Hundreds of personal items gathered for city of culture show that does not shy away from darker sides of his personality

Hannah Ellis-Petersen

The Guardian

Tuesday 4 July 2017

Philip Larkin is many things to many people; to some a bleakly beautiful poet with a razor-sharp wit, to others a womanising misogynist whose casual racism is unforgivable.

It is into this morally complex minefield that a new exhibition, held in Hull’s Brynmor Jones library where he was famously the librarian, has waded, offering a new perspective on Larkin, one of the city’s most treasured cultural figures.

The exhibition, opened as part of Hull city of culture 2017, has gathered together hundreds of personal items from Larkin’s life, from his book collection to his clothes, ornaments from his office and home, unseen photographs, notes and doodles and objects belonging to his many lovers, to piece together a new and fascinating picture of the poet’s life.

Most of the objects were originally in Larkin’s home and have never been seen in public before. It is an exhibition that does not shy away from the complex, darker sides of Larkin’s personality. On display is the small figurine of Hitler, given to the poet by his Nazi-sympathiser father who once took Larkin to a Nuremberg Rally.

Also on display are the empty spines of the diaries that Larkin ordered to be shredded after he died, which are commonly thought to have contained mostly pornography.

The women in his life, particularly Monica Jones, Maeve Brennan and Betty Mackereth, feature prominently in the show as well, directly addressing the often despicable way that Larkin treated them – how he struggled with intimacy his whole life – but also how biographers and historians have often dismissed them simply as “mystic muses”, rather than acknowledging the active roles they often played as his editors.

“The challenge is always to not judge, and present the story in a way with lots of perspectives and hooks so people can make their own minds up,” said exhibition curator Anna Farthing. “I’ve had lots of different reactions to him as I’ve started to get to know him, from complete respect to being appalled.”

Larkin’s own library of books from his home is on display, and Farthing emphasised how fascinating it had been to look through the books, all of which were filled with scribbles and newspaper cuttings, pressed flowers and dedications, and she described each as a “casket in its own right”.

They also prove revealing. A copy of his novel Jill, given to Jones who was his longtime lover, is inscribed at the front: “To Monica, with love and thanks for helping make it decent, ie literate.”

Farthing pointed out the significance of these words. “There is so much about the women in Larkin’s life being his muse – well, they were human beings in their own right,” she said. “Yet here you can see she wasn’t his muse, she was his editor. All the evidence suggests he sends her drafts of his work, he’s constantly asking for her opinion. In her copy of The Whitsun Weddings, he writes a dedication in the front of it for her and inside the book there’s a draft of a poem, which has Tippex all over it. So what we are seeing here is working documents that they shared.”

Jones’s lipstick, her dress and objects of hers that were in Larkin’s house are also on display as part of the show, as well as what Farthing described as one of the most “heartbreaking” finds: unused dress patterns for small children, suggesting that she may have held out hope that she would be able to get Larkin to commit to her fully and start a family.

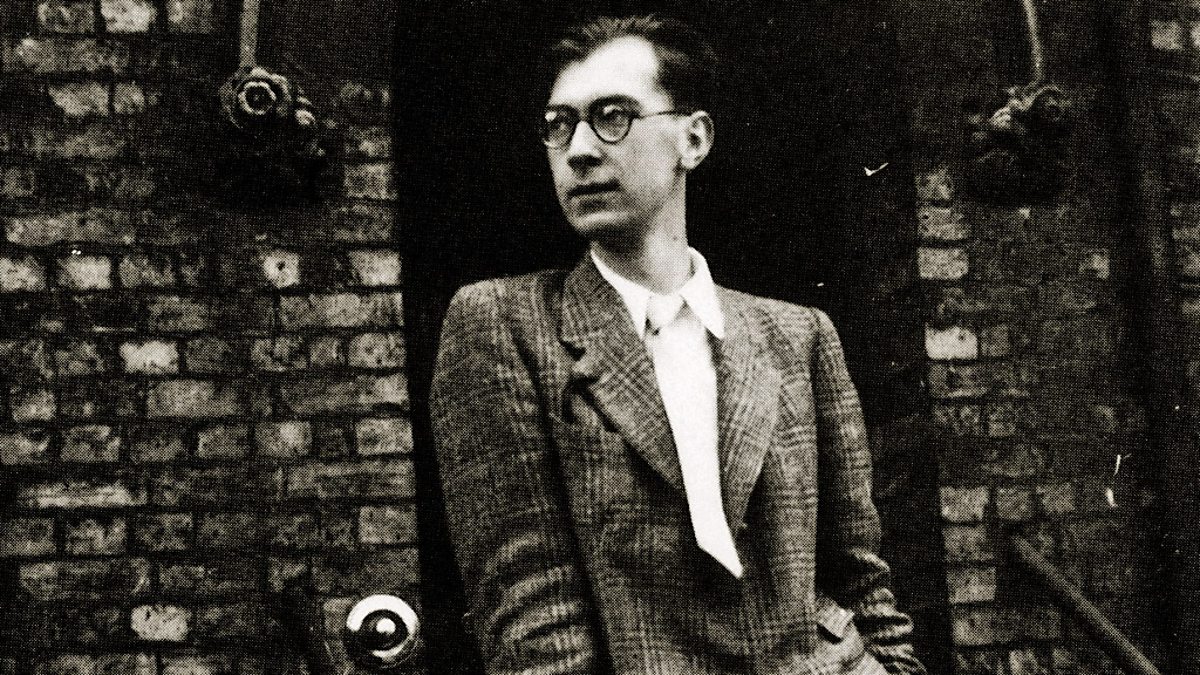

The show also offers a rare insight into Larkin’s own tortured relationship with his appearance. He was fixated on it, and the show displays both his clothes – beige trousers, bright red shirts and thick black glasses – as well as the many pictures he took of himself. Larkin would weigh himself twice a day on two different sets of weighing scales, and the exhibition displays quotes revealing the depth of his self-loathing.

Farthing said it was one of the biggest revelations in her research. “People presume that men don’t care about their body image and it’s a side of Larkin’s character that has been neglected,” she said.

“And maybe it’s because I’m a woman that I can see it instantly in his own neuroses. You just have to read his words: ‘my trousers seem to have been made for a much bigger creature, probably an elephant’ or ‘I staggered away from the table dreading my next encounter with the scales’. Those are not the words we expect to hear from Larkin, yet he was a man who had a real struggle with his own image.”

Larkin’s love of jazz is widely known and the show has a backing soundtrack of jazz, both in a nod to this passion but also to give a slinky rhythm to the show.

“The thing about libraries is that all sorts of things happen in the stacks,” said Farthing. “So we want people to go into the small corners and the nooks and crannies of this exhibition and have an experience with another human – that sounds suggestive but what I mean is, have a little chat, ask questions. Larkin found all his lovers in libraries.”

For Farthing, the exhibition is about exploring a side of Larkin that goes against expectation. The theme throughout is pink, which was Larkin’s favourite colour, and it focuses in on the scribblings, the unpublished thoughts and scratched out writings that are never seen in his sparse, clean poems. At the end of the show, people are also invited to pen their own letter to Larkin, which will then be pinned on to the wall.

“I think what I have taken away most from putting on this exhibition is that it seems extraordinary that he produced the work because the poetry is so clean and clear and his life was such a mess,” said Farthing. “He’s clearly a narcissist with a borderline personality disorder, but to have achieved work that is so human and engaging and continually relevant, it seems that he did it despite his demons, not because of them.”

Tuesday 4 July 2017

Philip Larkin is many things to many people; to some a bleakly beautiful poet with a razor-sharp wit, to others a womanising misogynist whose casual racism is unforgivable.

It is into this morally complex minefield that a new exhibition, held in Hull’s Brynmor Jones library where he was famously the librarian, has waded, offering a new perspective on Larkin, one of the city’s most treasured cultural figures.

The exhibition, opened as part of Hull city of culture 2017, has gathered together hundreds of personal items from Larkin’s life, from his book collection to his clothes, ornaments from his office and home, unseen photographs, notes and doodles and objects belonging to his many lovers, to piece together a new and fascinating picture of the poet’s life.

Most of the objects were originally in Larkin’s home and have never been seen in public before. It is an exhibition that does not shy away from the complex, darker sides of Larkin’s personality. On display is the small figurine of Hitler, given to the poet by his Nazi-sympathiser father who once took Larkin to a Nuremberg Rally.

Also on display are the empty spines of the diaries that Larkin ordered to be shredded after he died, which are commonly thought to have contained mostly pornography.

The women in his life, particularly Monica Jones, Maeve Brennan and Betty Mackereth, feature prominently in the show as well, directly addressing the often despicable way that Larkin treated them – how he struggled with intimacy his whole life – but also how biographers and historians have often dismissed them simply as “mystic muses”, rather than acknowledging the active roles they often played as his editors.

“The challenge is always to not judge, and present the story in a way with lots of perspectives and hooks so people can make their own minds up,” said exhibition curator Anna Farthing. “I’ve had lots of different reactions to him as I’ve started to get to know him, from complete respect to being appalled.”

Larkin’s own library of books from his home is on display, and Farthing emphasised how fascinating it had been to look through the books, all of which were filled with scribbles and newspaper cuttings, pressed flowers and dedications, and she described each as a “casket in its own right”.

They also prove revealing. A copy of his novel Jill, given to Jones who was his longtime lover, is inscribed at the front: “To Monica, with love and thanks for helping make it decent, ie literate.”

Farthing pointed out the significance of these words. “There is so much about the women in Larkin’s life being his muse – well, they were human beings in their own right,” she said. “Yet here you can see she wasn’t his muse, she was his editor. All the evidence suggests he sends her drafts of his work, he’s constantly asking for her opinion. In her copy of The Whitsun Weddings, he writes a dedication in the front of it for her and inside the book there’s a draft of a poem, which has Tippex all over it. So what we are seeing here is working documents that they shared.”

Jones’s lipstick, her dress and objects of hers that were in Larkin’s house are also on display as part of the show, as well as what Farthing described as one of the most “heartbreaking” finds: unused dress patterns for small children, suggesting that she may have held out hope that she would be able to get Larkin to commit to her fully and start a family.

The show also offers a rare insight into Larkin’s own tortured relationship with his appearance. He was fixated on it, and the show displays both his clothes – beige trousers, bright red shirts and thick black glasses – as well as the many pictures he took of himself. Larkin would weigh himself twice a day on two different sets of weighing scales, and the exhibition displays quotes revealing the depth of his self-loathing.

Farthing said it was one of the biggest revelations in her research. “People presume that men don’t care about their body image and it’s a side of Larkin’s character that has been neglected,” she said.

“And maybe it’s because I’m a woman that I can see it instantly in his own neuroses. You just have to read his words: ‘my trousers seem to have been made for a much bigger creature, probably an elephant’ or ‘I staggered away from the table dreading my next encounter with the scales’. Those are not the words we expect to hear from Larkin, yet he was a man who had a real struggle with his own image.”

Larkin’s love of jazz is widely known and the show has a backing soundtrack of jazz, both in a nod to this passion but also to give a slinky rhythm to the show.

“The thing about libraries is that all sorts of things happen in the stacks,” said Farthing. “So we want people to go into the small corners and the nooks and crannies of this exhibition and have an experience with another human – that sounds suggestive but what I mean is, have a little chat, ask questions. Larkin found all his lovers in libraries.”

For Farthing, the exhibition is about exploring a side of Larkin that goes against expectation. The theme throughout is pink, which was Larkin’s favourite colour, and it focuses in on the scribblings, the unpublished thoughts and scratched out writings that are never seen in his sparse, clean poems. At the end of the show, people are also invited to pen their own letter to Larkin, which will then be pinned on to the wall.

“I think what I have taken away most from putting on this exhibition is that it seems extraordinary that he produced the work because the poetry is so clean and clear and his life was such a mess,” said Farthing. “He’s clearly a narcissist with a borderline personality disorder, but to have achieved work that is so human and engaging and continually relevant, it seems that he did it despite his demons, not because of them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment