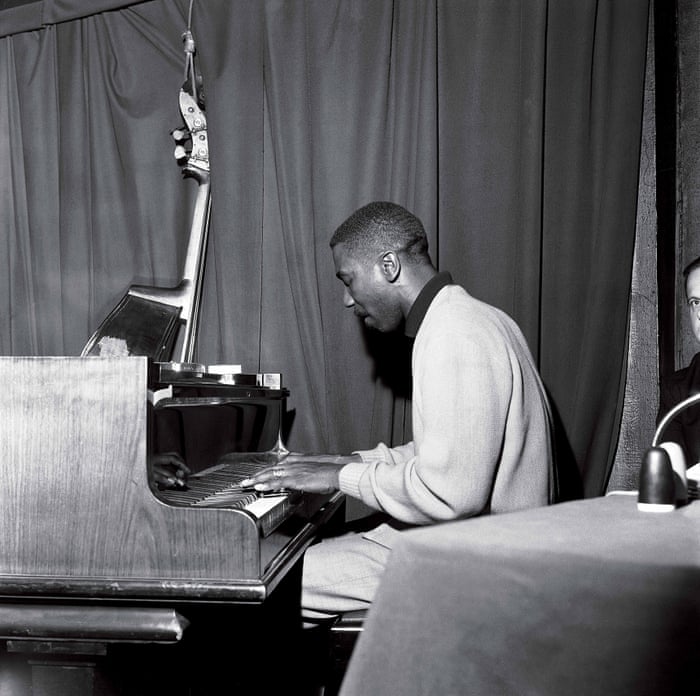

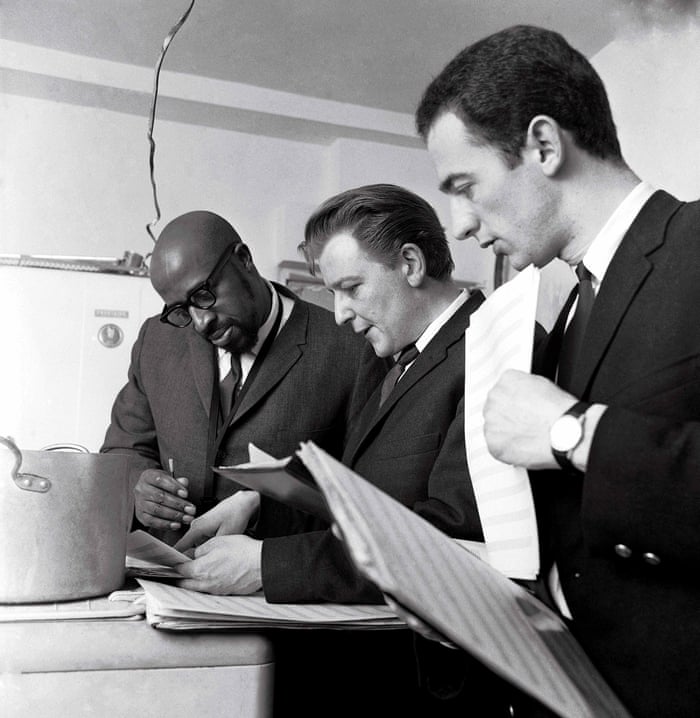

Ronnie Scott’s 1959–69 is a previously unseen archive that captures the life and times of the legendary venue, all shot by a self-taught photographer whose charm and skill got him a front-of-house seat and backstage access to capture stunning pictures of Soho and jazz culture in the 60s.

They include Ronnie Scott surveying the building site that would become the club in Frith Street, warming his hands over a brazier of off-cuts, interspersed with shots of musicians rehearsing, performing or just hanging out.

Freddy took pictures regularly over a 10-year period, capturing the very essence of Ronnie’s – and the images show not only what a superb eye he had for a shot, but illuminate the inside story of the club during a period when some of the greatest musicians and performers of the 20th century would appear at the Soho venue.

Among the negatives rescued by Simon from his burnt-out home include performance shots and off-stage pictures of the likes of Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Duke Ellington, Nina Simone and more.

Born in 1935, Freddy grew up in Hounslow and after serving in the RAF began a career taking photographs.

“He really became a photographer by accident,” says Simon. “He bought a camera off my uncle Cyril and discovered he had an intrinsic talent for it.

“He had got into jazz while he served in the RAF, and that acted as a catalyst. Freddy had first gone to Ronnie Scott’s when a RAF jazz band made up of his friends was booked to play there. He went along with his camera and took some shots.”

Ronnie Scott during the building of the club

Ronnie Scott during the building of the club

He met photographers Eric Jelly and Mark Sharratt, who worked for Melody Maker, and after they saw his images, they said he had a job waiting for him when he left the RAF.

He worked as an assistant in their studio Photography 33, based in Soho, before working in Fleet Street during the day for the Daily Mirror and Daily Sketch – then heading to Ronnie’s each night to take photos of jazz musicians.

“He never got anyone to pose,” says Simon. “What he did at Ronnie’s was off the cuff, taking pictures as they were playing. He never directed anything, he just moved around and took the shots he wanted, the shots he knew would work.”

His approach was such that some of the famously tough characters in the jazz world took to him – likes of Miles Davis and Stan Getz, who had reputations, admired what he did.

“Maybe he gave as good as he got,” says Simon. “Miles was a friend – Freddy recalled how Miles once bought a watch off him. He also signed albums for Freddy, leaving his phone number and address in America with an open invitation to come and visit.”

Simon was close to his uncle and was aware of his passion for jazz.

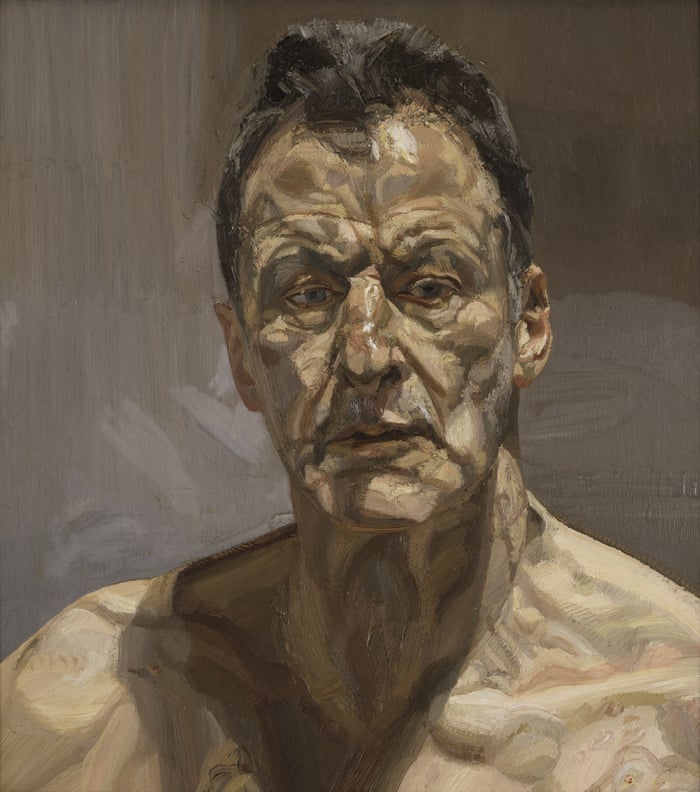

Buddy Rich

Buddy Rich

“Uncle Fred had an amazing hi fi system and a massive collection of LPs,” he recalls.

When Simon came to help clear up following Freddy’s death, he found boxes in an office at the back of the badly damaged flat where the fire had not quite reached.

“There were shelves and shelves with thousands of negatives,” he says.

“I had no idea what would be in there. I knew he had taken pictures of jazz world but I didn’t know how many. I discovered what was his life’s work. I started going through them, trying to sort them out, making envelopes of different people like Davis, Tubby Hayes, Nina Simone.”

As well as his work at Ronnie’s, his life as a Fleet Street photographer saw him gain access to the stars of the era – the likes of Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers, The Rolling Stones, the royal family and many more.

“He was well known for his work in the 60s and 70s and I know he wanted his pictures shown but never really put his mind to it,” adds Simon.

“He would be pleased as punch to have an exhibition on at The Barbican.”

• Ronnie Scott’s 1959-69 Photography by Freddy Warren is at Barbican Library, Silk Street, Barbican, EC2Y 8DS until January 4, 2020. Admission Free. The book accompanying the show is Photographs by Freddy Warren, Reel Art Press, £29.95