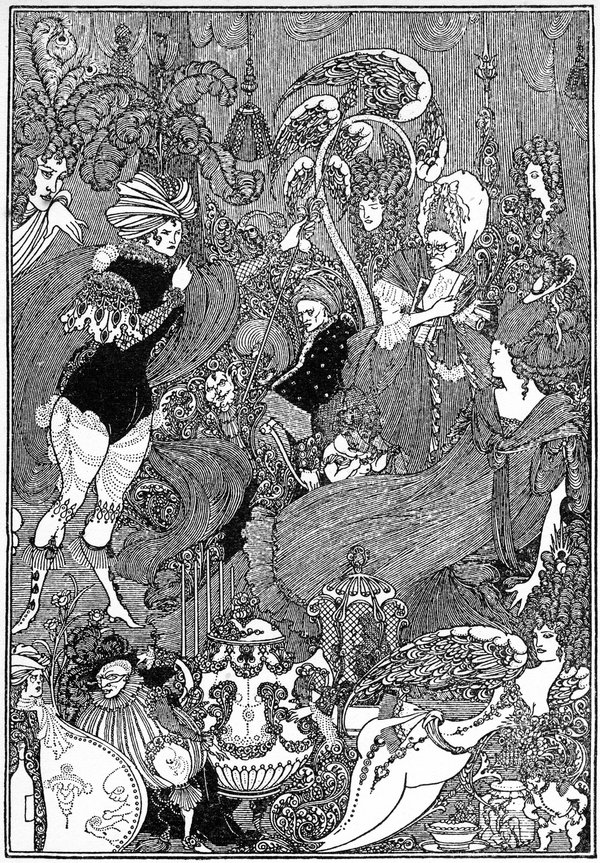

The Cave of Spleen, 1896

Too filthy to print – Aubrey Beardsley and his explosions of obscenity

His erotic ink drawings, full of nudity and sex, influenced everyone from Klimt to Picasso. But, ahead of a Tate Britain show, we look at the pictures that were deemed just too outrageous.

Jonathan Jones

The Guardian

Fri 28 Feb 2020

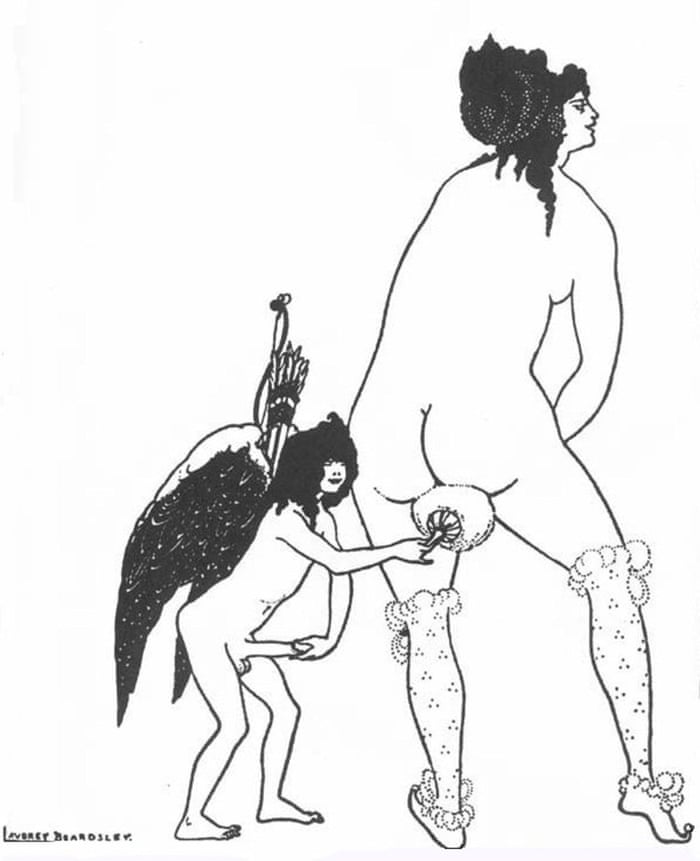

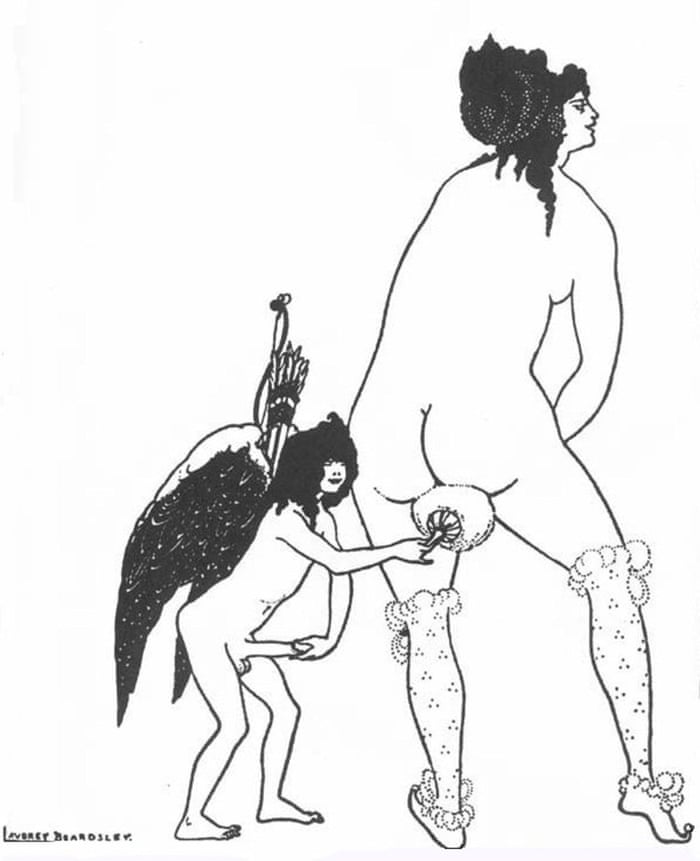

A woman who is naked except for fancy stockings touches what the artist calls her “coynte” while a winged cupid teases her bottom with a powder puff. A wizened man admires a young man’s elephantine erection, the glans as big as his bald head – all delineated in sharp black outlines and shadowed with inky pools against expanses of white. These are a few of the many explosions of obscenity that a slender, pale young man created in the room he checked into at the Spread Eagle hotel in Epsom, Surrey, in June 1896.

Fri 28 Feb 2020

A woman who is naked except for fancy stockings touches what the artist calls her “coynte” while a winged cupid teases her bottom with a powder puff. A wizened man admires a young man’s elephantine erection, the glans as big as his bald head – all delineated in sharp black outlines and shadowed with inky pools against expanses of white. These are a few of the many explosions of obscenity that a slender, pale young man created in the room he checked into at the Spread Eagle hotel in Epsom, Surrey, in June 1896.

The Toilet of Lampito, 1896

The drawings Aubrey Beardsley completed in this suburban hideaway were to illustrate the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata by Aristophanes. The works, that can be perused at your leisure in Tate Britain’s forthcoming exhibition, had an incalculable effect on the birth of modern art. Beardsley’s eroticism would soon be emulated all over Europe by revolutionaries such as Klimt, Schiele and Picasso, while James Joyce summed up his impact on modernism in a double entendre: “Kunstfull”.

That isn’t generally how this unique artist is remembered, though. Beardsley is pigeonholed as a preciously eccentric purveyor of late-Victorian erotica. Rediscovered in the 1960s, when both Victoriana and sex were fashionable, he hovers in the subconscious of British art. His name sounds posh, which adds to the air of whimsy, but he was born into an economically unstable lower-middle-class family in Brighton in 1872 and left school aged 16.

Beardsley was an insurance clerk before being discovered by Oscar Wilde’s first male lover, Robert Ross. This led to an artistic collaboration with Wilde, but his importance goes far beyond the aesthetic movement. He put sexuality at the centre of modern art for the first time, spreading his influence across Europe – to Vienna, Paris and Barcelona – 25 years before surrealism.

Then in 1895, a year before he settled in at the Spread Eagle, Beardsley’s world fell apart. Wilde was arrested and charged with gross indecency. The author’s love for Lord Alfred Douglas became a scandal and anyone associated with him was suspected of sodomy. Beardsley, at the age of 22, had been chosen by Wilde to illustrate the printed edition of his disturbing drama Salome. Following that success, he became art editor, designer and illustrator of the Yellow Book, a bestselling magazine that brought avant garde ideas into respectable homes. But when Wilde fell, its publisher John Lane sacked him. Beardsley had only recently been able to give up his day job. Now he was vilified and poverty-stricken.

The Peacock Skirt, Salomé, 1893Then in 1895, a year before he settled in at the Spread Eagle, Beardsley’s world fell apart. Wilde was arrested and charged with gross indecency. The author’s love for Lord Alfred Douglas became a scandal and anyone associated with him was suspected of sodomy. Beardsley, at the age of 22, had been chosen by Wilde to illustrate the printed edition of his disturbing drama Salome. Following that success, he became art editor, designer and illustrator of the Yellow Book, a bestselling magazine that brought avant garde ideas into respectable homes. But when Wilde fell, its publisher John Lane sacked him. Beardsley had only recently been able to give up his day job. Now he was vilified and poverty-stricken.

The poet WB Yeats, a friend of Beardsley, remembered him looking into a mirror shortly after being sacked and saying: “Yes, yes, I look like a sodomite ... but no, I am not that.” The man in the mirror was an exquisite dandy: when Beardsley became a star in 1890s London, he started wearing suits in subtly contrasting shades of grey with yellow gloves over his ethereally thin figure. Yet there is no evidence that he ever went to bed with anyone of any gender – except maybe, biographers speculate, his sister, Mabel.

And here Mabel is, naked in a back room at Tate Britain. To get a sneak peak at Beardsley’s drawings, I’ve visited the museum’s Prints and Drawings Rooms. The frontispiece he designed for the collected plays of a now-forgotten writer rests on a wooden stand. Mabel Beardsley is the nude at the far left, with layers of radiating hair that look like they belong in a psychedelic poster. She is looking ecstatically at Wilde, who stands beside her dressed as the ancient wine god Bacchus. In front of them is a goat-legged faun.

Sex is Beardsley’s theme and, unprovable allegations aside, it seems to have existed for him only on paper. That makes him an artist for our time. Long before the virtual and fluid sexualities of the 21st century, Beardsley created an erotic fantasy world of shifting identities and infinite variety. His art is one long act of self-pleasuring that reached its consummation on Epsom High Street.

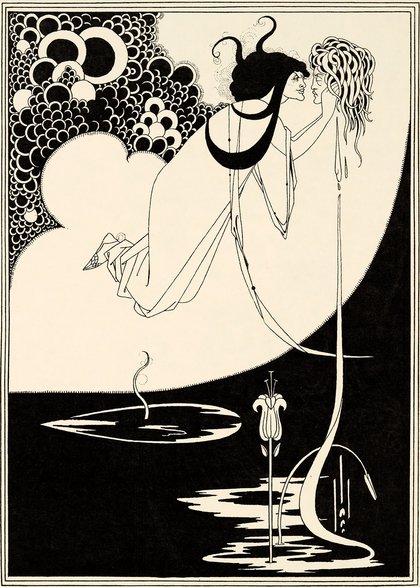

The Climax, 1893

His most famous illustration for Wilde’s Salome is actually called The Climax. In this intense symbolist design, Salome has persuaded her stepfather, Herod, to have John the Baptist’s head cut off in return for gratifying his lust with an erotic dance. She can now satiate her own lust for the Baptist – or at least his lips. She floats in the air, seemingly with orgasmic joy, as black blood pours from the fetishised dead head she embraces.

The Toilet of Salome (first version), 1894

Does that seem an over-explicit interpretation of this great fin de siècle image? Well, you should see his rejected designs for Salome. Several scenes were deemed too dirty by the publisher and he was asked to replace them with milder versions. In his original drawing of The Toilet of Salome, a pageboy stands naked holding a tray of tea things. Another near-nude youth sits with his hand between his legs, masturbating as he gazes at the tray-carrier. Meanwhile, Salome also masturbates.

The Lady with the Rose, 1897

Sex is all in the head. That is Beardsley’s message, and the basis of the strange game he played with Victorian censorship. The reason Salome first appeared in English as a book, rather than on stage, was because it was refused a licence by the Lord Chamberlain. Beardsley’s drawings mock the censor by dancing a fine line between innocence and depravity. The publisher accepted his vision of Salome’s love of a severed head, but rejected his drawing of her sitting with her back to us in a dressing gown that’s open. What was the problem? She holds a conductor’s baton.

The Yellow Book Vol I, 1894

Before he got sacked from the Yellow Book, Beardsley filled the widely read magazine with similar suggestiveness. His illustration A Night Piece shows a woman in a long black dress and gloves and a thin black ribbon round her white throat walking down a dark city street – she is, in Victorian parlance, a woman of the night. In another picture, called L'education, a young woman is listening attentively to her older friend. Both have tough, pinched faces. It’s not a sentimental but a sexual education set in a brothel.

L’Éducation Sentimentale, 1894

Beardsley pictured his audience as young women. On the cover he designed for the Yellow Book’s publicity leaflet, his imagined female reader studies the latest volumes outside a bookshop. She looks rapt, for Beardsley depicts reading itself as the most subversive of pleasures. In his revised version of The Toilet of Salome, she has Émile Zola’s novel Nana on her bookshelves – a “dirty French novel”, as Lou Reed would later put it. The Yellow Book was yellow to evoke the typical covers of sexy French fiction. Wilde wrote Salome in French, intoxicated by the writings of Flaubert, Huysmans and Baudelaire. Beardsley was equally au fait, regularly taking the boat train to Paris. French artists loved him back: Toulouse-Lautrec ordered three copies of his illustrated Salome.

When Beardsley checked in to the Spread Eagle hotel, he’d just come back from Brussels, another capital of fin de siècle culture. There he probably encountered the explicit art of Félicien Rops, including his 1878 gouache Pornocrates, in which a pig is held on a leash by a naked woman wearing a blindfold and black stockings. On the way back from the Belgian capital, Beardsley fell seriously ill. It was to get out of London’s smog that he fled to Epsom. He had known since he was diagnosed with tuberculosis when he was seven years old that his lifespan would be limited. In the two years following his stay in Epsom, he would travel to France in search of better health, dying at Menton on the Riviera in 1898, aged 25.

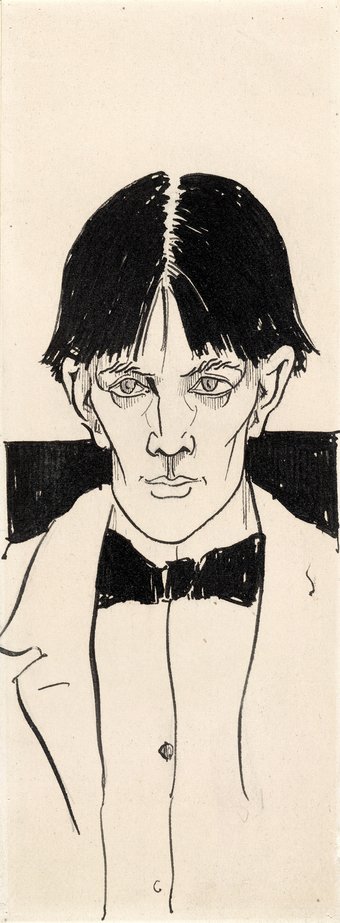

Self-Portrait, 1892

As his young life entered its premature twilight, he found sensual solace in Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, a play about love defeating death – or, in Greek, Eros defeating Thanatos. Aristophanes wrote it during a murderous war between Athens and Sparta that seemed to have no end. He imagines the women of both cities refusing to have sex with their husbands to stop the war. Beardsley turns this sex strike into an orgiastic triumph of lust over despair. Even as they listen to a speech, his Greek women can’t stop fondling each other. A Spartan woman gleefully taunts her lust-crippled husband with her body. Men gather in a mass display of monumental members.

We tend to analyse erotic art in terms of power, but for Beardsley it was quite simply a matter of life and death.

• Aubrey Beardsley is at Tate Britain, London, 4 March to 25 May.

No comments:

Post a Comment