At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

Just My Imagination

Need Your Love So Bad

Da Elderly: -

Once An Angel

You've Got A Friend

The Elderly Brothers: -

When Will I Be Loved

Yes I Will

Let It Be Me

Back "by popular request" (haha!) The Elderly Brothers finished off a night packed with players, including a new female duo who played some funky tunes and nonagenarian Don who wowed the crowd with a rendition of Around The World. It was so busy that we ran out of time and had to save our to-be-final song I Saw Her Standing There for the after-show acoustic jam. The place was just about full all night with a very supportive audience. The acoustic jam ran right through until closing time with everyone joining in. After time was called a couple from Liverpool who had clearly enjoyed themselves stood up and thanked everyone for a great night - and so it was!

Thursday 31 August 2017

Wednesday 30 August 2017

Tuesday 29 August 2017

Sunday 27 August 2017

Saturday 26 August 2017

Friday 25 August 2017

Dead Poets Society #47 Stanley Kunitz: End of Summer

End of Summer by Stanley Kunitz

An agitation of the air,

A perturbation of the light

Admonished me the unloved year

Would turn on its hinge that night.

I stood in the disenchanted field

Amid the stubble and the stones,

Amazed, while a small worm lisped to me

The song of my marrow-bones.

Blue poured into summer blue,

A hawk broke from his cloudless tower,

The roof of the silo blazed, and I knew

That part of my life was over.

Already the iron door of the north

Clangs open: birds, leaves, snows

Order their populations forth,

And a cruel wind blows.

Thursday 24 August 2017

Wednesday 23 August 2017

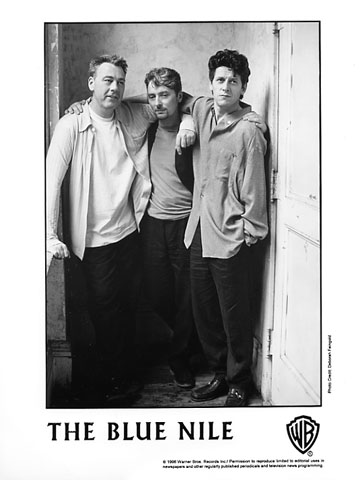

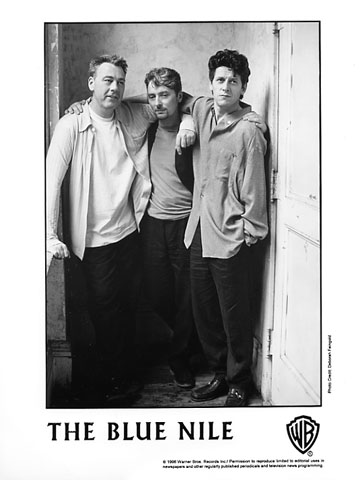

In Search of The Blue Nile - Ken Sweeney's radio documentary

In Search of The Blue Nile

Ken Sweeney on his radio documentary

Paul Trainer

Talk of the Town

16 April 2017

When Irish journalist Ken Sweeney visited Glasgow for the first time, it was a pilgrimage to a place that had existed in his imagination ever since he first heard the music of The Blue Nile. It was also the start of a labour of love as he set out to tell the story of the band in their own words. The result was a delicately crafted radio documentary that was broadcast on RTE in Ireland and found an audience around the world.

Peter Gabriel, Ryan Adams and The 1975 were among those who voiced praise for the programme. John Douglas, husband of Eddie Reader and member of The Trashcan Sinatras describes In Search of The Blue Nile as “beautiful, respectful, probing and informative”.

The attention has led to BBC Scotland scheduling an updated version of In Search of The Blue Nile for Easter Monday at 4pm. Glasgowist spoke to Ken after the first broadcast and caught up with him recently to find out more.

You were back in Glasgow in March, was there more work to do on the documentary before it was ready for a Scottish audience?

I was back over in Glasgow to re-voice some of the doc. It was the most amazing sunny weekend, Glasgow seemed a different city, everybody seemed to be out in the park.

I spent a whole day with [The Blue Nile keyboard player] PJ Moore and at one point we were back up at the spot at Kelvingrove where we created the picture taken by John G Moore – where I had interviewed him in the rain last November. It was so sunny, there were people sun bathing beside us on the steps.

When I was doing the doc originally I used to love getting a 6:30am plane over from Dublin and getting onto the streets of Glasgow before 8am in the morning.

I would go from one end of the city to the other and eventually I would eat in an Italian restaurant called Amalfi – at 148 West Nile Street. They do great ravioli.

That weekend you were here, the BBC 6 Music festival was on and Paul Buchanan from The Blue Nile was speaking at one of the events, what was that like?

Paul took me along to that. I met him at the hotel where his manager was staying and we took a cab over. He’s incredibly cool Paul, wearing this leather jacket, and looking so slim.

We were in the backstage area of The Tramway venue. All those BBC 6 presenters were knocking around.

Mark Radcliffe seemed to be a big fan and was talking to Paul for a while and asking about his solo album. So was Gideon Coe who chaired the talk.

I bumped into Edwyn Collins, who I knew from my days recording on Setanta Records and it turned out Paul was a great pal of Edwyn’s wife Grace, I think they might been in college together.

There was a lot of excitement about Paul’s new album because Paul said it was two thirds complete.

Are you pleased there will now be a Scottish broadcast of the documentary?

I’ve been getting calls this week from friends in Scotland who have been hearing trailers for this on the radio.

I’m delighted BBC Scotland are airing it in such a good slot, 4pm on a Bank Holiday.

You can have the doc shared on social media but there is a huge, older audience out there you can’t get too. I suspect there’s a lot of Blue Nile fans who don’t know anything about the documentary and will be hearing it for the first time.

Something I really want to do with my doc was put Stuart Adamson of Big Country back into the Blue Nile story, Stuart Adamson is revered in Ireland.

Edge of U2 based his guitar sound on what Stuart was doing in The Skids but even big Blue Nile fans, didn’t seem to know the part Stuart played in bringing The Blue Nile to the attention of Virgin Records, through his pal Ronnie Gurr, who was an A&R man with Virgin. It’s certainly makes for a very dramatic part of the story.

Was it easy to get the backing to put the documentary together? How sure were you that it would find an audience?

The previous radio doc I produced was about a cabbie who drove Michael Jackson around Ireland when he lived here. It was my first documentary, and, to my shock, won an Irish radio award. But I wasn’t really a fan of Michael Jackson. I waited a few years before doing another.

This time I wanted to do something on a musician or band I loved. There were a few people who advised me I was wasting my time making a documentary on The Blue Nile in 2017.

They said I was right about Michael Jackson but The Blue Nile? They just laughed and said this band didn’t have any hits when they were together. So why would anyone be interested now… One industry guy went further and said that he doubted there was any kind of audience for The Blue Nile in 2017.

How wrong they were… from the moment someone on the Blue Nile Facebook saw a radio listing in the RTE Guide, it just took off. I was a bit surprised when RTE suggested putting it online before broadcast. There were some difficulties accessing it from the RTE Player, then a Blue Nile fan off the facebook, Kieran McCarthy, suggested a Soundcloud. That went up and it clocked up thousands of plays.

First in Ireland then Nicola Meighan tweeted a link which sent it across Scotland and the UK. Then it started getting picked up in America.

People who liked the doc, would tweet it, and then tweet it again.

My Twitter handle would sometimes get used and I’d get up in the morning and see all these messages from people playing the documentary. I got up one morning and this guy was DMing me about The Blue Nile, we’d started to chat before I realised it was Ryan Adams, the American singer. I was following him already on twitter, he followed me and we were having this conversation.

The people tweeting it were so diverse, along with Peter Gabriel who posted it on his social media accounts, there was the artistic director of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, fans in the Middle East, Japanese tweets I can’t read.

This programme has reached a much bigger audience than my Michael Jackson documentary. It’s just woken up a sleeping army of Blue Nile fans worldwide. There definitely is a market for this band in 2017.

With Paul having a new record ready to go, the doc might seem as if it was planned. It wasn’t …. I just had a mad idea to jump on a plane and start this last November.

The Blue Nile had a great connection to the late journalist George Byrne. They were really shocked to hear of his death two years ago and we all liked the idea that RTE would make this doc about The Blue Nile dedicated to George.

So, from that discussion last month for the 6 Music Festival, there was a bit of confusion. Paul said he had an album that was almost finished, which I presumed to be his solo material, but it was picked up on Twitter as indications that there was a new Blue Nile album in the works. We’ve asked you this before, but we’ll ask again to clarify – will The Blue Nile work together again?

Paul Buchanan and PJ Moore haven’t spoken in several years. In a weird way they were speaking to each other through my documentary.

It’s really nice to hear Paul praising PJ in the programme saying “no one will ever play a Roland the way PJ did in the studio etc. PJ also seemed to have better idea of what was achievable; Paul quotes him saying that the second record couldn’t be done in the short time frame in which the record company wanted it delivered.

On the subject of a reunion. Paul quotes PJ in the documentary, saying that “they made each other too nervous in the studio.” He agrees.

Paul Buchanan’s last album got rave reviews, I think it was as good as any Blue Nile record, maybe better than the last two (Peace At Last and High).*

This new record from Paul is very different in that I believe it has a band sound. There was some confusion when BBC 6 Music said a Blue Nile record was planned after Paul spoke at that panel in Glasgow.

I have no information about whether it’s a going to be released as a Paul Buchanan album or under the Blue Nile title. There’s a whole discussion you could have about it, if PJ and Robert don’t want to perform as The Blue Nile anymore, and Paul wants to, could The Blue Nile name be used?

It doesn’t for a moment diminish PJ or Robert’s contribution in the past. I can remember seeing Prefab Sprout playing in Dublin without key members, and Jeff Lynne tours as ELO. I suppose we will find out in time. I don’t know either way.

What impact did The Blue Nile have in Ireland?

People in Scotland seemed surprised that Irish radio commissioned my documentary. I’m delighted really because The Blue Nile always had a special relationship with Ireland.

PJ Moore summed up The Blue Nile in Ireland to me recently. He said that unlike the London music business where The Blue Nile hadn’t worked… Ireland was different, PJ said “The cogs turned for The Blue Nile in Ireland”.

Radio guys, like Mark Cagney played their music on late night radio, mainstream DJ’s like Gerry Ryan, heard it and liked it and started playing it on daytime radio.

If you look on YouTube you can find clips of Paul bring interviewed on Breakfast TV in Ireland by Mark Cagney who as a late night DJ was one of the first people to play The Blue Nile.

PJ says The Blue Nile were embraced by everybody in Dublin who understood what the Blue Nile were trying to do. The band moved there for a while.

Paul talks about the band deciding to leave Dublin but the night before they left, they had a drive around Stephen’s Green, and changed their mind and stayed in Dublin for another six months.

One of the sweetest messages I got talking about The Blue Nile on Irish radio was from a guy who rang in to say he had been a young barman in a pub on Baggot Street. .

He remembered these three unassuming Scottish guys chatting to him one night at the bar, asking him about himself, his life and his family, and when he asked them about themselves, they told him they were in a band he would never have heard of…

But years later, he now knew all about The Blue Nile and their records and remembered that night in the bar.

Was there anything you left out of the documentary?

There were other people, I interviewed like RTE’s Cathal Murray, Dave Fanning, Dan Hegarty and the TV producer Dave Heffernan I interviewed but there just wasn’t the room to include, and I wasn’t going lose Paul or PJ talking about the recording of Hats to include them.

The Irish actor Liam Cunningham from Game Of Thrones, I interviewed and I couldn’t squeeze in either. He’s so evangelical about The Blue Nile but had never met them. I sent the audio of Liam’s interview to Paul, and Paul rang him up in Dublin to thank him. Which must have been an incredible call for Liam to get.

If I’d had more time, I’d love to have got Billy Sloan, the Scottish journalist and presenter into the doc.

But I ran out of time, on my last day, he was the opposite end of Glasgow. I wouldn’t have made my plane but he provided me with some valuable insight on the band, and was a huge supporter of The Blue Nile.

The documentary was recorded in Dublin and Glasgow, I’d like to say thanks to Frank Kearns at Salt Studios for his help putting it together.

Can we expect more documentaries from you Ken? Are there other band stories you would like to tell?

I’ve had some Irish bands contact me since, asking me would I make a similar radio documentary about them. But my heart wouldn’t be in it… and the story of The Blue Nile can’t be matched.

They were in operating at this crazy time when record companies were selling double – as people bought their entire vinyl collection again on CD.

You can see why there was pressure on The Blue Nile to come up with a second album and a third album.

In Search of The Blue Nile will be broadcast on BBC Scotland at 4pm on 17th April.

When Irish journalist Ken Sweeney visited Glasgow for the first time, it was a pilgrimage to a place that had existed in his imagination ever since he first heard the music of The Blue Nile. It was also the start of a labour of love as he set out to tell the story of the band in their own words. The result was a delicately crafted radio documentary that was broadcast on RTE in Ireland and found an audience around the world.

Peter Gabriel, Ryan Adams and The 1975 were among those who voiced praise for the programme. John Douglas, husband of Eddie Reader and member of The Trashcan Sinatras describes In Search of The Blue Nile as “beautiful, respectful, probing and informative”.

The attention has led to BBC Scotland scheduling an updated version of In Search of The Blue Nile for Easter Monday at 4pm. Glasgowist spoke to Ken after the first broadcast and caught up with him recently to find out more.

You were back in Glasgow in March, was there more work to do on the documentary before it was ready for a Scottish audience?

I was back over in Glasgow to re-voice some of the doc. It was the most amazing sunny weekend, Glasgow seemed a different city, everybody seemed to be out in the park.

I spent a whole day with [The Blue Nile keyboard player] PJ Moore and at one point we were back up at the spot at Kelvingrove where we created the picture taken by John G Moore – where I had interviewed him in the rain last November. It was so sunny, there were people sun bathing beside us on the steps.

When I was doing the doc originally I used to love getting a 6:30am plane over from Dublin and getting onto the streets of Glasgow before 8am in the morning.

I would go from one end of the city to the other and eventually I would eat in an Italian restaurant called Amalfi – at 148 West Nile Street. They do great ravioli.

That weekend you were here, the BBC 6 Music festival was on and Paul Buchanan from The Blue Nile was speaking at one of the events, what was that like?

Paul took me along to that. I met him at the hotel where his manager was staying and we took a cab over. He’s incredibly cool Paul, wearing this leather jacket, and looking so slim.

We were in the backstage area of The Tramway venue. All those BBC 6 presenters were knocking around.

Mark Radcliffe seemed to be a big fan and was talking to Paul for a while and asking about his solo album. So was Gideon Coe who chaired the talk.

I bumped into Edwyn Collins, who I knew from my days recording on Setanta Records and it turned out Paul was a great pal of Edwyn’s wife Grace, I think they might been in college together.

There was a lot of excitement about Paul’s new album because Paul said it was two thirds complete.

Are you pleased there will now be a Scottish broadcast of the documentary?

I’ve been getting calls this week from friends in Scotland who have been hearing trailers for this on the radio.

I’m delighted BBC Scotland are airing it in such a good slot, 4pm on a Bank Holiday.

You can have the doc shared on social media but there is a huge, older audience out there you can’t get too. I suspect there’s a lot of Blue Nile fans who don’t know anything about the documentary and will be hearing it for the first time.

Something I really want to do with my doc was put Stuart Adamson of Big Country back into the Blue Nile story, Stuart Adamson is revered in Ireland.

Edge of U2 based his guitar sound on what Stuart was doing in The Skids but even big Blue Nile fans, didn’t seem to know the part Stuart played in bringing The Blue Nile to the attention of Virgin Records, through his pal Ronnie Gurr, who was an A&R man with Virgin. It’s certainly makes for a very dramatic part of the story.

Was it easy to get the backing to put the documentary together? How sure were you that it would find an audience?

The previous radio doc I produced was about a cabbie who drove Michael Jackson around Ireland when he lived here. It was my first documentary, and, to my shock, won an Irish radio award. But I wasn’t really a fan of Michael Jackson. I waited a few years before doing another.

This time I wanted to do something on a musician or band I loved. There were a few people who advised me I was wasting my time making a documentary on The Blue Nile in 2017.

They said I was right about Michael Jackson but The Blue Nile? They just laughed and said this band didn’t have any hits when they were together. So why would anyone be interested now… One industry guy went further and said that he doubted there was any kind of audience for The Blue Nile in 2017.

How wrong they were… from the moment someone on the Blue Nile Facebook saw a radio listing in the RTE Guide, it just took off. I was a bit surprised when RTE suggested putting it online before broadcast. There were some difficulties accessing it from the RTE Player, then a Blue Nile fan off the facebook, Kieran McCarthy, suggested a Soundcloud. That went up and it clocked up thousands of plays.

First in Ireland then Nicola Meighan tweeted a link which sent it across Scotland and the UK. Then it started getting picked up in America.

People who liked the doc, would tweet it, and then tweet it again.

My Twitter handle would sometimes get used and I’d get up in the morning and see all these messages from people playing the documentary. I got up one morning and this guy was DMing me about The Blue Nile, we’d started to chat before I realised it was Ryan Adams, the American singer. I was following him already on twitter, he followed me and we were having this conversation.

The people tweeting it were so diverse, along with Peter Gabriel who posted it on his social media accounts, there was the artistic director of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, fans in the Middle East, Japanese tweets I can’t read.

This programme has reached a much bigger audience than my Michael Jackson documentary. It’s just woken up a sleeping army of Blue Nile fans worldwide. There definitely is a market for this band in 2017.

With Paul having a new record ready to go, the doc might seem as if it was planned. It wasn’t …. I just had a mad idea to jump on a plane and start this last November.

The Blue Nile had a great connection to the late journalist George Byrne. They were really shocked to hear of his death two years ago and we all liked the idea that RTE would make this doc about The Blue Nile dedicated to George.

So, from that discussion last month for the 6 Music Festival, there was a bit of confusion. Paul said he had an album that was almost finished, which I presumed to be his solo material, but it was picked up on Twitter as indications that there was a new Blue Nile album in the works. We’ve asked you this before, but we’ll ask again to clarify – will The Blue Nile work together again?

Paul Buchanan and PJ Moore haven’t spoken in several years. In a weird way they were speaking to each other through my documentary.

It’s really nice to hear Paul praising PJ in the programme saying “no one will ever play a Roland the way PJ did in the studio etc. PJ also seemed to have better idea of what was achievable; Paul quotes him saying that the second record couldn’t be done in the short time frame in which the record company wanted it delivered.

On the subject of a reunion. Paul quotes PJ in the documentary, saying that “they made each other too nervous in the studio.” He agrees.

Paul Buchanan’s last album got rave reviews, I think it was as good as any Blue Nile record, maybe better than the last two (Peace At Last and High).*

This new record from Paul is very different in that I believe it has a band sound. There was some confusion when BBC 6 Music said a Blue Nile record was planned after Paul spoke at that panel in Glasgow.

I have no information about whether it’s a going to be released as a Paul Buchanan album or under the Blue Nile title. There’s a whole discussion you could have about it, if PJ and Robert don’t want to perform as The Blue Nile anymore, and Paul wants to, could The Blue Nile name be used?

It doesn’t for a moment diminish PJ or Robert’s contribution in the past. I can remember seeing Prefab Sprout playing in Dublin without key members, and Jeff Lynne tours as ELO. I suppose we will find out in time. I don’t know either way.

What impact did The Blue Nile have in Ireland?

People in Scotland seemed surprised that Irish radio commissioned my documentary. I’m delighted really because The Blue Nile always had a special relationship with Ireland.

PJ Moore summed up The Blue Nile in Ireland to me recently. He said that unlike the London music business where The Blue Nile hadn’t worked… Ireland was different, PJ said “The cogs turned for The Blue Nile in Ireland”.

Radio guys, like Mark Cagney played their music on late night radio, mainstream DJ’s like Gerry Ryan, heard it and liked it and started playing it on daytime radio.

If you look on YouTube you can find clips of Paul bring interviewed on Breakfast TV in Ireland by Mark Cagney who as a late night DJ was one of the first people to play The Blue Nile.

PJ says The Blue Nile were embraced by everybody in Dublin who understood what the Blue Nile were trying to do. The band moved there for a while.

Paul talks about the band deciding to leave Dublin but the night before they left, they had a drive around Stephen’s Green, and changed their mind and stayed in Dublin for another six months.

One of the sweetest messages I got talking about The Blue Nile on Irish radio was from a guy who rang in to say he had been a young barman in a pub on Baggot Street. .

He remembered these three unassuming Scottish guys chatting to him one night at the bar, asking him about himself, his life and his family, and when he asked them about themselves, they told him they were in a band he would never have heard of…

But years later, he now knew all about The Blue Nile and their records and remembered that night in the bar.

Was there anything you left out of the documentary?

There were other people, I interviewed like RTE’s Cathal Murray, Dave Fanning, Dan Hegarty and the TV producer Dave Heffernan I interviewed but there just wasn’t the room to include, and I wasn’t going lose Paul or PJ talking about the recording of Hats to include them.

The Irish actor Liam Cunningham from Game Of Thrones, I interviewed and I couldn’t squeeze in either. He’s so evangelical about The Blue Nile but had never met them. I sent the audio of Liam’s interview to Paul, and Paul rang him up in Dublin to thank him. Which must have been an incredible call for Liam to get.

If I’d had more time, I’d love to have got Billy Sloan, the Scottish journalist and presenter into the doc.

But I ran out of time, on my last day, he was the opposite end of Glasgow. I wouldn’t have made my plane but he provided me with some valuable insight on the band, and was a huge supporter of The Blue Nile.

The documentary was recorded in Dublin and Glasgow, I’d like to say thanks to Frank Kearns at Salt Studios for his help putting it together.

Can we expect more documentaries from you Ken? Are there other band stories you would like to tell?

I’ve had some Irish bands contact me since, asking me would I make a similar radio documentary about them. But my heart wouldn’t be in it… and the story of The Blue Nile can’t be matched.

They were in operating at this crazy time when record companies were selling double – as people bought their entire vinyl collection again on CD.

You can see why there was pressure on The Blue Nile to come up with a second album and a third album.

In Search of The Blue Nile will be broadcast on BBC Scotland at 4pm on 17th April.

* Love it, but can't agree - and we're still waiting for the expanded version of High. Just sayin'...

Tuesday 22 August 2017

Monday 21 August 2017

Jerry Lewis RIP

Jerry Lewis, Mercurial Comedian and Filmmaker, Dies at 91

Dave Kehr

Dave Kehr

The New York Times

20 August 2017

Jerry Lewis, the comedian and filmmaker who was adored by many, disdained by others, but unquestionably a defining figure of American entertainment in the 20th century, died on Sunday morning at his home in Las Vegas. He was 91.

His death was confirmed by his publicist, Candi Cazau.

Mr. Lewis knew success in movies, on television, in nightclubs, on the Broadway stage and in the university lecture hall. His career had its ups and downs, but when it was at its zenith there were few stars any bigger. And he got there remarkably quickly.

Barely out of his teens, he shot to fame shortly after World War II with a nightclub act in which the rakish, imperturbable Dean Martin crooned and the skinny, hyperactive Mr. Lewis capered around the stage, a dangerously volatile id to Mr. Martin’s supremely relaxed ego.

After his break with Mr. Martin in 1956, Mr. Lewis went on to a successful solo career, eventually writing, producing and directing many of his own films.

As a spokesman for the Muscular Dystrophy Association, Mr. Lewis raised vast sums for charity; as a filmmaker of great personal force and technical skill, he made many contributions to the industry, including the invention in 1960 of a device — the video assist, which allowed directors to review their work immediately on the set — still in common use.

A mercurial personality who could flip from naked neediness to towering rage, Mr. Lewis seemed to contain multitudes, and he explored all of them. His ultimate object of contemplation was his own contradictory self, and he turned his obsession with fragmentation, discontinuity and the limits of language into a spectacle that enchanted children, disturbed adults and fascinated postmodernist critics.

Jerry Lewis was born on March 16, 1926, in Newark. Most sources, including his 1982 autobiography, “Jerry Lewis: In Person,” give his birth name as Joseph Levitch. But Shawn Levy, author of the exhaustive 1996 biography “King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis,” unearthed a birth record that gave his first name as Jerome.

His parents, Danny and Rae Levitch, were entertainers — his father a song-and-dance man, his mother a pianist — who used the name Lewis when they appeared in small-time vaudeville and at Catskills resort hotels. The Levitches were frequently on the road and often left Joey, as he was called, in the care of Rae’s mother and her sisters. The experience of being passed from home to home left Mr. Lewis with an enduring sense of insecurity and, as he observed, a desperate need for attention and affection.

An often bored student at Union Avenue School in Irvington, N.J., he began organizing amateur shows with and for his classmates, while yearning to join his parents on tour. During the winter of 1938-39, his father landed an extended engagement at the Hotel Arthur in Lakewood, N.J., and Joey was allowed to go along. Working with the daughter of the hotel’s owners, he created a comedy act in which they lip-synced to popular recordings.

By his 16th birthday, Joey had dropped out of Irvington High and was aggressively looking for work, having adopted the professional name Jerry Lewis to avoid confusion with the nightclub comic Joe E. Lewis. He performed his “record act” solo between features at movie theaters in northern New Jersey, and soon moved on to burlesque and vaudeville.

In 1944 — a 4F classification kept him out of the war — he was performing at the Downtown Theater in Detroit when he met Patti Palmer, a 23-year-old singer. Three months later they were married, and on July 31, 1945, while Patti was living with Jerry’s parents in Newark and he was performing at a Baltimore nightclub, she gave birth to the first of the couple’s six sons, Gary, who in the 1960s had a series of hit records with his band Gary Lewis and the Playboys. The couple divorced in 1980.

Between his first date with Ms. Palmer and the birth of his first son, Mr. Lewis had met Dean Martin, a promising young crooner from Steubenville, Ohio. Appearing on the same bill at the Glass Hat nightclub in Manhattan, the skinny kid from New Jersey was dazzled by the sleepy-eyed singer, who seemed to be everything he was not: handsome, self-assured and deeply, unshakably cool.

When they found themselves on the same bill again at another Manhattan nightclub, the Havana-Madrid, in March 1946, they started fooling around in impromptu sessions after the evening’s last show. Their antics earned the notice of Billboard magazine, whose reviewer wrote, “Martin and Lewis do an afterpiece that has all the makings of a sock act,” using showbiz slang for a successful show.

Mr. Lewis must have remembered those words when he was booked that summer at the 500 Club in Atlantic City. When the singer on the program dropped out, he pushed the club’s owner to hire Mr. Martin to fill the spot. Mr. Lewis and Mr. Martin cobbled together a routine based on their after-hours high jinks at the Havana-Madrid, with Mr. Lewis as a bumbling busboy who kept breaking in on Mr. Martin — dropping trays, hurling food, cavorting like a monkey — without ever ruffling the singer’s sang-froid.

The act was a success. Before the week’s end, they were drawing crowds and winning mentions from Broadway columnists. That September, they returned to the Havana-Madrid in triumph.

Bookings at bigger and better clubs in New York and Chicago followed, and by the summer of 1948 they had reached the pinnacle, headlining at the Copacabana on the Upper East Side of Manhattan while playing one show a night at the 6,000-seat Roxy Theater in Times Square.

The phenomenal rise of Martin and Lewis was like nothing show business had seen before. Partly this was because of the rise of mass media after the war, when newspapers, radio and the emerging medium of television came together to create a new kind of instant celebrity. And partly it was because four years of war and its difficult aftermath were finally lifting, allowing America to indulge a long-suppressed taste for silliness. But primarily it was the unusual chemical reaction that occurred when Martin and Lewis were side by side.

Mr. Lewis’s shorthand definition for their relationship was “sex and slapstick.” But much more was going on: a dialectic between adult and infant, assurance and anxiety, bitter experience and wide-eyed innocence that generated a powerful image of postwar America, a gangly young country suddenly dominant on the world stage.

Among the audience members at the Copacabana was the producer Hal Wallis, who had a distribution deal through Paramount Pictures. Other studios were interested — more so after Martin and Lewis began appearing on live television — but it was Mr. Wallis who signed them to a five-year contract.

He started them off slowly, slipping them into a low-budget project already in the pipeline. Based on a popular radio show, “My Friend Irma” (1949) starred Marie Wilson as a ditsy blonde and Diana Lynn as her levelheaded roommate, with Martin and Lewis providing comic support. The film did well enough to generate a sequel, “My Friend Irma Goes West” (1950), but it was not until “At War With the Army” (1951), an independent production filmed outside Mr. Wallis’s control, that the team took center stage.

“At War With the Army” codified the relationship that ran through all 13 subsequent Martin and Lewis films, positing the pair as unlikely pals whose friendship might be tested by trouble with money or women (usually generated by Mr. Martin’s character), but who were there for each other in the end.

The films were phenomenally successful, and their budgets quickly grew. Some were remakes of Paramount properties — Bob Hope’s 1940 hit “The Ghost Breakers,” for example, became “Scared Stiff” (1953) — while other projects were more adventurous.

“That’s My Boy” (1951), “The Stooge” (1953) and “The Caddy” (1953) approached psychological drama with their forbidding father figures and suggestions of sibling rivalry; Mr. Lewis had a hand in the writing of each. “Artists and Models” (1955) and “Hollywood or Bust” (1956) were broadly satirical looks at American popular culture under the authorial hand of the director Frank Tashlin, who brought a bold graphic style and a flair for wild sight gags to his work. For Mr. Tashlin, Mr. Lewis became a live-action extension of the anarchic characters, like Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, he had worked with as a director of Warner Bros. cartoons.

Mr. Tashlin also functioned as a mentor to Mr. Lewis, who was fascinated with the technical side of filmmaking. Mr. Lewis made 16-millimeter sound home movies and by 1949 was enlisting celebrity friends for short comedies with titles like “How to Smuggle a Hernia Across the Border.” These were amateur efforts, but Mr. Lewis was soon confident enough to advise veteran directors like George Marshall (“Money From Home”) and Norman Taurog (“Living It Up”) on questions of staging. With Mr. Tashlin, he found a director both sympathetic to his style of comedy and technically adept.

But as his artistic aspirations grew and his control over the films in which he appeared increased, Mr. Lewis’s relationship with Mr. Martin became strained. As wildly popular as the team remained, Mr. Martin had come to resent Mr. Lewis’s dominant role in shaping their work and spoke of reviving his solo career as a singer. Mr. Lewis felt betrayed by the man he still worshiped as a role model, and by the time filming began on “Hollywood or Bust” they were barely speaking.

After a farewell performance at the Copacabana on July 25, 1956, 10 years to the day after they had first appeared together in Atlantic City, Mr. Martin and Mr. Lewis went their separate ways.

For Mr. Lewis, an unexpected success mitigated the trauma of the breakup. His recording of “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody,” belted in a style that suggested Al Jolson, became a Top 10 hit, and the album on which it appeared, “Jerry Lewis Just Sings,” climbed to No. 3 on the Billboard chart, outselling anything his former partner had released.

Reassured that his public still loved him, Mr. Lewis returned to film-making with the low-budget, semidramatic “The Delicate Delinquent” and then shifted into overdrive for a series of personal appearances, beginning at the Sands in Las Vegas and culminating with a four-week engagement at the Palace in New York. He signed a contract with NBC for a series of specials and renewed his relationship with the Muscular Dystrophy Association — a charity that he and Mr. Martin had long supported — by hosting a 19-hour telethon.

Mr. Lewis made three uninspired films to complete his obligation to Hal Wallis. He saved his creative energies for the films he produced himself. The first three of those films — “Rock-a-Bye Baby” (1958), “The Geisha Boy” (1958) and “Cinderfella” (1960) — were directed by Mr. Tashlin. After that, finally ready to assume complete control, Mr. Lewis persuaded Paramount to take a chance on “The Bellboy” (1960), a virtually plotless hommage to silent-film comedy that he wrote, directed and starred in, playing a hapless employee of the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach.

It was the beginning of Mr. Lewis’s most creative period. During the next five years, he directed five more films of remarkable stylistic assurance, including “The Ladies Man” (1961), with its huge multistory set of a women’s boardinghouse, and, most notably, “The Nutty Professor” (1963), a variation on “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” in which Mr. Lewis appeared as a painfully shy chemistry professor and his dark alter ego, a swaggering nightclub singer.

With their themes of fragmented identity and their experimental approach to sound, color and narrative structure, Mr. Lewis’s films began to attract the serious consideration of iconoclastic young critics in France. At a time when American film was still largely dismissed by American critics as purely commercial and devoid of artistic interest, Mr. Lewis’s work was held up as a prime example of a personal filmmaker functioning happily within the studio system.

“The Nutty Professor,” a study in split personality that is as disturbing as it is hilarious, is probably the most honored and analyzed of Mr. Lewis’s films. (It was also his personal favorite.) For some critics, the opposition between the helpless, infantile Professor Julius Kelp and the coldly manipulative lounge singer Buddy Love represented a spiteful revision of the old Martin-and-Lewis dynamic. But Buddy seems more pertinently a projection of Mr. Lewis’s darkest fears about himself: a version of the distant, unloving father whom Mr. Lewis had never managed to please as a child, and whom he both despised and desperately wanted to be.

“The Nutty Professor” transcends mere pathology by placing that division within the cultural context of the Kennedy-Hefner-Sinatra era. Buddy Love was what the mid-century American male dreamed of becoming; Julius Kelp was what, deep inside, he suspected he actually was.

“The Nutty Professor” was a hit. But the studio era was coming to an end, Mr. Lewis’s audience was growing old, and by the time he and Paramount parted ways in 1965 his career was in crisis. He tried casting himself in more mature, sophisticated roles — for example, as a prosperous commercial artist in “Three on a Couch,” which he directed for Columbia in 1966. But the public was unconvinced.

He seemed more himself in the multi-role chase comedy “The Big Mouth” (1967) and the World War II farce “Which Way to the Front?” (1970). But his blend of physical comedy and pathos was quickly going out of style in a Hollywood defined by the countercultural irony of “The Graduate” and “MASH.” After “The Day the Clown Cried,” his audacious attempt to direct a comedy-drama set in a Nazi concentration camp, collapsed in litigation in 1972, Mr. Lewis was absent from films for eight years. In that dark period, he struggled with an addiction to the pain killer Percodan.

“Hardly Working,” an independent production that Mr. Lewis directed in Florida, was released in Europe in 1980 and in the United States in 1981. It referred to Mr. Lewis’s marginalized position by casting him as an unemployed circus clown who finds fulfillment in a mundane job with the post office. For Roger Ebert, writing in The Chicago Sun-Times, “Hardly Working” was “one of the worst movies ever to achieve commercial release in this country,” but the film found moderate success in the United States and Europe and has since earned passionate defenders.

A follow-up in 1983, “Smorgasbord” (also known as “Cracking Up”), proved a misfire, and Mr. Lewis never directed another feature film. He did, however, enjoy a revival as an actor, thanks largely to his powerful performance in a dramatic role in Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy” (1982) as a talk-show host kidnapped by an aspiring comedian (Robert De Niro) desperate to become a celebrity. He appeared in the television series “Wiseguy” in 1988 and 1989 as a garment manufacturer threatened by the mob, and was memorable in character roles in Emir Kusturica’s “Arizona Dream” (1993) and Peter Chelsom’s “Funny Bones” (1995). Mr. Lewis played Mr. Applegate (a.k.a. the Devil) in a Broadway revival of the musical “Damn Yankees” in 1995 and later took the show on an international tour.

Although he retained a preternaturally youthful appearance for many years, Mr. Lewis had a series of serious illnesses in his later life, including prostate cancer, pulmonary fibrosis and two heart attacks. Drug treatments caused his weight to balloon alarmingly, though he recovered enough to continue performing well into the new millennium. He was appearing in one-man shows as recently as 2016.

Through it all, Mr. Lewis continued his charity work, serving as national chairman of the Muscular Dystrophy Association and, beginning in 1966, hosting the association’s annual Labor Day weekend telethon. Although some advocates for the rights of the disabled criticized the association’s “Jerry’s Kids” campaign as condescending, the telethon raised about $2 billion during the more than 40 years he was host.

For reasons that remain largely unexplained but were apparently related to a disagreement with the association’s president, Gerald C. Weinberg, the 2010 telethon was Mr. Lewis’s last — he had been scheduled to make an appearance on the 2011 telethon but did not — and he had no further involvement with the charity until 2016, when he lent his support via a promotional video. (The telethon was shortened and eventually discontinued.)

During the 1976 telethon, Frank Sinatra staged an on-air reunion between Mr. Lewis and Mr. Martin, to the visible discomfort of both men. A more lasting reconciliation came in 1987, when Mr. Lewis attended the funeral of Mr. Martin’s oldest son, Dean Paul Martin Jr., a pilot in the California Air National Guard who had been killed in a crash. They continued to speak occasionally until Mr. Martin died in 1995.

In 2005, Mr. Lewis collaborated with James Kaplan on “Dean and Me (A Love Story),” a fond memoir of his years with Mr. Martin in which he placed most of the blame for their breakup on himself. Among Mr. Lewis’s other books was “The Total Film-Maker,” a compendium of his lectures at the film school of the University of Southern California, where he taught, beginning in 1967.

In 1983, Mr. Lewis married SanDee Pitnick, and in 1992 their daughter, Danielle Sara, was born. Besides his wife and daughter, survivors include his sons Christopher, Scott, Gary and Anthony, and several grandchildren.

Although the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences never honored Mr. Lewis for his film work, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for his charitable activity in 2009. His many other honors included two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — one for his movie work, the other for television — and an induction into the Légion d’Honneur, awarded by the French government in 2006.

In 2015, the Library of Congress announced that it had acquired Mr. Lewis’s personal archives. In a statement, he said, “Knowing that the Library of Congress was interested in acquiring my life’s work was one of the biggest thrills of my life.”

Mr. Lewis was officially recognized as a “towering figure in cinema” at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival. The festival’s tribute to him included the screening of a preliminary cut of “Max Rose,” Mr. Lewis’s first movie in almost 20 years, in which he starred as a recently widowed jazz pianist in search of answers about his past. The film did not have its United States premiere until 2016, when it was shown as part of a Lewis tribute at the Museum of Modern Art. Also in 2016, he appeared briefly as the father of Nicolas Cage’s character in the crime drama “The Trust.”

In 2012, Mr. Lewis directed a stage musical in Nashville based on “The Nutty Professor.” The show, with a score by Marvin Hamlisch and book and lyrics by Rupert Holmes, never made it to Broadway, but Mr. Lewis relished the challenge of directing for the stage, a first for him.

“There’s something about the risk, the courage that it takes to face the risk,” he told The New York Times. “I’m not going to get greatness unless I have to go at it with fear and uncertainty.’’

Jerry Lewis, the comedian and filmmaker who was adored by many, disdained by others, but unquestionably a defining figure of American entertainment in the 20th century, died on Sunday morning at his home in Las Vegas. He was 91.

His death was confirmed by his publicist, Candi Cazau.

Mr. Lewis knew success in movies, on television, in nightclubs, on the Broadway stage and in the university lecture hall. His career had its ups and downs, but when it was at its zenith there were few stars any bigger. And he got there remarkably quickly.

Barely out of his teens, he shot to fame shortly after World War II with a nightclub act in which the rakish, imperturbable Dean Martin crooned and the skinny, hyperactive Mr. Lewis capered around the stage, a dangerously volatile id to Mr. Martin’s supremely relaxed ego.

After his break with Mr. Martin in 1956, Mr. Lewis went on to a successful solo career, eventually writing, producing and directing many of his own films.

As a spokesman for the Muscular Dystrophy Association, Mr. Lewis raised vast sums for charity; as a filmmaker of great personal force and technical skill, he made many contributions to the industry, including the invention in 1960 of a device — the video assist, which allowed directors to review their work immediately on the set — still in common use.

A mercurial personality who could flip from naked neediness to towering rage, Mr. Lewis seemed to contain multitudes, and he explored all of them. His ultimate object of contemplation was his own contradictory self, and he turned his obsession with fragmentation, discontinuity and the limits of language into a spectacle that enchanted children, disturbed adults and fascinated postmodernist critics.

Jerry Lewis was born on March 16, 1926, in Newark. Most sources, including his 1982 autobiography, “Jerry Lewis: In Person,” give his birth name as Joseph Levitch. But Shawn Levy, author of the exhaustive 1996 biography “King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis,” unearthed a birth record that gave his first name as Jerome.

His parents, Danny and Rae Levitch, were entertainers — his father a song-and-dance man, his mother a pianist — who used the name Lewis when they appeared in small-time vaudeville and at Catskills resort hotels. The Levitches were frequently on the road and often left Joey, as he was called, in the care of Rae’s mother and her sisters. The experience of being passed from home to home left Mr. Lewis with an enduring sense of insecurity and, as he observed, a desperate need for attention and affection.

An often bored student at Union Avenue School in Irvington, N.J., he began organizing amateur shows with and for his classmates, while yearning to join his parents on tour. During the winter of 1938-39, his father landed an extended engagement at the Hotel Arthur in Lakewood, N.J., and Joey was allowed to go along. Working with the daughter of the hotel’s owners, he created a comedy act in which they lip-synced to popular recordings.

By his 16th birthday, Joey had dropped out of Irvington High and was aggressively looking for work, having adopted the professional name Jerry Lewis to avoid confusion with the nightclub comic Joe E. Lewis. He performed his “record act” solo between features at movie theaters in northern New Jersey, and soon moved on to burlesque and vaudeville.

In 1944 — a 4F classification kept him out of the war — he was performing at the Downtown Theater in Detroit when he met Patti Palmer, a 23-year-old singer. Three months later they were married, and on July 31, 1945, while Patti was living with Jerry’s parents in Newark and he was performing at a Baltimore nightclub, she gave birth to the first of the couple’s six sons, Gary, who in the 1960s had a series of hit records with his band Gary Lewis and the Playboys. The couple divorced in 1980.

Between his first date with Ms. Palmer and the birth of his first son, Mr. Lewis had met Dean Martin, a promising young crooner from Steubenville, Ohio. Appearing on the same bill at the Glass Hat nightclub in Manhattan, the skinny kid from New Jersey was dazzled by the sleepy-eyed singer, who seemed to be everything he was not: handsome, self-assured and deeply, unshakably cool.

When they found themselves on the same bill again at another Manhattan nightclub, the Havana-Madrid, in March 1946, they started fooling around in impromptu sessions after the evening’s last show. Their antics earned the notice of Billboard magazine, whose reviewer wrote, “Martin and Lewis do an afterpiece that has all the makings of a sock act,” using showbiz slang for a successful show.

Mr. Lewis must have remembered those words when he was booked that summer at the 500 Club in Atlantic City. When the singer on the program dropped out, he pushed the club’s owner to hire Mr. Martin to fill the spot. Mr. Lewis and Mr. Martin cobbled together a routine based on their after-hours high jinks at the Havana-Madrid, with Mr. Lewis as a bumbling busboy who kept breaking in on Mr. Martin — dropping trays, hurling food, cavorting like a monkey — without ever ruffling the singer’s sang-froid.

The act was a success. Before the week’s end, they were drawing crowds and winning mentions from Broadway columnists. That September, they returned to the Havana-Madrid in triumph.

Bookings at bigger and better clubs in New York and Chicago followed, and by the summer of 1948 they had reached the pinnacle, headlining at the Copacabana on the Upper East Side of Manhattan while playing one show a night at the 6,000-seat Roxy Theater in Times Square.

The phenomenal rise of Martin and Lewis was like nothing show business had seen before. Partly this was because of the rise of mass media after the war, when newspapers, radio and the emerging medium of television came together to create a new kind of instant celebrity. And partly it was because four years of war and its difficult aftermath were finally lifting, allowing America to indulge a long-suppressed taste for silliness. But primarily it was the unusual chemical reaction that occurred when Martin and Lewis were side by side.

Mr. Lewis’s shorthand definition for their relationship was “sex and slapstick.” But much more was going on: a dialectic between adult and infant, assurance and anxiety, bitter experience and wide-eyed innocence that generated a powerful image of postwar America, a gangly young country suddenly dominant on the world stage.

Among the audience members at the Copacabana was the producer Hal Wallis, who had a distribution deal through Paramount Pictures. Other studios were interested — more so after Martin and Lewis began appearing on live television — but it was Mr. Wallis who signed them to a five-year contract.

He started them off slowly, slipping them into a low-budget project already in the pipeline. Based on a popular radio show, “My Friend Irma” (1949) starred Marie Wilson as a ditsy blonde and Diana Lynn as her levelheaded roommate, with Martin and Lewis providing comic support. The film did well enough to generate a sequel, “My Friend Irma Goes West” (1950), but it was not until “At War With the Army” (1951), an independent production filmed outside Mr. Wallis’s control, that the team took center stage.

“At War With the Army” codified the relationship that ran through all 13 subsequent Martin and Lewis films, positing the pair as unlikely pals whose friendship might be tested by trouble with money or women (usually generated by Mr. Martin’s character), but who were there for each other in the end.

The films were phenomenally successful, and their budgets quickly grew. Some were remakes of Paramount properties — Bob Hope’s 1940 hit “The Ghost Breakers,” for example, became “Scared Stiff” (1953) — while other projects were more adventurous.

“That’s My Boy” (1951), “The Stooge” (1953) and “The Caddy” (1953) approached psychological drama with their forbidding father figures and suggestions of sibling rivalry; Mr. Lewis had a hand in the writing of each. “Artists and Models” (1955) and “Hollywood or Bust” (1956) were broadly satirical looks at American popular culture under the authorial hand of the director Frank Tashlin, who brought a bold graphic style and a flair for wild sight gags to his work. For Mr. Tashlin, Mr. Lewis became a live-action extension of the anarchic characters, like Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, he had worked with as a director of Warner Bros. cartoons.

Mr. Tashlin also functioned as a mentor to Mr. Lewis, who was fascinated with the technical side of filmmaking. Mr. Lewis made 16-millimeter sound home movies and by 1949 was enlisting celebrity friends for short comedies with titles like “How to Smuggle a Hernia Across the Border.” These were amateur efforts, but Mr. Lewis was soon confident enough to advise veteran directors like George Marshall (“Money From Home”) and Norman Taurog (“Living It Up”) on questions of staging. With Mr. Tashlin, he found a director both sympathetic to his style of comedy and technically adept.

But as his artistic aspirations grew and his control over the films in which he appeared increased, Mr. Lewis’s relationship with Mr. Martin became strained. As wildly popular as the team remained, Mr. Martin had come to resent Mr. Lewis’s dominant role in shaping their work and spoke of reviving his solo career as a singer. Mr. Lewis felt betrayed by the man he still worshiped as a role model, and by the time filming began on “Hollywood or Bust” they were barely speaking.

After a farewell performance at the Copacabana on July 25, 1956, 10 years to the day after they had first appeared together in Atlantic City, Mr. Martin and Mr. Lewis went their separate ways.

For Mr. Lewis, an unexpected success mitigated the trauma of the breakup. His recording of “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody,” belted in a style that suggested Al Jolson, became a Top 10 hit, and the album on which it appeared, “Jerry Lewis Just Sings,” climbed to No. 3 on the Billboard chart, outselling anything his former partner had released.

Reassured that his public still loved him, Mr. Lewis returned to film-making with the low-budget, semidramatic “The Delicate Delinquent” and then shifted into overdrive for a series of personal appearances, beginning at the Sands in Las Vegas and culminating with a four-week engagement at the Palace in New York. He signed a contract with NBC for a series of specials and renewed his relationship with the Muscular Dystrophy Association — a charity that he and Mr. Martin had long supported — by hosting a 19-hour telethon.

Mr. Lewis made three uninspired films to complete his obligation to Hal Wallis. He saved his creative energies for the films he produced himself. The first three of those films — “Rock-a-Bye Baby” (1958), “The Geisha Boy” (1958) and “Cinderfella” (1960) — were directed by Mr. Tashlin. After that, finally ready to assume complete control, Mr. Lewis persuaded Paramount to take a chance on “The Bellboy” (1960), a virtually plotless hommage to silent-film comedy that he wrote, directed and starred in, playing a hapless employee of the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach.

It was the beginning of Mr. Lewis’s most creative period. During the next five years, he directed five more films of remarkable stylistic assurance, including “The Ladies Man” (1961), with its huge multistory set of a women’s boardinghouse, and, most notably, “The Nutty Professor” (1963), a variation on “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” in which Mr. Lewis appeared as a painfully shy chemistry professor and his dark alter ego, a swaggering nightclub singer.

With their themes of fragmented identity and their experimental approach to sound, color and narrative structure, Mr. Lewis’s films began to attract the serious consideration of iconoclastic young critics in France. At a time when American film was still largely dismissed by American critics as purely commercial and devoid of artistic interest, Mr. Lewis’s work was held up as a prime example of a personal filmmaker functioning happily within the studio system.

“The Nutty Professor,” a study in split personality that is as disturbing as it is hilarious, is probably the most honored and analyzed of Mr. Lewis’s films. (It was also his personal favorite.) For some critics, the opposition between the helpless, infantile Professor Julius Kelp and the coldly manipulative lounge singer Buddy Love represented a spiteful revision of the old Martin-and-Lewis dynamic. But Buddy seems more pertinently a projection of Mr. Lewis’s darkest fears about himself: a version of the distant, unloving father whom Mr. Lewis had never managed to please as a child, and whom he both despised and desperately wanted to be.

“The Nutty Professor” transcends mere pathology by placing that division within the cultural context of the Kennedy-Hefner-Sinatra era. Buddy Love was what the mid-century American male dreamed of becoming; Julius Kelp was what, deep inside, he suspected he actually was.

“The Nutty Professor” was a hit. But the studio era was coming to an end, Mr. Lewis’s audience was growing old, and by the time he and Paramount parted ways in 1965 his career was in crisis. He tried casting himself in more mature, sophisticated roles — for example, as a prosperous commercial artist in “Three on a Couch,” which he directed for Columbia in 1966. But the public was unconvinced.

He seemed more himself in the multi-role chase comedy “The Big Mouth” (1967) and the World War II farce “Which Way to the Front?” (1970). But his blend of physical comedy and pathos was quickly going out of style in a Hollywood defined by the countercultural irony of “The Graduate” and “MASH.” After “The Day the Clown Cried,” his audacious attempt to direct a comedy-drama set in a Nazi concentration camp, collapsed in litigation in 1972, Mr. Lewis was absent from films for eight years. In that dark period, he struggled with an addiction to the pain killer Percodan.

“Hardly Working,” an independent production that Mr. Lewis directed in Florida, was released in Europe in 1980 and in the United States in 1981. It referred to Mr. Lewis’s marginalized position by casting him as an unemployed circus clown who finds fulfillment in a mundane job with the post office. For Roger Ebert, writing in The Chicago Sun-Times, “Hardly Working” was “one of the worst movies ever to achieve commercial release in this country,” but the film found moderate success in the United States and Europe and has since earned passionate defenders.

A follow-up in 1983, “Smorgasbord” (also known as “Cracking Up”), proved a misfire, and Mr. Lewis never directed another feature film. He did, however, enjoy a revival as an actor, thanks largely to his powerful performance in a dramatic role in Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy” (1982) as a talk-show host kidnapped by an aspiring comedian (Robert De Niro) desperate to become a celebrity. He appeared in the television series “Wiseguy” in 1988 and 1989 as a garment manufacturer threatened by the mob, and was memorable in character roles in Emir Kusturica’s “Arizona Dream” (1993) and Peter Chelsom’s “Funny Bones” (1995). Mr. Lewis played Mr. Applegate (a.k.a. the Devil) in a Broadway revival of the musical “Damn Yankees” in 1995 and later took the show on an international tour.

Although he retained a preternaturally youthful appearance for many years, Mr. Lewis had a series of serious illnesses in his later life, including prostate cancer, pulmonary fibrosis and two heart attacks. Drug treatments caused his weight to balloon alarmingly, though he recovered enough to continue performing well into the new millennium. He was appearing in one-man shows as recently as 2016.

Through it all, Mr. Lewis continued his charity work, serving as national chairman of the Muscular Dystrophy Association and, beginning in 1966, hosting the association’s annual Labor Day weekend telethon. Although some advocates for the rights of the disabled criticized the association’s “Jerry’s Kids” campaign as condescending, the telethon raised about $2 billion during the more than 40 years he was host.

For reasons that remain largely unexplained but were apparently related to a disagreement with the association’s president, Gerald C. Weinberg, the 2010 telethon was Mr. Lewis’s last — he had been scheduled to make an appearance on the 2011 telethon but did not — and he had no further involvement with the charity until 2016, when he lent his support via a promotional video. (The telethon was shortened and eventually discontinued.)

During the 1976 telethon, Frank Sinatra staged an on-air reunion between Mr. Lewis and Mr. Martin, to the visible discomfort of both men. A more lasting reconciliation came in 1987, when Mr. Lewis attended the funeral of Mr. Martin’s oldest son, Dean Paul Martin Jr., a pilot in the California Air National Guard who had been killed in a crash. They continued to speak occasionally until Mr. Martin died in 1995.

In 2005, Mr. Lewis collaborated with James Kaplan on “Dean and Me (A Love Story),” a fond memoir of his years with Mr. Martin in which he placed most of the blame for their breakup on himself. Among Mr. Lewis’s other books was “The Total Film-Maker,” a compendium of his lectures at the film school of the University of Southern California, where he taught, beginning in 1967.

In 1983, Mr. Lewis married SanDee Pitnick, and in 1992 their daughter, Danielle Sara, was born. Besides his wife and daughter, survivors include his sons Christopher, Scott, Gary and Anthony, and several grandchildren.

Although the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences never honored Mr. Lewis for his film work, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for his charitable activity in 2009. His many other honors included two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — one for his movie work, the other for television — and an induction into the Légion d’Honneur, awarded by the French government in 2006.

In 2015, the Library of Congress announced that it had acquired Mr. Lewis’s personal archives. In a statement, he said, “Knowing that the Library of Congress was interested in acquiring my life’s work was one of the biggest thrills of my life.”

Mr. Lewis was officially recognized as a “towering figure in cinema” at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival. The festival’s tribute to him included the screening of a preliminary cut of “Max Rose,” Mr. Lewis’s first movie in almost 20 years, in which he starred as a recently widowed jazz pianist in search of answers about his past. The film did not have its United States premiere until 2016, when it was shown as part of a Lewis tribute at the Museum of Modern Art. Also in 2016, he appeared briefly as the father of Nicolas Cage’s character in the crime drama “The Trust.”

In 2012, Mr. Lewis directed a stage musical in Nashville based on “The Nutty Professor.” The show, with a score by Marvin Hamlisch and book and lyrics by Rupert Holmes, never made it to Broadway, but Mr. Lewis relished the challenge of directing for the stage, a first for him.

“There’s something about the risk, the courage that it takes to face the risk,” he told The New York Times. “I’m not going to get greatness unless I have to go at it with fear and uncertainty.’’

Sunday 20 August 2017

Saturday 19 August 2017

Sir Bruce Forsyth RIP

Sir Bruce Forsyth obituary: a TV presenter in a class of his own

Entertainer who began his career in variety and became an enduringly popular TV hostMichael Coveney

The Guardian

Friday 18 August 2017

Bruce Forsyth, who has died aged 89, was associated with some of the most successful shows in television history, from Sunday Night at the London Palladium in the late 1950s to The Generation Game in the 1970s and, for a decade from 2004, Strictly Come Dancing, a light-entertainment phenomenon that attracts a third of the viewing audience to BBC1 on a Saturday night.

As a compere, game-show host and fleet-footed comedian, he was in a class of his own, providing an authentic link between the old days of variety, where he started as a youthful sensation during the second world war, and the new craze for audience participation and reality television. He had appeared in variety (and indeed on the golf course) with the great Max Miller, admiring the way Miller put his foot on the footlights to lean over and reach out to the audience, but his real idol (and good friend) was Sammy Davis Jr, and he aspired to the same distinction as an all-rounder on the variety stage.

His flashing, sometimes tetchy-seeming, personality and distinctive “edge” paradoxically endeared him to audiences – he wasn’t lovable, or “cuddly” like Ronnie Corbett, for instance; he used the game-show participants or the celebrity dancers on Strictly to feed his own performance and impeccably timed double-takes (expressions of mock disbelief or patronising, po-faced quasi-pity), to the camera, in the style of Eric Morecambe.

Friday 18 August 2017

Bruce Forsyth, who has died aged 89, was associated with some of the most successful shows in television history, from Sunday Night at the London Palladium in the late 1950s to The Generation Game in the 1970s and, for a decade from 2004, Strictly Come Dancing, a light-entertainment phenomenon that attracts a third of the viewing audience to BBC1 on a Saturday night.

As a compere, game-show host and fleet-footed comedian, he was in a class of his own, providing an authentic link between the old days of variety, where he started as a youthful sensation during the second world war, and the new craze for audience participation and reality television. He had appeared in variety (and indeed on the golf course) with the great Max Miller, admiring the way Miller put his foot on the footlights to lean over and reach out to the audience, but his real idol (and good friend) was Sammy Davis Jr, and he aspired to the same distinction as an all-rounder on the variety stage.

His flashing, sometimes tetchy-seeming, personality and distinctive “edge” paradoxically endeared him to audiences – he wasn’t lovable, or “cuddly” like Ronnie Corbett, for instance; he used the game-show participants or the celebrity dancers on Strictly to feed his own performance and impeccably timed double-takes (expressions of mock disbelief or patronising, po-faced quasi-pity), to the camera, in the style of Eric Morecambe.

Forsyth sometimes expressed regret at being sidetracked by game shows, but his stage career never really took off, and his films were few. His resilience as a personality on television, however, was remarkable. He bounced back from the disappointment of being moved to the afternoon schedules by television executives at ITV; there was a huge bust-up in 2000 when he left Play Your Cards Right and denounced David Liddiment, the new controller, as someone who had stripped him of his dignity.

But having launched a comeback as an unlikely guest host on the BBC’s satirical flagship Have I Got News for You in 2003, he regained his place in the national affection with Strictly, and in 2011 was knighted following a noisy public campaign.

He retained a trim, dapper appearance – his trademark Rodin’s Thinker pose in silhouette dates from The Generation Game – with his skateboard chin and natty moustache, and a hairstyle that had been remodelled over the years from tidy teddy boy quiffs at the Windmill theatre to an ever more carefully structured coiffure of corn-coloured thatch.

And he displayed a true vaudevillian’s talent for catchphrases; as Tommy Trinder (whom he succeeded on Sunday Night at the London Palladium) had “You lucky people”, or Arthur Askey “I thank-yeaow”, so Forsyth patented “I’m in charge” at the Palladium followed by “Nice to see you … to see you, nice!” and “Didn’t he do well?” on The Generation Game.

In a 2011 interview with Mick Brown in the Daily Telegraph, he attributed his longevity, and extraordinary energy, to his experience in variety: “This other person turns up, and thank goodness I’ve never known him to be late. He just gets into me, and I go and perform, and that’s what I do.” In 2013, at the age of 85, he became the oldest performer to appear at the Glastonbury festival, in the same year that the Rolling Stones also made a belated debut there.

Forsyth, who was born in Edmonton, north London, was the third child and second son of John Forsyth-Johnson, a relatively prosperous garage owner, and his wife, Florence (nee Pocknell), both Salvation Army members. He was educated at Latymer grammar school, Edmonton, but left without any qualifications, having become obsessed with tap dancing after seeing Fred Astaire movies at the local Regal cinema; he made a BBC television debut in 1939 on the Jasmine Bligh talent show.

On the outbreak of war, he was evacuated to Clacton-on-Sea in Essex, but insisted on coming home after just three days, continuing his dance lessons with Tilly Vernon and even running his own classes in one of his father’s garages. He launched his career as Boy Bruce, the Mighty Atom, at the Theatre Royal, Bilston, in Staffordshire, in 1942, wearing a satin suit made by his mother and playing the accordion, ukulele and banjo.

There followed a long, hard slog of 16 years of variety halls and summer shows around the country, interrupted only by two years of national service with the RAF in Warrington and Carlisle after the war (in which his older brother, John, was killed on an RAF training exercise in Scotland in 1943; his body was never found).

Forsyth, who led a busy and sometimes complicated private life, with a penchant for showgirls, singers and beauty queens, made his Windmill theatre debut in 1953, performing impressions of Tommy Cooper (already a cult figure); he also married one of the Windmill dancers, Penny Calvert, and they formed a song-and-dance double act.

During a third summer season at Babbacombe in Devon in 1957, another dance act recommended Bruce to their agent, Billy Marsh, and this contact with a key figure in the all-powerful Bernard Delfont organisation led to a booking on a television show, New Look, followed by the breakthrough Sunday Night at the London Palladium gig in September 1958; in black and white, and always broadcast “live” on ATV, Forsyth demonstrated his genius for improvisation and ad-libbing as he shuffled and chivvied the audience participants in physical competitions and word games in the show’s Beat the Clock segment.

On that first show, he also hosted the comedy act of Jimmy Jewel and Ben Warriss, the singers Anne Shelton and David Whitfield, and a fellow Windmill alumnus, Peter Sellers; a contract for three weeks was stretched to three years, and at Christmas he headlined the Palladium pantomime, Sleeping Beauty, alongside Charlie Drake, Bernard Bresslaw and the singer Edmund Hockridge.

By 1961 he was compering what he called the best ever Royal Variety Show –Kenny Ball, Morecambe and Wise, Arthur Haynes, Shirley Bassey, George Burns, Jack Benny, Davis, Frankie Vaughan and Maurice Chevalier; Forsyth read out a poem written by AP Herbert for the Queen Mother – and he was earning a then-enormous salary of £1,000 a week.

His jazz piano playing, influenced by George Shearing and Bill Evans, was better than competent, and his high level of versatility was fully apparent in 1964 when he made a cabaret debut at the new Talk of the Town (his impressions included Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Anthony Newley and Frank Ifield, as well as Davis) and starred in Little Me, his one West End musical, at the Cambridge.

Little Me, with a book by Neil Simon, songs by Cy Coleman and Carolyn Leigh, and choreography by Bob Fosse, involved Forsyth in seven roles and 29 costume changes as he played the various lovers of an old movie star, Belle Poitrine (Real Live Girl is the best known song). The show had starred the great Sid Caesar on Broadway but Bruce made the roles his own – they ranged from a virginal doughboy and goose-stepping movie director to a scaly old miser and billionaire newspaper baron. He scored a critical success, although the show ran for only 10 months.

A film debut followed in Robert Wise’s Star! (1968) with Julie Andrews as Gertrude Lawrence – Bruce played her father and did a music hall turn with Beryl Reid as her mother – and Daniel Massey as Noël Coward, and then he stalled badly in Newley’s self-indulgent autobiographical fantasy Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? (1969) with Joan Collins and Milton Berle. He showed up to better effect as a vivid spiv in the Disney film Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971), which starred Angela Lansbury and David Tomlinson.

By now he was established on The Generation Game, an early evening “hook” (attracting a peak audience of 21m viewers) for the BBC’s now-legendary Saturday stay-at-home night of Doctor Who, Morecambe and Wise, The Duchess of Duke Street, Match of the Day and Michael Parkinson’s chat show. “Let’s meet the eight who are going to generate,” said Brucie, after encouraging his gorgeous blonde assistant, Anthea Redfern, to “give us a twirl”. (Redfern became his second wife; he had met her at a Miss Lovely Legs competition in a London nightclub.) The contestants (an older and a younger member in each of the four family duos) played for prizes they had to memorise as they passed by on a conveyor belt laden with kitchen appliances, fondue sets and cuddly toys.

During this decade, Forsyth also toured with his one-man show and realised a lifelong ambition in taking it to Broadway in 1979. The New York Times raved but other reviews were mixed and Forsyth never really recovered from being branded a Broadway flop with jokes older than Beowulf.

He was always uneasy with the press, which had relished his colourful private life. After his first wife, Penny, and one daughter sold stories to the tabloids, he instigated a 10-year ban on talking to them and made a digest of selected favourable commentary in the programme for his show when he reprised it at the Palladium, under the heading “Some Reviews You Might Not Have Heard About”.

In 1983 he married for the third time, to Wilnelia Merced – a model and beauty queen whom he had met as a fellow judge on the 1980 Miss World contest. He maintained his popularity throughout sundry ITV game shows in the 1980s before returning to The Generation Game in 1990 for four more years, with a new assistant, the singer/dancer Rosemarie Ford.

A lifelong golf fanatic, Forsyth lived in a house on the Wentworth Estate in Surrey from 1975; he could walk from his back garden straight on to the first tee of the golf course. In 2010 he appeared on the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are? programme, and was grimly affected – though he never shed a tear; he didn’t “do” crying – to discover that his great-grandfather, a landscape gardener, had deserted two families and died in poverty.

He was voted BBC TV Personality of the Year in 1991, and was made OBE in 1998, CBE in 2006 and a fellow of Bafta in 2008.

He is survived by Wilnelia, and their son, Jonathan Joseph, or JJ; by three daughters, Debbie, Julie and Laura, from his first marriage, which ended in divorce; two daughters, Charlotte and Louisa, from his second marriage, which ended in divorce; and by nine grandchildren.

Friday 18 August 2017

Dead Poets Society #46 Bob Kaufman: Bagel Shop Jazz

Bagel Shop Jazz by Bob Kaufman

Memory formed echoes of a generation past

Beating into now.

Nightfall creatures, eating each other

Over a noisy cup of coffee.

Mulberry-eyed girls in black stockings,

Smelling vaguely of mint jelly and last night's bongo

drummer,

Making profound remarks on the shapes of navels,

Wondering how the short Sunset week

Became the long Grant Avenue night,

Love tinted, beat angels,

Doomed to see their coffee dreams

Crushed on the floors of time,

As they fling their arrow legs

To the heavens,

Losing their doubts in the beat.

Turtle-neck angel guys, black-haired dungaree guys,

Caesar-jawed, with synagogue eyes,

World travelers on the forty-one bus,

Mixing jazz with paint talk,

High rent, Bartok, classical murders,

The pot shortage and last night's bust.

Lost in a dream world,

Where time is told with a beat.

Coffee-faced Ivy Leaguers, in Cambridge jackets,

Whose personal Harvard was a fillmore district step,

Weighted down with conga drums,

The ancestral cross, the Othello-laid curse,

Talking of Bird and Diz and Miles,

The secret terrible hurts,

Wrapped in cool hipster smiles,

Telling themselves, under the talk,

This shot must be the end,

Hoping the beat is really the truth.

The guilty police arrive.

Brief, beautiful shadows, burned on walls of night.

Thursday 17 August 2017

Last night's set lists

At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

Can't Help Falling In Love

Ron Elderly: -

Can't Help Falling In Love

Just My Imagination

Da Elderly: -

I'm Just A Loser

In The Morning Light

The Elderly Brothers: -

No Reply

Mailman Bring Me No More Blues

When You Walk In The Room

It Doesn't Matter Anymore