Influence, invention, and the legacy of Leon Redbone

Megan Pugh

Oxford American

19 March 2019

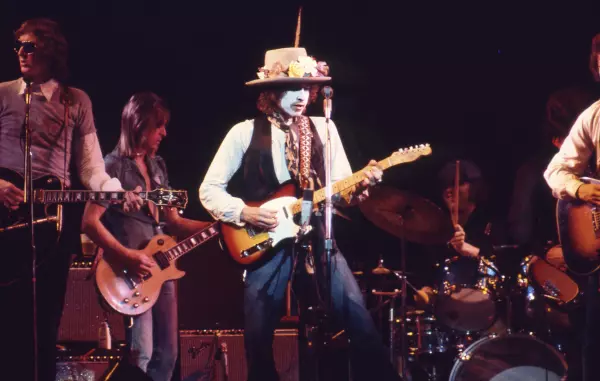

Leon Redbone’s first guitar, or at least the first one anyone seems to remember seeing after he emerged on the Toronto folk scene in the late 1960s, was a Harmony Sovereign, transformed according to his vision. He painted the headstock to cover up the brand name and drew a meticulous pattern around the edges of the soundboard that, from the audience, resembled inlay. He used it to play old tunes from the 1920s and ’30s—country blues, ragtime—his voice shifting from molasses crooning to gravelly yowls. Dressed in the natty suits and ties of a Mississippi riverboat gambler, a Kentucky colonel, a dignified bluesman, or a Jimmie Rodgers–styled railroad brakeman with the right cap for the job, Redbone invited audiences into a tent show of American musical history where folks like Rodgers, Blind Blake, Emmett Miller, and Jelly Roll Morton could still draw crowds. His face was partially obscured by a hat and dark glasses. Sometimes he’d set a piece of fruit on the stool beside him: comically mute accompaniment. Redbone bought other guitars as his career took off, but his artistic ethos remained constant: Cover up some origins and conjure others. Craft an illusion and make it real. Bring the past into the present. Look at things slant. Do something beautiful, be careful about it, and keep your sunglasses on.

“The only thing that interests me,” said Redbone in a 1991 interview, “is history, reviewing the past and making something out of it.” He came of age in an era when plenty of musicians were looking backward. But where the folkies dusted off old songs like sacred artifacts, Redbone settled into the past like it was a familiar rocking chair, leisurely tuning his guitar with a sly growl of “Rise, Lazarus” or using it as a paddle to traverse an imaginary lazy river. Onstage, he took photographs of his audience, so that they—not he—became objects of attention. He blew bubbles, built a small table outfitted with an exploding device that he’d set off during “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” and engaged band members in banter lifted directly from the vaudeville era. Other jokes unfolded more quietly, with deadpan delivery—“This song has been around for over a hundred years,” the clarinetist Dan Levinson remembers him saying, “so you’ve had plenty of time to learn it. If you know the words, please hum along”—or small, masterful movements: a cock of the head, an exaggerated waggle of a hat brim. For years, Redbone would play a recording of the Hungarian opera singer Sári Barabás as his hands danced along, making shadows against a white cardboard screen.

Musically speaking, Redbone wasn’t as experimental as Tom Waits or Frank Zappa, but on the strength and strangeness of his persona, he was often compared to them. “He manifests himself as some kind of link between Robert Johnson and Richard Brautigan,” wrote Tom Nolan. Record stores tended to file his albums in the rock section, even though, as Levinson, who played with Redbone for years, points out, that was “the one style of music he didn’t play.” Redbone believed American music had begun a steep decline when big bands started churning out what he described to one interviewer as “blatant sound for people to dance to.” He preferred sentiment, melody, subtlety, and romance—qualities of an earlier era that he brought forward with enough oddball visionary sensibility to get people to pay attention. At the same time, a sense of melancholy suffused his work: his version of “Shine on Harvest Moon” has an ambling sweetness, but he starts it off with an eerie, wobbly moan.

Redbone, who retired with health problems in 2015, was both a musical artist and a performance artist. His very identity was part of his creative output. Over his four-decade career, he released twelve studio albums and five live ones, acted and sang for film, TV, and commercials, and played thousands of shows across North America and Europe, introducing audiences to old melodies they might never have heard otherwise. Onstage, remembers cornetist Peter Ecklund, who accompanied Redbone in the 1970s and ’80s, he’d “create this alternate environment, this alternate universe, and you’d sort of live there for the duration of the show.” His refusal to reveal anything about himself other than what you might see onstage or hear on a record amplified that feeling. He invented himself from a Southern past he never experienced first-hand, and for years, no one seemed to know where he’d come from.

“Some people seem to believe that as soon as you perform on stage you lose your rights as a private citizen,” he complained. “They want to find out who I am, what I am, where I was born, how old I am—all this complete nonsense that belongs in a passport office.” It became de rigeur for journalists to try anyway, usually arriving at the contradiction that, as a 1991 Baltimore Sun headline put it, REDBONE DIGS INTO PAST FOR MUSIC, BUT WON’T LET YOU DIG INTO HIS PAST. What was his background? “That’s a memoir question. I don’t answer memoir questions.” Was it true, as the Toronto Star reported in 1986, that he was born Dickran Gobalian, in Cyprus, and came to Ontario in the 1960s? “I’ve read that,” he told another interviewer. “I don’t believe everything I read.” The mystique made for good publicity, but it wasn’t just a ploy. He was a celebrity protesting celebrity, with its mandates of self-disclosure and sensation. And he was getting out of the way so the music could come forward. “I’ve never considered myself the proper focus of attention,” he explained. “I’m just a vehicle.”

Due to his health, Leon Redbone can no longer be interviewed. In a way, he’s become a version of the old-time musicians he so admired, about whom little is known: You can only reach them through recordings, archival materials, and the accounts of other people. Longtime friends and band members tell me they knew never to ask about his past. Others say they were sworn to secrecy, and intend to keep the secrets. His own family members say they know little about his early life.

But Redbone himself doggedly chased the trails of his heroes. During down time on tours, he would head to county clerks’ offices and local libraries, hunting down information about the singer Emmett Miller. Miller, a white man who performed in blackface, emerged from the tangle of love and theft at the root of American popular culture—a history that fascinated Redbone, who took a term for a mixed-race person as his last name and performed songs written almost exclusively by other people. Miller played jaunty, ragged tunes and had what a 1927 reviewer called a “trick voice” that leapt from plaintive wails to high yodels. He recorded with some of the greatest jazz musicians of the 1920s—Gene Krupa, Eddie Lang, Tommy Dorsey—and, for Redbone, recalls the pianist Tom Roberts, Miller was one of the “Rosetta Stones for American music”: Study him enough, and all might be revealed. On the 1985 album Red to Blue, Redbone and Hank Williams Jr. did a comedy bit from an Emmett Miller recording before singing “Lovesick Blues,” a winking acknowledgment of the fact that Miller’s version of the song preceded Hank Senior’s. Redbone used Miller’s name as an alias when staying at hotels, receiving mail, or dodging phone calls: call up his old clamshell, and a voice would tell you to leave a message for Emmett. He considered writing Miller’s biography, and while that never happened, he amassed an archive of Miller material at his home in New Hope, Pennsylvania. He had another for Lee Morse, a slight, deep-voiced vaudeville songbird from rural Oregon who was reputed, at various points, to have come from Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Texas—supposed origins that worked in part to “authenticate” her blues singing.

In different ways, Morse and Miller both performed as people they weren’t, which may be part of what resonated with Redbone. But it was their artistry that earned his devotion. “His knowledge of these people was vast,” remembers dobro player Cindy Cashdollar, who sometimes accompanied Redbone in his research on tour, “but it was not only academic. It was personal.” For a while, at every show, he’d announce that if any family members of the 1920s clarinetist and contortionist Wilton Crawley were in the audience, they should see him “immediately.” No one did. But Redbone loved these artists’ work so much that their tunes alone weren’t enough. He wanted to know where they came from, and how they became who they were. It’s an understandable impulse.

Leon Redbone’s first guitar, or at least the first one anyone seems to remember seeing after he emerged on the Toronto folk scene in the late 1960s, was a Harmony Sovereign, transformed according to his vision. He painted the headstock to cover up the brand name and drew a meticulous pattern around the edges of the soundboard that, from the audience, resembled inlay. He used it to play old tunes from the 1920s and ’30s—country blues, ragtime—his voice shifting from molasses crooning to gravelly yowls. Dressed in the natty suits and ties of a Mississippi riverboat gambler, a Kentucky colonel, a dignified bluesman, or a Jimmie Rodgers–styled railroad brakeman with the right cap for the job, Redbone invited audiences into a tent show of American musical history where folks like Rodgers, Blind Blake, Emmett Miller, and Jelly Roll Morton could still draw crowds. His face was partially obscured by a hat and dark glasses. Sometimes he’d set a piece of fruit on the stool beside him: comically mute accompaniment. Redbone bought other guitars as his career took off, but his artistic ethos remained constant: Cover up some origins and conjure others. Craft an illusion and make it real. Bring the past into the present. Look at things slant. Do something beautiful, be careful about it, and keep your sunglasses on.

“The only thing that interests me,” said Redbone in a 1991 interview, “is history, reviewing the past and making something out of it.” He came of age in an era when plenty of musicians were looking backward. But where the folkies dusted off old songs like sacred artifacts, Redbone settled into the past like it was a familiar rocking chair, leisurely tuning his guitar with a sly growl of “Rise, Lazarus” or using it as a paddle to traverse an imaginary lazy river. Onstage, he took photographs of his audience, so that they—not he—became objects of attention. He blew bubbles, built a small table outfitted with an exploding device that he’d set off during “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” and engaged band members in banter lifted directly from the vaudeville era. Other jokes unfolded more quietly, with deadpan delivery—“This song has been around for over a hundred years,” the clarinetist Dan Levinson remembers him saying, “so you’ve had plenty of time to learn it. If you know the words, please hum along”—or small, masterful movements: a cock of the head, an exaggerated waggle of a hat brim. For years, Redbone would play a recording of the Hungarian opera singer Sári Barabás as his hands danced along, making shadows against a white cardboard screen.

Musically speaking, Redbone wasn’t as experimental as Tom Waits or Frank Zappa, but on the strength and strangeness of his persona, he was often compared to them. “He manifests himself as some kind of link between Robert Johnson and Richard Brautigan,” wrote Tom Nolan. Record stores tended to file his albums in the rock section, even though, as Levinson, who played with Redbone for years, points out, that was “the one style of music he didn’t play.” Redbone believed American music had begun a steep decline when big bands started churning out what he described to one interviewer as “blatant sound for people to dance to.” He preferred sentiment, melody, subtlety, and romance—qualities of an earlier era that he brought forward with enough oddball visionary sensibility to get people to pay attention. At the same time, a sense of melancholy suffused his work: his version of “Shine on Harvest Moon” has an ambling sweetness, but he starts it off with an eerie, wobbly moan.

Redbone, who retired with health problems in 2015, was both a musical artist and a performance artist. His very identity was part of his creative output. Over his four-decade career, he released twelve studio albums and five live ones, acted and sang for film, TV, and commercials, and played thousands of shows across North America and Europe, introducing audiences to old melodies they might never have heard otherwise. Onstage, remembers cornetist Peter Ecklund, who accompanied Redbone in the 1970s and ’80s, he’d “create this alternate environment, this alternate universe, and you’d sort of live there for the duration of the show.” His refusal to reveal anything about himself other than what you might see onstage or hear on a record amplified that feeling. He invented himself from a Southern past he never experienced first-hand, and for years, no one seemed to know where he’d come from.

“Some people seem to believe that as soon as you perform on stage you lose your rights as a private citizen,” he complained. “They want to find out who I am, what I am, where I was born, how old I am—all this complete nonsense that belongs in a passport office.” It became de rigeur for journalists to try anyway, usually arriving at the contradiction that, as a 1991 Baltimore Sun headline put it, REDBONE DIGS INTO PAST FOR MUSIC, BUT WON’T LET YOU DIG INTO HIS PAST. What was his background? “That’s a memoir question. I don’t answer memoir questions.” Was it true, as the Toronto Star reported in 1986, that he was born Dickran Gobalian, in Cyprus, and came to Ontario in the 1960s? “I’ve read that,” he told another interviewer. “I don’t believe everything I read.” The mystique made for good publicity, but it wasn’t just a ploy. He was a celebrity protesting celebrity, with its mandates of self-disclosure and sensation. And he was getting out of the way so the music could come forward. “I’ve never considered myself the proper focus of attention,” he explained. “I’m just a vehicle.”

Due to his health, Leon Redbone can no longer be interviewed. In a way, he’s become a version of the old-time musicians he so admired, about whom little is known: You can only reach them through recordings, archival materials, and the accounts of other people. Longtime friends and band members tell me they knew never to ask about his past. Others say they were sworn to secrecy, and intend to keep the secrets. His own family members say they know little about his early life.

But Redbone himself doggedly chased the trails of his heroes. During down time on tours, he would head to county clerks’ offices and local libraries, hunting down information about the singer Emmett Miller. Miller, a white man who performed in blackface, emerged from the tangle of love and theft at the root of American popular culture—a history that fascinated Redbone, who took a term for a mixed-race person as his last name and performed songs written almost exclusively by other people. Miller played jaunty, ragged tunes and had what a 1927 reviewer called a “trick voice” that leapt from plaintive wails to high yodels. He recorded with some of the greatest jazz musicians of the 1920s—Gene Krupa, Eddie Lang, Tommy Dorsey—and, for Redbone, recalls the pianist Tom Roberts, Miller was one of the “Rosetta Stones for American music”: Study him enough, and all might be revealed. On the 1985 album Red to Blue, Redbone and Hank Williams Jr. did a comedy bit from an Emmett Miller recording before singing “Lovesick Blues,” a winking acknowledgment of the fact that Miller’s version of the song preceded Hank Senior’s. Redbone used Miller’s name as an alias when staying at hotels, receiving mail, or dodging phone calls: call up his old clamshell, and a voice would tell you to leave a message for Emmett. He considered writing Miller’s biography, and while that never happened, he amassed an archive of Miller material at his home in New Hope, Pennsylvania. He had another for Lee Morse, a slight, deep-voiced vaudeville songbird from rural Oregon who was reputed, at various points, to have come from Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Texas—supposed origins that worked in part to “authenticate” her blues singing.

In different ways, Morse and Miller both performed as people they weren’t, which may be part of what resonated with Redbone. But it was their artistry that earned his devotion. “His knowledge of these people was vast,” remembers dobro player Cindy Cashdollar, who sometimes accompanied Redbone in his research on tour, “but it was not only academic. It was personal.” For a while, at every show, he’d announce that if any family members of the 1920s clarinetist and contortionist Wilton Crawley were in the audience, they should see him “immediately.” No one did. But Redbone loved these artists’ work so much that their tunes alone weren’t enough. He wanted to know where they came from, and how they became who they were. It’s an understandable impulse.

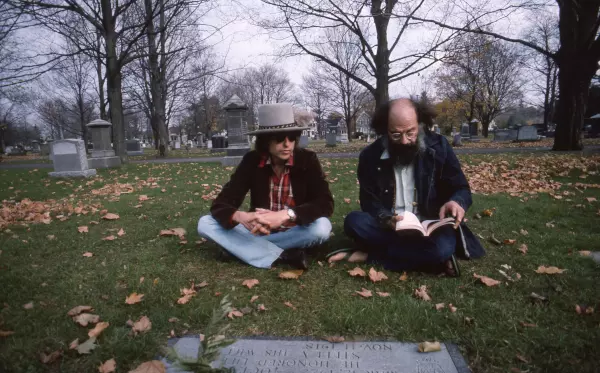

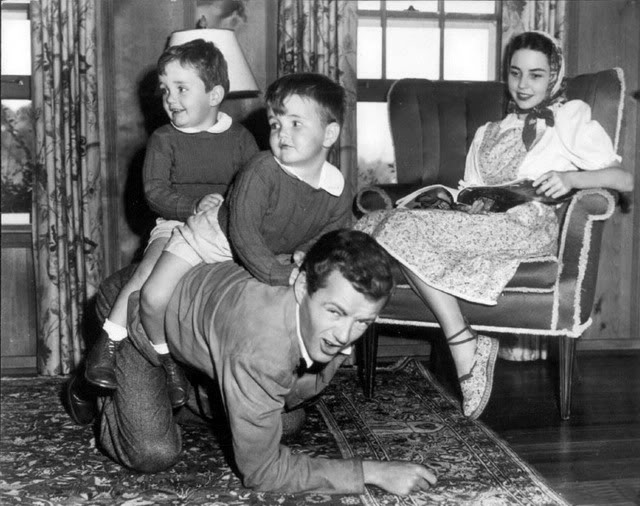

Leon Redbone and Bob Dylan at the Mariposa Folk Festival, 1972. Copyright Arthur Usherson

Redbone showed up in Toronto in the late 1960s—from where, no one seemed certain. He was from Shreveport, Louisiana, people said, or from New Orleans, or maybe from Cleveland, dodging the draft. One musician detected a British lilt to his phrasing, but by the late 1970s, an interviewer heard “a New England accent” in Redbone’s “low, nasal speaking voice.” Redbone later claimed to have been born in Bombay, the love child of Jenny Lind and Niccolo Paganini; in Manhattan, the day of the 1929 stock market crash; and in Memphis, Tennessee. When an interviewer asked where in Memphis he’d gone to school, he changed the subject.

In Toronto, he was a regular at Fiddler’s Green, a folk club that rented space a couple nights a week in a run-down house owned by the YMCA, and his gigs there landed him a spot at Mariposa Folk Festival. But his earliest appearances may have been at the Pornographic Onion, a coffeehouse at Ryerson University that hosted hootenannies sponsored by the Toronto Folklore Center in the 1960s. Shelley Posen, who used to emcee those shows, remembers that whenever someone gave Redbone a lift home, he’d ask to be let out at an intersection in Forest Hill where there was a large apartment building. No one knew if he lived there. After exiting the car, he stood on the sidewalk “and waited there, waving goodbye, until the car disappeared from view. If the car didn’t move, he didn’t move.” Once, says promoter Richard Flohil, someone did see Redbone enter an apartment building, only to walk back out a few moments later, climb into a cab, and head off. Another time, recalls musician Michael Cooney, someone dropped Redbone at a hotel, and “he went in the front door and came out the side door and went into the subway.”

In those days, the only way to reach Redbone was by phoning the pool hall by the subway stop at the corner of Bloor and Yonge Street and asking for Mr. Grunt, though the guys there also knew him as Sonny. Redbone was something of a shark, stalking the billiard table and sinking balls with graceful ferocity. A 1973 profile describes the way that, “Right foot back, pool cue resting emphatically on thumb and knuckle, he double-banks a red into the side pocket and prepares to make an eighty degree cut black.” Then he proclaims, “‘I don’t have a past. The past begins tomorrow.’” Another bank shot.

The bio he submitted for the 1972 Mariposa Folk Festival program reads as follows: “I was born in Shreveport, La., in 1910, and my real name is James Hokum. I wear dark glasses to remind me of the time I spent leading Blind Blake throughout the south, and I now live in Canada as a result of the incident in Philadelphia.” The editors noted that, when asked for a photograph, Redbone had sent them a picture of Bob Dylan, but they didn’t print it. The joke proved prescient: Dylan showed up at the festival unannounced, searching for Leon Redbone. John Prine describes the scene with delight in the new documentary short Please Don’t Talk about Me When I’m Gone, produced by Riddle Films: there was Redbone, followed by Dylan and his wife, followed by hordes of adoring fans. The festival took place on an island, accessible by ferry, but at the end of the day, Dylan, Gordon Lightfoot, and Redbone sailed away on a private boat.

A few months later, Atlantic reportedly made overtures to sign Redbone, and Jerry Wexler hoped Dylan might help produce him. When that fell through, Dylan invited Redbone to meet him at a hotel in New York City. No one seems quite sure what they talked about. But in a 1974 Rolling Stone article, Dylan is quoted as saying that, if he had his own record label, he’d sign Redbone: “‘Leon interests me,’ he said. ‘I’ve heard he’s anywhere from 25 to 60, I’ve been this close’”—Dylan held his hands out, a foot and a half apart—“‘and I can’t tell. But you gotta see him.’”

Warner Bros. signed Redbone and released his first album, On the Track, the following year. When he played “Shine on Harvest Moon” and “Walking Stick” on Saturday Night Live a few months later, sales jumped from fifteen thousand to one hundred ninety thousand. SNL had him back several times, and his career seemed made. Redbone had been reluctant about performing on television, but his wife and manager, Beryl Handler, knew it was too good an opportunity to pass up. Her role in his career, their friends say, is hard to overstate. They met when she was a student at the University of Buffalo, helping run the 1972 Buffalo Festival, and while he is a cautious introvert, she has had the pragmatism and drive to bring his talents to the public. They have two daughters, though he has avoided speaking about them: when a radio interviewer mentioned having seen Redbone with his family in New York, he countered that they might’ve been “a rental for the day.”

Handler secured Redbone’s television gigs, negotiated contracts for his commercial work (including ads for Budweiser and British Rail), and licensed his songs, which have been used in several films as well as two ballets choreographed by Eliot Feld. (In one, Mr. XYZ,Baryshnikov plays a sort of weary vaudevillian, complete with hat and cane.) Handler also coproduced most of Redbone’s records. Today, she and their daughter Ashley, who manages a recording studio in New Haven, are working to digitize troves of old tape, some of which will almost certainly be released in the years to come. “I’m in it for the banter,” says Ashley Redbone. She’s looking for the crackle and closeness of liveness, the sense of Redbone as a person—wry, playful, trying things out and seeing what worked.

In the era of music Redbone loved most, bands would record all together in a room. But in the studio, he and his producers usually had musicians lay down separate tracks, which they’d piece together later to achieve the desired effect. Handler compares the process to collage—they weren’t reenacting the past, but using present-day tools to evoke it. Redbone described himself, with deflecting modesty, as a tinkerer, but some of his friends prefer “inventor.” Dave Siglin, who with his wife Linda ran the Ann Arbor folk venue the Ark, encouraged Redbone to take out a patent after he attached wheels to a suitcase filled with gear to make it easier to carry. No one else could possibly want it, Redbone insisted, though someone else did patent the rolling suitcase, and doubtless made a fortune. Siglin also remembers Redbone stalking a street-cleaning machine, waiting for a metal tine to fall from its brush so that—under cover of a handkerchief—he could thread it through the strings of his guitar and make sounds like a steel drum. At his family’s home, Redbone built a deck and an outdoor oven, made a mosaic on the bathroom floor, gardened, welded, wired, and fixed plumbing. He had a darkroom in the basement where he’d develop the photographs he took. He drew charming sketches, some of which adorned his albums, or the cassette tapes he’d make for friends. He liked to pick things up and figure out how they worked. It’s how he learned to play not just guitar, but also piano, harmonica, banjo, mandolin, and zither.

Leon Redbone was both self-made and self-taught. In the late 1970s, he told Guitar Playerthat he was not one of those “people who can actually play things note for note”—instead, he went by his ear, doing what best suited him and his voice. This irked some purists: Dave Van Ronk grumbled that even with the legendary Joe Venuti in the studio, Redbone had recorded the wrong chords to “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” Yet, points out the pianist Terry Waldo, musicians across the folk tradition have always taken what they heard and made it their own—Redbone “was authentic in that sense.”

He went by feel onstage as well, eschewing set lists and never rehearsing with the band. But his musicians knew his repertoire, and when he’d start playing a song, they were ready to join in. Occasionally they made plans in advance. Typically, when audiences requested “Seduced,” a song whose pop success Redbone seemed almost to resent, he’d reply, “Oh, behave yourselves,” and go right on playing the songs he preferred. Once, at a show in New Jersey, he told the band that when the inevitable request came, pianist Stanley Schwartz should pretend to count in “Seduced,” and then they’d all play different tunes at once—different keys, different tempos. The request came. “Stanley, count us in,” Dan Levinson remembers Redbone saying. The discord went on “for about ten to fifteen seconds and then he said, ‘Wait a minute, hold it, hold it. Let’s try that again.’ We did the whole thing again. ‘You know what, maybe we should play another song.’” No one requested “Seduced” for the rest of the night.

More - much more here:

https://www.oxfordamerican.org/magazine/item/1703-vessel-of-antiquity

Redbone showed up in Toronto in the late 1960s—from where, no one seemed certain. He was from Shreveport, Louisiana, people said, or from New Orleans, or maybe from Cleveland, dodging the draft. One musician detected a British lilt to his phrasing, but by the late 1970s, an interviewer heard “a New England accent” in Redbone’s “low, nasal speaking voice.” Redbone later claimed to have been born in Bombay, the love child of Jenny Lind and Niccolo Paganini; in Manhattan, the day of the 1929 stock market crash; and in Memphis, Tennessee. When an interviewer asked where in Memphis he’d gone to school, he changed the subject.

In Toronto, he was a regular at Fiddler’s Green, a folk club that rented space a couple nights a week in a run-down house owned by the YMCA, and his gigs there landed him a spot at Mariposa Folk Festival. But his earliest appearances may have been at the Pornographic Onion, a coffeehouse at Ryerson University that hosted hootenannies sponsored by the Toronto Folklore Center in the 1960s. Shelley Posen, who used to emcee those shows, remembers that whenever someone gave Redbone a lift home, he’d ask to be let out at an intersection in Forest Hill where there was a large apartment building. No one knew if he lived there. After exiting the car, he stood on the sidewalk “and waited there, waving goodbye, until the car disappeared from view. If the car didn’t move, he didn’t move.” Once, says promoter Richard Flohil, someone did see Redbone enter an apartment building, only to walk back out a few moments later, climb into a cab, and head off. Another time, recalls musician Michael Cooney, someone dropped Redbone at a hotel, and “he went in the front door and came out the side door and went into the subway.”

In those days, the only way to reach Redbone was by phoning the pool hall by the subway stop at the corner of Bloor and Yonge Street and asking for Mr. Grunt, though the guys there also knew him as Sonny. Redbone was something of a shark, stalking the billiard table and sinking balls with graceful ferocity. A 1973 profile describes the way that, “Right foot back, pool cue resting emphatically on thumb and knuckle, he double-banks a red into the side pocket and prepares to make an eighty degree cut black.” Then he proclaims, “‘I don’t have a past. The past begins tomorrow.’” Another bank shot.

The bio he submitted for the 1972 Mariposa Folk Festival program reads as follows: “I was born in Shreveport, La., in 1910, and my real name is James Hokum. I wear dark glasses to remind me of the time I spent leading Blind Blake throughout the south, and I now live in Canada as a result of the incident in Philadelphia.” The editors noted that, when asked for a photograph, Redbone had sent them a picture of Bob Dylan, but they didn’t print it. The joke proved prescient: Dylan showed up at the festival unannounced, searching for Leon Redbone. John Prine describes the scene with delight in the new documentary short Please Don’t Talk about Me When I’m Gone, produced by Riddle Films: there was Redbone, followed by Dylan and his wife, followed by hordes of adoring fans. The festival took place on an island, accessible by ferry, but at the end of the day, Dylan, Gordon Lightfoot, and Redbone sailed away on a private boat.

A few months later, Atlantic reportedly made overtures to sign Redbone, and Jerry Wexler hoped Dylan might help produce him. When that fell through, Dylan invited Redbone to meet him at a hotel in New York City. No one seems quite sure what they talked about. But in a 1974 Rolling Stone article, Dylan is quoted as saying that, if he had his own record label, he’d sign Redbone: “‘Leon interests me,’ he said. ‘I’ve heard he’s anywhere from 25 to 60, I’ve been this close’”—Dylan held his hands out, a foot and a half apart—“‘and I can’t tell. But you gotta see him.’”

Warner Bros. signed Redbone and released his first album, On the Track, the following year. When he played “Shine on Harvest Moon” and “Walking Stick” on Saturday Night Live a few months later, sales jumped from fifteen thousand to one hundred ninety thousand. SNL had him back several times, and his career seemed made. Redbone had been reluctant about performing on television, but his wife and manager, Beryl Handler, knew it was too good an opportunity to pass up. Her role in his career, their friends say, is hard to overstate. They met when she was a student at the University of Buffalo, helping run the 1972 Buffalo Festival, and while he is a cautious introvert, she has had the pragmatism and drive to bring his talents to the public. They have two daughters, though he has avoided speaking about them: when a radio interviewer mentioned having seen Redbone with his family in New York, he countered that they might’ve been “a rental for the day.”

Handler secured Redbone’s television gigs, negotiated contracts for his commercial work (including ads for Budweiser and British Rail), and licensed his songs, which have been used in several films as well as two ballets choreographed by Eliot Feld. (In one, Mr. XYZ,Baryshnikov plays a sort of weary vaudevillian, complete with hat and cane.) Handler also coproduced most of Redbone’s records. Today, she and their daughter Ashley, who manages a recording studio in New Haven, are working to digitize troves of old tape, some of which will almost certainly be released in the years to come. “I’m in it for the banter,” says Ashley Redbone. She’s looking for the crackle and closeness of liveness, the sense of Redbone as a person—wry, playful, trying things out and seeing what worked.

In the era of music Redbone loved most, bands would record all together in a room. But in the studio, he and his producers usually had musicians lay down separate tracks, which they’d piece together later to achieve the desired effect. Handler compares the process to collage—they weren’t reenacting the past, but using present-day tools to evoke it. Redbone described himself, with deflecting modesty, as a tinkerer, but some of his friends prefer “inventor.” Dave Siglin, who with his wife Linda ran the Ann Arbor folk venue the Ark, encouraged Redbone to take out a patent after he attached wheels to a suitcase filled with gear to make it easier to carry. No one else could possibly want it, Redbone insisted, though someone else did patent the rolling suitcase, and doubtless made a fortune. Siglin also remembers Redbone stalking a street-cleaning machine, waiting for a metal tine to fall from its brush so that—under cover of a handkerchief—he could thread it through the strings of his guitar and make sounds like a steel drum. At his family’s home, Redbone built a deck and an outdoor oven, made a mosaic on the bathroom floor, gardened, welded, wired, and fixed plumbing. He had a darkroom in the basement where he’d develop the photographs he took. He drew charming sketches, some of which adorned his albums, or the cassette tapes he’d make for friends. He liked to pick things up and figure out how they worked. It’s how he learned to play not just guitar, but also piano, harmonica, banjo, mandolin, and zither.

Leon Redbone was both self-made and self-taught. In the late 1970s, he told Guitar Playerthat he was not one of those “people who can actually play things note for note”—instead, he went by his ear, doing what best suited him and his voice. This irked some purists: Dave Van Ronk grumbled that even with the legendary Joe Venuti in the studio, Redbone had recorded the wrong chords to “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” Yet, points out the pianist Terry Waldo, musicians across the folk tradition have always taken what they heard and made it their own—Redbone “was authentic in that sense.”

He went by feel onstage as well, eschewing set lists and never rehearsing with the band. But his musicians knew his repertoire, and when he’d start playing a song, they were ready to join in. Occasionally they made plans in advance. Typically, when audiences requested “Seduced,” a song whose pop success Redbone seemed almost to resent, he’d reply, “Oh, behave yourselves,” and go right on playing the songs he preferred. Once, at a show in New Jersey, he told the band that when the inevitable request came, pianist Stanley Schwartz should pretend to count in “Seduced,” and then they’d all play different tunes at once—different keys, different tempos. The request came. “Stanley, count us in,” Dan Levinson remembers Redbone saying. The discord went on “for about ten to fifteen seconds and then he said, ‘Wait a minute, hold it, hold it. Let’s try that again.’ We did the whole thing again. ‘You know what, maybe we should play another song.’” No one requested “Seduced” for the rest of the night.

More - much more here:

https://www.oxfordamerican.org/magazine/item/1703-vessel-of-antiquity

![[​IMG]](https://i.postimg.cc/521SkWJw/61656020-2262244307375435-5608877188611833856-o.jpg)