Jacques Tourneur's Out of the Past - the quintessential noir

Claustrophobic and nihilistic, a disturbing universe with dramatic lighting. An award-winning poet explains why he immersed himself in film noir for his Booker-prize shortlisted debut novel

Robin Robertson

The Guardian

Mon 12 Nov 2018

I watched film noir before I knew it had a name, growing up with these black-and-white B-movies that appeared at odd hours on 70s television. It was only when I moved from Scotland to London that I saw them, properly, on the big screen, and understood them for what they were: the cinema of the city, steeped in the city’s fascination and fear. All the ambivalence I felt arriving in London as a young outsider was there in the mood and the images of these films, and I soon learned why they spoke to me so directly. These classic 40s and 50s movies – which seem like a distinctly American art form, like blues or jazz – were mostly not made by Americans but by emigres: Jewish directors and cinematographers who had fled Nazi Germany and ended up in Hollywood, bringing their expressionist aesthetic and their deep terrors to celluloid. These refugee artists were among the “huddled masses” that built America; the kind of people that are now, it seems, unwelcome.

Despite living most of my life in cities, I’ve never really written about them. When I decided I would, I knew it had to be US cities, immediately after the war, when the American dream started to falter; that the soundtrack would be jazz, and that much of the tonal qualities would come from film noir. I watched about 500 films before writing The Long Take – listening for the idiom, watching the camera techniques, the editing, working out the geography of the city location shots – and it was these 10 movies that I kept returning to: the ones that, for me, capture the classic spirit and style of this brief but hugely influential cycle of films.

Mon 12 Nov 2018

I watched film noir before I knew it had a name, growing up with these black-and-white B-movies that appeared at odd hours on 70s television. It was only when I moved from Scotland to London that I saw them, properly, on the big screen, and understood them for what they were: the cinema of the city, steeped in the city’s fascination and fear. All the ambivalence I felt arriving in London as a young outsider was there in the mood and the images of these films, and I soon learned why they spoke to me so directly. These classic 40s and 50s movies – which seem like a distinctly American art form, like blues or jazz – were mostly not made by Americans but by emigres: Jewish directors and cinematographers who had fled Nazi Germany and ended up in Hollywood, bringing their expressionist aesthetic and their deep terrors to celluloid. These refugee artists were among the “huddled masses” that built America; the kind of people that are now, it seems, unwelcome.

Despite living most of my life in cities, I’ve never really written about them. When I decided I would, I knew it had to be US cities, immediately after the war, when the American dream started to falter; that the soundtrack would be jazz, and that much of the tonal qualities would come from film noir. I watched about 500 films before writing The Long Take – listening for the idiom, watching the camera techniques, the editing, working out the geography of the city location shots – and it was these 10 movies that I kept returning to: the ones that, for me, capture the classic spirit and style of this brief but hugely influential cycle of films.

Out of the Past (1947) dir: Jacques Tourneur

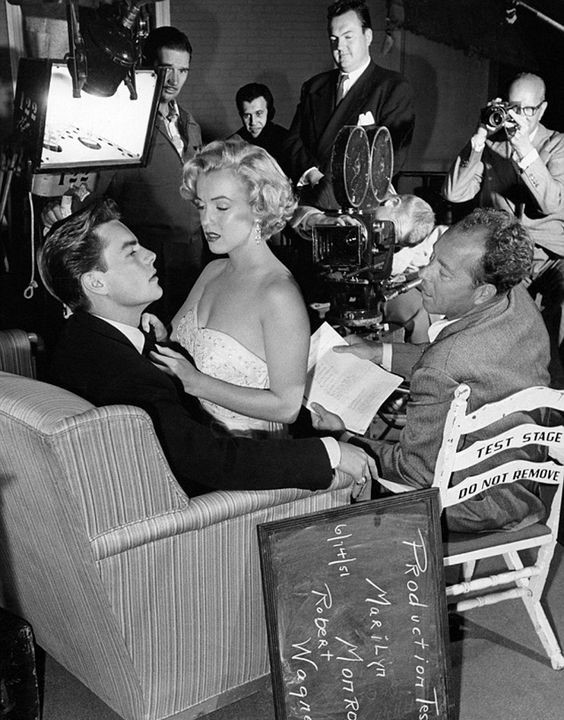

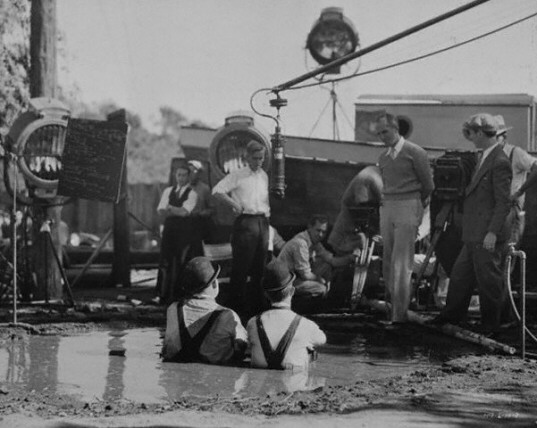

Regarded by many as the quintessential noir, Out of the Past offers most of the classic elements of the style: voiceovers, flashbacks, a labyrinthine plot, a doomed male obsessive and a femme fatale – with Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer playing these roles effortlessly. In a tragedy told as a dream, these complex, mysterious characters emerge from the shadows to deliver their lines: “Is there a way to win?” says Greer’s character, and Mitchum deadpans back: “There’s a way to lose more slowly.” I used that perfectly weighted line as the subtitle to The Long Take.

Brute Force (1947) dir: Jules Dassin

A prison stands in for the city: a walled theatre of meaningless degradation and punishment, where the only language left is violence. The carceral imagery of Brute Force was certainly something I drew on in my descriptions of New York and Los Angeles. As much an existential drama as a prison-break movie, this is a claustrophobic and nihilistic film lit up by wonderful acting. It’s an ensemble piece like a stage play, brilliantly cast – inside and out. Burt Lancaster is superb in the lead role, but even he is upstaged by Hume Cronyn as the sadistic, power-hungry Captain Munsey, who beats a prisoner with a rubber hose to a recording of Wagner’s Tannhäuser.

Ride the Pink Horse (1947) dir: Robert Montgomery

A little-known non-urban noir, with Robert Montgomery directing himself as Gagin, a war veteran on a mission to New Mexico to avenge the death of a fellow soldier at the hands of a war profiteer. The embittered ex-soldier coming back from slaughter to find his country corrupted was a reality of late-40s America, and a recurrent theme in early noirs, and I was influenced by aspects of the plot-line here and in other films that address the problems of veterans, such as Act of Violence and Crossfire. A stunning long-take opening sequence in a bus station establishes Gagin’s character as driven, exhausted, alienated and seemingly stripped of all emotion. It is only when he encounters the carnival horses of the town’s carousel, and the kindness of the locals, that the fiesta – and the symbolic wheel of life – can begin to turn.

T-Men (1947) dir: Anthony Mann

After the stilted prologue that encourages us to see the film as a fact-based story of the brave actions of US treasury agents, the real noir underworld quickly emerges – particularly in the extraordinarily elegant and stylised steam-bath murder. Along with The Big Combo, this is one of the most visually stunning films in the cycle, with cinematographer John Alton filling each frame with contrast and tension, deep focus and unorthodox camera angles. I hoped to have Alton at my shoulder while I was writing, for his painterly eye and his gift for combining economy with sudden beauty.

Criss Cross (1949) dir: Robert Siodmak

Opening with an amazing aerial shot of downtown Los Angeles, slowly descending to a nightclub parking lot where the lovers – Burt Lancaster and Yvonne De Carlo – are locked in a secret embrace, Criss Cross is an 88-minute plunge into their fated world, a drop into doom. Despite much of it being shot in daylight (around Bunker Hill, a now vanished part of Los Angeles), Criss Cross is a dark, fatalistic tragedy. I have my character Walker in The Long Take visiting the shoot above the Hill Street tunnels (which feature on the book’s cover), and talking to the director.

Gun Crazy (1950) dir: Joseph H Lewis

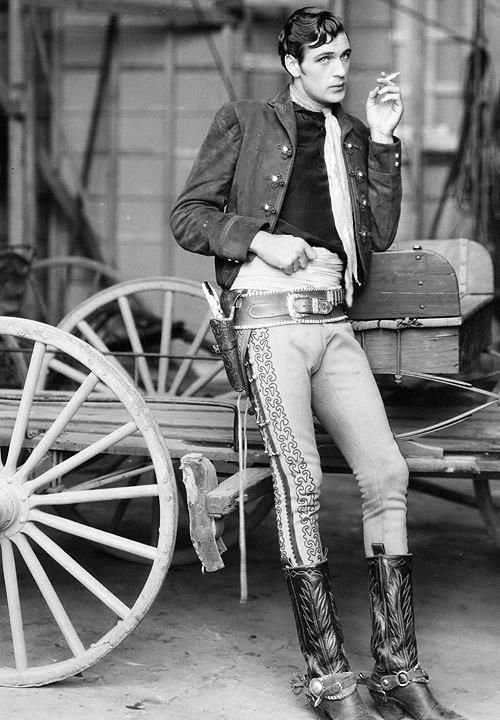

Seen by some as the precursor to Bonnie and Clyde, this is the story of Bart, a gentle, decent man with an unhealthy obsession with guns. When he encounters Annie Laurie in a sharp-shooting sideshow, the pas de deux of sex and violence begins. She wants more things, nicer things, and leads him – her co-dependent in addiction – into increasingly serious crimes. As the film develops into a cross between a road movie and a western, their first bank robbery is an exquisitely staged long-take shot from inside their car. It’s a perfect expression of their amour fou, their fugitive world where sex and death are on the same line: “We go together … like guns and ammunition.” What is extraordinary is that it’s not cinematic grandstanding, but a tiny naturalistic drama that feels like an improvised film within a film: an improvisation embedded in an edited, scripted construct.

Night and the City (1950) dir: Jules Dassin

Along with The Third Man, this is a great British noir, the compulsive, concentrated morality tale of Harry Fabian, a spivvy American hustler in London who wants to make it big, played magnificently by Richard Widmark – volatile and paranoid, giggling insanely. It co-stars the fabulous Gene Tierney and has a first-rate British cast, including Googie Withers and Herbert Lom. The film’s director, Dassin – thrown out of Hollywood by HUAC and McCarthy – turns postwar London into an expressionist trap, a nightmare city teeming with cripples, beggars and informers, like something out of Kurt Weil or Tod Browning. Filmed in 1949, the final scene under Hammersmith Bridge could have been shot yesterday. I live 10 minutes away, and I think about this film every time I walk along that stretch of river.

The Big Combo (1955) dir: Joseph H Lewis

Directed by the maverick Joseph H Lewis, with cinematography again from Alton, The Big Combo includes more dingy sexuality, casual violence and repressed, sadomasochistic relationships than any other noir. Cornel Wilde is the moral touchstone: a decent cop who goes too far into this vile world, trying to rescue the pure, defiled Susan Lowell (Jean Wallace), only to suffer torture by hearing aid. An inventive, deeply atmospheric film: dark, disturbing and beautifully shot. Walker watches the movie three times in The Long Take: “He saw its hard lines all the way home through the fog: / the raking headlamp opening up a wall, the shadows / tightening in around this spoon of light that’s dragged / across the metal doors, snapped back to darkness.”

Kiss Me Deadly (1955) dir: Robert Aldrich

Made in 22 days in and around Los Angeles, Kiss Me Deadly is about speed and violence, fast cars and freeways: a world of moral decomposition, corruption and brutality, with nuclear apocalypse as the only cleansing agent. From the opening credits, with “DEADLY” then “KISS ME” scrolling down over the speeding road, this is a highly sensory film about the interaction of the human and the machine. Brilliantly photographed by Ernest Laszlo, the movie is visually jagged, angular and out of kilter, with its characters alienated and dehumanised, disorientated by their landscape. It is a film of its time: frenetic, fractured and deeply paranoid. We also see into the future, with the recognition of a social selfishness and greed that was to become endemic. As Walker says in the The Long Take: “When we want everything and give back nothing / the otherworld will be unlocked, and our whole world taken away.”

Touch of Evil (1958) dir: Orson Welles

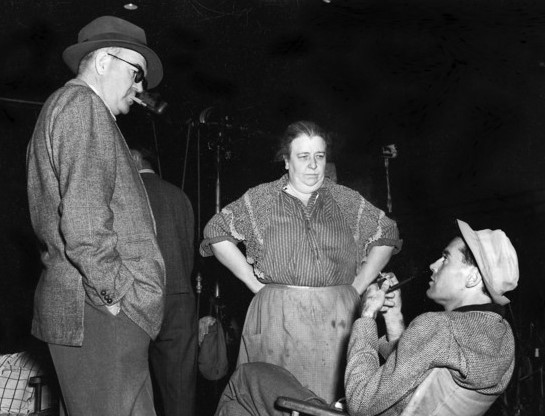

The film opens with a celebrated long take tour-de-force: an unbroken three-minute craning and tracking night shot where a time bomb is placed in the trunk of a car, exploding just across the busy US-Mexico border. Unlike those in Ride the Pink Horse or Gun Crazy, the long take here is almost operatic in its certainty. Like many of Welles’s films, Touch of Evil was taken out of his hands and butchered by studio chiefs. Forty years later, it was rebuilt by the great editor Walter Murch, based on all existing material and closely following the Welles memo. Salvaged, and dramatically improved, it is still a flawed work – appropriately, perhaps, as it’s about a flawed man. The final shot – of Quinlan floating dead in a filthy canal – is a wholly appropriate sign-off to the noir cycle.

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/nov/12/a-pas-de-deux-of-sex-and-violence-a-poets-guide-to-film-noir#comments

At a time when the term 'noir' is overused to describe any low-lit television thriller with a troubled protagonist hunting down a borderline psychopath (preferably in Swedish or Danish with subtitles), this is a nice little intro, though he overplays - as is common - the standard Film Studies/Pop Culture view that the style was down to the work of German emigres during and after World War II.

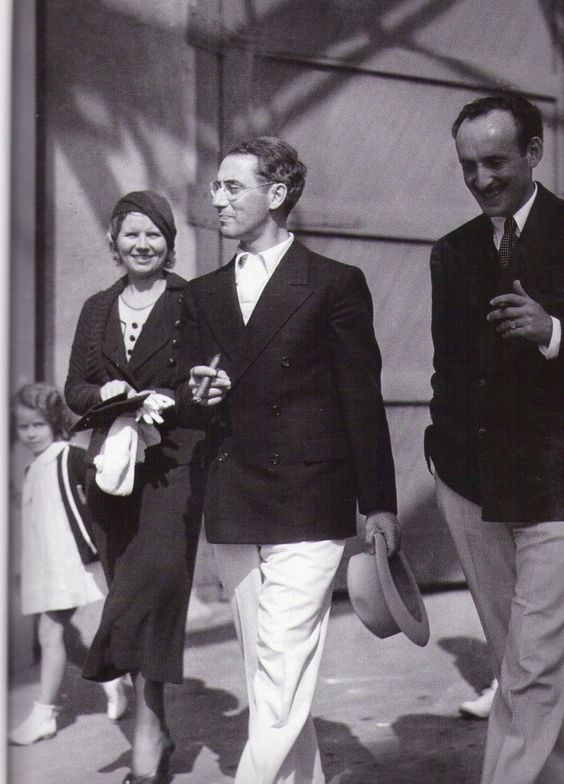

Expressionism had hit America long before noir. It was so popular in the 1920s, for example, that the great German director F W Murnau was invited to Hollywood to make Sunrise, a 'realistic' romantic tale using expressionistic techniques. John Ford, who would be familiar with the style from years of working in the cinema and who was an admirer of the work of Eugene O'Neil, the Irish American playwright influenced by European expressionism on stage, uses it to great effect in The Informer and in that quintessential Western, Stagecoach - a huge influence on Welles - where there isn't a city in sight.

Moreover, the low lighting and use of fog/smoke were often features of taut crime features made at Warner Brothers to disguise their low budgets - and Warners became the home to several significant noirs.

The simple timeline approach negates the influence of literature on the genre or - as Robertson mentions - of World War II. Some of the best noirs feature men broken by the war (Dmytryk's Crossfire, for example, where ex-soldiers seem unwilling or unable to return to their former lives and exist in a dreamscape of darkened rooms, circling around a nasty anti-semitic crime.

Robertson refers to the use of the femme fatale, an attractive woman wrought to lure the 'hero' into a deeper and more disturbing series of events than at first he realises. A throwback to gothic literature and beyond, to be sure, but also symbolic of the threat to masculinity felt by males when they returned from World War II to find that women had taken their jobs and were no longer prepared to be home-makers.

The timeline view also does no credit to the influence of French films like Pepe Le Moko or Daybreak or indeed, to the work of later French film-makers which could be labelled as noir, like Jean-Pierre Melville's crime films, like Le Samourai.

I could quibble about Robertson's selection, of course. While Out of the Past has to be on there, I would need Siodmak's The Killers, the afore-mentioned Crossfire, Pepe le Moko and Daybreak, Hawks' The Big Sleep, Cromwell's Dead Reckoning, Hitchcock's Strangers on a Train, Reed's Odd Man Out (I'd have The Third Man, but it gets a nod in the article) and as a great 'latter day' noir, Ivan Passer's (look: another emigre!) Cutter's Way. Trouble is, I wouldn't want to drop any of Robertson's films: I'd need a list of at least 30!