Monday 30 March 2020

Saturday 28 March 2020

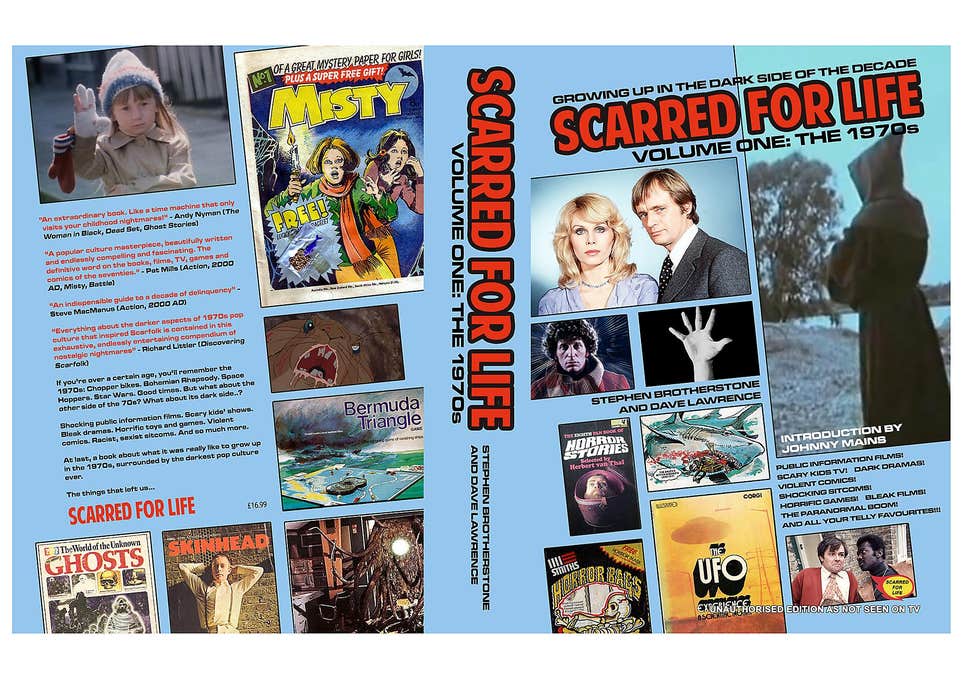

Scarred for Life: Growing Up in the Dark Side of the Decade

Here's a really enjoyable and, at times, eye-opening book to appeal to people of a certain age; people who grew up in the 70s and watched some bizarre television - often aimed specifically at kids - or who read some very odd comics, including things you'd be lucky to get away with now. In fact, American comics aside, do kids even read comics any more? Some of the featured shows are, of course, a throw over from the 60s (European imports, for example) and not all were aimed at children (the BBC's M R James adaptations, G F Newman's Law and Order, for example) and we can only hope that someone writes another volume on that period...

Scarred for life: How the pop culture of the Seventies had such a lasting effect on children

The seventies was proliferated by public information films warning of polished floor man-traps, human sacrifice on afternoon TV and ultraviolent comics, says David Barnett

David Barnett

The Independent

Tuesday 30 May 2017

‘Scarred for Life’ is a traumatic reminder of just how scary the Seventies were for kids.

Stephen Brotherstone will be 47 next month, but every time he comes to a road he stands well back from the kerb, looks right, looks left, and looks right again, and only crosses when it is clear.

“I can’t help it,” he says. “I had the Green Cross Code burned into my head as a kid.”

Brotherstone, from Liverpool, is a child of the Seventies, and thus was educated in the ways of safety and sensibility by the public information films that proliferated in the decade. As well as knowing how to cross the road, he is fully aware that you never climb an electricity pylon to retrieve a kite, that if you put a rug on a polished floor you might as well set a man-trap, and that the fool-hardy child who plays near open water will fall victim to a hooded spirit voiced by Donald Pleasence.

“I honestly think the public information films are the last great art form waiting to be recognised,” he says. “They’re wonderful, like complete horror films distilled into 30 seconds.”

The films have a place in a new book written by Stephen and Dave Lawrence called Scarred for Life, and they are just one piece of the rather horrific puzzle that was 1970s popular culture aimed at children. Last month the Daily Mail lambasted Jeremy Corbyn for the leaked Labour manifesto that would “take us back to the 1970s”. They were thinking more about renationalisation, tax hikes and strikes though, not the relentless and often disturbing cavalcade of entertainment that left a generation ever so slightly traumatised.

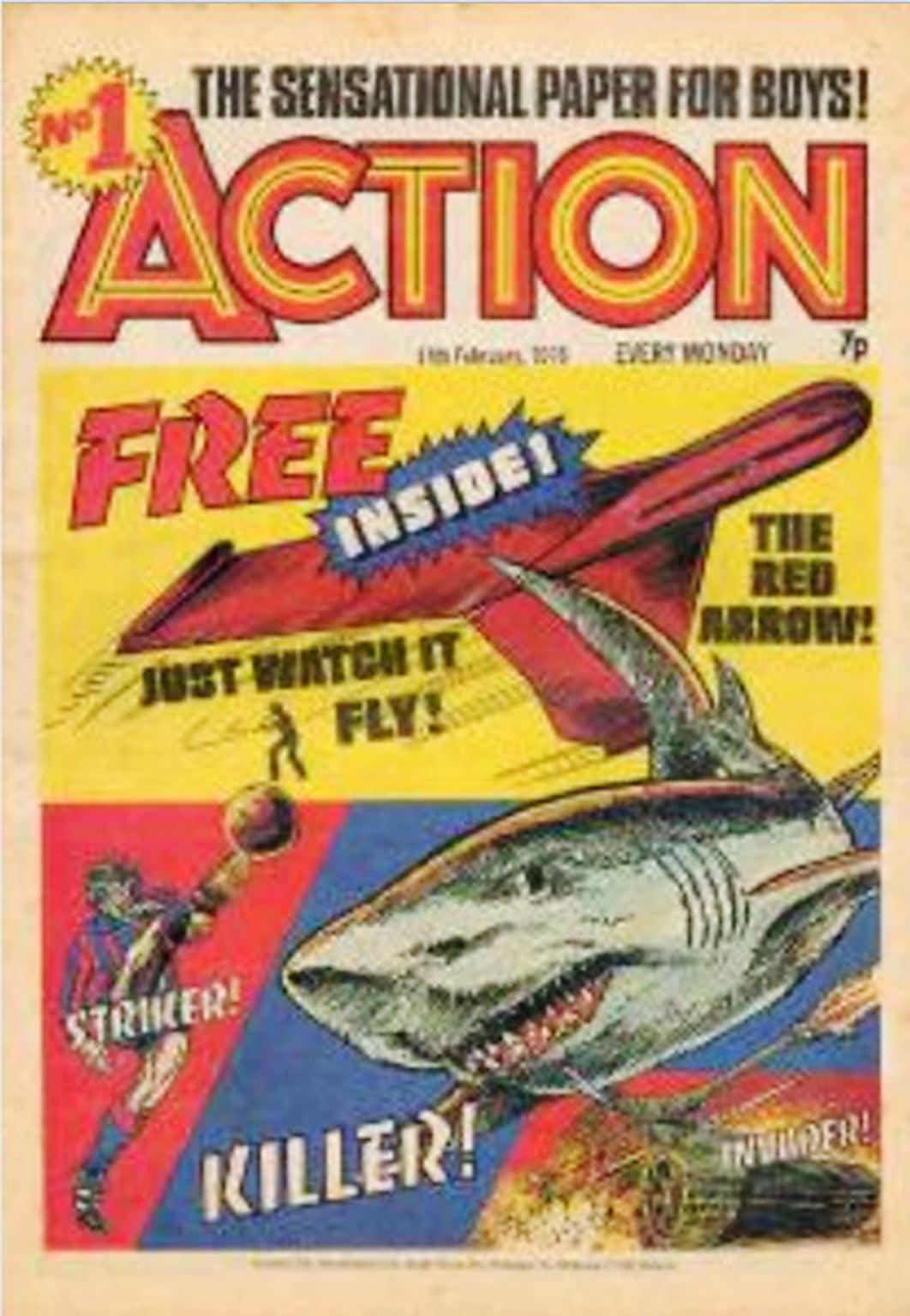

We are talking the likes of TV’s Sapphire and Steel, the otherworldly agents played by David McCallum and Joanna Lumley who investigated the stuff of young nightmares – people trapped in photographs, spooky nursery rhymes. We are talking 1977’s kids’ TV series Children of the Stones, which got youngsters’ anxiety levels radged right up from the moment the wailing theme tune began. We are talking the ultraviolent Action comic, which gleefully replicated all the X-rated movies kids could not watch in comic book form, until Frank Bough ripped up a copy on TV in a righteous fury and it was pulled by the publishers. It is all in the book, and much more besides.

At more than 730 pages, this is a labour of love and a traumatic reminder of just how scary the Seventies were for kids. Put more than two 40-somethings in a room and sooner or later they’ll talk about the pop culture of their day, and how it was so often inappropriate to contemporary mores. Which is exactly how Scarred for Life came about.

Brotherstone works in the Liverpool branch of the comics-and-geek-culture chain Forbidden Planet, and one day got talking with regular customer Dave Lawrence about the TV shows of their youth. He says, “Everything we remembered seemed to be horrific and bleak in some way. As soon as I got home I started looking on the internet for books on the subject, but I was pretty amazed that although I could get books about space hoppers and glam rock, there was nothing that really looked at all this stuff from the Seventies which was massively scary.”

A colleague suggested he write one himself, which he laughed off. But when Lawrence offered to co-write and research, he thought again, and together they embarked on a three-and-a-half-year journey to document their childhood scares, which has just now borne fruit.

Brotherstone and I swap memories of shows that freaked us out. “Remember The Feathered Serpent?” he says. I did. ITV’s attempt at a historical drama for kids, set in ancient Mexico. “They had human sacrifice and all sorts at 4.30 in the afternoon!” he adds.

But what was it about the Seventies that produced such weird, eerie and horrifying stuff for kids? Brotherstone’s theory is that it was a hangover from the permissive Sixties. “At the end of that decade the shutters sort of came up and film-makers and artists started doing a lot of stuff that they felt was free of censorship,” he says. “I think they felt so free that they just went for it in a big way, there was possibly an element of naivety in what people thought was appropriate for kids. These days there are so many guidelines about what children should and shouldn’t be exposed to, and that sort of thing wasn’t in evidence much back in the Seventies, which is why we had a lot of stuff that looks really scary and disturbing today.”

Young people prepare to yawn, but it was a different world back then. We knew we should not talk to strangers or the terrifying bogeyman of “the dirty old man” (both Brotherstone and I realise that back then we assumed parents meant “tramps” rather than today’s more ubiquitous paedophile), but we still went out all day without letting our mums and dads know where we were going. We roamed the bounds of our territory, and occasionally beyond, without the safety net of a mobile phone if we needed to speak to home. We scuffed our knees and ripped our clothes and carried big sticks.

“It all didn’t do us any harm,” says Brotherstone, laughing before adding, “God, that’s such a cliche. But it feels so different today.”

One thing that has also changed is the way we consume our culture. In these days of catch-up TV, binge-watching box-sets and downloading movies, it is perhaps hard to conceive of the immediacy and transient nature of TV especially back then – which is why Brotherstone thinks we remember stuff from the Seventies with such clarity.

“These days a young person will be watching a TV show at the same time as being on their phone or doing something else; they know they don’t have to give it their full attention because they can catch up and watch it again anytime,” he says. “But in the Seventies we really, properly watched stuff. You had to. So you’d sit down in front of the TV and you’d tell everybody to be quiet and you’d concentrate, because it was your one and only chance to see the show. It wasn’t going to be repeated, we didn’t have video recorders, we couldn’t just watch it again.

‘Children of the Stones’ has been called ‘the scariest programme ever made for kids’

“And I think that’s why we remember the adverts and the public information films so clearly. We couldn’t fast-forward through the ads so we had to sit through them while we were waiting for Magpie or whatever to start again, and they just stuck in our heads.”

Scarred for Life does not just focus on horror and science fiction flavoured TV and films, though it does so lovingly and exhaustingly, but also looks at toys, sweets and light entertainment shows of the decade, for example The Black and White Minstrel Show. If you do not know what that is, it was essentially a bunch of white people wearing blackface for song and dance numbers. And no-one batted an eyelid.

One of the nice touches of the book is that it views Seventies culture not as an academic treatise, and not even with adult nostalgia, but through the lens of the children that Brotherstone and Lawrence were at the time.

“We originally intended to cover the Eighties as well,” says Brotherstone, “but it soon became apparent we would have far too much material. So we’re doing a second book, and we’ll be looking at that from the perspective of us becoming teenagers in that decade.”

While the Eighties had its share of inappropriate consumer culture, being the decade of the video nasty for example, it will also heavily focus on the Cold War that dominated and the very real threat of nuclear extinction. Brotherstone vividly recalls having his first anxiety attack – though he did not know what it was at the time – over the thought of everyone he knew and loved dying in a nuclear holocaust. “I was 13,” he says. “That’s going to come into volume two a lot, how that fear influenced culture, from the terrifying Threads to ‘99 Red Balloons’.”

But that is a work in progress, and it is book one of Scarred for Life with its sometimes quaint, sometimes paralysingly horrifying portrayal of the 1970s through its child-focused culture, which should be on everyone’s shelf, no matter how old you are. Rush to get your copy now, but remember: look right, look left, and look right again. And only cross when it is safe to do so.

Scarred for Life by Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence is available for £16.99 from lulu.com

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/scarred-for-life-how-the-pop-culture-of-the-1970s-had-such-a-lasting-effect-on-children-a7757446.html

The seventies was proliferated by public information films warning of polished floor man-traps, human sacrifice on afternoon TV and ultraviolent comics, says David Barnett

David Barnett

The Independent

Tuesday 30 May 2017

‘Scarred for Life’ is a traumatic reminder of just how scary the Seventies were for kids.

Stephen Brotherstone will be 47 next month, but every time he comes to a road he stands well back from the kerb, looks right, looks left, and looks right again, and only crosses when it is clear.

“I can’t help it,” he says. “I had the Green Cross Code burned into my head as a kid.”

Brotherstone, from Liverpool, is a child of the Seventies, and thus was educated in the ways of safety and sensibility by the public information films that proliferated in the decade. As well as knowing how to cross the road, he is fully aware that you never climb an electricity pylon to retrieve a kite, that if you put a rug on a polished floor you might as well set a man-trap, and that the fool-hardy child who plays near open water will fall victim to a hooded spirit voiced by Donald Pleasence.

“I honestly think the public information films are the last great art form waiting to be recognised,” he says. “They’re wonderful, like complete horror films distilled into 30 seconds.”

The films have a place in a new book written by Stephen and Dave Lawrence called Scarred for Life, and they are just one piece of the rather horrific puzzle that was 1970s popular culture aimed at children. Last month the Daily Mail lambasted Jeremy Corbyn for the leaked Labour manifesto that would “take us back to the 1970s”. They were thinking more about renationalisation, tax hikes and strikes though, not the relentless and often disturbing cavalcade of entertainment that left a generation ever so slightly traumatised.

We are talking the likes of TV’s Sapphire and Steel, the otherworldly agents played by David McCallum and Joanna Lumley who investigated the stuff of young nightmares – people trapped in photographs, spooky nursery rhymes. We are talking 1977’s kids’ TV series Children of the Stones, which got youngsters’ anxiety levels radged right up from the moment the wailing theme tune began. We are talking the ultraviolent Action comic, which gleefully replicated all the X-rated movies kids could not watch in comic book form, until Frank Bough ripped up a copy on TV in a righteous fury and it was pulled by the publishers. It is all in the book, and much more besides.

At more than 730 pages, this is a labour of love and a traumatic reminder of just how scary the Seventies were for kids. Put more than two 40-somethings in a room and sooner or later they’ll talk about the pop culture of their day, and how it was so often inappropriate to contemporary mores. Which is exactly how Scarred for Life came about.

Brotherstone works in the Liverpool branch of the comics-and-geek-culture chain Forbidden Planet, and one day got talking with regular customer Dave Lawrence about the TV shows of their youth. He says, “Everything we remembered seemed to be horrific and bleak in some way. As soon as I got home I started looking on the internet for books on the subject, but I was pretty amazed that although I could get books about space hoppers and glam rock, there was nothing that really looked at all this stuff from the Seventies which was massively scary.”

A colleague suggested he write one himself, which he laughed off. But when Lawrence offered to co-write and research, he thought again, and together they embarked on a three-and-a-half-year journey to document their childhood scares, which has just now borne fruit.

Brotherstone and I swap memories of shows that freaked us out. “Remember The Feathered Serpent?” he says. I did. ITV’s attempt at a historical drama for kids, set in ancient Mexico. “They had human sacrifice and all sorts at 4.30 in the afternoon!” he adds.

But what was it about the Seventies that produced such weird, eerie and horrifying stuff for kids? Brotherstone’s theory is that it was a hangover from the permissive Sixties. “At the end of that decade the shutters sort of came up and film-makers and artists started doing a lot of stuff that they felt was free of censorship,” he says. “I think they felt so free that they just went for it in a big way, there was possibly an element of naivety in what people thought was appropriate for kids. These days there are so many guidelines about what children should and shouldn’t be exposed to, and that sort of thing wasn’t in evidence much back in the Seventies, which is why we had a lot of stuff that looks really scary and disturbing today.”

Young people prepare to yawn, but it was a different world back then. We knew we should not talk to strangers or the terrifying bogeyman of “the dirty old man” (both Brotherstone and I realise that back then we assumed parents meant “tramps” rather than today’s more ubiquitous paedophile), but we still went out all day without letting our mums and dads know where we were going. We roamed the bounds of our territory, and occasionally beyond, without the safety net of a mobile phone if we needed to speak to home. We scuffed our knees and ripped our clothes and carried big sticks.

“It all didn’t do us any harm,” says Brotherstone, laughing before adding, “God, that’s such a cliche. But it feels so different today.”

One thing that has also changed is the way we consume our culture. In these days of catch-up TV, binge-watching box-sets and downloading movies, it is perhaps hard to conceive of the immediacy and transient nature of TV especially back then – which is why Brotherstone thinks we remember stuff from the Seventies with such clarity.

“These days a young person will be watching a TV show at the same time as being on their phone or doing something else; they know they don’t have to give it their full attention because they can catch up and watch it again anytime,” he says. “But in the Seventies we really, properly watched stuff. You had to. So you’d sit down in front of the TV and you’d tell everybody to be quiet and you’d concentrate, because it was your one and only chance to see the show. It wasn’t going to be repeated, we didn’t have video recorders, we couldn’t just watch it again.

‘Children of the Stones’ has been called ‘the scariest programme ever made for kids’

“And I think that’s why we remember the adverts and the public information films so clearly. We couldn’t fast-forward through the ads so we had to sit through them while we were waiting for Magpie or whatever to start again, and they just stuck in our heads.”

Scarred for Life does not just focus on horror and science fiction flavoured TV and films, though it does so lovingly and exhaustingly, but also looks at toys, sweets and light entertainment shows of the decade, for example The Black and White Minstrel Show. If you do not know what that is, it was essentially a bunch of white people wearing blackface for song and dance numbers. And no-one batted an eyelid.

One of the nice touches of the book is that it views Seventies culture not as an academic treatise, and not even with adult nostalgia, but through the lens of the children that Brotherstone and Lawrence were at the time.

“We originally intended to cover the Eighties as well,” says Brotherstone, “but it soon became apparent we would have far too much material. So we’re doing a second book, and we’ll be looking at that from the perspective of us becoming teenagers in that decade.”

While the Eighties had its share of inappropriate consumer culture, being the decade of the video nasty for example, it will also heavily focus on the Cold War that dominated and the very real threat of nuclear extinction. Brotherstone vividly recalls having his first anxiety attack – though he did not know what it was at the time – over the thought of everyone he knew and loved dying in a nuclear holocaust. “I was 13,” he says. “That’s going to come into volume two a lot, how that fear influenced culture, from the terrifying Threads to ‘99 Red Balloons’.”

But that is a work in progress, and it is book one of Scarred for Life with its sometimes quaint, sometimes paralysingly horrifying portrayal of the 1970s through its child-focused culture, which should be on everyone’s shelf, no matter how old you are. Rush to get your copy now, but remember: look right, look left, and look right again. And only cross when it is safe to do so.

Scarred for Life by Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence is available for £16.99 from lulu.com

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/scarred-for-life-how-the-pop-culture-of-the-1970s-had-such-a-lasting-effect-on-children-a7757446.html

Friday 27 March 2020

Kenny Rogers RIP

One for Lebowski lovers everywhere:

When I was (a lot) younger, there was a movie quiz for kids called Screen Test, which hold a film-making competition every year. The only winner I recall based its story on this, using the song as its soundtrack:

More 'traditional' Kenny:

And one for the road:

He was also a seriously good photographer:

The Thumb

Cove Butano Park

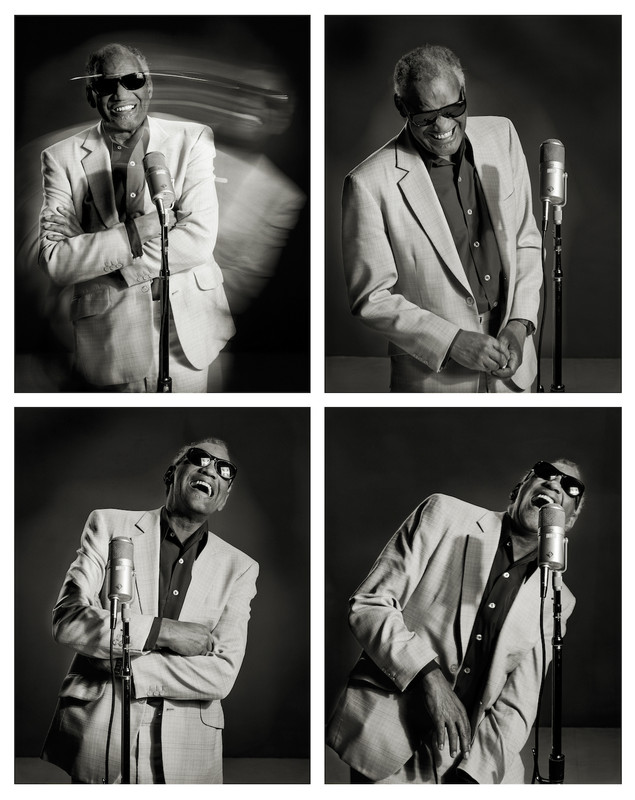

Ray Charles

One Tree

Lincoln Memorial

Wednesday 25 March 2020

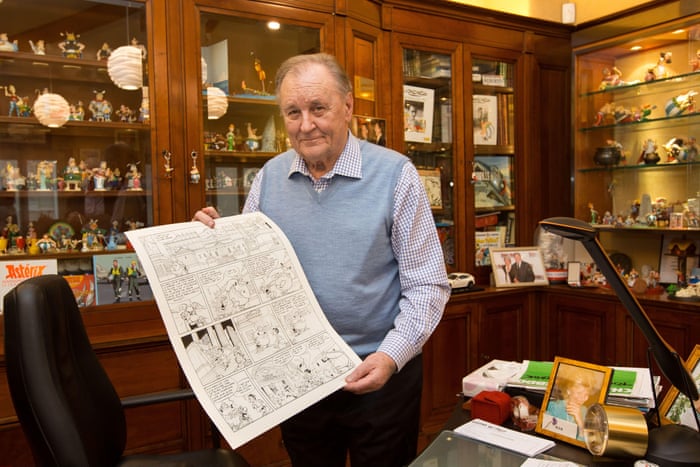

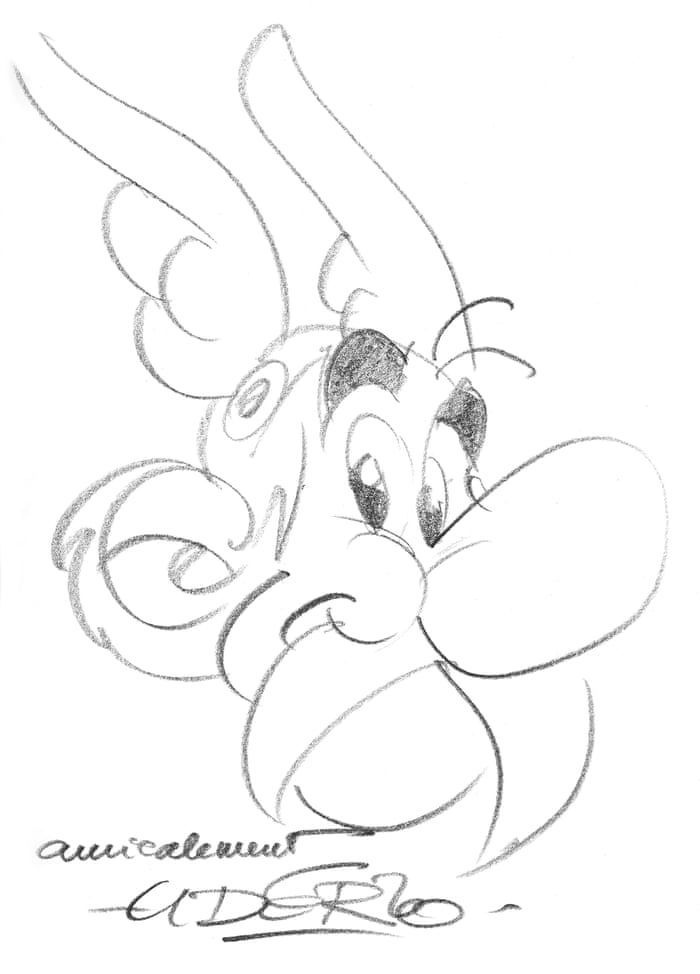

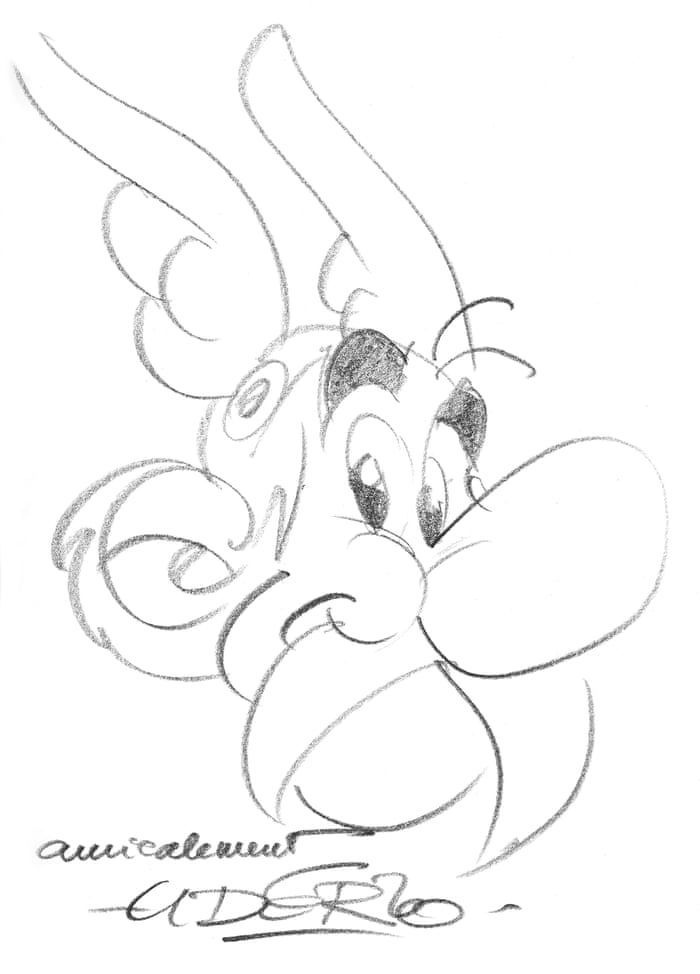

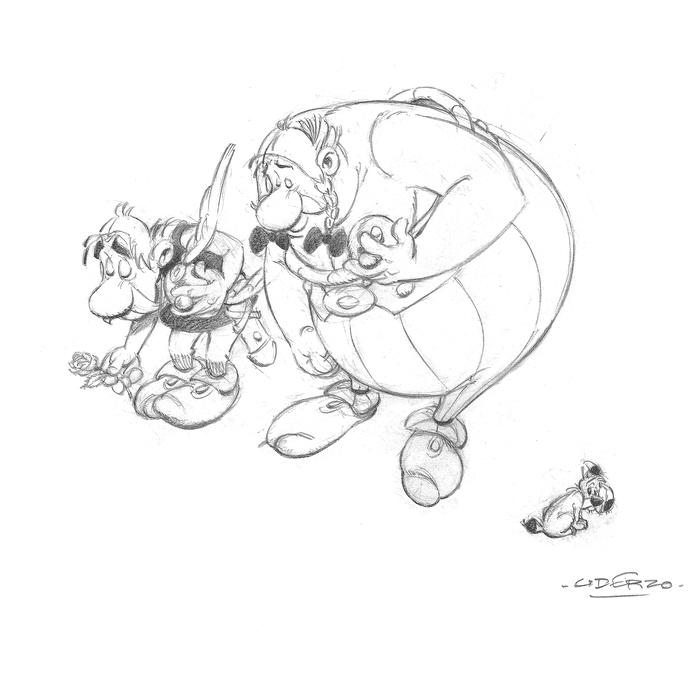

Albert Uderzo RIP

Asterix creator Albert Uderzo dies at 92

French comic-book artist, who created Asterix with the writer René Goscinny, dies at home ‘from a heart attack unrelated to the coronavirus’

Alison Flood

The Guardian

Tue 24 Mar 2020

Asterix illustrator Albert Uderzo has died at the age of 92, his family has announced.

The French comic book artist, who created the beloved Asterix comics in 1959 with the writer René Goscinny, died on Tuesday. He “died in his sleep at his home in Neuilly from a heart attack unrelated to the coronavirus. He had been very tired for several weeks,” his son-in-law Bernard de Choisy told AFP.

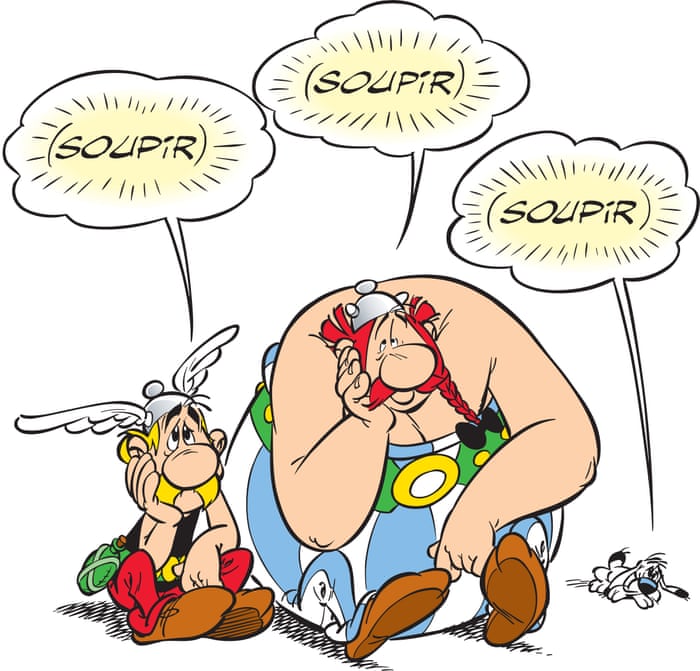

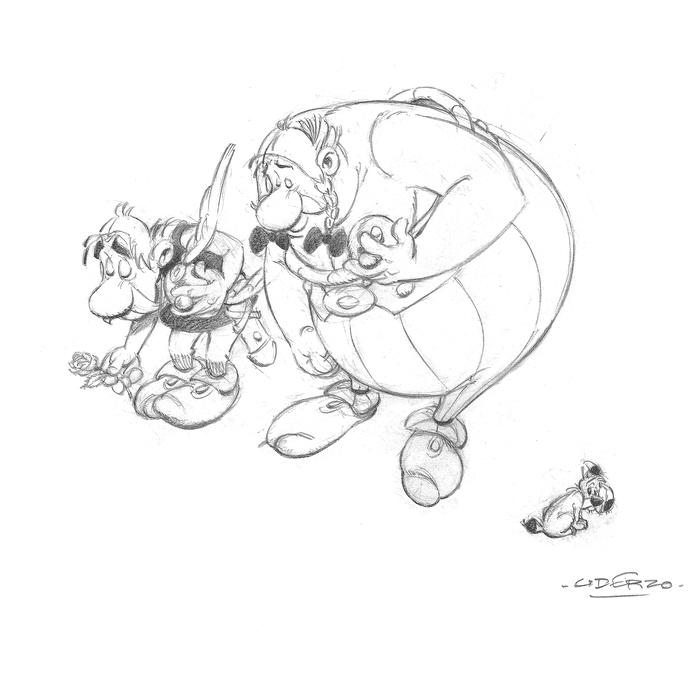

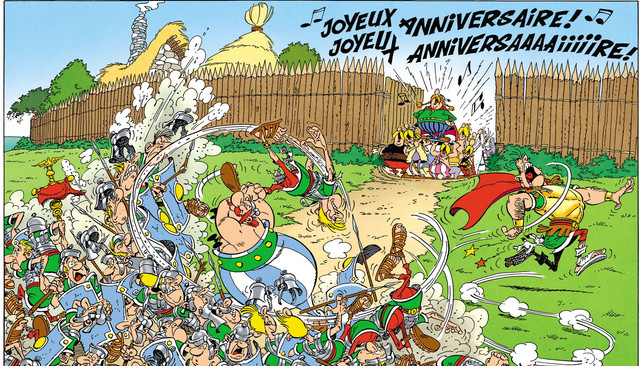

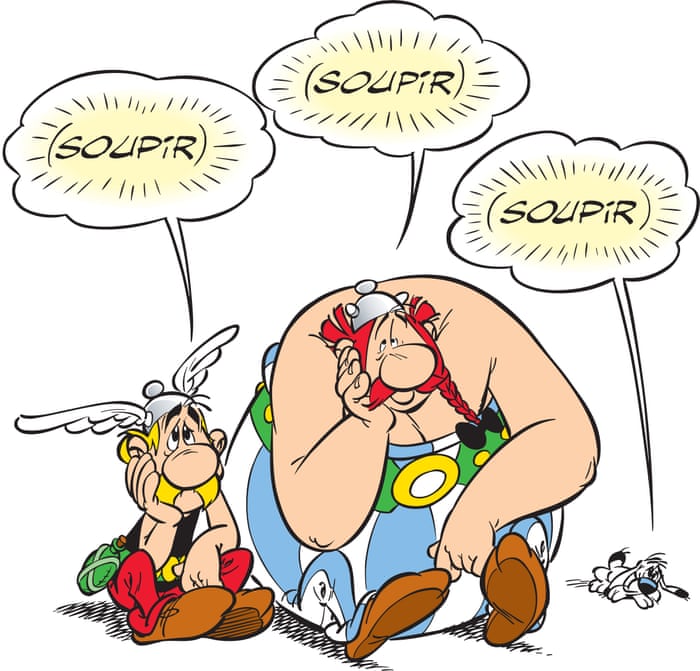

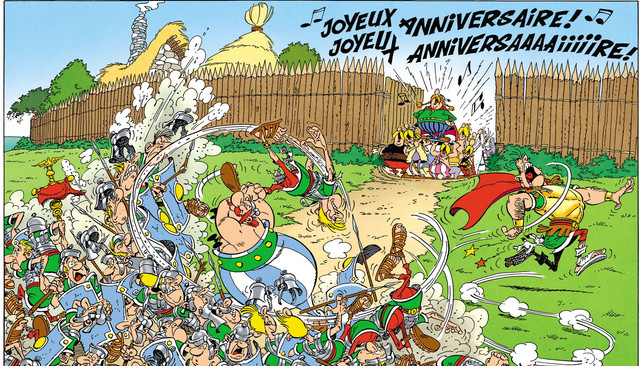

One of the best-loved characters in French popular culture, with more than 370m albums sold worldwide, 11 films and an Asterix theme park, the small-statured Asterix is a warrior from Roman-occupied ancient Gaul, who together with his best friend Obelix and dog Dogmatix – Idéfix in the French original – takes pleasure in outwitting Roman legionnaires. Fortunately for Asterix, Obelix fell into a cauldron of magic potion as a child, making him invincibly strong.

Each comic starts in the same way, before Asterix and his friends go on increasingly farflung adventures – in Asterix in Britain, he introduces tea to the ancient Britons; in Asterix and Cleopatra, Obelix knocks off the Sphinx’s nose. “The year is 50BC. Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well, not entirely … One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders. And life is not easy for the Roman legionaries who garrison the fortified camps of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium.”

Waterstones children’s laureate Cressida Cowell, author and illustrator of the How to Train Your Dragon books, said: “I loved Asterix as a child, and his style was absolutely iconic. Creating a huge cast of individually recognisable characters, and the minute detail of all those group battles and the action scenes is an achievement in itself, but his real skill was combining fast-paced adventure with such humour and warmth. Children come to reading in a lot of different ways, with comics and graphic novels being hugely important for a lot of kids. Asterix has taught generations of children around the world to love reading.”

Comedian Chris Addison was one of many fans to mourn Uderzo’s passing online. “Very few people’s work will ever give me the amount of pleasure his has ever since I was very young. One of my greatest culinary regrets is that I’ll never get to eat wild boar the way he drew them for Asterix. Chapeau, monsieur,” he said on Twitter.

Mark Millar, the creator of comics including Kingsman and Kick-Ass, called Uderzo “the Master” and “my gateway drug to beautiful European comics”, while Rafael Albuquerque, illustrator and co-creator of American Vampire, said Uderzo was “one of my biggest influences in comics”. “Asterix was the first comic I read, from my aunt’s bookshelf. With him I learnt about expression more than anyone. Merci maître!” he wrote on Twitter.

Writer Oliver Kamm, whose mother, Anthea Bell, translated the Asterix books into English, said Uderzo was “a cartoonist of genius, whose skills perfectly combined with those of the brilliant René Goscinny”. Kamm said he was deeply sad and added: “Though not an English speaker like Goscinny (a keen anglophile), Uderzo had gracious appreciation of the Asterix translations of my mother.”

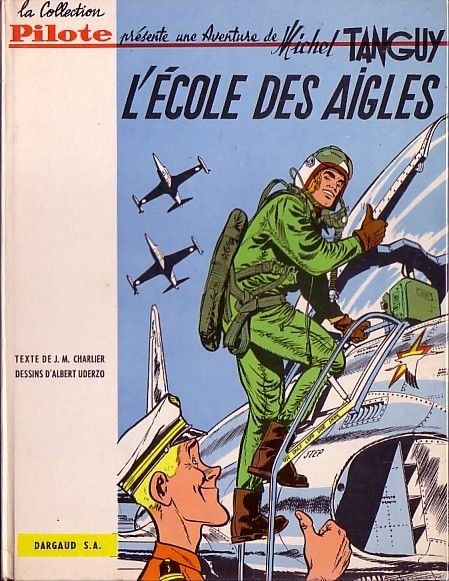

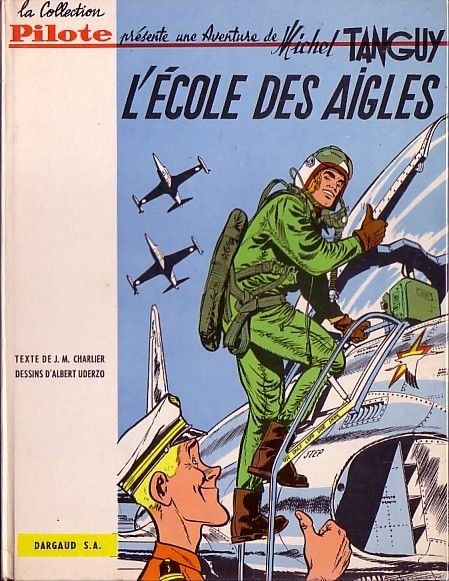

Uderzo met Goscinny in 1951, and the pair began creating characters together, including Oumpah-Pah, seen as a precursor to Asterix. In 1959, they were asked to create a magazine called Pilote, which would feature a “typically French hero”. They agreed to set their story in ancient Gaul, with the first issue published in October featuring The Adventures of Asterix the Gaul. More than 300,000 copies were sold.

Goscinny died in 1977, during an exercise stress test for a medical checkup. Uderzo continued the adventures of Asterix alone. The Great Divide, the 25th Asterix album, was published in 1980 and was the first to be written and drawn by Uderzo alone. In 2009, Uderzo retired, selling the rights to the character to Hachette.

Tue 24 Mar 2020

Asterix illustrator Albert Uderzo has died at the age of 92, his family has announced.

The French comic book artist, who created the beloved Asterix comics in 1959 with the writer René Goscinny, died on Tuesday. He “died in his sleep at his home in Neuilly from a heart attack unrelated to the coronavirus. He had been very tired for several weeks,” his son-in-law Bernard de Choisy told AFP.

One of the best-loved characters in French popular culture, with more than 370m albums sold worldwide, 11 films and an Asterix theme park, the small-statured Asterix is a warrior from Roman-occupied ancient Gaul, who together with his best friend Obelix and dog Dogmatix – Idéfix in the French original – takes pleasure in outwitting Roman legionnaires. Fortunately for Asterix, Obelix fell into a cauldron of magic potion as a child, making him invincibly strong.

Each comic starts in the same way, before Asterix and his friends go on increasingly farflung adventures – in Asterix in Britain, he introduces tea to the ancient Britons; in Asterix and Cleopatra, Obelix knocks off the Sphinx’s nose. “The year is 50BC. Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well, not entirely … One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders. And life is not easy for the Roman legionaries who garrison the fortified camps of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium.”

Waterstones children’s laureate Cressida Cowell, author and illustrator of the How to Train Your Dragon books, said: “I loved Asterix as a child, and his style was absolutely iconic. Creating a huge cast of individually recognisable characters, and the minute detail of all those group battles and the action scenes is an achievement in itself, but his real skill was combining fast-paced adventure with such humour and warmth. Children come to reading in a lot of different ways, with comics and graphic novels being hugely important for a lot of kids. Asterix has taught generations of children around the world to love reading.”

Comedian Chris Addison was one of many fans to mourn Uderzo’s passing online. “Very few people’s work will ever give me the amount of pleasure his has ever since I was very young. One of my greatest culinary regrets is that I’ll never get to eat wild boar the way he drew them for Asterix. Chapeau, monsieur,” he said on Twitter.

Mark Millar, the creator of comics including Kingsman and Kick-Ass, called Uderzo “the Master” and “my gateway drug to beautiful European comics”, while Rafael Albuquerque, illustrator and co-creator of American Vampire, said Uderzo was “one of my biggest influences in comics”. “Asterix was the first comic I read, from my aunt’s bookshelf. With him I learnt about expression more than anyone. Merci maître!” he wrote on Twitter.

Writer Oliver Kamm, whose mother, Anthea Bell, translated the Asterix books into English, said Uderzo was “a cartoonist of genius, whose skills perfectly combined with those of the brilliant René Goscinny”. Kamm said he was deeply sad and added: “Though not an English speaker like Goscinny (a keen anglophile), Uderzo had gracious appreciation of the Asterix translations of my mother.”

Uderzo met Goscinny in 1951, and the pair began creating characters together, including Oumpah-Pah, seen as a precursor to Asterix. In 1959, they were asked to create a magazine called Pilote, which would feature a “typically French hero”. They agreed to set their story in ancient Gaul, with the first issue published in October featuring The Adventures of Asterix the Gaul. More than 300,000 copies were sold.

Goscinny died in 1977, during an exercise stress test for a medical checkup. Uderzo continued the adventures of Asterix alone. The Great Divide, the 25th Asterix album, was published in 1980 and was the first to be written and drawn by Uderzo alone. In 2009, Uderzo retired, selling the rights to the character to Hachette.

Monday 23 March 2020

Saturday 21 March 2020

Wednesday 18 March 2020

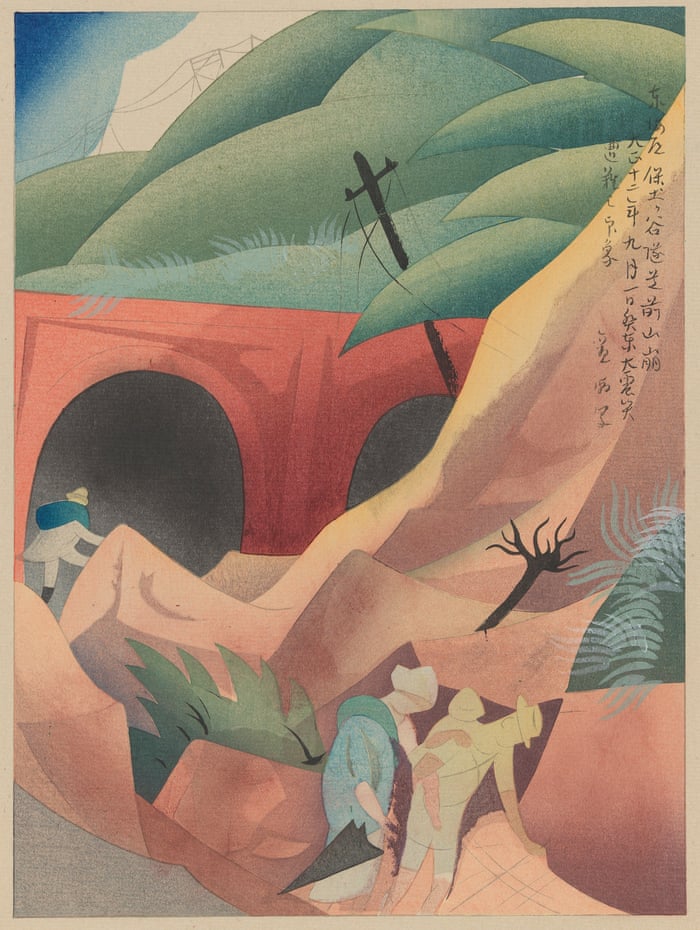

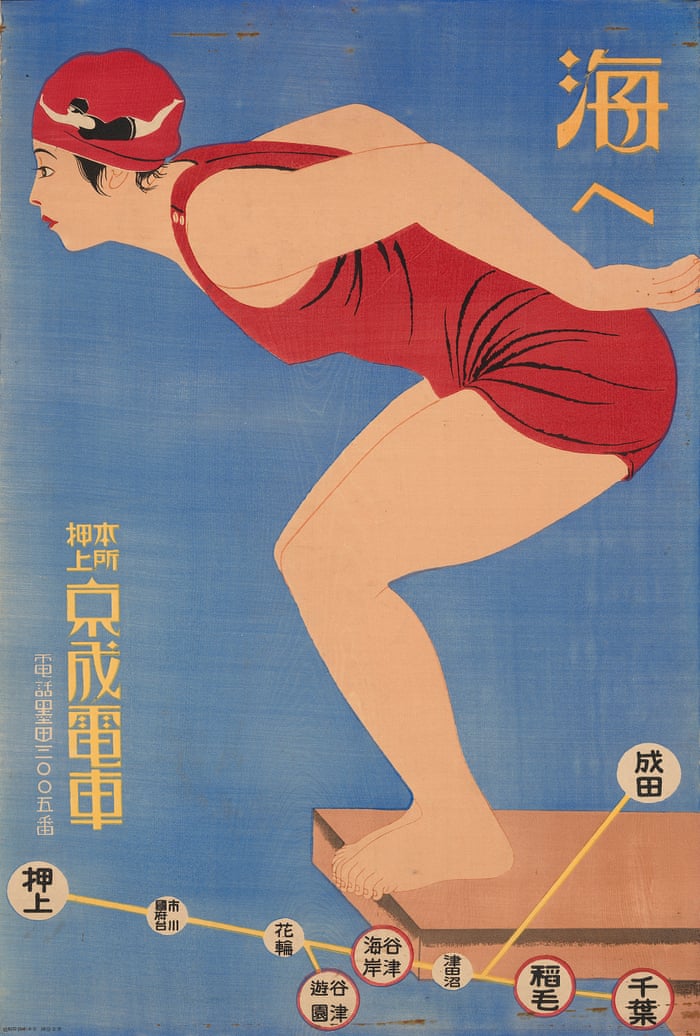

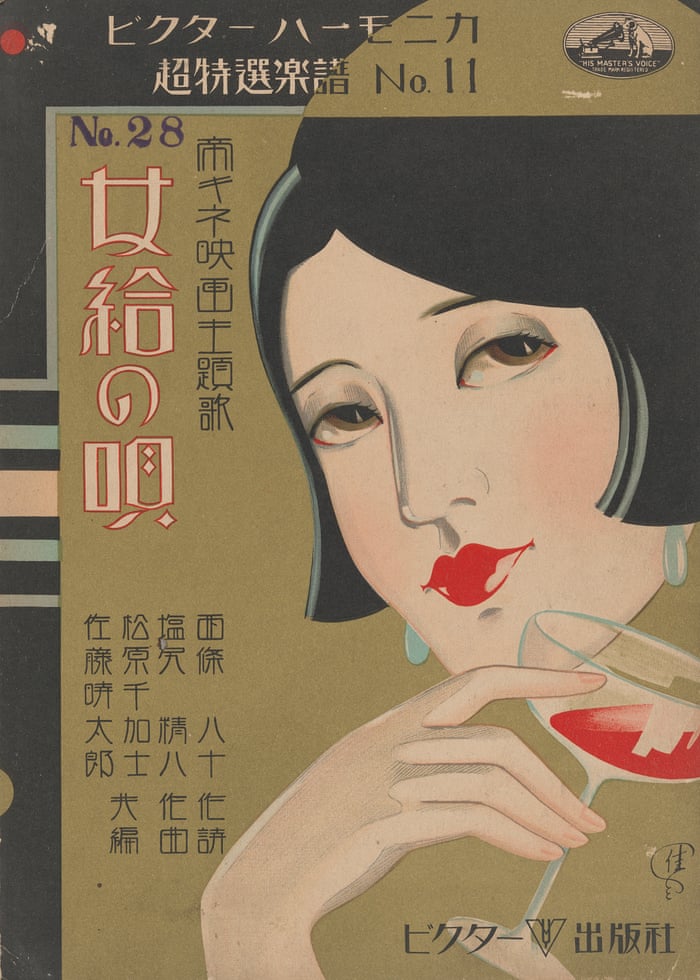

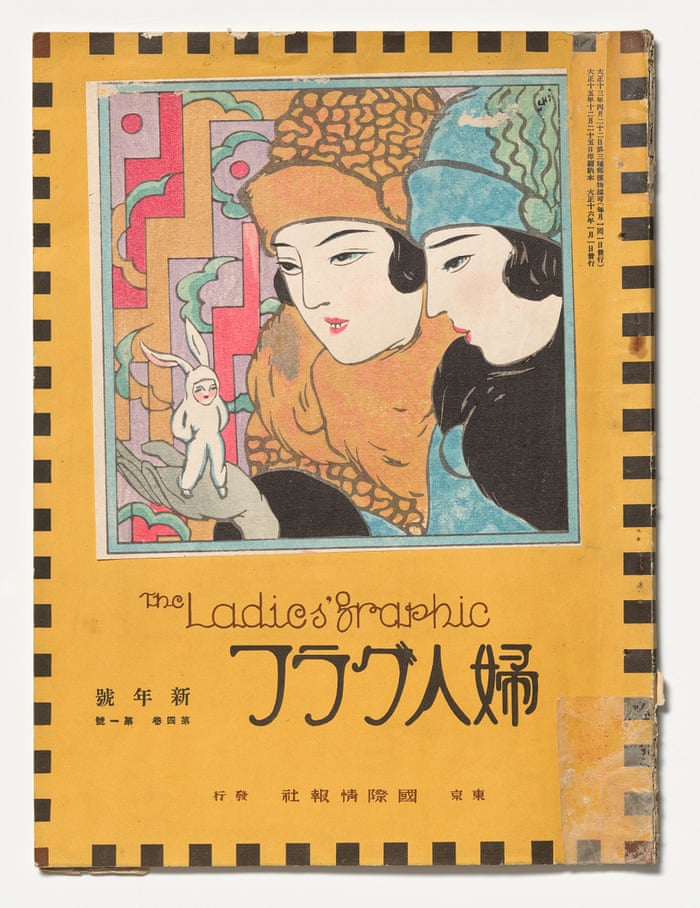

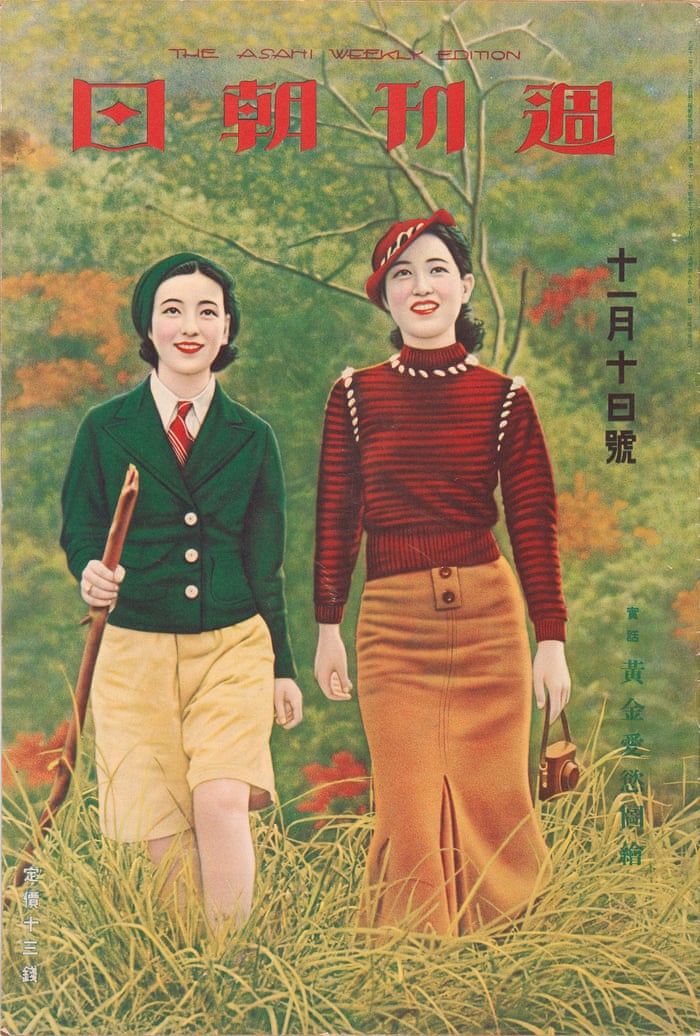

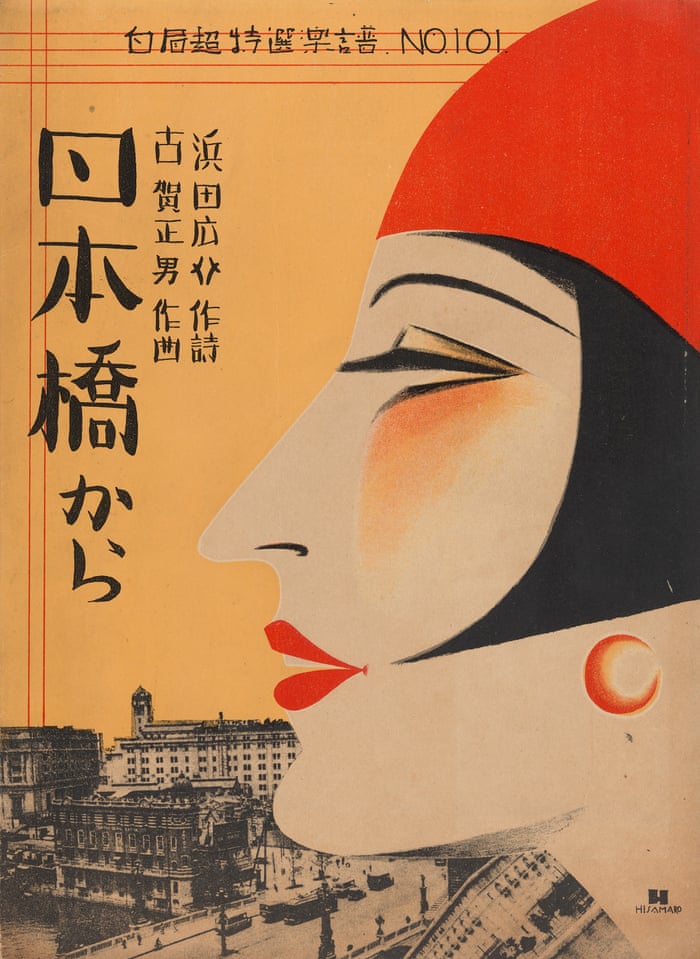

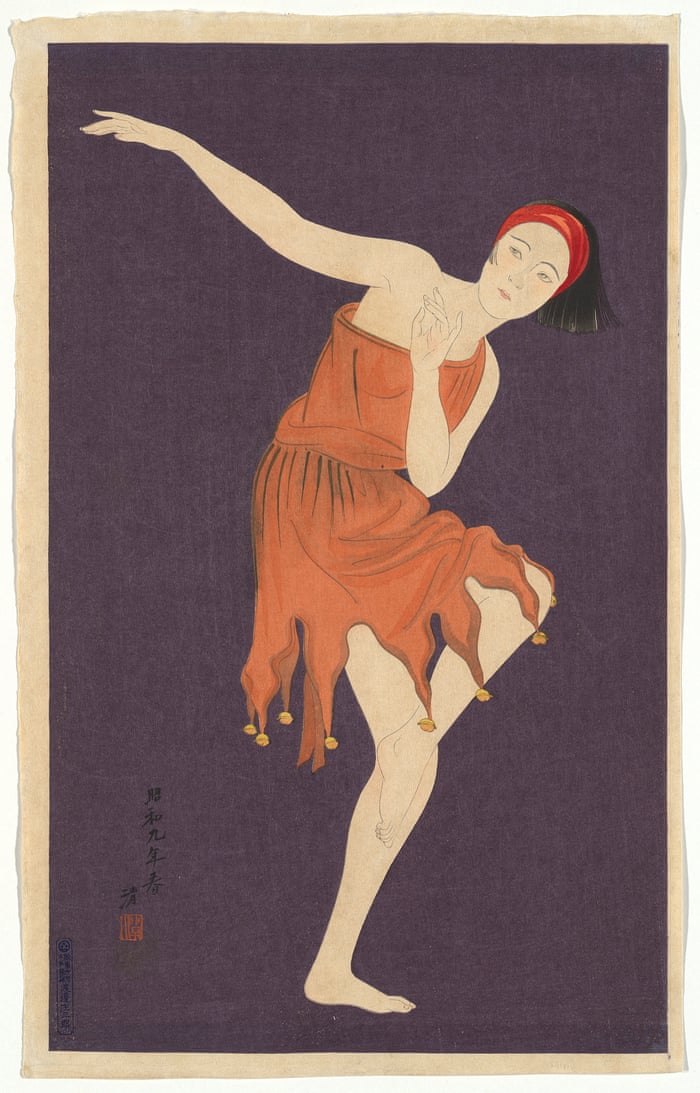

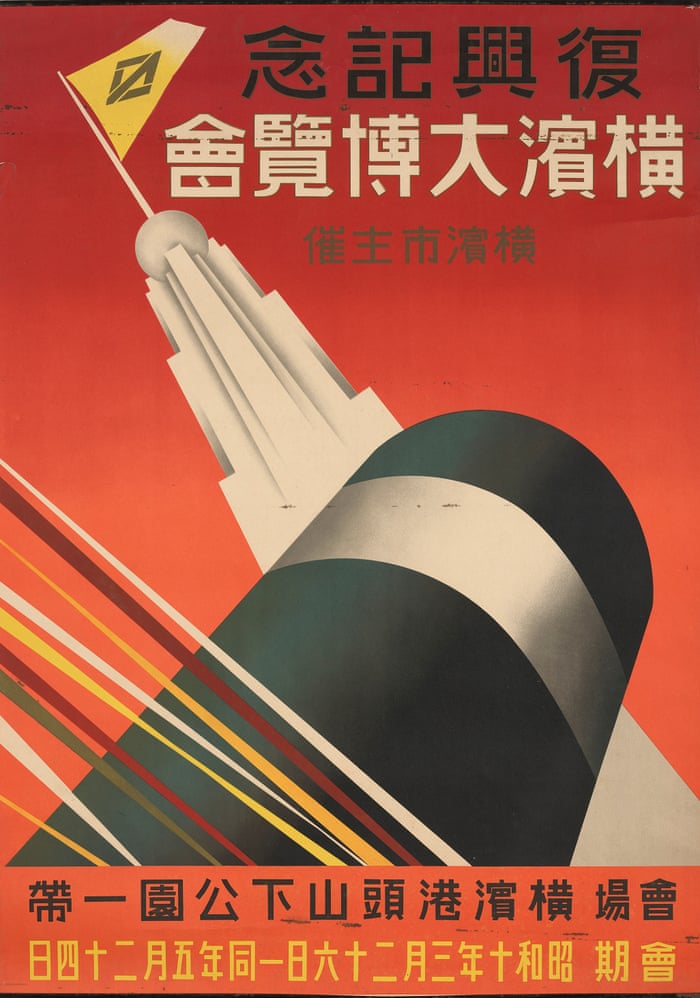

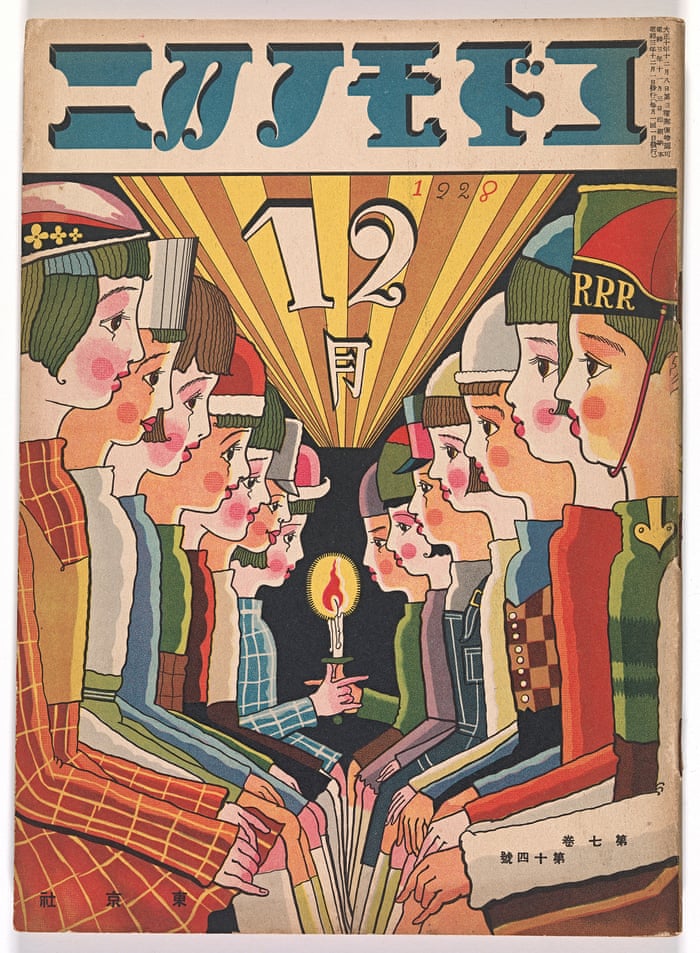

Japanese modernist graphic design

Landslide in Front of the Hodogaya Tunnel on the Tōkaidō (1924) by Oda Kanchō, colour woodblock

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)