At The Habit, York: -

Bouquet Of Roses

Hold Back The Tears

With Ron away there was no Elderly Brothers set this week. The place was full for most of the night until just after 11pm when it thinned out rather unexpectedly. One or two players who had brought friends all left to catch last buses I guess. The audience were very attentive and keen to join in with songs they knew. Regular Tony got them singing along with The Boxer and Deb with Hard Times. Taxi driver Chris who usually sings acapella was accompanied by our host and got everyone singing Dock Of The Bay, Let's Stay Together and a sublime Summertime. As everyone was having such a great time I introduced my set as "two of the most miserable songs" I could have chosen and assured folks that things would improve when I'd finished. Shortly afterwards I was stunned when a stone-wall George Jones lookalike walked in - it would have made a great FNBs moment, but I doubt anyone else in The Habit noticed. After the open mic finished someone asked if anyone knew Harvest Moon, it appeared we had some late-coming Neil fans in the house! There followed a run through most of Zuma and excerpts from Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, After The Gold Rush, Harvest and On The Beach with vocal and instrumental support from audience and players alike. I do enjoy a full-on Neil session.

Friday 28 July 2017

Thursday 27 July 2017

The Station East, Gateshead - Tuesday night's set list

At the Station East, Gateshead: -

Out Of The Blue

The Road That You're Travellin'

Once An Angel

Never Let Her Slip Away

Albuquerque

You're Sixty*

Tell Me Why

I Don't Want To Talk About It

Only Love Can Break Your Heart

Things We Said Today

Returning to the Station East for another night of open mic fun, about a dozen or so punters and players filled the back room. The 2 hosts held the floor for the first hour, including an unexpected and very creditable attempt at Layla.

To much amusement, I introduced You're Sixty* by explaining how unseemly it would be of me to sing Johnny Burnette's classic with the original lyric You're Sixteen!!

The photo was taken at last week's event and recently posted courtesy of Jason Toward Photography.

Wednesday 26 July 2017

The Long Road from Jarrow by Stuart Maconie - review

In retracing the steps of the Jarrow march of 1936, Stuart Maconie finds that much of the past remains with us

Rachel Reeves

The Guardian

Monday 24 July 2017

“Our people shall not be starved … If we cannot do this, what use are we as a Labour party?’ asked Jarrow’s MP, Ellen Wilkinson, at the Labour party conference in October 1936. To make her speech she had dashed to the conference in Edinburgh from the route of the Jarrow Crusade, an event that has “stitched itself into the warp and weft of British history”, as Stuart Maconie elegantly puts it. Jarrow, an industrial town on the south bank of the Tyne, had seen the closure of its steelworks and shipyard, leaving 80% of its population unemployed. Wilkinson helped organise a march of 200 men from Jarrow to London, to present a petition to parliament demanding jobs.

The question Wilkinson posed encapsulates the thrust of Maconie’s Long Road from Jarrow, a social commentary reflecting on the parallels between the 1930s and today, as he retraces the steps of the marchers. His book is an exercise in giving the mundane its beautiful due, to use John Updike’s phrase.

Walking for most of the journey, Maconie traverses the contours of A-roads and rambling countryside from north to south, meeting a wide range of people along the way. He speaks to a restless waiter in a Ferryhill curry house about his “feeling that there must be something more, something else out there”, who has an urge “to see a bit of the world”, but resolves: “I suppose I’ll stay here.” He talks to a member of the Darlington Women’s Institute, who as a little girl in 1936 became convinced that a tent peg she found in a field belonged to the marchers. In Wakefield, he reflects on the role of religion in establishing communities as he receives the generous hospitality of the Sikh Gurdwara. And in Bedford, he learns of the family history of a pizzeria waiter in “the little Italian provincial town”, formed by a wave of immigration during the 1950s.

The book is a celebration of a certain kind of approach to politics – one of sympathy and personal connection with working-class people – which was championed by one of the first women in parliament, Ellen Wilkinson. She was a passionate feminist and socialist committed to the Labour party and to advancing the position of the working classes. Earning the nickname “Red Ellen” owing to both her politics and her flaming red hair, by 1936 she had become one of the most famous women in the country.

As Maconie’s book attests, the question posed by Wilkinson in 1936 is just as relevant for Labour now as it was then. In 1936, economic depression, unemployment and hunger were everywhere. One of the marchers was witnessed packing the ham from a sandwich he had been given into an envelope to send back home for his wife and children, who hadn’t eaten meat in weeks. Today, while unemployment levels are low, we live in a society in which work does not guarantee the absence of poverty, with a sharp rise in self-employment and zero-hour contracts; under austerity, the number of people going to food banks has soared with the Trussell Trust giving out more than a million food parcels last year. As Maconie writes: “The 30s in some ways start to look very much like Britain today, once you’ve wiped away the soot and coaldust.”

Maconie argues that class is still the defining division of British society. He also reflects upon the north-south divide as he travels from the ex-industrial northern towns of Jarrow, Ferryhill (“a mining town with no pit”) and Barnsley, to the southern market towns and suburbs of Market Harborough and Edgware. With London receiving £5,000 more per head of capital investment than the north-east, it is no wonder that marginalised northern communities voted predominantly to leave the EU in 2016. In the aftermath of the closure of the mines and the emasculation of the trade unions by Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, once cohesive communities have been dissolved and fractionalised. Wilkinson saw the impact that this dislocation had on Jarrow in 1936 and you can see it today in many towns across northern Britain. Mining communities in their heyday cultivated social bonds and a sense of intimacy that have since been eroded. Maconie recalls that in a conversation with a group of ex-miners, one of them could still remember the pit number of every single one of his fellow workers.

In 1936, Labour was so anxious to dissociate itself from what it considered to be communist hunger marches that it condemned the Jarrow Crusade. Two years earlier Ramsay McDonald, then leader of the National government, had urged Wilkinson to look at the bigger picture: “Ellen, why don’t you go and preach socialism, which is the only remedy for this?” Wilkinson viewed such a response as “sham sympathy”, devoid of human feeling and connection with the very people who sustained the life force of the Labour party. Yet simultaneously, she recognised that the poverty of her own constituency was part of a bigger picture that demanded urgent reform: “Jarrow’s plight is not a local problem … it is the symptom of a national evil.” The personal was political.

When Wilkinson and the rain-battered marchers arrived in London after 26 days on the road to present their petition to parliament, the Conservative prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, refused to meet them. Wilkinson was grief-stricken by the abandonment of her constituents by parliament and her party, and was seen “sobbing broken-heartedly” in a quiet street near Westminster.

The last survivor of the Jarrow march, Con Shiels, who died in 2012, said it “had made not one hap’orth of difference” and had been a waste of time. It may not have been a political victory, but it was a personal one; it re-established social bonds between people – the marchers and their communities at home. When Wilkinson returned to Jarrow, she was greeted by waves of cheering and triumphant crowds. As someone Maconie spoke to in a pub in Ferryhill recognised: “It achieved something in that we’re talking to you about it now.” And in talking about it by walking in their footsteps, by viewing the march through the filter of “the roads, tracks, streets and riverbanks they walked … the pews, pubs, cafes, and halls they visited”, Maconie’s book is not only a heartfelt tribute to Wilkinson and the marchers, but a reaffirmation of the role of the personal within the political, and a rallying call for anyone stirred by the story of Jarrow.

• Long Road from Jarrow: A Journey Through Britain Then and Now by Stuart Maconie is published by Ebury (£16.99).

Monday 24 July 2017

“Our people shall not be starved … If we cannot do this, what use are we as a Labour party?’ asked Jarrow’s MP, Ellen Wilkinson, at the Labour party conference in October 1936. To make her speech she had dashed to the conference in Edinburgh from the route of the Jarrow Crusade, an event that has “stitched itself into the warp and weft of British history”, as Stuart Maconie elegantly puts it. Jarrow, an industrial town on the south bank of the Tyne, had seen the closure of its steelworks and shipyard, leaving 80% of its population unemployed. Wilkinson helped organise a march of 200 men from Jarrow to London, to present a petition to parliament demanding jobs.

The question Wilkinson posed encapsulates the thrust of Maconie’s Long Road from Jarrow, a social commentary reflecting on the parallels between the 1930s and today, as he retraces the steps of the marchers. His book is an exercise in giving the mundane its beautiful due, to use John Updike’s phrase.

Walking for most of the journey, Maconie traverses the contours of A-roads and rambling countryside from north to south, meeting a wide range of people along the way. He speaks to a restless waiter in a Ferryhill curry house about his “feeling that there must be something more, something else out there”, who has an urge “to see a bit of the world”, but resolves: “I suppose I’ll stay here.” He talks to a member of the Darlington Women’s Institute, who as a little girl in 1936 became convinced that a tent peg she found in a field belonged to the marchers. In Wakefield, he reflects on the role of religion in establishing communities as he receives the generous hospitality of the Sikh Gurdwara. And in Bedford, he learns of the family history of a pizzeria waiter in “the little Italian provincial town”, formed by a wave of immigration during the 1950s.

The book is a celebration of a certain kind of approach to politics – one of sympathy and personal connection with working-class people – which was championed by one of the first women in parliament, Ellen Wilkinson. She was a passionate feminist and socialist committed to the Labour party and to advancing the position of the working classes. Earning the nickname “Red Ellen” owing to both her politics and her flaming red hair, by 1936 she had become one of the most famous women in the country.

As Maconie’s book attests, the question posed by Wilkinson in 1936 is just as relevant for Labour now as it was then. In 1936, economic depression, unemployment and hunger were everywhere. One of the marchers was witnessed packing the ham from a sandwich he had been given into an envelope to send back home for his wife and children, who hadn’t eaten meat in weeks. Today, while unemployment levels are low, we live in a society in which work does not guarantee the absence of poverty, with a sharp rise in self-employment and zero-hour contracts; under austerity, the number of people going to food banks has soared with the Trussell Trust giving out more than a million food parcels last year. As Maconie writes: “The 30s in some ways start to look very much like Britain today, once you’ve wiped away the soot and coaldust.”

Maconie argues that class is still the defining division of British society. He also reflects upon the north-south divide as he travels from the ex-industrial northern towns of Jarrow, Ferryhill (“a mining town with no pit”) and Barnsley, to the southern market towns and suburbs of Market Harborough and Edgware. With London receiving £5,000 more per head of capital investment than the north-east, it is no wonder that marginalised northern communities voted predominantly to leave the EU in 2016. In the aftermath of the closure of the mines and the emasculation of the trade unions by Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, once cohesive communities have been dissolved and fractionalised. Wilkinson saw the impact that this dislocation had on Jarrow in 1936 and you can see it today in many towns across northern Britain. Mining communities in their heyday cultivated social bonds and a sense of intimacy that have since been eroded. Maconie recalls that in a conversation with a group of ex-miners, one of them could still remember the pit number of every single one of his fellow workers.

In 1936, Labour was so anxious to dissociate itself from what it considered to be communist hunger marches that it condemned the Jarrow Crusade. Two years earlier Ramsay McDonald, then leader of the National government, had urged Wilkinson to look at the bigger picture: “Ellen, why don’t you go and preach socialism, which is the only remedy for this?” Wilkinson viewed such a response as “sham sympathy”, devoid of human feeling and connection with the very people who sustained the life force of the Labour party. Yet simultaneously, she recognised that the poverty of her own constituency was part of a bigger picture that demanded urgent reform: “Jarrow’s plight is not a local problem … it is the symptom of a national evil.” The personal was political.

When Wilkinson and the rain-battered marchers arrived in London after 26 days on the road to present their petition to parliament, the Conservative prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, refused to meet them. Wilkinson was grief-stricken by the abandonment of her constituents by parliament and her party, and was seen “sobbing broken-heartedly” in a quiet street near Westminster.

The last survivor of the Jarrow march, Con Shiels, who died in 2012, said it “had made not one hap’orth of difference” and had been a waste of time. It may not have been a political victory, but it was a personal one; it re-established social bonds between people – the marchers and their communities at home. When Wilkinson returned to Jarrow, she was greeted by waves of cheering and triumphant crowds. As someone Maconie spoke to in a pub in Ferryhill recognised: “It achieved something in that we’re talking to you about it now.” And in talking about it by walking in their footsteps, by viewing the march through the filter of “the roads, tracks, streets and riverbanks they walked … the pews, pubs, cafes, and halls they visited”, Maconie’s book is not only a heartfelt tribute to Wilkinson and the marchers, but a reaffirmation of the role of the personal within the political, and a rallying call for anyone stirred by the story of Jarrow.

• Long Road from Jarrow: A Journey Through Britain Then and Now by Stuart Maconie is published by Ebury (£16.99).

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jul/24/stuart-maconie-long-road-from-jarrow-journey-britain-then-now-review?CMP=share_btn_link

Maconie will be talking about his book at The Sage, Gateshead on Sunday 11 February, 2018:

http://www.sagegateshead.com/event/stuart-maconie-jarrow-road/

Maconie will be talking about his book at The Sage, Gateshead on Sunday 11 February, 2018:

http://www.sagegateshead.com/event/stuart-maconie-jarrow-road/

Tuesday 25 July 2017

John Heard RIP

John Heard Obituary

Frank Black

25 July 2017

John Heard, who has been found dead in a hotel room after back surgery, is probably best known for his roles as the father in the Home Alone movies and as Tom Hank's adult rival in Big. In more recent years, his on-screen appearances have become marginalised, mixing 'guest star' roles in serviceable television shows like CSI Miami and The Chicago Code with awful cinemtaic fare like Sharknado.

A look at his whole career, however, reveals an extremely talented actor, initially on stage in controversial plays like Streamers and G R Point, before moving into film with Joan Micklin Silver's excellent Boston underground newspaper drama, Between the Lines in 1977. He played Jack Kerouac opposite Sissy Spacek and Nick Nolte in Heart Beat and followed it with one of his best roles as the obsessed alcoholic Vietnam veteran Alex Cutter in Ivan Passer's conspiracy noir, Cutter's Way, alongside Jeff Bridges; this was a film so imbued with the intelligence and ideals of late 60s - mid 70s American cinema that it comes as a shock to realise it was released in 1981. The studio originally wanted Richard Dreyfuss for the role and - allegedly - Passer went to see him as Iago in the Shakespeare in the Park production of Othello, but he was more impressed with Heard's portrayal of Cassio. The roles that followed varied from those obviously targeting box office success, like Big, to more mature fare, such as his excellent cameo as the mysterious bar owner in Martin Scorsese's underrated After Hours and Robert Redford's take on John Nichols' magic realist novel, The Milagro Beanfield War.

In latter years, good roles in good films were few and far between, but he was remarkable in Bernt Amadeus Capra's Mindwalk, a daring philosophical three-hander that is, in essence, a conversation about potential and perspectives on various social and political issues facing the world.

He had a long career in television too, from guest-starring in shows like The Equaliser to meatier roles such as Abe North in Dennis Potter's less than wonderful 1985 adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's Tender is the Night for the BBC, where his performance was head and shoulders above anyone else's. His best role in recent years was surely as, Vin Makazian, the detective who was Tony's informant in The Sopranos - before he committed suicide during a bout of depression.

In 2008, he told 411Mania.com, "I think I had my time. I dropped the ball, as my father would say. I think I could have done more with my career than I did, and I sort of got sidetracked. But that's OK, that's all right, that's the way it is. No sour grapes. I mean, I don't have any regrets. Except that I could have played some bigger parts."

Monday 24 July 2017

Sunday 23 July 2017

Saturday 22 July 2017

Friday 21 July 2017

Wednesday night's set lists

At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

Just My Imagination

The River

Da Elderly: -

You've Got A Friend

I Don't Want To Talk About It

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Price Of Love

All My Loving

I'm Into Something Good

I'll Get You

Mailman Bring Me No More Blues

Another fun night at The Habit open mic with plenty of players and a constant turnover of punters, the last hour being extremely busy. Regular players entertained us with superb renditions of seldom-heard tunes: Deb with Christine McVie's Songbird and Dave with CSN's Marrakesh Express. A young chap pitched up with a ukulele and brought the house down with his 2-song set: a medley of Scottish fiddle tunes and an amazing Honey Pie (from The Beatles White Album). The Elderly Brothers dug out a couple of tunes which we haven't played for a while by The Beatles and Herman's Hermits. An unplugged session followed for the final hour with several punters joining in. As always, a most enjoyable night.

Ron Elderly: -

Just My Imagination

The River

Da Elderly: -

You've Got A Friend

I Don't Want To Talk About It

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Price Of Love

All My Loving

I'm Into Something Good

I'll Get You

Mailman Bring Me No More Blues

Another fun night at The Habit open mic with plenty of players and a constant turnover of punters, the last hour being extremely busy. Regular players entertained us with superb renditions of seldom-heard tunes: Deb with Christine McVie's Songbird and Dave with CSN's Marrakesh Express. A young chap pitched up with a ukulele and brought the house down with his 2-song set: a medley of Scottish fiddle tunes and an amazing Honey Pie (from The Beatles White Album). The Elderly Brothers dug out a couple of tunes which we haven't played for a while by The Beatles and Herman's Hermits. An unplugged session followed for the final hour with several punters joining in. As always, a most enjoyable night.

Thursday 20 July 2017

The Station East, Gateshead - Tuesday night's set list

I'm Just a Loser

Into The Light

Love Song

In The Morning Light

Is It Only The Moonlight?

A new venue and a new open mic night. In the back room of the bar the acoustics are, well, boomy to say the least, but everyone coped admirably. The majority of players were, I think, from The Sage music school and some fine skills were on show. There was even a saxophonist who accompanied one or two of the players. At about 10:15 some of the 'lads' from the Cumberland Arms arrived and an unplugged jam session ensued. A fun night!!

Wednesday 19 July 2017

Tuesday 18 July 2017

Martin Landau RIP

A great actor who grew into his gravitas: Martin Landau remembered

After making his mark on TV, the actor came into his own in his later years, with remarkable performances in Ed Wood and Crimes and MisdemeanorsPeter Bradshaw

The Guardian

Monday 17 July 2017

Martin Landau was the handsome, intelligent, reflective actor who was respected for first-class work in the theatre, and for his consistency and professionalism in films and TV in the 60s and 70s. But he gloriously came into his own in movies in his later years. Landau grew into his gravitas, and also into bittersweet human comedy and tragedy, in ways that were unavailable to him as a younger man. Landau was destined to be the career-opposite to his friend and contemporary from the early, hungry days in New York – James Dean. Maybe he would have ended his days regarded as hardly more than a safe pair of acting hands, were it not for three directors who saw in him that extraordinary inner power and maturity: Francis Ford Coppola, Tim Burton and Woody Allen.

Landau made his first real impression in his early 30s as James Mason’s unsmiling heavy in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. His good looks were uningratiating: saturnine and severe. But it was in television that he was first to make his mark. He was Rollin Hand in TV’s Mission: Impossible, a charismatic and slightly enigmatic member of the team. And later he became a much-loved presence in Lew Grade’s cult sci-fi TV drama of the 1970s, with its now quaint millennial title – Space: 1999. Landau was Commander John Koenig, and just as in Mission: Impossible, he starred with his wife, Barbara Bain. As ever, the key to his performance was the absolute seriousness he brought to it – particularly in that piercing, commanding gaze.

Coppola inaugurated the Martin Landau golden age in the late 80s by casting him in a widely admired film that underperformed at the box office: Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988), the story of Preston Tucker, the automobile design visionary, played by Jeff Bridges, who was squeezed out by corporate sharp practice. Landau plays Abe Karatz, the financial backer who fears his own shady past will destroy both Tucker and Karatz himself. It’s a small role that earned Landau his first Oscar nomination for best supporting actor. Landau is agonised, self-questioning and vulnerable, at once a kind of damaged father figure to Tucker and yet also perhaps someone who lets him down, like an errant son.

Landau actually landed his Oscar for his glorious performance on the third nomination as the washed-up horror icon Béla Lugosi in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994), playing opposite the unearthly young beauty of Johnny Depp as the notorious B-movie director Wood, the fanboy who was the only person willing to employ the eccentric, cantankerous old star. Landau was utterly superb, perhaps drawing on his own experience of knuckling down to the silliness that was Space: 1999 – affectionately as that show is still remembered, along with Landau in it.

Martin Landau utterly nailed the Lugosi voice, the uncompromising central European growl, although his rendering was far fruitier and raspier than the real thing. His lightly made up and prosthetised face really did resemble a vampire’s in daylight, and his sudden explosions of rage and amour-propre were an absolute joy. Comedy had never been Landau’s strong suit, but this was a masterly comic performance. And that piercing gaze was deployed to wonderful effect in Ed Wood, like a steampunk laser gun.

But it was his second Oscar nomination, for his deadly serious performance in Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors in 1989, that was his moment of real greatness. Landau plays a successful ophthalmologist, Judah Rosenthal, who has been having a longstanding affair with a blowsy flight attendant, Dolores Paley, played by Anjelica Huston – an affair that is going sour. Dolores threatens to destroy his marriage and his career and Judah contemplates a desperate, murderous act. For me, Judah’s criminal plunge, and Martin Landau’s performance, are the more unforgettable because they do not appear in a conventional thriller or noir, but because they are in a Woody Allen movie, in a story overtly juxtaposed with the more absurdly comic tale that occupies the film’s other half – a film-maker forced to earn a living by celebrating someone he loathes.

Landau’s cold-sweat despair at what he has done, his gaze into the abyss, his Dostoyevskian agony: it is all compelling. I will never forget my own real horror in seeing this film when it first came out – having naturally expected nothing more than laughs, and despite having sat through hundreds of fictional murders in genre pictures. Landau’s performance made it chillingly real.

Landau was a great actor who boosted the IQ and the substance of every movie he appeared in. Watching Ed Wood and Crimes and Misdemeanors again is a great way to remember him.

Monday 17 July 2017

Martin Landau was the handsome, intelligent, reflective actor who was respected for first-class work in the theatre, and for his consistency and professionalism in films and TV in the 60s and 70s. But he gloriously came into his own in movies in his later years. Landau grew into his gravitas, and also into bittersweet human comedy and tragedy, in ways that were unavailable to him as a younger man. Landau was destined to be the career-opposite to his friend and contemporary from the early, hungry days in New York – James Dean. Maybe he would have ended his days regarded as hardly more than a safe pair of acting hands, were it not for three directors who saw in him that extraordinary inner power and maturity: Francis Ford Coppola, Tim Burton and Woody Allen.

Landau made his first real impression in his early 30s as James Mason’s unsmiling heavy in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. His good looks were uningratiating: saturnine and severe. But it was in television that he was first to make his mark. He was Rollin Hand in TV’s Mission: Impossible, a charismatic and slightly enigmatic member of the team. And later he became a much-loved presence in Lew Grade’s cult sci-fi TV drama of the 1970s, with its now quaint millennial title – Space: 1999. Landau was Commander John Koenig, and just as in Mission: Impossible, he starred with his wife, Barbara Bain. As ever, the key to his performance was the absolute seriousness he brought to it – particularly in that piercing, commanding gaze.

Coppola inaugurated the Martin Landau golden age in the late 80s by casting him in a widely admired film that underperformed at the box office: Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988), the story of Preston Tucker, the automobile design visionary, played by Jeff Bridges, who was squeezed out by corporate sharp practice. Landau plays Abe Karatz, the financial backer who fears his own shady past will destroy both Tucker and Karatz himself. It’s a small role that earned Landau his first Oscar nomination for best supporting actor. Landau is agonised, self-questioning and vulnerable, at once a kind of damaged father figure to Tucker and yet also perhaps someone who lets him down, like an errant son.

Landau actually landed his Oscar for his glorious performance on the third nomination as the washed-up horror icon Béla Lugosi in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994), playing opposite the unearthly young beauty of Johnny Depp as the notorious B-movie director Wood, the fanboy who was the only person willing to employ the eccentric, cantankerous old star. Landau was utterly superb, perhaps drawing on his own experience of knuckling down to the silliness that was Space: 1999 – affectionately as that show is still remembered, along with Landau in it.

Martin Landau utterly nailed the Lugosi voice, the uncompromising central European growl, although his rendering was far fruitier and raspier than the real thing. His lightly made up and prosthetised face really did resemble a vampire’s in daylight, and his sudden explosions of rage and amour-propre were an absolute joy. Comedy had never been Landau’s strong suit, but this was a masterly comic performance. And that piercing gaze was deployed to wonderful effect in Ed Wood, like a steampunk laser gun.

But it was his second Oscar nomination, for his deadly serious performance in Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors in 1989, that was his moment of real greatness. Landau plays a successful ophthalmologist, Judah Rosenthal, who has been having a longstanding affair with a blowsy flight attendant, Dolores Paley, played by Anjelica Huston – an affair that is going sour. Dolores threatens to destroy his marriage and his career and Judah contemplates a desperate, murderous act. For me, Judah’s criminal plunge, and Martin Landau’s performance, are the more unforgettable because they do not appear in a conventional thriller or noir, but because they are in a Woody Allen movie, in a story overtly juxtaposed with the more absurdly comic tale that occupies the film’s other half – a film-maker forced to earn a living by celebrating someone he loathes.

Landau’s cold-sweat despair at what he has done, his gaze into the abyss, his Dostoyevskian agony: it is all compelling. I will never forget my own real horror in seeing this film when it first came out – having naturally expected nothing more than laughs, and despite having sat through hundreds of fictional murders in genre pictures. Landau’s performance made it chillingly real.

Landau was a great actor who boosted the IQ and the substance of every movie he appeared in. Watching Ed Wood and Crimes and Misdemeanors again is a great way to remember him.

Monday 17 July 2017

Sunday 16 July 2017

Saturday 15 July 2017

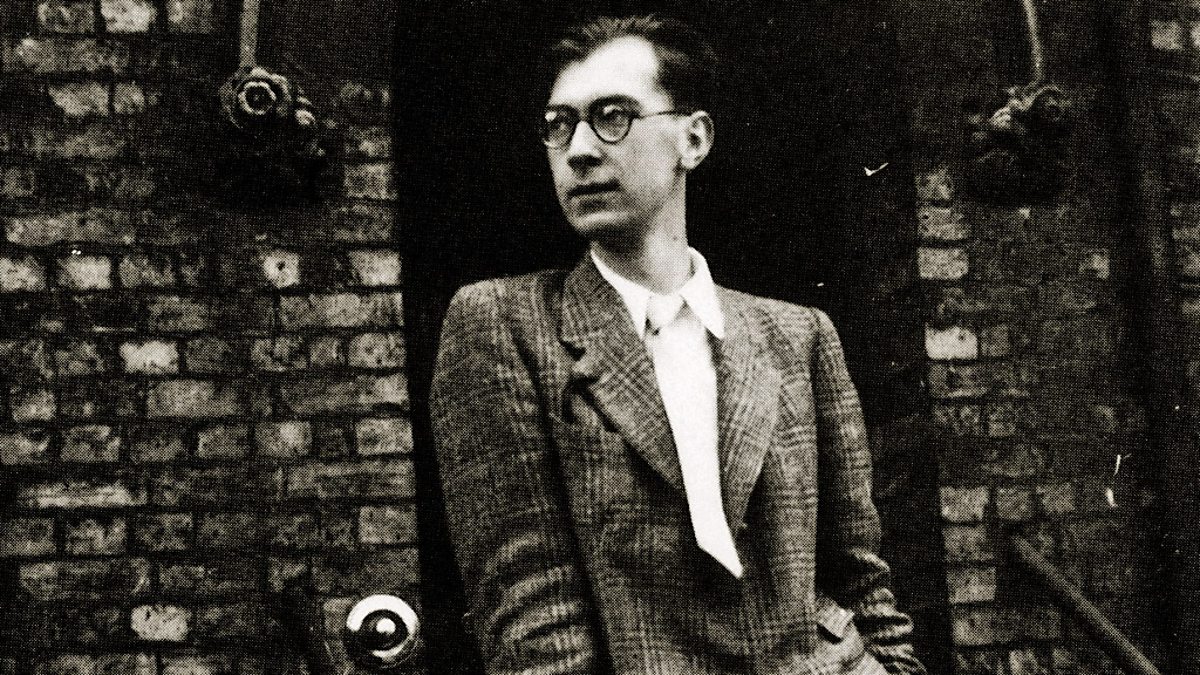

Philip Larkin: New Eyes Each Year - exhibition at the University of Hull

Hundreds of personal items gathered for city of culture show that does not shy away from darker sides of his personality

Hannah Ellis-Petersen

The Guardian

Tuesday 4 July 2017

Philip Larkin is many things to many people; to some a bleakly beautiful poet with a razor-sharp wit, to others a womanising misogynist whose casual racism is unforgivable.

It is into this morally complex minefield that a new exhibition, held in Hull’s Brynmor Jones library where he was famously the librarian, has waded, offering a new perspective on Larkin, one of the city’s most treasured cultural figures.

The exhibition, opened as part of Hull city of culture 2017, has gathered together hundreds of personal items from Larkin’s life, from his book collection to his clothes, ornaments from his office and home, unseen photographs, notes and doodles and objects belonging to his many lovers, to piece together a new and fascinating picture of the poet’s life.

Most of the objects were originally in Larkin’s home and have never been seen in public before. It is an exhibition that does not shy away from the complex, darker sides of Larkin’s personality. On display is the small figurine of Hitler, given to the poet by his Nazi-sympathiser father who once took Larkin to a Nuremberg Rally.

Also on display are the empty spines of the diaries that Larkin ordered to be shredded after he died, which are commonly thought to have contained mostly pornography.

The women in his life, particularly Monica Jones, Maeve Brennan and Betty Mackereth, feature prominently in the show as well, directly addressing the often despicable way that Larkin treated them – how he struggled with intimacy his whole life – but also how biographers and historians have often dismissed them simply as “mystic muses”, rather than acknowledging the active roles they often played as his editors.

“The challenge is always to not judge, and present the story in a way with lots of perspectives and hooks so people can make their own minds up,” said exhibition curator Anna Farthing. “I’ve had lots of different reactions to him as I’ve started to get to know him, from complete respect to being appalled.”

Larkin’s own library of books from his home is on display, and Farthing emphasised how fascinating it had been to look through the books, all of which were filled with scribbles and newspaper cuttings, pressed flowers and dedications, and she described each as a “casket in its own right”.

They also prove revealing. A copy of his novel Jill, given to Jones who was his longtime lover, is inscribed at the front: “To Monica, with love and thanks for helping make it decent, ie literate.”

Farthing pointed out the significance of these words. “There is so much about the women in Larkin’s life being his muse – well, they were human beings in their own right,” she said. “Yet here you can see she wasn’t his muse, she was his editor. All the evidence suggests he sends her drafts of his work, he’s constantly asking for her opinion. In her copy of The Whitsun Weddings, he writes a dedication in the front of it for her and inside the book there’s a draft of a poem, which has Tippex all over it. So what we are seeing here is working documents that they shared.”

Jones’s lipstick, her dress and objects of hers that were in Larkin’s house are also on display as part of the show, as well as what Farthing described as one of the most “heartbreaking” finds: unused dress patterns for small children, suggesting that she may have held out hope that she would be able to get Larkin to commit to her fully and start a family.

The show also offers a rare insight into Larkin’s own tortured relationship with his appearance. He was fixated on it, and the show displays both his clothes – beige trousers, bright red shirts and thick black glasses – as well as the many pictures he took of himself. Larkin would weigh himself twice a day on two different sets of weighing scales, and the exhibition displays quotes revealing the depth of his self-loathing.

Farthing said it was one of the biggest revelations in her research. “People presume that men don’t care about their body image and it’s a side of Larkin’s character that has been neglected,” she said.

“And maybe it’s because I’m a woman that I can see it instantly in his own neuroses. You just have to read his words: ‘my trousers seem to have been made for a much bigger creature, probably an elephant’ or ‘I staggered away from the table dreading my next encounter with the scales’. Those are not the words we expect to hear from Larkin, yet he was a man who had a real struggle with his own image.”

Larkin’s love of jazz is widely known and the show has a backing soundtrack of jazz, both in a nod to this passion but also to give a slinky rhythm to the show.

“The thing about libraries is that all sorts of things happen in the stacks,” said Farthing. “So we want people to go into the small corners and the nooks and crannies of this exhibition and have an experience with another human – that sounds suggestive but what I mean is, have a little chat, ask questions. Larkin found all his lovers in libraries.”

For Farthing, the exhibition is about exploring a side of Larkin that goes against expectation. The theme throughout is pink, which was Larkin’s favourite colour, and it focuses in on the scribblings, the unpublished thoughts and scratched out writings that are never seen in his sparse, clean poems. At the end of the show, people are also invited to pen their own letter to Larkin, which will then be pinned on to the wall.

“I think what I have taken away most from putting on this exhibition is that it seems extraordinary that he produced the work because the poetry is so clean and clear and his life was such a mess,” said Farthing. “He’s clearly a narcissist with a borderline personality disorder, but to have achieved work that is so human and engaging and continually relevant, it seems that he did it despite his demons, not because of them.”

Tuesday 4 July 2017

Philip Larkin is many things to many people; to some a bleakly beautiful poet with a razor-sharp wit, to others a womanising misogynist whose casual racism is unforgivable.

It is into this morally complex minefield that a new exhibition, held in Hull’s Brynmor Jones library where he was famously the librarian, has waded, offering a new perspective on Larkin, one of the city’s most treasured cultural figures.

The exhibition, opened as part of Hull city of culture 2017, has gathered together hundreds of personal items from Larkin’s life, from his book collection to his clothes, ornaments from his office and home, unseen photographs, notes and doodles and objects belonging to his many lovers, to piece together a new and fascinating picture of the poet’s life.

Most of the objects were originally in Larkin’s home and have never been seen in public before. It is an exhibition that does not shy away from the complex, darker sides of Larkin’s personality. On display is the small figurine of Hitler, given to the poet by his Nazi-sympathiser father who once took Larkin to a Nuremberg Rally.

Also on display are the empty spines of the diaries that Larkin ordered to be shredded after he died, which are commonly thought to have contained mostly pornography.

The women in his life, particularly Monica Jones, Maeve Brennan and Betty Mackereth, feature prominently in the show as well, directly addressing the often despicable way that Larkin treated them – how he struggled with intimacy his whole life – but also how biographers and historians have often dismissed them simply as “mystic muses”, rather than acknowledging the active roles they often played as his editors.

“The challenge is always to not judge, and present the story in a way with lots of perspectives and hooks so people can make their own minds up,” said exhibition curator Anna Farthing. “I’ve had lots of different reactions to him as I’ve started to get to know him, from complete respect to being appalled.”

Larkin’s own library of books from his home is on display, and Farthing emphasised how fascinating it had been to look through the books, all of which were filled with scribbles and newspaper cuttings, pressed flowers and dedications, and she described each as a “casket in its own right”.

They also prove revealing. A copy of his novel Jill, given to Jones who was his longtime lover, is inscribed at the front: “To Monica, with love and thanks for helping make it decent, ie literate.”

Farthing pointed out the significance of these words. “There is so much about the women in Larkin’s life being his muse – well, they were human beings in their own right,” she said. “Yet here you can see she wasn’t his muse, she was his editor. All the evidence suggests he sends her drafts of his work, he’s constantly asking for her opinion. In her copy of The Whitsun Weddings, he writes a dedication in the front of it for her and inside the book there’s a draft of a poem, which has Tippex all over it. So what we are seeing here is working documents that they shared.”

Jones’s lipstick, her dress and objects of hers that were in Larkin’s house are also on display as part of the show, as well as what Farthing described as one of the most “heartbreaking” finds: unused dress patterns for small children, suggesting that she may have held out hope that she would be able to get Larkin to commit to her fully and start a family.

The show also offers a rare insight into Larkin’s own tortured relationship with his appearance. He was fixated on it, and the show displays both his clothes – beige trousers, bright red shirts and thick black glasses – as well as the many pictures he took of himself. Larkin would weigh himself twice a day on two different sets of weighing scales, and the exhibition displays quotes revealing the depth of his self-loathing.

Farthing said it was one of the biggest revelations in her research. “People presume that men don’t care about their body image and it’s a side of Larkin’s character that has been neglected,” she said.

“And maybe it’s because I’m a woman that I can see it instantly in his own neuroses. You just have to read his words: ‘my trousers seem to have been made for a much bigger creature, probably an elephant’ or ‘I staggered away from the table dreading my next encounter with the scales’. Those are not the words we expect to hear from Larkin, yet he was a man who had a real struggle with his own image.”

Larkin’s love of jazz is widely known and the show has a backing soundtrack of jazz, both in a nod to this passion but also to give a slinky rhythm to the show.

“The thing about libraries is that all sorts of things happen in the stacks,” said Farthing. “So we want people to go into the small corners and the nooks and crannies of this exhibition and have an experience with another human – that sounds suggestive but what I mean is, have a little chat, ask questions. Larkin found all his lovers in libraries.”

For Farthing, the exhibition is about exploring a side of Larkin that goes against expectation. The theme throughout is pink, which was Larkin’s favourite colour, and it focuses in on the scribblings, the unpublished thoughts and scratched out writings that are never seen in his sparse, clean poems. At the end of the show, people are also invited to pen their own letter to Larkin, which will then be pinned on to the wall.

“I think what I have taken away most from putting on this exhibition is that it seems extraordinary that he produced the work because the poetry is so clean and clear and his life was such a mess,” said Farthing. “He’s clearly a narcissist with a borderline personality disorder, but to have achieved work that is so human and engaging and continually relevant, it seems that he did it despite his demons, not because of them.”

Friday 14 July 2017

Dead Poets Society #45 Miroslav Holub: Casualty

They bring us crushed fingers,

mend it, doctor.

They bring burnt-out eyes,

hounded owls of hearts,

they bring a hundred white bodies,

a hundred red bodies,

a hundred black bodies,

mend it, doctor,

on the dishes of ambulances they bring

the madness of blood,

the scream of flesh,

the silence of charring,

mend it, doctor.

And while we are suturing

inch after inch,

night after night,

nerve to nerve,

muscle to muscle,

eyes to sight,

they bring in

even longer daggers,

even more dangerous bombs,

even more glorious victories,

idiots.

Thursday 13 July 2017

Peter Bogdanovich - Saturday Morning Pictures (BBC)

Peter Bogdanovich's Saturday Morning Pictures

Episode 1

The golden age of Hollywood, before the 1960s dawned.

American actor, author and film director Peter Bogdanovich shares his views of the movie industry in Hollywood, using his own archive of recordings. Featuring James Stewart, John Ford, Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock in conversation and Cybill Shepherd reveals what it was like to have Orson Welles as a house guest.

Episode 2

The Last Picture Show placed Peter Bogdanovich in the vanguard of what was dubbed New Hollywood.

The director and historian looks at the changes in Hollywood since his arrival there in 1961 - from the rise of independent film makers to the influence of television.

First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2007.

The golden age of Hollywood, before the 1960s dawned.

American actor, author and film director Peter Bogdanovich shares his views of the movie industry in Hollywood, using his own archive of recordings. Featuring James Stewart, John Ford, Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock in conversation and Cybill Shepherd reveals what it was like to have Orson Welles as a house guest.

You have 27 days left to listen: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b007zzjx

The Last Picture Show placed Peter Bogdanovich in the vanguard of what was dubbed New Hollywood.

The director and historian looks at the changes in Hollywood since his arrival there in 1961 - from the rise of independent film makers to the influence of television.

First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2007.

Producer Penny Vine

You have 28 days left to listen: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0080lss

Tuesday 11 July 2017

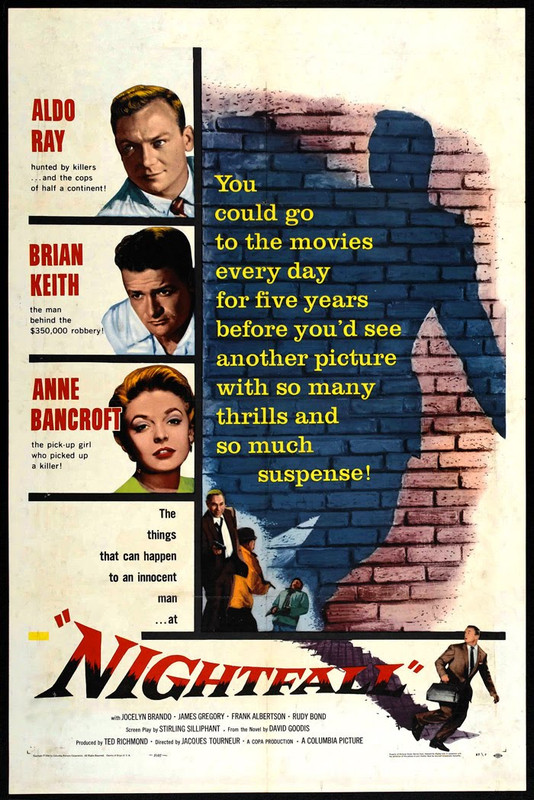

Noir of the Week #6* - Nightfall (Jacques Tourneur, 1957)

Frank Black

11 July 2017

Thanks to his work with Val Lewton in the 1950s and that late gem, Night of the Demon (1957), Jacques Tourneur will be forever associated with the horror genre, but a considered look at his career will see that this supreme stylist made films in many genres, including one of the greatest film noirs, Out of the Past (1947).

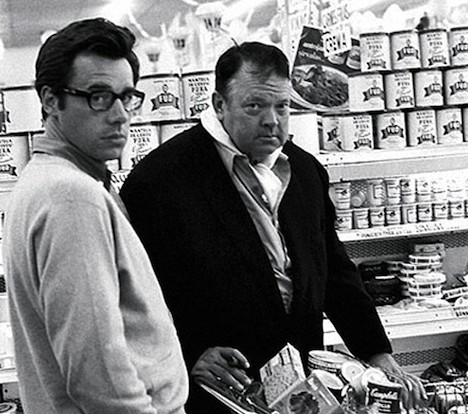

Nightfall is a smart little crime drama, tightly-scripted by Stirling Silliphant and based on a novel by David Goodis, who wrote several nourish thrillers that were adapted into movies, including Down There, filmed by Francois Truffaut as Shoot the Piano Player (1960), Delmer Daves’ Dark Passage (1946) and The Burglar, directed by Paul Wendkos (1957).

Like Out of the Past, an event from the protagonist’s history comes to determine his life in the present and flashbacks play a key role; however, unlike Out of the Past’s one flashback section, the narrative in Nightfall is punctuated by a series of flashbacks that explain the origin of the events until past meets present in snowy Wyoming and the story is violently resolved.

Tourneur presents the audience with an enigma from the outset. A young man, Art Rayburn (Aldo Rey), who has taken the name Jim Vanning, wanders through a newsstand, checking out newspapers from across the United States. He asks for one from Evanston, Illinois, but it’s the only one they don’t have, symbolising that this is a man out of place. To underline this, when the lights flicker on, Vanning, shot from behind, reacts with a nervous jump, as if someone is after him. Who is this man and why does he act this way?

Leaving the brightness of the shop, he is filmed in long shot from across the street, bathed in classic Tourneur chiaroscuro, implying guilt or trouble - or perhaps someone about to emerge from the darkness of his past. He looks over his shoulder as if he fears he’s being followed – and it seems he is. Crossing into the shot is Ben Fraser (James Gregory), who we later discover is an insurance investigator, and he walks up to Vanning and makes small talk before catching a bus home.

The nature of the suspected crime isn’t revealed at first, but throughout the film, Fraser seems to doubt Vanning’s guilt, expressing this his wife, Laura (Jocelyn Brando), and on several occasions Tourneur uses editing to hint at a bond between them; for example, after Laura goes to make Fraser a drink, there’s a cut to coffee being poured at Vanning’s table.

Thanks to his work with Val Lewton in the 1950s and that late gem, Night of the Demon (1957), Jacques Tourneur will be forever associated with the horror genre, but a considered look at his career will see that this supreme stylist made films in many genres, including one of the greatest film noirs, Out of the Past (1947).

Nightfall is a smart little crime drama, tightly-scripted by Stirling Silliphant and based on a novel by David Goodis, who wrote several nourish thrillers that were adapted into movies, including Down There, filmed by Francois Truffaut as Shoot the Piano Player (1960), Delmer Daves’ Dark Passage (1946) and The Burglar, directed by Paul Wendkos (1957).

Like Out of the Past, an event from the protagonist’s history comes to determine his life in the present and flashbacks play a key role; however, unlike Out of the Past’s one flashback section, the narrative in Nightfall is punctuated by a series of flashbacks that explain the origin of the events until past meets present in snowy Wyoming and the story is violently resolved.

Tourneur presents the audience with an enigma from the outset. A young man, Art Rayburn (Aldo Rey), who has taken the name Jim Vanning, wanders through a newsstand, checking out newspapers from across the United States. He asks for one from Evanston, Illinois, but it’s the only one they don’t have, symbolising that this is a man out of place. To underline this, when the lights flicker on, Vanning, shot from behind, reacts with a nervous jump, as if someone is after him. Who is this man and why does he act this way?

Leaving the brightness of the shop, he is filmed in long shot from across the street, bathed in classic Tourneur chiaroscuro, implying guilt or trouble - or perhaps someone about to emerge from the darkness of his past. He looks over his shoulder as if he fears he’s being followed – and it seems he is. Crossing into the shot is Ben Fraser (James Gregory), who we later discover is an insurance investigator, and he walks up to Vanning and makes small talk before catching a bus home.

The nature of the suspected crime isn’t revealed at first, but throughout the film, Fraser seems to doubt Vanning’s guilt, expressing this his wife, Laura (Jocelyn Brando), and on several occasions Tourneur uses editing to hint at a bond between them; for example, after Laura goes to make Fraser a drink, there’s a cut to coffee being poured at Vanning’s table.

The narrative emphasises the role of chance and coincidence, which play on Vanning’s paranoia. In a bar, he meets a young model, Marie (Anne Bancroft) and it seems like she’s hitting on him and wants the loan of some money to pay her bill; of course, in keeping with generic norms, they hit it off. Leaving the bar, he’s jumped by the two killers who’ve been tracking him and they order her to go away. It seems like the classic noir femme fatale set-up, but it becomes apparent that it wasn’t intentional: there was no set-up and she really did need the money to pay her for her drink. He pointedly tells her, “… you were unlucky enough to talk to me tonight.”

The foregrounding of coincidence continues throughout the film; indeed Vanning’s initial involvement with the killers is purely down to unconscious chance as revealed in one of the flashbacks set in the snow-covered wilds of Wyoming where a hunting trip with his friend, Doc Gurston (Frank Albertson), is interrupted by an accident when a car swerves off an icy road.

Gurston and Vanning rush to help, but the crash victims turn out to be bank robbers, the subdued, almost eerily pleasant John (Brian Keith) and the borderline psychotic Red (Rudy Bond), prefiguring the kind of relationship between killers that feature in Quentin Tarantino's work. Gurston fixes John’s arm and then is shot by Red, who also shoots Vanning and leaves him for dead. He’s alive, of course, and on waking, he finds the robbers have taken Gurston’s bag instead of the one filled with cash. Vanning escapes, by now with John and Red in pursuit, and he leaves the bag hidden before running off and creating a new life for himself, all the time in the knowledge that he has gone from being the hunter to the prey.

Tourneur’s cinematographer was Burnett Guffey, an Oscar-winner for his work on Fred Zinneman’s From Here to Eterntity (1953) and, later, for Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), but also well-versed in noir over a series of films that included Nicholas Ray’s masterpiece, In a Lonely Place (1950). He makes stunning use of the stark, dazzling white landscape of the Wyoming hills juxtaposed with the moody blacks and greys of the scenes in the present, particularly during the sequence when the killers take Vanning to an oilfield at dusk to extract information.

The claustrophobic and threatening environment of the constantly moving predatory derricks contrasts with the flashbacks of the clean, natural white open spaces of Wyoming, while the editing helps create tension for the audience, prolonging Vanning’s captivity. As the flashbacks reveal more, the stark whiteness becomes sullied with the presence of John and Red. Of course, Wyoming looks clean because of the snow, but it’s the snow that later hides the reason behind the killers’ pursuit of Vanning: the dirty money stolen in the bank-job.

It’s also in Wyoming that things finally come to a head. Escaping the city with Marie, Vanning takes a bus to locate the money, unaware that the diligent Fraser is only a few seats behind them. Finally, he approaches Vanning while he waits outside a church for Marie. The mise-en-scène positions Vanning as an outsider and with his back towards the camera, the shot echoing the earlier one where he flinches when the lights come on at the newsagents just before Fraser enters his life; the presence of the church, however, hints at confession and redemption. The scene is carried by Rey and Gregory’s easy-going, naturalistic style as Vanning opens up to Fraser and confirms the latter’s suspicion that he has been innocent all along.

After Red shot Doc Gurston, he forced Vanning to pick up the gun that killed him. By chance, Red fails to kill Vanning but his fingerprints were now on the rifle and – another coincidence - unbeknownst to the killers, Gurston’s wife had sent Vanning unrequited love letters, so he became a suspect for the murder as well as the robbery.

Coincidence rears its head again when Vanning, Fraser and Marie go to locate the money in the melting Wyoming snow. They approach a shack seemingly in the middle of nowhere and as Vanning walks around it, the angle of the camera reveals John and Red, the contrast in their manner engendering further anxiety, but they squabble and John’s low key approach is his downfall as Red shoots him dead in the same cold-hearted manner as he killed Gurston. Vanning launches himself towards John’s gun and a fight ensues on board a snow plough. While the will it/won’t it suspense of whether or not it will demolish the shack where Fraser and Marie are tied up conjures up the Perils of Pauline, real tension is created by Tourneur’s use of close-ups of Red and Vanning as they tussle in the plough’s cabin and when the former is pushed out, the use of the point of view shot as the blades come whirling closer to Red underlines his own stark brutality – and perhaps gave the Coen Brothers something to allude to when they made Fargo almost forty years later.

If you can ignore the awful theme tune crooned by Duke Ellington alumnus Al Hibbler, this is a rewarding late period noir, with an engaging, twisted plot, superbly handled by a master of mood and suspense and well-acted by a cast of fairly minor players.

* Okay, maybe more like once in a blue moon...

Gurston and Vanning rush to help, but the crash victims turn out to be bank robbers, the subdued, almost eerily pleasant John (Brian Keith) and the borderline psychotic Red (Rudy Bond), prefiguring the kind of relationship between killers that feature in Quentin Tarantino's work. Gurston fixes John’s arm and then is shot by Red, who also shoots Vanning and leaves him for dead. He’s alive, of course, and on waking, he finds the robbers have taken Gurston’s bag instead of the one filled with cash. Vanning escapes, by now with John and Red in pursuit, and he leaves the bag hidden before running off and creating a new life for himself, all the time in the knowledge that he has gone from being the hunter to the prey.

Tourneur’s cinematographer was Burnett Guffey, an Oscar-winner for his work on Fred Zinneman’s From Here to Eterntity (1953) and, later, for Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), but also well-versed in noir over a series of films that included Nicholas Ray’s masterpiece, In a Lonely Place (1950). He makes stunning use of the stark, dazzling white landscape of the Wyoming hills juxtaposed with the moody blacks and greys of the scenes in the present, particularly during the sequence when the killers take Vanning to an oilfield at dusk to extract information.

The claustrophobic and threatening environment of the constantly moving predatory derricks contrasts with the flashbacks of the clean, natural white open spaces of Wyoming, while the editing helps create tension for the audience, prolonging Vanning’s captivity. As the flashbacks reveal more, the stark whiteness becomes sullied with the presence of John and Red. Of course, Wyoming looks clean because of the snow, but it’s the snow that later hides the reason behind the killers’ pursuit of Vanning: the dirty money stolen in the bank-job.

It’s also in Wyoming that things finally come to a head. Escaping the city with Marie, Vanning takes a bus to locate the money, unaware that the diligent Fraser is only a few seats behind them. Finally, he approaches Vanning while he waits outside a church for Marie. The mise-en-scène positions Vanning as an outsider and with his back towards the camera, the shot echoing the earlier one where he flinches when the lights come on at the newsagents just before Fraser enters his life; the presence of the church, however, hints at confession and redemption. The scene is carried by Rey and Gregory’s easy-going, naturalistic style as Vanning opens up to Fraser and confirms the latter’s suspicion that he has been innocent all along.

After Red shot Doc Gurston, he forced Vanning to pick up the gun that killed him. By chance, Red fails to kill Vanning but his fingerprints were now on the rifle and – another coincidence - unbeknownst to the killers, Gurston’s wife had sent Vanning unrequited love letters, so he became a suspect for the murder as well as the robbery.

Coincidence rears its head again when Vanning, Fraser and Marie go to locate the money in the melting Wyoming snow. They approach a shack seemingly in the middle of nowhere and as Vanning walks around it, the angle of the camera reveals John and Red, the contrast in their manner engendering further anxiety, but they squabble and John’s low key approach is his downfall as Red shoots him dead in the same cold-hearted manner as he killed Gurston. Vanning launches himself towards John’s gun and a fight ensues on board a snow plough. While the will it/won’t it suspense of whether or not it will demolish the shack where Fraser and Marie are tied up conjures up the Perils of Pauline, real tension is created by Tourneur’s use of close-ups of Red and Vanning as they tussle in the plough’s cabin and when the former is pushed out, the use of the point of view shot as the blades come whirling closer to Red underlines his own stark brutality – and perhaps gave the Coen Brothers something to allude to when they made Fargo almost forty years later.

If you can ignore the awful theme tune crooned by Duke Ellington alumnus Al Hibbler, this is a rewarding late period noir, with an engaging, twisted plot, superbly handled by a master of mood and suspense and well-acted by a cast of fairly minor players.

* Okay, maybe more like once in a blue moon...

Monday 10 July 2017

Sunday 9 July 2017

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)