Clive James, Literary Critic Who Took His Wit to TV, Dies at 80A transplanted Australian, he had a zest for the knockout punch as he sparred with all things cultural, creating a pungent comic persona on British television.

By William Grimes

of the New York Times...

27 November 2019

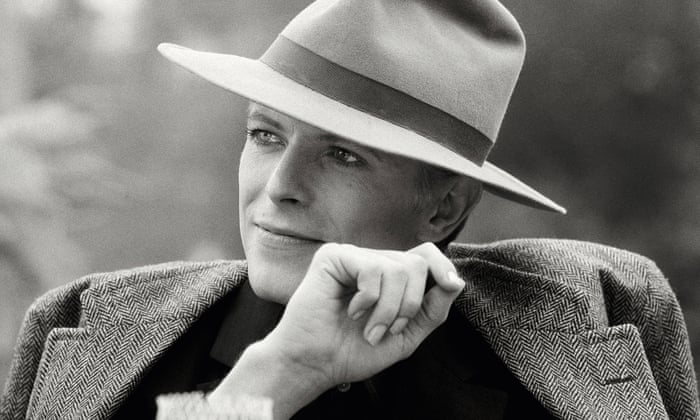

Clive James, a transplanted Australian whose wit and aphoristic style made him a fixture in Britain as a literary critic of unusually wide range, a longtime television writer for The Observer and a reliable comic presence on numerous television shows, notably “Clive James on Television,” died on Sunday in Cambridge, England. He was 80.

His literary agents confirmed the death in a statement posted on Twitter on Wednesday. In 2010, Mr. James learned he had leukemia, kidney failure and emphysema.

Mr. James shared with his Australian compatriot Robert Hughes a pithy, muscular prose style and a zest for landing the knockout punch, the key to his success as The Observer’s television critic from 1972 to 1982.

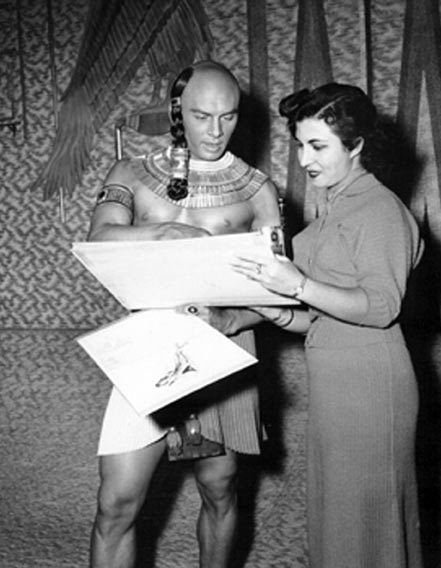

He once dismissed a tedious public affairs program as “the mental equivalent of navel fluff.” He described William Shatner’s acting technique in “Star Trek” as “picked up from someone who once worked with somebody who knew Lee Strasberg’s sister.”

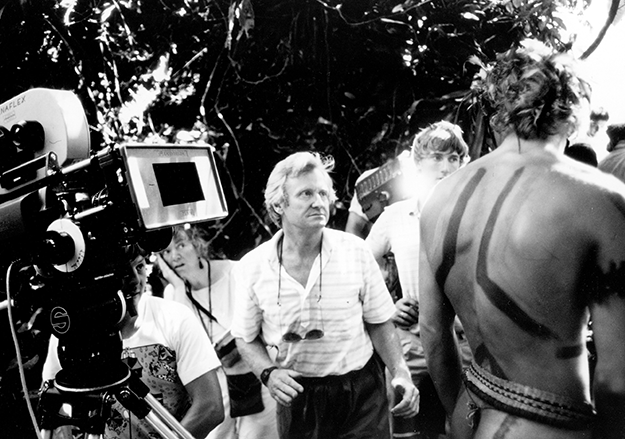

Unlike his British counterparts, who tended to sneer at popular programming, Mr. James regarded the entirety of television as precious raw material waiting to be mined. He found the peculiar language of sports commentators and Barbara Woodhouse’s dog-training show just as fascinating as a plush historical drama from the BBC. The Observer column, Mr. James wrote in “The Blaze of Obscurity” (2009), the fifth installment of his memoirs, was “the real backbone of my career as a writer.”

That career was varied. He published several volumes of poetry, including a series of mock epics and, as a lyricist, collaborated with the singer-songwriter Pete Atkin on six albums. He wrote a handful of novels, including “Brilliant Creatures” and “The Remake,” sendups of the London literary world.

Most of his non-television writing, however, was devoted to literary criticism, some of which appeared in American publications like The New Yorker, The Atlantic and The New York Review of Books.

His catholic tastes, and his enthusiasm for learning new languages, led him to take on figures as various as Edmund Wilson, Raymond Chandler and Primo Levi.

His range was on full display in “Cultural Amnesia” (2007), in which he profiled more than a hundred representative 20th-century figures, most of them literary, arranged alphabetically from Anna Akhmatova to Stefan Zweig.

Among other things, the book was a conscious attempt by Mr. James to re-stake his claim as a serious literary critic, which, in his own mind at least, had been damaged by his reputation as a television personality.

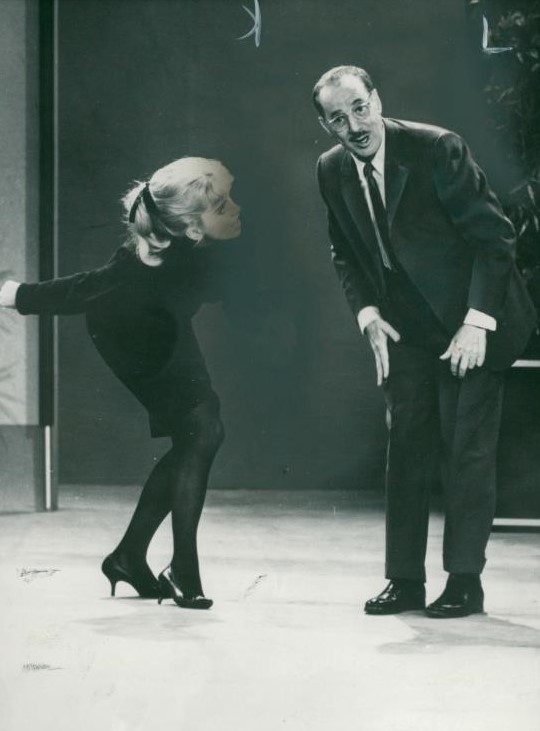

His gift for the one-liner and his lightning-fast footwork turned him into a one-man franchise. “Clive James on Television,” a quirky review of strange foreign television shows and advertisements, made him a household name and led to several sequels, as well as the travel series “Clive James’ Postcard” and a regular spot as a host of the weekly news review “The Late Show.” American viewers saw him in 1993 when PBS picked up his eight-part series “Fame in the 20th Century.”

Success came at a price. In “The Blaze of Obscurity,” he wrote: “The effect on my literary reputation was immediate. It was thoroughly compromised, and even now, after a quarter of a century, it has only just begun to recover.”

Vivian Leopold James was born on Oct. 7, 1939, in Kogarah, a suburb of Sydney, Australia. His father was taken prisoner by the Japanese at the beginning of World War II and died when the American transport plane carrying him back to Australia crashed into Manila Bay.

The elder Mr. James’s only son was named in honor of Vivian McGrath, an Australian tennis champion, but the name became untenable when “Gone With the Wind” made Vivien Leigh an international star shortly afterward. Allowed to choose a replacement, Vivian settled on Clive.

After graduating from the University of Sydney and working briefly as an assistant editor on The Sydney Morning Herald, Mr. James set sail for London in 1962.

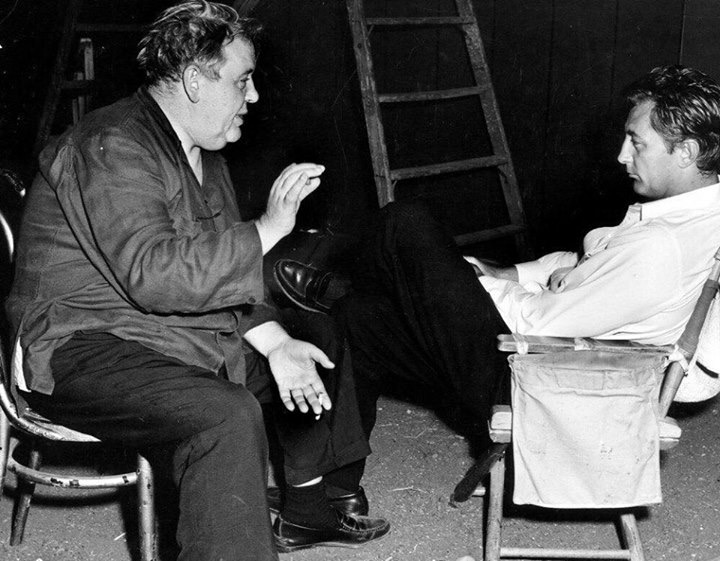

The first volume of his autobiography, “Unreliable Memoirs,” which was published in 1980 and rose to the top of the best-seller list in Britain, described his childhood in Australia. Its sequel, “Falling Towards England,” covered, in often painful detail, his mostly unsuccessful attempts to gain traction in London, where he shared a flat with the future filmmaker Bruce Beresford.

Pembroke College, Cambridge, came to the rescue, offering him a place. Mr. James did manage to earn a degree and even embarked on a doctoral dissertation (never completed) on Shelley, but the real value of his second crack at higher education was the opportunity to do anything and everything. Cambridge was, he wrote in “May Week Was in June,” his third volume of memoirs, “the one place where I could be everything I wanted to be all at once.”

Eric Idle, the future Monty Python star, welcomed him into Footlights, the student theatrical troupe; he became its president. He pressed his poems on every journal available and parlayed his enthusiasm for Hollywood potboilers and arcane Japanese directors into a position as the film critic for The Cambridge Review. Looking back in “May Week Was in June,” he wrote: “I was tireless. I was tiresome. I was omniscient. I was a pain in the arse.”

A scrambling career in literary journalism followed, recounted in “North Face of Soho.” He was perhaps the least recognized name in the constellation of young stars that included Martin Amis, James Fenton and Christopher Hitchens, although it was he, he wrote in “North Face of Soho,” who created the weekly lunch that became the London equivalent of the Algonquin Round Table.

His essays were first collected in “The Metropolitan Critic” (1974). Later collections included “At the Pillars of Hercules” (1977) and “From the Land of Shadows” (1982). His television criticism, issued in book form in “Visions Before Midnight” (1977), “The Crystal Bucket” (1981) and “Glued to the Box” (1983), was gathered in a single volume, “On Television,” in 1991.

Mr. James, who lived in London and Cambridge, is survived by his wife, the Dante scholar Prue Shaw, and their two daughters, Claerwen and Lucinda. In 2012, he and his wife separated after Leanne Edelsten, an Australian socialite and former model, revealed on Australian television that she and Mr. James had carried on an affair for eight years.

Mr. James continued to write and publish poetry, much of it valedictory. “Japanese Maple,” a poignant meditation on his impending death, ran in The New Yorker in September 2014 and appeared in the collection “Sentenced to Life: Poems” (2015).

The New Statesman published two others in August of that year, including “The Emperor’s Last Words,” in which he contemplates, among other things, Napoleon, a niece’s ambitions to be a writer and his own mortality, writing: “It’s time to go. High time to go. High time.”

He never lost his enthusiasm for television, which he reviewed weekly for The Daily Telegraph from 2011 until May 2014. This time around, he turned a somewhat kindlier eye on topics as various as the Eurovision Song Contest, the Royal Jubilee and Barry Manilow, whom he had once savaged but was now prepared to appreciate.

“What you’re hearing from me now is atonement,” he wrote. “Time has happened to me, and as the dark closes in I am trying to behave better.”

In May, he told an audience at a literary festival in London, “One of my ambitions, at this age and in this condition, short of breath and perhaps not long for this world, is to live until Box 4 of ‘Game of Thrones.’”

Japanese MapleYour death, near now, is of an easy sort.

So slow a fading out brings no real pain.

Breath growing short

Is just uncomfortable. You feel the drain

Of energy, but thought and sight remain:

Enhanced, in fact. When did you ever see

So much sweet beauty as when fine rain falls

On that small tree

And saturates your brick back garden walls,

So many Amber Rooms and mirror halls?

Ever more lavish as the dusk descends

This glistening illuminates the air.

It never ends.

Whenever the rain comes it will be there,

Beyond my time, but now I take my share.

My daughter’s choice, the maple tree is new.

Come autumn and its leaves will turn to flame.

What I must do

Is live to see that.That will end the game

For me, though life continues all the same:

Filling the double doors to bathe my eyes,

A final flood of colors will live on

As my mind dies,

Burned by my vision of a world that shone

So brightly at the last, and then was gone.

© Clive James, 2014