The New York Times

7 July 2018

Steve Ditko, a comic-book artist best known for his role in creating Spider-Man, one of the most successful superhero properties ever, was found dead on June 29 at his home in Manhattan, the police said on Friday. He was 90.

The death was confirmed by Officer George Tsourovakas, a spokesman for the New York Police Department. No further details were immediately available.

Mr. Ditko, along with the artist Jack Kirby and the writer and editor Stan Lee, was a central player in the 1960s cultural phenomenon known as Marvel Comics, whose characters today are ubiquitous in films, television shows and merchandise.

Though Mr. Ditko had a hand in the early development of other signature Marvel characters — especially the sorcerer Dr. Strange — Spider-Man was his definitive character, and for many fans he was Spider-Man’s definitive interpreter.

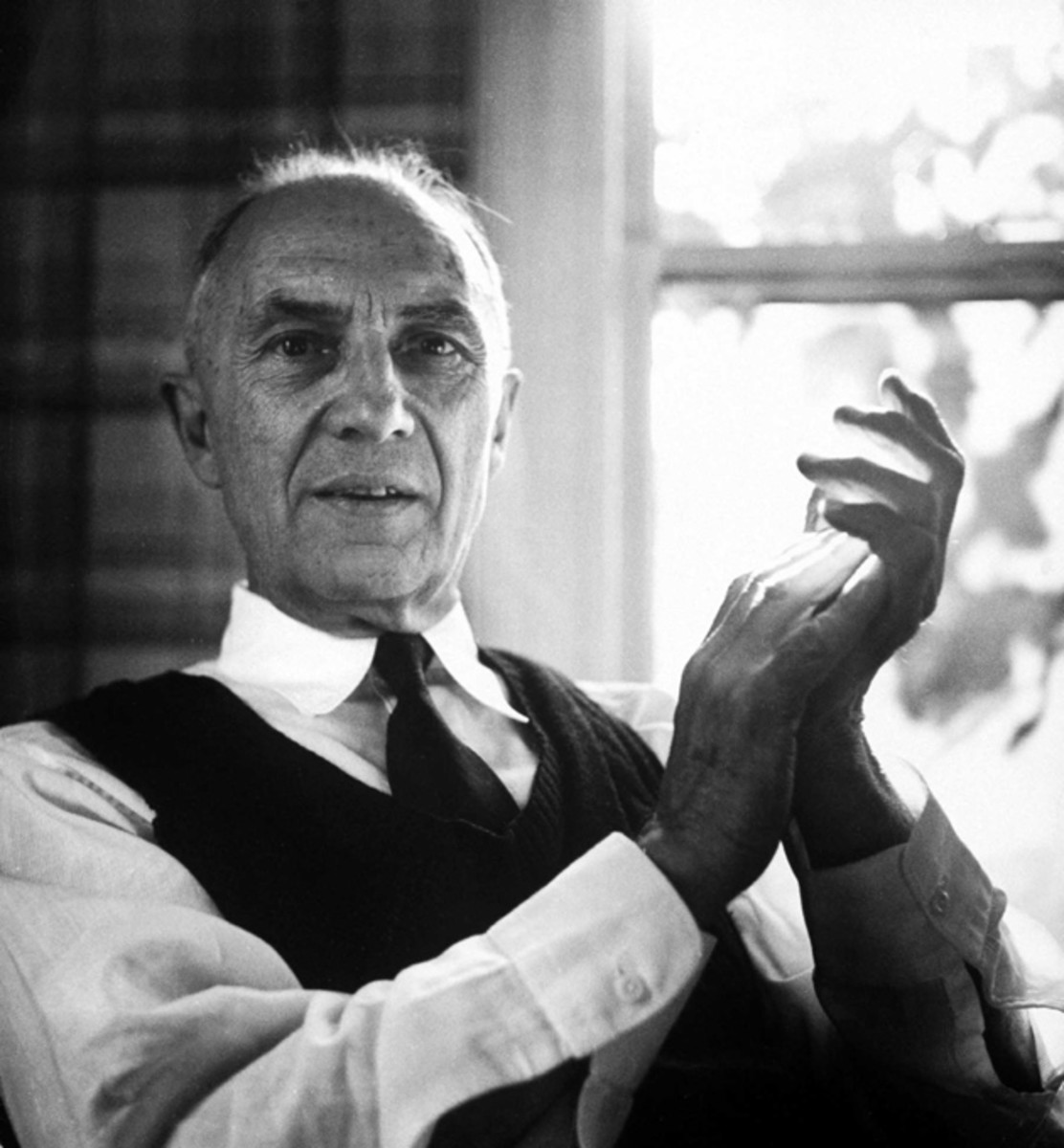

Mr. Ditko was noted for his cinematic storytelling, his occasional flights into almost psychedelic abstraction, and the philosophical convictions that often colored his work. Scrupulously private, he had a mystique rare among industry superstars.

The initial visual conception of Spider-Man did not come from Mr. Ditko. According to Blake Bell’s book “Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko” (2008), that image came from Mr. Kirby, who penciled an origin story for the Marvel title Amazing Fantasy in 1962.

When Mr. Lee, Marvel’s editor, assigned Mr. Ditko to ink it, Mr. Ditko noticed similarities between Spider-Man and the Fly — a Kirby creation for Marvel’s competitor Harvey Comics from 1959 — and raised his concerns with Mr. Lee.

Kirby’s take was rejected, and the character’s origin was revamped to eliminate those similarities. (Out went a magic ring, among other elements.) Mr. Lee gave Mr. Ditko a synopsis to flesh out.

Mr. Ditko ran with the character. Spider-Man made his debut that year in Amazing Fantasy No. 15, and the character’s popularity led to his own title, The Amazing Spider-Man, which Mr. Ditko penciled, inked and largely plotted from 1963 to 1966.

Unlike Superman or Batman (characters from Marvel’s chief rival at the time, National Periodical Publications, which later became DC Comics), Spider-Man had humanizing flaws. He was hounded, not praised, by the press and the police. In his secret identity as Peter Parker, he was mocked by his peers. And he struggled with guilt over his uncle’s death, which he felt he could have prevented, and fretted about his aging aunt.

Mr. Ditko also helped conceive famous villains, like the Green Goblin and Dr. Octopus, and supporting characters.

Spider-Man’s fight scenes and aerial acrobatics had a spry kineticism that contrasted with the brawny physicality of Kirby’s compositions. Spider-Man, unlike the thunder god Thor and other signature Kirby characters, was not musclebound; he was a slender teenager. While Mr. Lee’s dialogue for Spider-Man could be buoyant, peppered with wisecracks, Mr. Ditko lent mood.

Spider-Man’s mask, obscuring his entire face, and his web-textured costume had a slightly morbid aspect. Spider-Man’s pensive moments — when Peter agonized over sacrifices his alter ego had demanded of him, for example — echoed the psychological struggles in Mr. Ditko’s earlier horror comics.

Stephen Ditko was born on Nov. 2, 1927, in Johnstown, Pa. His father, also Stephen, was a steel-mill carpenter; his mother, Anna, was a homemaker. His father bequeathed to his son a love of newspaper strips like Hal Foster’s “Prince Valiant,” and the young Stephen devoured Batman and Will Eisner’s noirish Sunday newspaper insert, “The Spirit.”

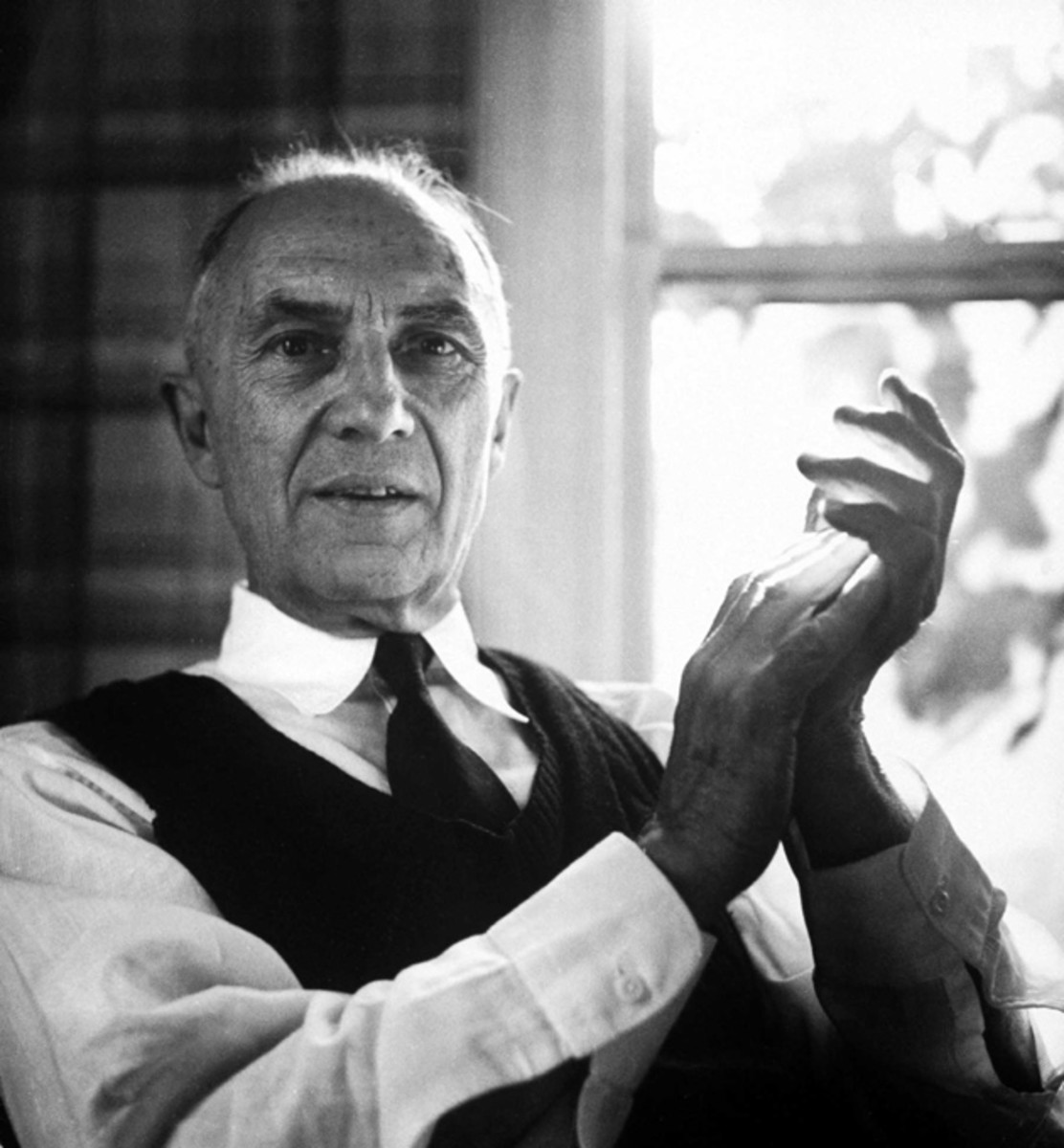

After graduating from high school in 1945, Mr. Ditko joined the Army and was stationed in Germany, where he drew cartoons for a service newspaper. In 1950, under the G.I. Bill, he attended the Cartoonist and Illustrator School (which later became the School of Visual Arts) in New York.

Mr. Ditko’s first work in print was in early 1953, in a romance comic from a minor publisher. For three months he worked in the studio of Kirby and Joe Simon, the creators of Captain America, before heading to Charlton Comics, which had its headquarters in Derby, Conn. Charlton offered low pay and inferior production values but creative freedom, and Mr. Ditko would return there often over his career.

The introduction of the Comics Code Authority — a regulating body established by the industry in 1954 in response to Senate subcommittee hearings into the supposed influence of comics on juvenile delinquency — stifled Mr. Ditko’s Charlton output, which had largely covered horror, crime and science fiction.

Influenced by the artist Mort Meskin, a specialist in mood and noirish textures, Mr. Ditko had infused his pre-Charlton work with a sweaty anxiety and recurrent motifs of paranoia. In “In Search of Steve Ditko” — a 2007 British documentary narrated by the TV personality Jonathan Ross— the novelist and comic book writer Alan Moore says that in Mr. Ditko’s work there was “a tormented elegance to the way the characters stood, the way that they bent their hands.”

He added, “They always looked as if they were on the edge of some kind of revelation or breakdown.”

In 1954, tuberculosis forced Mr. Ditko back to Pennsylvania, where he nearly died. After a year, he returned to New York, where he approached Mr. Lee, at the time a writer-editor for Atlas Comics, a precursor to Marvel.

Mr. Lee, impressed with Mr. Ditko’s speed and proficiency, hired him. Atlas’s horror line, emasculated by the code, became largely divided between Kirby’s stories, starring generic monsters with names like Groot and Fin Fang Foom, and Mr. Ditko’s agonized character studies.

Cutbacks at Atlas brought Mr. Ditko back to Charlton, where he and the writer Joe Gill created the nuclear-powered Captain Atom, before returning to what was now the Marvel Comics Group. Marvel was in a rebirth, starting with the publication of The Fantastic Four in 1961, and continuing with Thor and the Hulk.

Spider-Man appeared in 1962. Kirby drew the cover of his debut, but for three years the character was Mr. Ditko’s baby.

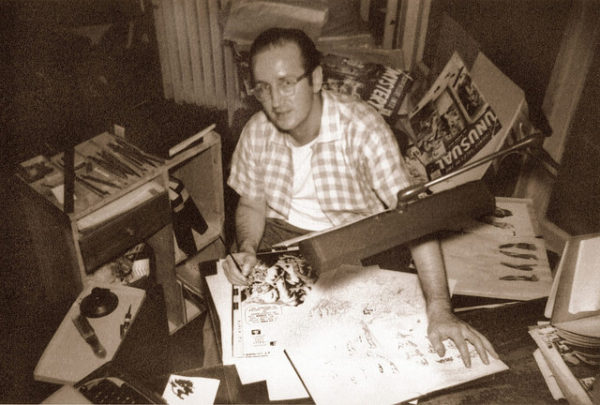

Mr. Ditko helped develop other Marvel superheroes, including Iron Man and the Hulk. Of these, probably his best-known, besides Spider-Man, was Dr. Strange, a “master of the mystic arts,” who first appeared in 1963.

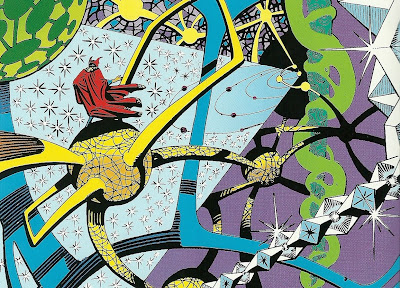

For Dr. Strange’s occult adventures and battles in alternate dimensions, Mr. Ditko created foreboding expanses of abstract shapes and patterns, ruled by evil sorcerers and supernatural entities.

But it was with Spider-Man that Mr. Ditko flourished. Marvel artists generally followed the “Marvel method,” in which artists built on Mr. Lee’s synopses and were encouraged to emulate Mr. Kirby’s outsize style.

Mr. Ditko, who focused less on fight scenes and more on Peter Parker’s psyche, had broad license with plotting and drawing “The Amazing Spider-Man.” Many fans regard Issues 31, 32 and 33 — which climax with the superhero, after reviewing his life, triumphantly upending heavy machinery that has pinned him — as a Ditko peak.

Mr. Ditko’s conception of the series had been shifting, increasingly influenced by Ayn Rand’s libertarian philosophy. Spider-Man’s villain the Looter was named after Rand’s term for those leeching from the creative elite, phrases like “equal value trade” crept into Parker’s words, and he voiced resentment toward student protesters. (Mr. Lee, in speaking engagements on college campuses, found himself in the awkward position of having to explain to irate young audiences that such a stance was Mr. Ditko’s, not his own.)

Mr. Ditko bristled at being denied royalties when Spider-Man had his own animated ABC television series and was used in product tie-ins. He left Marvel in 1965 (Spider-Man No. 38 was his final issue) and worked for other publishers before returning to Charlton.

Mr. Ditko pursued Randian notions further, particularly with Mr. A, a character he created for Witzend, a black-and-white comic aimed at adults and unconstrained by the Comics Code. Mr. A, attired in a white suit and conservative hat, was named after “A is A,” the idea in Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged” that there is one unassailable truth, one reality, and only white (good) and black (evil) forces in society. Unlike mainstream superheroes, he killed criminals.

For Charlton, Mr. Ditko created the Question, also in a suit and hat but devoid of facial features. Like Mr. A, the Question spoke in a stilted, didactic vernacular akin to a philosophical tract’s. (Like Captain Atom, the Question is now owned by DC.) In 1968, Mr. Ditko said in a rare interview that the Question and Mr. A were his favorite creations.

In 1968 Mr. Ditko joined DC, where he created the Hawk and the Dove, superpowered brothers of opposing moral dispositions, and the Creeper, a crime fighter with a maniacal laugh. Another bout with tuberculosis derailed those series, and both ended within a year.

Mr. Ditko’s aversion to attending comic conventions and meeting fans was well known. Early unauthorized reproductions of his work in fanzines angered him, as did the failure by some fanzine publishers to return originals he had lent them. By 1964 Mr. Ditko had withdrawn from the public eye, limiting exchanges to mail or telephone. His reclusiveness, and his Randian ideas, lent his work a patina of mystery.

The 1970s and ’80s proved comparatively fallow. Mr. Ditko’s output plummeted, especially after Charlton’s demise in 1978. In the 1980s, there were more stints at Marvel and DC and at the independent publisher Eclipse. However, in 1991, Mr. Ditko co-created Squirrel Girl for Marvel, who remains a fan favorite.

In later years, Mr. Ditko created black-and-white digest-size comics financed with Kickstarter funds and sold online. These self-published titles, ad-free and often edited by Robin Snyder, bore a scratchy, sometimes pointillistic style and Randian preoccupations: rationality, “looters,” “earners.”

There was no immediate information about survivors.

Mr. Ditko was inducted into the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1990 and the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 1994. In Sam Raimi’s Hollywood feature “Spider-Man,” in 2002, the opening credits read, “Based on the Marvel comic book by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko.” The 2008-9 ABC animated series “The Spectacular Spider-Man” gave similar credit.

In 2016, the Casal Solleric museum in Mallorca, Spain, presented a retrospective of his work, “Ditko Unleashed.” That same year, Marvel Studios released the hit film adaptation “Doctor Strange”; an opening credit read, “Based on the characters created by Steve Ditko.”

Mr. Ditko avoided his fans to the end. In 2014, Dan Greenfield, a writer for the website 13th Dimension, recounted reaching Mr. Ditko’s Manhattan apartment doorway in an attempt to interview him. Mr. Ditko did not bite.