Friday 30 November 2018

Thursday 29 November 2018

Bernardo Bertolucci RIP

Film director acclaimed for Last Tango in Paris and the Oscar-winning The Last Emperor

Ronald Bergan

The Guardian

Mon 26 Nov 2018

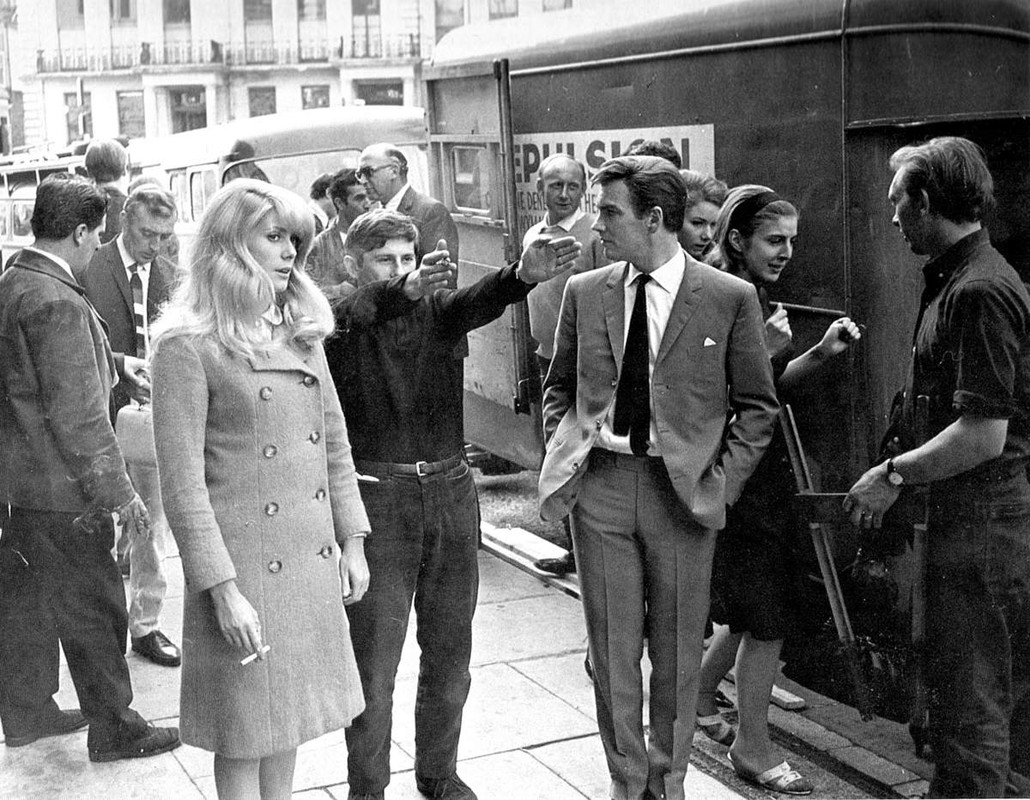

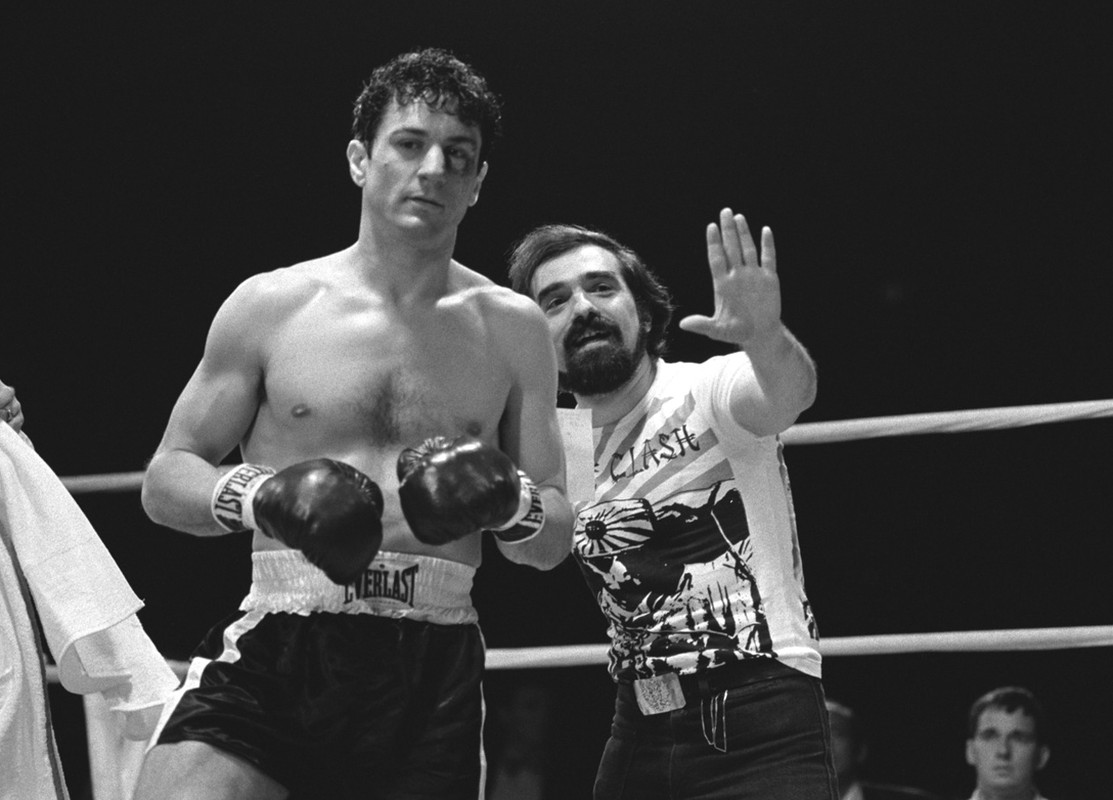

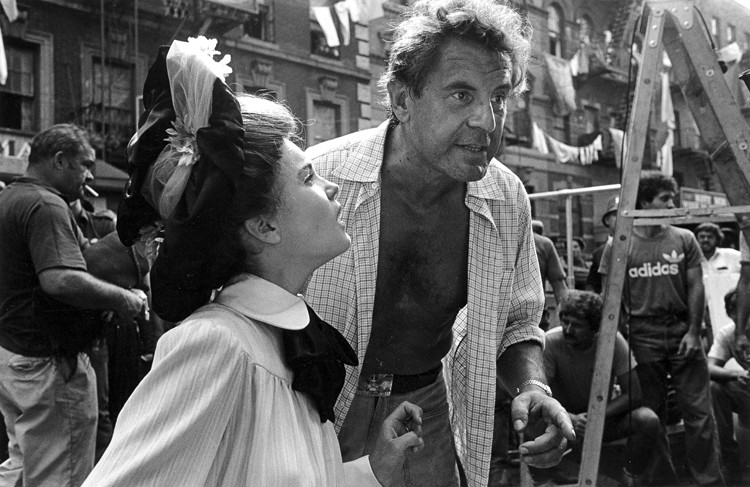

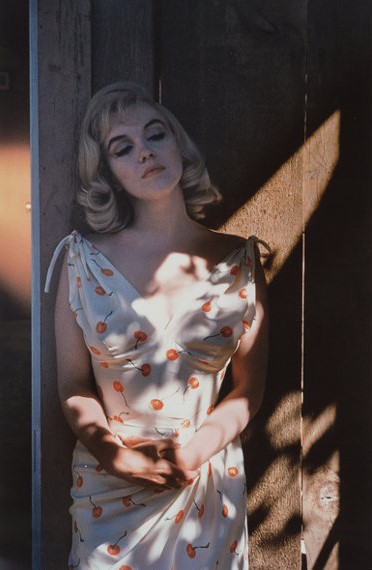

Having already made a reputation as one of the greatest Italian film directors of his generation, Bernardo Bertolucci, who has died aged 77, gained worldwide notoriety with Last Tango in Paris (1972), mainly as a result of its explicit sex scenes. In his depiction of the painful, loveless, joyless relationship between a middle-aged American man (Marlon Brando) and a young Frenchwoman (Maria Schneider), Bertolucci set out to show, he said, that “every sexual relationship is condemned”.

Fifteen years later, Bertolucci gained his greatest international triumph with The Last Emperor (1987), which won nine Oscars. According to Bertolucci, cinema is “a truly poetic language”, a claim that many of his films justify. He had started out as a poet, with his collection In Cerca del Mistero (In Search of Mystery) winning the Viareggio prize in 1962, as his father had done before him.

He was the son of Attilio Bertolucci, a well-known Italian poet, and Ninetta (nee Giovanardi), a school teacher. As a boy Bernardo often accompanied his father to the cinema in Parma, the city where he was born and brought up, and began making 16mm films when he was 16 years old. He got to know the poet Pier Paolo Pasolini through his father, and when Pasolini made his first film, Accatone (1961), Bernardo was hired as production assistant.

A year later he directed his first feature, The Grim Reaper (La Commare Secca), based on a five-page story outline by Pasolini. It told of an investigation into the murder of a prostitute in Rome, seen from different perspectives of different people on the events of her last day. Each episode, as told to the unseen investigator, was filmed in a different style. It is, as the director admitted, the film of “someone who had never shot one foot of 35mm before but who had seen lots and lots of films”.

Before the Revolution (1964), a far more personal film, explores the problems of a selfish middle-class young man who is torn between radical politics and conformity, and between a passionate affair with his young aunt and bourgeois marriage. He opts for respectability on both counts. The film, loosely based on Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, is technically impressive, as is Bertolucci’s ability to articulate themes, such as the betrayal of a totemic father and the connection of the libido with politics, that would mature in his later work. However, as with the film’s hero, there is an element of the dilettante in Bertolucci’s approach.

This impression grew stronger in Partner (1968), which is an undigested homage to Jean-Luc Godard, about a young man literally divided into two by having a double. Derived from Dostoevsky’s short novel The Double, and updated to the Rome of 1968, it has the central character, played by Pierre Clémenti, speaking French while all the rest speak Italian. In the same year, Bertolucci was credited with the story of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West.

Bertolucci’s reputation was greatly enhanced when he joined forces with the cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who had been a camera operator on Before the Revolution. The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), the first of eight films they made together as director and director of photography, easily transposed the Jorge Luis Borges story Theme of the Traitor and the Hero from Ireland to Italy. As oedipal and labyrinthine as its source, it concerns a young man who revisits the village in the Po valley where his father was murdered by the fascists in 1936, and gradually discovers that his father, whom he had considered a hero, was really a traitor.

The Conformist (1970) most successfully brings together Bertolucci’s Freudian and political preoccupations in an ironic study of pre-war Italy (beautifully captured by Storaro) and an attempt to penetrate the mind of ordinary fascism. The childhood trauma of having shot a chauffeur who tried to seduce him, together with his own repressed homosexuality, is a strong factor in making Marcello (Jean-Louis Trintignant) contract a bourgeois marriage and offer his services to the fascist party, for whom he is asked to assassinate his former professor. The Conformist saw the full flowering of Bertolucci’s flamboyant style – elaborate tracking shots, baroque camera angles, opulent colour effects, ornate décor and the intricate play of light and shadow that give his work such a distinctive surface.

After the release of Last Tango in Paris in Europe, Bertolucci was indicted by a court in Bologna for making a pornographic film. Although he was acquitted, he lost his civil rights (including his right to vote) for five years and the Italian courts ordered that all copies of the film should be destroyed. In recent years, further controversy surrounded the extent to which Schneider had consented to elements of the film shoot.

The worldwide acclaim and box office for Last Tango in Paris helped Bertolucci obtain the vast financial resources needed to embark on the long-planned project 1900. With this $6m, five-hour epic, released in 1977, Bertolucci turned away from the introspection of his previous films and tried to make a popular movie of the class struggle using the style of both American epics and the socialist realism of the Russian cinema of the 30s. Italian history is seen through the diverging lives of Olmo (Gérard Depardieu), the son of a peasant woman, and Alfredo (Robert De Niro), the son of the lord of the manor (Burt Lancaster), both born on the same day, 27 January 1901, through to Italy’s Liberation Day, 25 April 1945. Often bombastic and didactic, it enters greatness in the last 30 minutes.

Luna (1979) was the story of a passionate mother/son relationship, in which an internationally renowned opera singer (Jill Clayburgh) has an almost incestuous relationship with her spoiled teenage son who is searching for a father. Bertolucci’s virtuosity is undeniable in the film, which threads together a series of splendid scenes (or arias and duets) on the string of an opaque plot.

The Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man (1981) was Bertolucci’s first film to deal with contemporary Italy since 1964. The elliptical, quasi-thriller tells of a factory owner and self-made man (Ugo Tognazzi), who sees his son being forcibly hustled into a car. The police suspect the victim of colluding in his own kidnapping because of his far left sympathies. The reverse of the Spider’s Stratagem, in which a son investigates his father’s life, this ambiguous view of terrorism failed to please the public and critics mainly because the crime is not solved.

It was six years before Bertolucci was able to make another film. In the meantime, he wrote two screenplays based on Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest, which he hoped would be his first film set in America. When nothing came of it, he went to China to shoot The Last Emperor in English. It was the first western film to be made almost entirely in China with active official Chinese participation. The biopic of Pu Yi, China’s last emperor or “Son of Heaven” who is “re-educated” by the Maoist regime, is a fascinating, sumptuous epic, covering nearly 60 years of China’s cataclysmic history.

Another exploration of the Bertolucci theme of the upper classes learning about working-class life, the film looks every cent of its $21m cost, which included paying for 19,000 extras, 9,000 costumes, and 2,000 kilos of pasta for the Italian crew. Especially impressive was Storaro’s luminous photography, capturing the golden splendour of the palace in the Forbidden City.

After his two-year sojourn in China, Bertolucci completed what he called his “eastern trilogy”, his exploration of non-western cultures, which opened up his work to existential and philosophical themes: The Sheltering Sky (1990), shot in Algeria, Morocco and Niger, and Little Buddha (1993), shot in Bhutan and Nepal.

The former, based on Paul Bowles’ mystical, metaphysical semi-autobiographical novel, followed an egocentric American couple travelling to find the meaning in their relationship. Bertolucci felt that The Sheltering Sky had much in common with Last Tango in Paris. “Isn’t the empty flat of Last Tango a kind of desert and isn’t the desert an empty flat?” he asked. But despite the beautifully captured arid landscapes, the film itself was dramatically arid.

Little Buddha sets the ancient tale of Siddartha (Keanu Reeves) and his quest for enlightenment alongside a contemporary story of an eight-year-old American boy who may be the reincarnation of a famous Buddhist master. The film, which contrasts the two worlds by underlining the blue tonality of Seattle and the red and gold of the oriental story, was aimed at children, though it was more simplistic than simple, and pleased neither children nor adults.

After his expensive, exotic enterprises, Bertolucci returned to home ground, working on a smaller, more intimate scale with Stealing Beauty (1996), a minor piece about a teenage American girl’s sexual awakening at a villa in Tuscany, inhabited by artists and bohemians, and Besieged (1998), set in Rome, which focuses on the relationship between a reclusive English pianist and his young African housekeeper. Made originally for Italian television, Besieged gave Bertolucci a chance to rediscover a kind of spontaneity in film-making which he felt he had lost since the 1960s.

Bertolucci then tried to recapture the spirit of the student uprising in Paris in 1968 in The Dreamers (2003), but its events provide only a background to a cloistered ménage-a-trois whose main preoccupations are sex and the movies. Paying homage to Jean Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles, the film is the apotheosis of Bertolucci’s cinephilia, always an element in his films.

Owing to serious back problems, he used a wheelchair and did not make another film for nine years. Me and You (2012), his first Italian movie since 1981, was a relatively modest affair with a small cast and largely one location – a cellar in which a teenage boy is holed up with his half-sister.

Bertolucci is survived by his second wife, the screenwriter and director Clare Peploe, whom he married in 1978. His first marriage, to the actor Adriana Asti, the female lead in Before the Revolution, ended in divorce.

• Bernardo Bertolucci, film director, born 16 March 1941; died 26 November 2018

Mon 26 Nov 2018

Having already made a reputation as one of the greatest Italian film directors of his generation, Bernardo Bertolucci, who has died aged 77, gained worldwide notoriety with Last Tango in Paris (1972), mainly as a result of its explicit sex scenes. In his depiction of the painful, loveless, joyless relationship between a middle-aged American man (Marlon Brando) and a young Frenchwoman (Maria Schneider), Bertolucci set out to show, he said, that “every sexual relationship is condemned”.

Fifteen years later, Bertolucci gained his greatest international triumph with The Last Emperor (1987), which won nine Oscars. According to Bertolucci, cinema is “a truly poetic language”, a claim that many of his films justify. He had started out as a poet, with his collection In Cerca del Mistero (In Search of Mystery) winning the Viareggio prize in 1962, as his father had done before him.

He was the son of Attilio Bertolucci, a well-known Italian poet, and Ninetta (nee Giovanardi), a school teacher. As a boy Bernardo often accompanied his father to the cinema in Parma, the city where he was born and brought up, and began making 16mm films when he was 16 years old. He got to know the poet Pier Paolo Pasolini through his father, and when Pasolini made his first film, Accatone (1961), Bernardo was hired as production assistant.

A year later he directed his first feature, The Grim Reaper (La Commare Secca), based on a five-page story outline by Pasolini. It told of an investigation into the murder of a prostitute in Rome, seen from different perspectives of different people on the events of her last day. Each episode, as told to the unseen investigator, was filmed in a different style. It is, as the director admitted, the film of “someone who had never shot one foot of 35mm before but who had seen lots and lots of films”.

Before the Revolution (1964), a far more personal film, explores the problems of a selfish middle-class young man who is torn between radical politics and conformity, and between a passionate affair with his young aunt and bourgeois marriage. He opts for respectability on both counts. The film, loosely based on Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, is technically impressive, as is Bertolucci’s ability to articulate themes, such as the betrayal of a totemic father and the connection of the libido with politics, that would mature in his later work. However, as with the film’s hero, there is an element of the dilettante in Bertolucci’s approach.

This impression grew stronger in Partner (1968), which is an undigested homage to Jean-Luc Godard, about a young man literally divided into two by having a double. Derived from Dostoevsky’s short novel The Double, and updated to the Rome of 1968, it has the central character, played by Pierre Clémenti, speaking French while all the rest speak Italian. In the same year, Bertolucci was credited with the story of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West.

Bertolucci’s reputation was greatly enhanced when he joined forces with the cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who had been a camera operator on Before the Revolution. The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), the first of eight films they made together as director and director of photography, easily transposed the Jorge Luis Borges story Theme of the Traitor and the Hero from Ireland to Italy. As oedipal and labyrinthine as its source, it concerns a young man who revisits the village in the Po valley where his father was murdered by the fascists in 1936, and gradually discovers that his father, whom he had considered a hero, was really a traitor.

The Conformist (1970) most successfully brings together Bertolucci’s Freudian and political preoccupations in an ironic study of pre-war Italy (beautifully captured by Storaro) and an attempt to penetrate the mind of ordinary fascism. The childhood trauma of having shot a chauffeur who tried to seduce him, together with his own repressed homosexuality, is a strong factor in making Marcello (Jean-Louis Trintignant) contract a bourgeois marriage and offer his services to the fascist party, for whom he is asked to assassinate his former professor. The Conformist saw the full flowering of Bertolucci’s flamboyant style – elaborate tracking shots, baroque camera angles, opulent colour effects, ornate décor and the intricate play of light and shadow that give his work such a distinctive surface.

After the release of Last Tango in Paris in Europe, Bertolucci was indicted by a court in Bologna for making a pornographic film. Although he was acquitted, he lost his civil rights (including his right to vote) for five years and the Italian courts ordered that all copies of the film should be destroyed. In recent years, further controversy surrounded the extent to which Schneider had consented to elements of the film shoot.

The worldwide acclaim and box office for Last Tango in Paris helped Bertolucci obtain the vast financial resources needed to embark on the long-planned project 1900. With this $6m, five-hour epic, released in 1977, Bertolucci turned away from the introspection of his previous films and tried to make a popular movie of the class struggle using the style of both American epics and the socialist realism of the Russian cinema of the 30s. Italian history is seen through the diverging lives of Olmo (Gérard Depardieu), the son of a peasant woman, and Alfredo (Robert De Niro), the son of the lord of the manor (Burt Lancaster), both born on the same day, 27 January 1901, through to Italy’s Liberation Day, 25 April 1945. Often bombastic and didactic, it enters greatness in the last 30 minutes.

Luna (1979) was the story of a passionate mother/son relationship, in which an internationally renowned opera singer (Jill Clayburgh) has an almost incestuous relationship with her spoiled teenage son who is searching for a father. Bertolucci’s virtuosity is undeniable in the film, which threads together a series of splendid scenes (or arias and duets) on the string of an opaque plot.

The Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man (1981) was Bertolucci’s first film to deal with contemporary Italy since 1964. The elliptical, quasi-thriller tells of a factory owner and self-made man (Ugo Tognazzi), who sees his son being forcibly hustled into a car. The police suspect the victim of colluding in his own kidnapping because of his far left sympathies. The reverse of the Spider’s Stratagem, in which a son investigates his father’s life, this ambiguous view of terrorism failed to please the public and critics mainly because the crime is not solved.

It was six years before Bertolucci was able to make another film. In the meantime, he wrote two screenplays based on Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest, which he hoped would be his first film set in America. When nothing came of it, he went to China to shoot The Last Emperor in English. It was the first western film to be made almost entirely in China with active official Chinese participation. The biopic of Pu Yi, China’s last emperor or “Son of Heaven” who is “re-educated” by the Maoist regime, is a fascinating, sumptuous epic, covering nearly 60 years of China’s cataclysmic history.

Another exploration of the Bertolucci theme of the upper classes learning about working-class life, the film looks every cent of its $21m cost, which included paying for 19,000 extras, 9,000 costumes, and 2,000 kilos of pasta for the Italian crew. Especially impressive was Storaro’s luminous photography, capturing the golden splendour of the palace in the Forbidden City.

After his two-year sojourn in China, Bertolucci completed what he called his “eastern trilogy”, his exploration of non-western cultures, which opened up his work to existential and philosophical themes: The Sheltering Sky (1990), shot in Algeria, Morocco and Niger, and Little Buddha (1993), shot in Bhutan and Nepal.

The former, based on Paul Bowles’ mystical, metaphysical semi-autobiographical novel, followed an egocentric American couple travelling to find the meaning in their relationship. Bertolucci felt that The Sheltering Sky had much in common with Last Tango in Paris. “Isn’t the empty flat of Last Tango a kind of desert and isn’t the desert an empty flat?” he asked. But despite the beautifully captured arid landscapes, the film itself was dramatically arid.

Little Buddha sets the ancient tale of Siddartha (Keanu Reeves) and his quest for enlightenment alongside a contemporary story of an eight-year-old American boy who may be the reincarnation of a famous Buddhist master. The film, which contrasts the two worlds by underlining the blue tonality of Seattle and the red and gold of the oriental story, was aimed at children, though it was more simplistic than simple, and pleased neither children nor adults.

After his expensive, exotic enterprises, Bertolucci returned to home ground, working on a smaller, more intimate scale with Stealing Beauty (1996), a minor piece about a teenage American girl’s sexual awakening at a villa in Tuscany, inhabited by artists and bohemians, and Besieged (1998), set in Rome, which focuses on the relationship between a reclusive English pianist and his young African housekeeper. Made originally for Italian television, Besieged gave Bertolucci a chance to rediscover a kind of spontaneity in film-making which he felt he had lost since the 1960s.

Bertolucci then tried to recapture the spirit of the student uprising in Paris in 1968 in The Dreamers (2003), but its events provide only a background to a cloistered ménage-a-trois whose main preoccupations are sex and the movies. Paying homage to Jean Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles, the film is the apotheosis of Bertolucci’s cinephilia, always an element in his films.

Owing to serious back problems, he used a wheelchair and did not make another film for nine years. Me and You (2012), his first Italian movie since 1981, was a relatively modest affair with a small cast and largely one location – a cellar in which a teenage boy is holed up with his half-sister.

Bertolucci is survived by his second wife, the screenwriter and director Clare Peploe, whom he married in 1978. His first marriage, to the actor Adriana Asti, the female lead in Before the Revolution, ended in divorce.

• Bernardo Bertolucci, film director, born 16 March 1941; died 26 November 2018

Tuesday 27 November 2018

Los Lobos at The Filmore, Chapter 20

Perdiccas

San Francisco

Sunday 25 November 2018

David Hidalgo missed Friday night with a bad back, so Friday was the Cesar Rosas show. They flew in accordion maestro Josh Baca from Texas to fill out the band and enable the Tex-Mex part of the show.

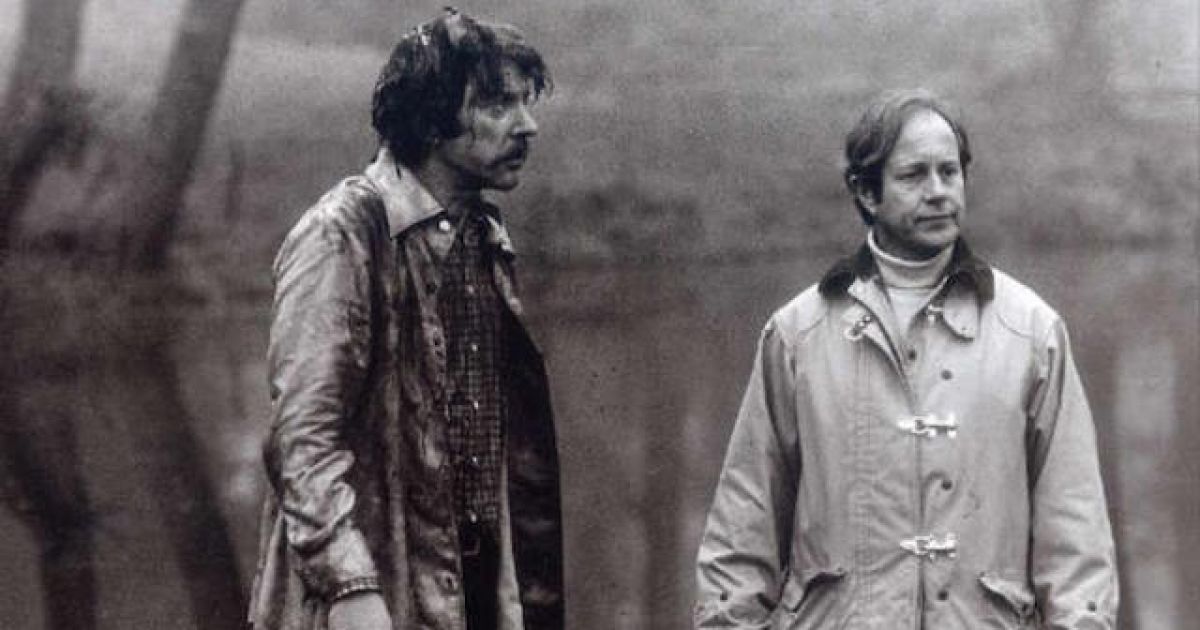

Hidalgo was back for Saturday - see photo - but Josh Baca stayed on, so it was an even more eclectic mix.

Talking to their roadie after the gig, Hidalgo has only missed six shows ever. Unbelievably, I saw one of them, in Austin this year.

They had been nervous before Friday, unsure as to how a set of only Cesar’s blues rockers would go down. Bit of a cliche, but they pulled it off.

Saturday was normal Los Lobos, ending with a 15 minute “Bertha” and encore with the Blasters song “Marie Marie”.

These shows were a double header with L.A. punk band X, now in their 40th year. X were very loud.

Roll on next year...

Saturday was normal Los Lobos, ending with a 15 minute “Bertha” and encore with the Blasters song “Marie Marie”.

These shows were a double header with L.A. punk band X, now in their 40th year. X were very loud.

Roll on next year...

Ah, but there's more...

Monday 26 November 2018

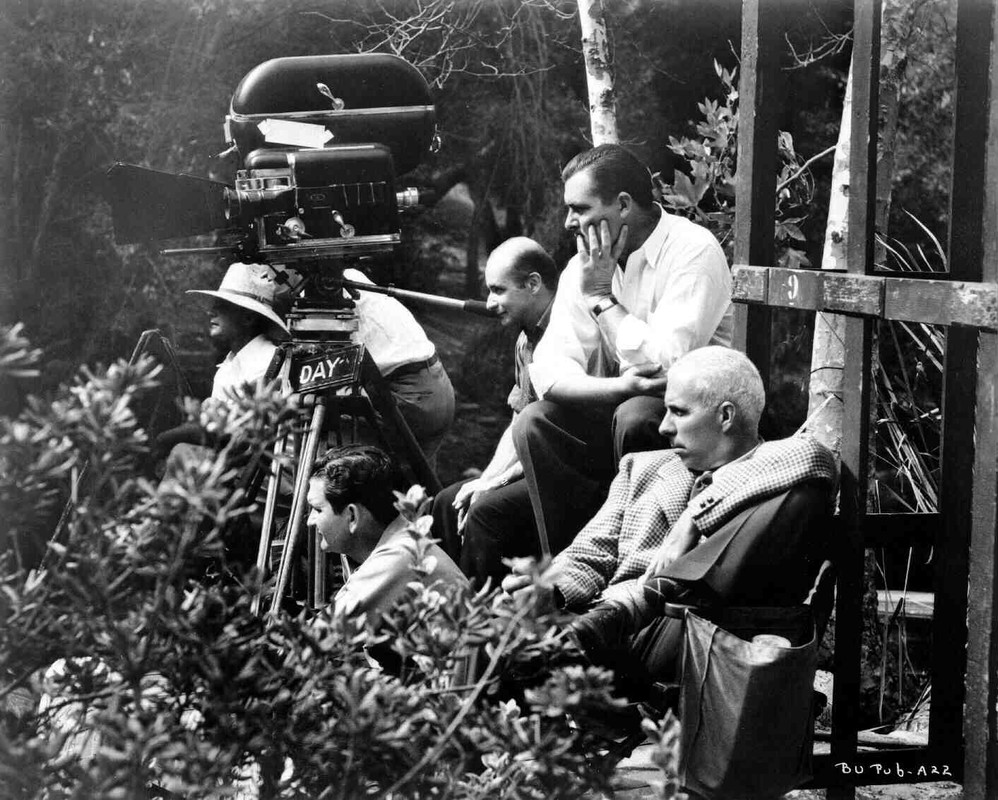

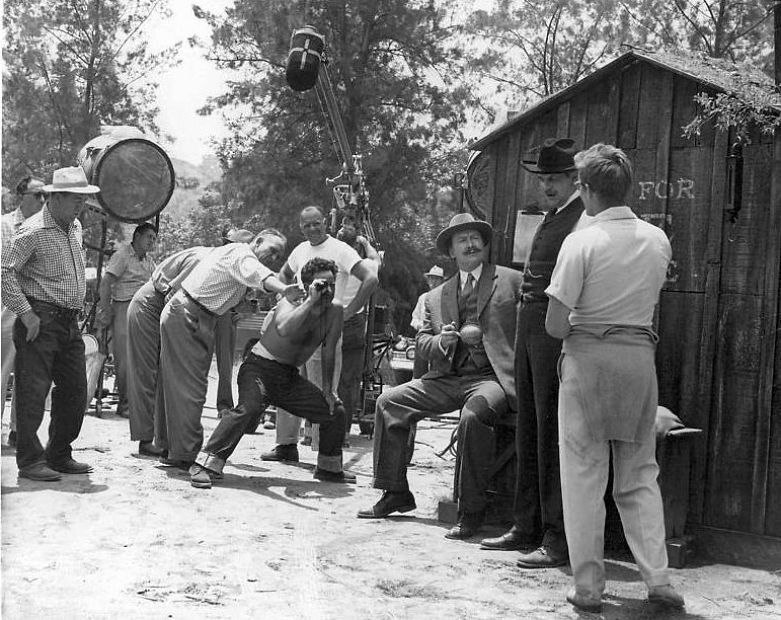

Nic Roeg RIP

Roeg will be remembered for a clutch of masterly films – including Don’t Look Now, the best scary movie of all time, and the unclassifiable Man Who Fell to Earth

Peter Bradshaw

The Guardian

Sat 24 Nov 2018

Afew years ago I wrote to Nic Roeg, explaining that I was working on a talk for the radio about his 1973 masterpiece Don’t Look Now, the story of how a couple’s dead child appears to make contact with them in the eerily dark and echoing waterways of Venice. He invited me to tea at his west London house – the elegant neighbourhood, incidentally, of his 1970 film Performance. We got on to the subject of the unspeakably painful “death” scene at the beginning in which the young daughter of Laura and John, the couple played by Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, drowns in a garden pond while wearing the red anorak to which she is greatly attached.

As I was about to talk about symbolism, Roeg interrupted to tell me that while shooting, that little girl’s father had been in attendance, and every time he called “Action” and the girl sank below the water’s surface, this man could not stop himself jumping into the water to save her. No matter how vehemently Roeg assured him it was safe, he just jumped in, again and again. To get the shot, this man almost had to be physically restrained. It was just too real, too painful, too terrifying. Anyone who has seen the film can understand: the fear and the grief are agonisingly real, despite the irrational chill that attends John’s telepathic sense that something is wrong before the event. I can close my eyes now and see Sutherland, crying out in agony, as he heaves his daughter’s dead body out of the water: it is an image as memorable, more memorable, than the famous sex scene or the supernatural encounters in Venice. Roeg’s films, for all their formal daring, their dreamlike and exotic inventions, their narrative-order experiments, were passionate and visceral. You could compare him, at various stages in his career, to Hitchcock and Kubrick – but Roeg was candid about sex and human relationships in a way that they weren’t.

The great sex scene in the Venice hotel room between Christie and Sutherland (invented by Roeg: it does not exist in the Daphne du Maurier short story it was based on) in which scenes of their lovemaking are disorientatingly mixed in with scenes of them dressing afterwards, is one of his great coups. It is intensely erotic, interspersing the languorous aftermath into the sex like a kind of inverted foreplay. And it is a rare example, maybe the only example, of a movie sex scene in which the participants are not having sex for the first time. (Although it is the first lovemaking since their child’s death.) This is sex between two people who know each other very well. And Christie and Sutherland are for me the most convincing married couple in screen history. Only a film-maker of Roeg’s delicacy and humanity could have created such emotional reality in the middle of a scary movie.

Don’t Look Now was part of an incredible stretch of great films for Roeg who, after a career in cinematography which would have been quite enough for most mortals, came to directing remarkably late: Performance (1970) Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Bad Timing (1980). And even after that he continued to make excellent movies, including Insignificance (1985), the Terry Johnson-scripted fantasy of Marilyn Monroe meeting Albert Einstein, Track 29 (1988), the sensually charged Dennis Potter drama with Gary Oldman and Roeg’s partner Theresa Russell, and his Roald Dahl fantasy The Witches (1990) with Anjelica Huston.

Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell) is an extraordinary film which only gets more extraordinary as time goes by: it is a vivid time capsule of the experimental bohemianism of the late 60s and early 70: a gangster movie, a crime movie, a movie by and for freaks that plugged into the zeitgeist just as it was getting blearier and more cynical. James Fox is the London gangster who holes up in the west London pad of the reclusive rock star played by Mick Jagger. The spiritual cousin of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), Performance was a freewheeling, free-thinking road movie which stayed put and journeyed into the mind’s dark interior.

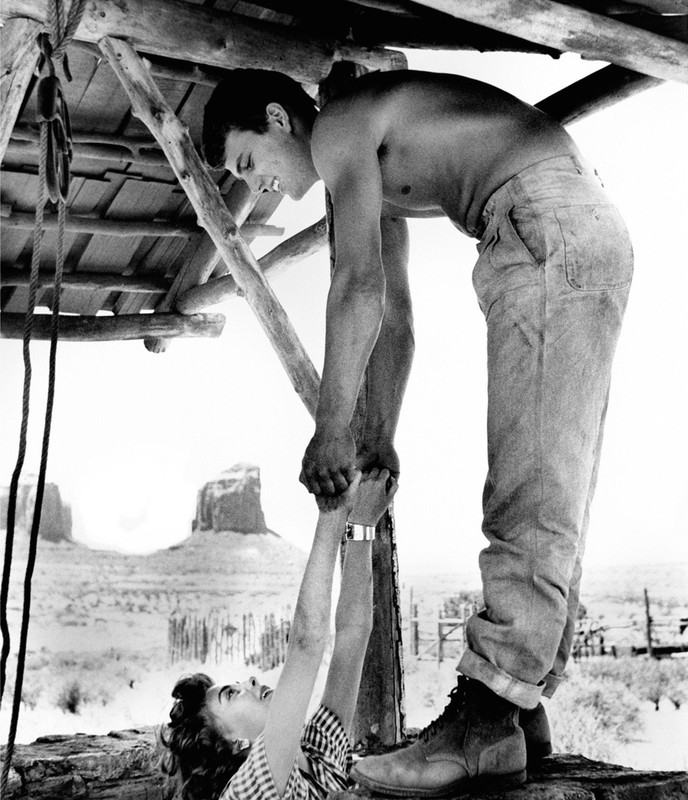

His Walkabout (1971) was another sexually and spiritually dangerous movie, an Australian new wave gem which deserves to be continually revived on screens big and small, but somehow isn’t: the story of two children who are left alone in the outback and befriend an Indigenous Australian boy who helps them survive. Roeg also here deserves to be noted for working with the great dramatist Edward Bond, and seeing how Bond’s rarely employed brilliance could supercharge the movies.

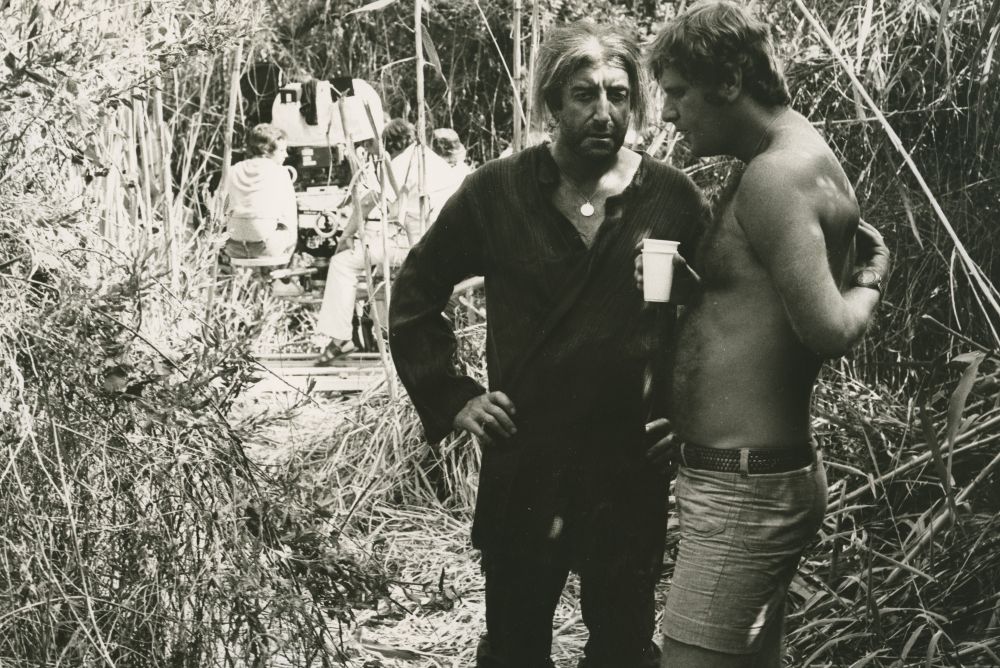

Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) was another unclassifiable, generically unlocatable masterpiece, a film which like Performance harnessed the charisma of a rock god: in this case David Bowie. It is a glorious concept album of a film, or a hyper-evolved midnight movie cult classic in the manner of Roger Corman, with something of 2001. Bowie is the intergalactic visitor to Earth on a mission to save his own stricken planet. The scene in which he faints and has to be carried into his hotel room has a bizarre, fetishistic eroticism that no other director could even guess at.

Bad Timing (1980) is another toweringly transgressive and challenging masterpiece from Roeg, something that at the time upset moralists and thrilled cinephiles (who were also, perhaps, secretly upset as well). Maybe now is the time for cinemas to re-release it in a double bill with Douglas Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession (1954). It also reminds me a little of Dennis Potter’s chilling play Brimstone and Treacle — and at a further remove, of Almodovar’s Talk to Her. Art Garfunkel plays an American psychiatrist who has conceived an obsession with a beautiful American woman played by Theresa Russell. The agony of their relationship is revealed in disordered scenes. The title of the movie may be an ironic comment on Roeg’s audacious attitude to storytelling, or to the tragic fault in our lives generally: the times being out of joint.

And as if that wasn’t enough for us all, he produced a later gem which some consider to be his greatest, and certainly most underrated film: Eureka, in 1983, based on the mysterious true-crime case of Sir Harry Oakes, the fabulously wealthy goldmine owner murdered in his luxurious home. Roeg cast Gene Hackman as the plutocrat whose wealth has somehow transmuted in his mind, through an anti-alchemy of greed and paranoia, into an unending fear that everyone wants to take his money. Eureka is a brilliant Jonsonian parable of human misery.

What an extraordinary film-maker Nic Roeg was, a man whose imagination and technique could not be confined to conventional genres. He should be remembered for a clutch of masterly films, but perhaps especially for his classic Don’t Look Now, not merely the best scary movie in history, but one infused with compassion and love.

Sat 24 Nov 2018

Afew years ago I wrote to Nic Roeg, explaining that I was working on a talk for the radio about his 1973 masterpiece Don’t Look Now, the story of how a couple’s dead child appears to make contact with them in the eerily dark and echoing waterways of Venice. He invited me to tea at his west London house – the elegant neighbourhood, incidentally, of his 1970 film Performance. We got on to the subject of the unspeakably painful “death” scene at the beginning in which the young daughter of Laura and John, the couple played by Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, drowns in a garden pond while wearing the red anorak to which she is greatly attached.

As I was about to talk about symbolism, Roeg interrupted to tell me that while shooting, that little girl’s father had been in attendance, and every time he called “Action” and the girl sank below the water’s surface, this man could not stop himself jumping into the water to save her. No matter how vehemently Roeg assured him it was safe, he just jumped in, again and again. To get the shot, this man almost had to be physically restrained. It was just too real, too painful, too terrifying. Anyone who has seen the film can understand: the fear and the grief are agonisingly real, despite the irrational chill that attends John’s telepathic sense that something is wrong before the event. I can close my eyes now and see Sutherland, crying out in agony, as he heaves his daughter’s dead body out of the water: it is an image as memorable, more memorable, than the famous sex scene or the supernatural encounters in Venice. Roeg’s films, for all their formal daring, their dreamlike and exotic inventions, their narrative-order experiments, were passionate and visceral. You could compare him, at various stages in his career, to Hitchcock and Kubrick – but Roeg was candid about sex and human relationships in a way that they weren’t.

The great sex scene in the Venice hotel room between Christie and Sutherland (invented by Roeg: it does not exist in the Daphne du Maurier short story it was based on) in which scenes of their lovemaking are disorientatingly mixed in with scenes of them dressing afterwards, is one of his great coups. It is intensely erotic, interspersing the languorous aftermath into the sex like a kind of inverted foreplay. And it is a rare example, maybe the only example, of a movie sex scene in which the participants are not having sex for the first time. (Although it is the first lovemaking since their child’s death.) This is sex between two people who know each other very well. And Christie and Sutherland are for me the most convincing married couple in screen history. Only a film-maker of Roeg’s delicacy and humanity could have created such emotional reality in the middle of a scary movie.

Don’t Look Now was part of an incredible stretch of great films for Roeg who, after a career in cinematography which would have been quite enough for most mortals, came to directing remarkably late: Performance (1970) Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Bad Timing (1980). And even after that he continued to make excellent movies, including Insignificance (1985), the Terry Johnson-scripted fantasy of Marilyn Monroe meeting Albert Einstein, Track 29 (1988), the sensually charged Dennis Potter drama with Gary Oldman and Roeg’s partner Theresa Russell, and his Roald Dahl fantasy The Witches (1990) with Anjelica Huston.

Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell) is an extraordinary film which only gets more extraordinary as time goes by: it is a vivid time capsule of the experimental bohemianism of the late 60s and early 70: a gangster movie, a crime movie, a movie by and for freaks that plugged into the zeitgeist just as it was getting blearier and more cynical. James Fox is the London gangster who holes up in the west London pad of the reclusive rock star played by Mick Jagger. The spiritual cousin of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), Performance was a freewheeling, free-thinking road movie which stayed put and journeyed into the mind’s dark interior.

His Walkabout (1971) was another sexually and spiritually dangerous movie, an Australian new wave gem which deserves to be continually revived on screens big and small, but somehow isn’t: the story of two children who are left alone in the outback and befriend an Indigenous Australian boy who helps them survive. Roeg also here deserves to be noted for working with the great dramatist Edward Bond, and seeing how Bond’s rarely employed brilliance could supercharge the movies.

Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) was another unclassifiable, generically unlocatable masterpiece, a film which like Performance harnessed the charisma of a rock god: in this case David Bowie. It is a glorious concept album of a film, or a hyper-evolved midnight movie cult classic in the manner of Roger Corman, with something of 2001. Bowie is the intergalactic visitor to Earth on a mission to save his own stricken planet. The scene in which he faints and has to be carried into his hotel room has a bizarre, fetishistic eroticism that no other director could even guess at.

Bad Timing (1980) is another toweringly transgressive and challenging masterpiece from Roeg, something that at the time upset moralists and thrilled cinephiles (who were also, perhaps, secretly upset as well). Maybe now is the time for cinemas to re-release it in a double bill with Douglas Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession (1954). It also reminds me a little of Dennis Potter’s chilling play Brimstone and Treacle — and at a further remove, of Almodovar’s Talk to Her. Art Garfunkel plays an American psychiatrist who has conceived an obsession with a beautiful American woman played by Theresa Russell. The agony of their relationship is revealed in disordered scenes. The title of the movie may be an ironic comment on Roeg’s audacious attitude to storytelling, or to the tragic fault in our lives generally: the times being out of joint.

And as if that wasn’t enough for us all, he produced a later gem which some consider to be his greatest, and certainly most underrated film: Eureka, in 1983, based on the mysterious true-crime case of Sir Harry Oakes, the fabulously wealthy goldmine owner murdered in his luxurious home. Roeg cast Gene Hackman as the plutocrat whose wealth has somehow transmuted in his mind, through an anti-alchemy of greed and paranoia, into an unending fear that everyone wants to take his money. Eureka is a brilliant Jonsonian parable of human misery.

What an extraordinary film-maker Nic Roeg was, a man whose imagination and technique could not be confined to conventional genres. He should be remembered for a clutch of masterly films, but perhaps especially for his classic Don’t Look Now, not merely the best scary movie in history, but one infused with compassion and love.

Sunday 25 November 2018

Saturday 24 November 2018

John Bluthal RIP

John Bluthal obituary

Stage and screen actor who appeared in popular sitcoms including Never Mind the Quality, Feel the Width and The Vicar of DibleyAnthony Hayward

The Guardian

Mon 19 Nov 2018

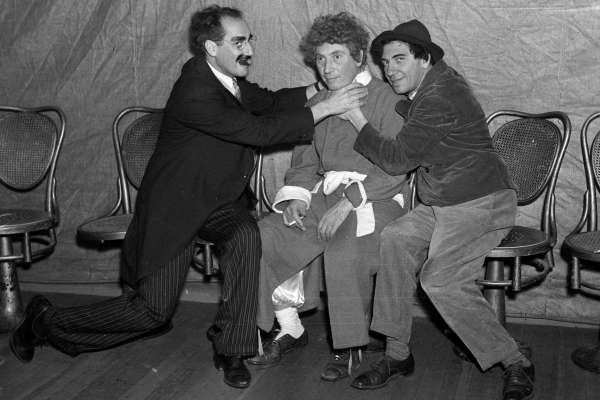

The actor John Bluthal, who has died aged 89, forged a long and successful acting career in Britain that began in the golden age of television in the 1960s, when he provided a foil to the comedy legends Michael Bentine, Eric Sykes, Peter Cook and, over several decades, Spike Milligan.

Bluthal soared to the top of the bill when he starred alongside Joe Lynch in the sitcom Never Mind the Quality, Feel the Width (1967-71), the pair playing respectively the Jewish jacket-maker Manny Cohen and the Irish trouser-maker Patrick Kelly running a business in the East End.

In the series created by Vince Powell and Harry Driver, which had an audience of up to 20 million, Manny sees Patrick as a bigoted Catholic while Patrick regards Manny as an ignorant heathen. Tailoring is the only thing that binds the two men together. There was also a 1973 film spin-off.

Two decades later, Bluthal provided support to Dawn French’s woman priest Geraldine Granger in another popular sitcom, The Vicar of Dibley, created by Richard Curtis. In both series (1994-98) and in various specials until 2013, he played Frank Pickle, the parochial church council secretary at St Barnabas fastidiously taking the minutes. When Pickle comes out as gay after 40 years in the closet, no one hears this revelation because he makes it on a local radio station – and listeners turn off in advance because of his reputation for being boring.

Mon 19 Nov 2018

The actor John Bluthal, who has died aged 89, forged a long and successful acting career in Britain that began in the golden age of television in the 1960s, when he provided a foil to the comedy legends Michael Bentine, Eric Sykes, Peter Cook and, over several decades, Spike Milligan.

Bluthal soared to the top of the bill when he starred alongside Joe Lynch in the sitcom Never Mind the Quality, Feel the Width (1967-71), the pair playing respectively the Jewish jacket-maker Manny Cohen and the Irish trouser-maker Patrick Kelly running a business in the East End.

In the series created by Vince Powell and Harry Driver, which had an audience of up to 20 million, Manny sees Patrick as a bigoted Catholic while Patrick regards Manny as an ignorant heathen. Tailoring is the only thing that binds the two men together. There was also a 1973 film spin-off.

Two decades later, Bluthal provided support to Dawn French’s woman priest Geraldine Granger in another popular sitcom, The Vicar of Dibley, created by Richard Curtis. In both series (1994-98) and in various specials until 2013, he played Frank Pickle, the parochial church council secretary at St Barnabas fastidiously taking the minutes. When Pickle comes out as gay after 40 years in the closet, no one hears this revelation because he makes it on a local radio station – and listeners turn off in advance because of his reputation for being boring.

For another sitcom, Home Sweet Home (1980-82), Bluthal returned to Australia – his home for more than 20 years before settling in Britain – to star as Enzo Pacelli, an Italian immigrant taxi driver. It was another culture-clash comedy, with the ham-fisted Enzo keen to champion his Italian values while his three Australian-educated children embrace the culture of their adopted country.

John was born Isaac Bluthal in the southern Polish town of Jezierzany, in Galicia (now Ozeryany, in Ukraine), to Israel, who worked in the family wheat mill, and Rachel (nee Berman). In 1938, a year before Hitler’s invasion, the nine-year-old Isaac, his sister Nita and their Jewish parents left behind antisemitism in Poland and fled to Australia, where he became known as John.

He was educated at University high school, Melbourne, and showed a talent for accents and impersonations. In 1947, he began training in speech and drama at the Melbourne Conservatorium. Two years later, he appeared at the Budapest youth festival, then moved to London to perform in variety venues and in plays at the Unity theatre.

For several years, he moved between Britain and Australia, before spending the rest of the 1950s building a solid CV in theatres in Melbourne and Sydney. He appeared alongside Bentine in the revue Colored Rhapsody (Tivoli theatre, Melbourne, 1955) and with Leo McKern in The Rainmaker (Elizabethan theatre, Sydney, 1956). Bluthal also performed with Bentine’s fellow Goon Show star Spike Milligan in the 1958 Australian TV special The Gladys Half-Hour and the first two series of The Idiot Weekly (1958-59) on radio.

In 1960, a year after settling in Britain, he played Charlie in the Ray Galton and Alan Simpson-scripted sitcom Citizen James, starring Sid James. He followed this with episodes in the comedy series Sykes and a…(1961), and provided one of the radio voices in the classic Hancock TV series episode The Radio Ham.

He reunited with Bentine in two series of the madcap sketch show It’s a Square World (1961 and 1963) and joined Cook and Dudley Moore in a 1965 episode of Not Only … But Also.

However, Bluthal’s most prolific work with this new generation of groundbreaking writers and performers was alongside Milligan; he was a supporting player in a string of radio programmes, such as The Omar Khayyam Show (1964) and The Milligan Papers (1987), and in TV series including the long-running, surreal sketch show Q… (1969-80), its 1982 sequel, There’s a Lot of It About, and in the series Milligan in … (1972-73). Bluthal and Milligan also appeared on stage together in the satire The Bedsitting Room (Mermaid and Duke of York’s theatres, 1963), written by Milligan and John Antrobus, and in the film The Great McGonagall (1975).

“Working with Spike is agony because he is impetuous and chaotic,” Bluthal explained of Milligan, who was prone to manic depression. Milligan was reputed to have said of his fellow actor: “I love John, but he’s so temperamental.”

On British TV, Bluthal also voiced Commander Wilbur Zero and other characters in Gerry Anderson’s puppet series Fireball XL5 (1962-63). In Australia, he starred as JJ Forbes in the 1981 comedy drama And Here Comes Bucknuckle.

He appeared in many British comedy films of the 60s and 70s, with parts in Carry On productions, the Doctor pictures, and Pink Panther films as well as the Beatles movies A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965). He went to Hollywood for the first time in his mid-80s to play a Marxist professor alongside George Clooney in the film Hail, Caesar! (2016).

However, Bluthal declared theatre to be his first love. He succeeded Ronald Moody in 1961 as Fagin in the original production of Lionel Bart’s hit musical Oliver! in the West End (New theatre) and had many roles with the National Theatre company.

Bluthal returned to Australia to live in Sydney, near his family, in 1999. In 1956, he married the actor and singer Judyth Barron. Although they eventually separated, the couple remained friends; she died in 2016. He is survived by their daughters, Nava, a singer, and Lisa, an actor and singer.

• John Bluthal (Isaac Bluthal), actor, born 12 August 1929; died 15 November 2018

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/nov/19/john-bluthal-obituary

Friday 23 November 2018

Wednesday night's set lists at The Habit, York

He'll Have To Go

Walk Right Back

Ron Elderly: -

Make You Feel My Love

Need Your Love So Bad

You Better Move On

Da Elderly: -

Via Con Dios

I Believe In You

One Of These Days

The Elderly Brothers: -

When Will I Be Loved

The Price Of Love

All My Loving

Then I Kissed Her

I Saw Her Standing There

We ended up running the show as our usual host was poorly and so started off with a couple of songs to open the proceedings. It was very quiet for the first hour or so, so we gave players 3 songs instead of the usual 2 and as others arrived we got through without any hitches.....apart from not getting the reverb unit to work (only one player noticed!!). After my set, kicking off with a Les Paul and Mary Ford classic, I accompanied taxi-driver Chris on Bring It On Home To Me, Birds and Only Love Can Break Your Heart. After closing with some up-tempo Elderlys standards, the audience wanted more, so we continued playing requests (wherever we could) unplugged until closing time. We even played Happy Birthday to an appreciative punter. Great fun!

Thursday 22 November 2018

Tuesday 20 November 2018

The Streets of San Francisco...

Took a walk through the Tenderloin on Saturday, which is horrible. People queuing for food, a lot of them either drunk or stoned, and mainly Black.

The Amtrak ticket clerk was telling me that a few months ago there was a prestigious sales conference in the city and they cleared the streets of homeless to create a better impression. He has recently started driving for Uber to make a bit of extra cash. Demand for Uber is massive here because Twitter and Google are based in the Bay Area and the tech kids have so much money, they will call an Uber to travel two blocks. He says the trickle down economy is working for him.

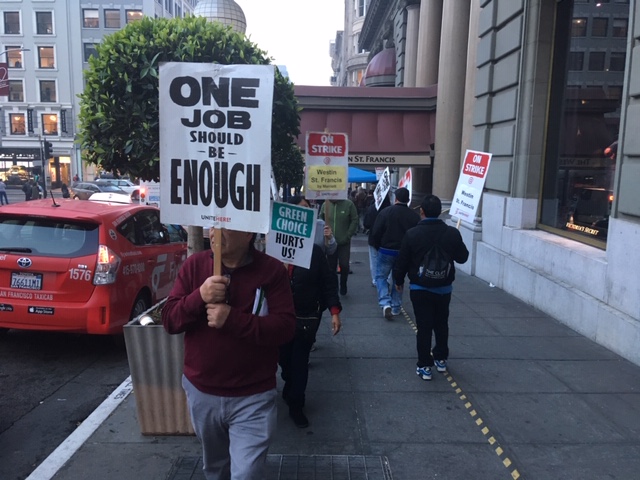

The photo shows striking workers outside the Marriott hotels. Mostly Latino. They were making a hell of a din.

- Perdiccas

Monday 19 November 2018

Sunday 18 November 2018

Saturday 17 November 2018

Burne-Jones at the Tate

Rossetti’s pupil proves his worth with this vivid masterpiece, inspired by his mistress

Skye Sherwin

The Guardian

Fri 2 Nov 2018

Late bloomer …

Created by the young gun who hung around Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s studio absorbing everything he could, this painting, produced between 1870 and 1873, marks a last great flowering of the pre-Raphaelite style: the plight of illicit lovers; the vivid colours; the hallucinogenic detail. It would soon evolve into the flouncy, morally ungrounded aesthetic movement.

Fri 2 Nov 2018

Late bloomer …

Created by the young gun who hung around Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s studio absorbing everything he could, this painting, produced between 1870 and 1873, marks a last great flowering of the pre-Raphaelite style: the plight of illicit lovers; the vivid colours; the hallucinogenic detail. It would soon evolve into the flouncy, morally ungrounded aesthetic movement.

Greece is the word …

The title is from Browning’s poem but the tragic, lovelorn mood is rooted in Burne-Jones’s own life. The woman is inspired by his former mistress, the Greek heiress Maria Zambaco.

Bad romance …

When he painted this 5ft watercolour-cum-gouache the scandalous affair was over. Their elopement had failed and Zambaco had attempted suicide. She would haunt him for the rest of his life, though, occasionally reappearing in his work as an auburn temptress.

The big money …

In 2013, it sold for £14.8m at auction, almost three times its top estimate and the most ever realised for a pre-Raphaelite work.

Edward Burne-Jones, Tate Britain, SW1 to 24 February

Laus Veneris, 1873-78 (Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle)

Tattooed ladies, quick wit and a mystery affair: the other side of Edward Burne-Jones

He’s best known for his ravishing paintings, but the pre-Raphaelite master also loved dashing off quirky sketches of everyday life – and his tubby friend William Morris

Maev Kennedy

His technique was so painstaking that clients waited years or even decades for commissions to be completed. The drawings couldn’t be more different: rapid-fire sketches of daily life, invented characters such as the fat lady, or wicked little caricatures, including the skeletal figure of the artist himself and his friend William Morris, jovially tubby and about to burst his waistcoat buttons. Many were dashed off in letters that he sometimes exchanged up to five times a day with favourite correspondents, often society ladies with whom his precise relationships remain ambiguous.

His friendship with Helen Mary Gaskell apparently began during a dinner party, over shared hilarity at their memories of a famous American tattooed lady, Emma de Burgh. Both were married, Burne-Jones an art-world superstar in his 60s and Gaskell a bored young wife and society hostess. The exact nature of their relationship is unclear, since at her request Burne-Jones destroyed Gaskell’s letters, but Josceline Dimbleby, her great-granddaughter who has written a book about the odd couple, thinks there may have been more to it than pen-friendship. One letter shows Burne-Jones, head in hands, moaning about how dull the day is without her.

A Bathing Beauty c.1893–95

A Bathing Beauty c.1893–95

Gaskell and Burne-Jones had both relished seeing De Burgh, who made a good living for decades exhibiting her spectacularly inked skin, turning to reveal the showstopper: the Last Supper tattooed across her back. Burne-Jones drew De Burgh several times, a sturdy but poised and confident figure, and the exhibition will include his drawing made immediately after seeing her at the London Aquarium.

The illustrated letters to Gaskell are on loan from the Ashmolean in Oxford. The museum acquired them at auction – adding to an extensive collection of exquisite Burne-Jones drawings – but hasn’t previously exhibited them. The letters were a surprising inclusion at the Burlington Fine Arts Society in 1899, where his delicately detailed formal studies for finished paintings were compared to Leonardo da Vinci, but the letters were also admired as examples of his “impassioned imagination”.

“There was definitely some shared interest in fat ladies. It was clearly a private joke between them,” said Colin Harrison, senior curator at the Ashmolean, smiling at a drawing showing an imposing figure, evening gown trailing behind her, barely fitting through the door into a lavatory.

Burne-Jones died of heart failure in 1898, and decades later Gaskell gave the letters to a friend, writing: “If you are like me, you will take them out and laugh when you are an old man, as you did the first time you read them.”

He’s best known for his ravishing paintings, but the pre-Raphaelite master also loved dashing off quirky sketches of everyday life – and his tubby friend William Morris

Maev Kennedy

The Guardian

Thu 18 Oct 2018

It was the high-minded and noble Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones who painted all those armoured knights palely loitering and yearning over wan maidens. It was clearly his scurrilous and much jollier alter ego Ned Jones – his birth name before he upcycled it to a grander version at university – who drew the fat ladies luxuriously dozing in hammocks or sprawled contentedly across chaise longues.

The drawings will go on public display among scores of the pre-Raphaelite artist’s more exalted paintings, in a major exhibition – his first solo show since 1933 – opening next week at Tate Britain. They should delight his admirers, and surprise the many who have been tempted to snap, “Oh pull yourself together man!” in his day – when his graceful male nudes were criticised by some for being insufficiently manly – and ever since.

“The great thing about his jokes is that they are actually funny,” said curator Alison Smith.

The exhibition will include works in stained glass, tapestry and painting, images of a fantasy world that the self-taught Burne-Jones imagined in such obsessive detail that he created full-scale models in his studio of suits of armour, jewels, weapons and even the serpentine monster battled by Perseus.

Thu 18 Oct 2018

It was the high-minded and noble Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones who painted all those armoured knights palely loitering and yearning over wan maidens. It was clearly his scurrilous and much jollier alter ego Ned Jones – his birth name before he upcycled it to a grander version at university – who drew the fat ladies luxuriously dozing in hammocks or sprawled contentedly across chaise longues.

The drawings will go on public display among scores of the pre-Raphaelite artist’s more exalted paintings, in a major exhibition – his first solo show since 1933 – opening next week at Tate Britain. They should delight his admirers, and surprise the many who have been tempted to snap, “Oh pull yourself together man!” in his day – when his graceful male nudes were criticised by some for being insufficiently manly – and ever since.

“The great thing about his jokes is that they are actually funny,” said curator Alison Smith.

The exhibition will include works in stained glass, tapestry and painting, images of a fantasy world that the self-taught Burne-Jones imagined in such obsessive detail that he created full-scale models in his studio of suits of armour, jewels, weapons and even the serpentine monster battled by Perseus.

The Baleful Head, c1876 (Southampton City Art Gallery)

His technique was so painstaking that clients waited years or even decades for commissions to be completed. The drawings couldn’t be more different: rapid-fire sketches of daily life, invented characters such as the fat lady, or wicked little caricatures, including the skeletal figure of the artist himself and his friend William Morris, jovially tubby and about to burst his waistcoat buttons. Many were dashed off in letters that he sometimes exchanged up to five times a day with favourite correspondents, often society ladies with whom his precise relationships remain ambiguous.

His friendship with Helen Mary Gaskell apparently began during a dinner party, over shared hilarity at their memories of a famous American tattooed lady, Emma de Burgh. Both were married, Burne-Jones an art-world superstar in his 60s and Gaskell a bored young wife and society hostess. The exact nature of their relationship is unclear, since at her request Burne-Jones destroyed Gaskell’s letters, but Josceline Dimbleby, her great-granddaughter who has written a book about the odd couple, thinks there may have been more to it than pen-friendship. One letter shows Burne-Jones, head in hands, moaning about how dull the day is without her.

Gaskell and Burne-Jones had both relished seeing De Burgh, who made a good living for decades exhibiting her spectacularly inked skin, turning to reveal the showstopper: the Last Supper tattooed across her back. Burne-Jones drew De Burgh several times, a sturdy but poised and confident figure, and the exhibition will include his drawing made immediately after seeing her at the London Aquarium.

The illustrated letters to Gaskell are on loan from the Ashmolean in Oxford. The museum acquired them at auction – adding to an extensive collection of exquisite Burne-Jones drawings – but hasn’t previously exhibited them. The letters were a surprising inclusion at the Burlington Fine Arts Society in 1899, where his delicately detailed formal studies for finished paintings were compared to Leonardo da Vinci, but the letters were also admired as examples of his “impassioned imagination”.

“There was definitely some shared interest in fat ladies. It was clearly a private joke between them,” said Colin Harrison, senior curator at the Ashmolean, smiling at a drawing showing an imposing figure, evening gown trailing behind her, barely fitting through the door into a lavatory.

Burne-Jones died of heart failure in 1898, and decades later Gaskell gave the letters to a friend, writing: “If you are like me, you will take them out and laugh when you are an old man, as you did the first time you read them.”

Friday 16 November 2018

Wednesday night's set lists at The Habit, York

"Get back to the top where you belong!"

Suspicious Minds

The Air That I Breathe

Da Elderly: -

I'm Just A Loser

In The Morning Light

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Boxer

You're Going To Lose That Girl

I'll Be Back

Baby It's You

When A Man Loves A Woman

The bar fluctuated between full and quiet on a very mild night in York. There was sufficient time for some of the early players to get a second spot and a few late-comers went straight on. The Elderly Brothers closed the show with Simon and Garfunkel and Percy Sledge numbers bookending three Beatles' songs.

And now a somewhat late plug for The Elderly Brothers' gig this Saturday night (17th) in The Habit from 9pm till midnight.

Thursday 15 November 2018

Edgar Degas - Passion for Perfection

This critical profile of the impressionist painter focuses on his obsession with technique – and his problematic personal life

Andrew Pulver

The Guardian

Tue 6 Nov 2018

Having chalked up films on Manet, Monet and Renoir, the excellent Exhibition on Screen series now moves on to the fourth great pillar of French impressionism: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, AKA Edgar Degas. Based around the exhibition at the Fitzwilliam museum in Cambridge a year ago (which transferred to Denver Art Museum), this critical profile covers the bases we have come to expect from these film-makers: glowing gallery dolly shots, informed curatorial comment and a nicely packaged biography.

The subtitle – of the original show, as well as the film – was picked to show Degas’ differences from the traditional idea of the dashed-off, hazy-visual nature of impressionism. With his admiration of the classical canon, his insistence on mastering drawing technique, and his refusal to paint outdoors, much is made of the case to treat Degas as an outlier in the movement.

On the other hand, his determination to break down surface polish, his attempt to freeze-frame his pictures’ narratives, and his unremitting repetition of voyeuristic subject matter put him very much at the heart of it. Added to which, his network of relationships – if not actual friendships – with other impressionist luminaries, outlined in the selection of letters included in voiceover show that, artistically at least, he was far from isolated.

The problem with Degas lies in his personal and political life. Very much on the wrong side in the Dreyfus affair, Degas’ outspoken anti-semitism ought – by modern standards – to make him persona non grata, let alone a mass-consumption art figure. The film-makers don’t shy away from the topic, but dwelling on it at longer length would inevitably change the nature of their film. Perhaps that could be the subject of a follow-up.

Tue 6 Nov 2018

Having chalked up films on Manet, Monet and Renoir, the excellent Exhibition on Screen series now moves on to the fourth great pillar of French impressionism: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, AKA Edgar Degas. Based around the exhibition at the Fitzwilliam museum in Cambridge a year ago (which transferred to Denver Art Museum), this critical profile covers the bases we have come to expect from these film-makers: glowing gallery dolly shots, informed curatorial comment and a nicely packaged biography.

The subtitle – of the original show, as well as the film – was picked to show Degas’ differences from the traditional idea of the dashed-off, hazy-visual nature of impressionism. With his admiration of the classical canon, his insistence on mastering drawing technique, and his refusal to paint outdoors, much is made of the case to treat Degas as an outlier in the movement.

On the other hand, his determination to break down surface polish, his attempt to freeze-frame his pictures’ narratives, and his unremitting repetition of voyeuristic subject matter put him very much at the heart of it. Added to which, his network of relationships – if not actual friendships – with other impressionist luminaries, outlined in the selection of letters included in voiceover show that, artistically at least, he was far from isolated.

The problem with Degas lies in his personal and political life. Very much on the wrong side in the Dreyfus affair, Degas’ outspoken anti-semitism ought – by modern standards – to make him persona non grata, let alone a mass-consumption art figure. The film-makers don’t shy away from the topic, but dwelling on it at longer length would inevitably change the nature of their film. Perhaps that could be the subject of a follow-up.

Tuesday 13 November 2018

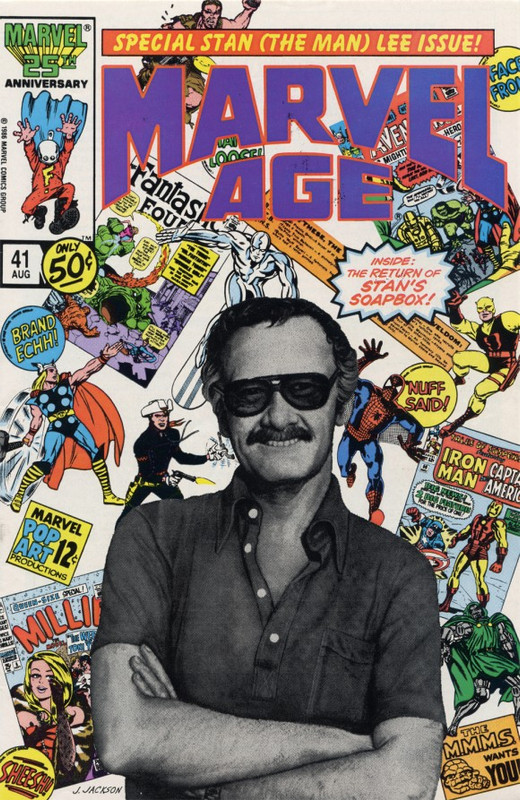

Stan Lee RIP

By Jonathan Kandell and Andy Webster

The New York Times

12 Nov. 2018

If Stan Lee revolutionized the comic book world in the 1960s, which he did, he left as big a stamp — maybe bigger — on the even wider pop culture landscape of today.

Think of “Spider-Man,” the blockbuster movie franchise and Broadway spectacle. Think of “Iron Man,” another Hollywood gold-mine series personified by its star, Robert Downey Jr. Think of “Black Panther,” the box-office superhero smash that shattered big screen racial barriers in the process.

And that is to say nothing of the Hulk, the X-Men, Thor and other film and television juggernauts that have stirred the popular imagination and made many people very rich.

If all that entertainment product can be traced to one person, it would be Stan Lee, who died in Los Angeles on Monday at 95. From a cluttered office on Madison Avenue in Manhattan in the 1960s, he helped conjure a lineup of pulp-fiction heroes that has come to define much of popular culture in the early 21st century.

Mr. Lee was a central player in the creation of those characters and more, all properties of Marvel Comics. Indeed, he was for many the embodiment of Marvel, if not comic books in general, overseeing the company’s emergence as an international media behemoth. A writer, editor, publisher, Hollywood executive and tireless promoter (of Marvel and of himself), he played a critical role in what comics fans call the medium’s silver age.

Many believe that Marvel, under his leadership and infused with his colorful voice, crystallized that era, one of exploding sales, increasingly complex characters and stories, and growing cultural legitimacy for the medium. (Marvel’s chief competitor at the time, National Periodical Publications, now known as DC — the home of Superman and Batman, among other characters — augured this period, with its 1956 update of its superhero the Flash, but did not define it.

Under Mr. Lee, Marvel transformed the comic book world by imbuing its characters with the self-doubts and neuroses of average people, as well an awareness of trends and social causes and, often, a sense of humor.

In humanizing his heroes, giving them character flaws and insecurities that belied their supernatural strengths, Mr. Lee tried “to make them real flesh-and-blood characters with personality,” he told The Washington Post in 1992.

That’s what any story should have, but comics didn’t have until that point,” he said. “They were all cardboard figures.”

Energetic, gregarious, optimistic and alternately grandiose and self-effacing, Mr. Lee was an effective salesman, employing a Barnumesque syntax in print (“Face front, true believer!” “Make mine Marvel!”) to market Marvel’s products to a rabid following.

He charmed readers with jokey, conspiratorial comments and asterisked asides in narrative panels, often referring them to previous issues. In 2003 he told The Los Angeles Times, “I wanted the reader to feel we were all friends, that we were sharing some private fun that the outside world wasn’t aware of.”

Though Mr. Lee was often criticized for his role in denying rights and royalties to his artistic collaborators , his involvement in the conception of many of Marvel’s best-known characters is indisputable.

If Stan Lee revolutionized the comic book world in the 1960s, which he did, he left as big a stamp — maybe bigger — on the even wider pop culture landscape of today.

Think of “Spider-Man,” the blockbuster movie franchise and Broadway spectacle. Think of “Iron Man,” another Hollywood gold-mine series personified by its star, Robert Downey Jr. Think of “Black Panther,” the box-office superhero smash that shattered big screen racial barriers in the process.

And that is to say nothing of the Hulk, the X-Men, Thor and other film and television juggernauts that have stirred the popular imagination and made many people very rich.

If all that entertainment product can be traced to one person, it would be Stan Lee, who died in Los Angeles on Monday at 95. From a cluttered office on Madison Avenue in Manhattan in the 1960s, he helped conjure a lineup of pulp-fiction heroes that has come to define much of popular culture in the early 21st century.

Mr. Lee was a central player in the creation of those characters and more, all properties of Marvel Comics. Indeed, he was for many the embodiment of Marvel, if not comic books in general, overseeing the company’s emergence as an international media behemoth. A writer, editor, publisher, Hollywood executive and tireless promoter (of Marvel and of himself), he played a critical role in what comics fans call the medium’s silver age.

Many believe that Marvel, under his leadership and infused with his colorful voice, crystallized that era, one of exploding sales, increasingly complex characters and stories, and growing cultural legitimacy for the medium. (Marvel’s chief competitor at the time, National Periodical Publications, now known as DC — the home of Superman and Batman, among other characters — augured this period, with its 1956 update of its superhero the Flash, but did not define it.

Under Mr. Lee, Marvel transformed the comic book world by imbuing its characters with the self-doubts and neuroses of average people, as well an awareness of trends and social causes and, often, a sense of humor.

In humanizing his heroes, giving them character flaws and insecurities that belied their supernatural strengths, Mr. Lee tried “to make them real flesh-and-blood characters with personality,” he told The Washington Post in 1992.

That’s what any story should have, but comics didn’t have until that point,” he said. “They were all cardboard figures.”

Energetic, gregarious, optimistic and alternately grandiose and self-effacing, Mr. Lee was an effective salesman, employing a Barnumesque syntax in print (“Face front, true believer!” “Make mine Marvel!”) to market Marvel’s products to a rabid following.

He charmed readers with jokey, conspiratorial comments and asterisked asides in narrative panels, often referring them to previous issues. In 2003 he told The Los Angeles Times, “I wanted the reader to feel we were all friends, that we were sharing some private fun that the outside world wasn’t aware of.”

Though Mr. Lee was often criticized for his role in denying rights and royalties to his artistic collaborators , his involvement in the conception of many of Marvel’s best-known characters is indisputable.

Reading Shakespeare at 10

He was born Stanley Martin Lieber on Dec. 28, 1922, in Manhattan, the older of two sons born to Jack Lieber, an occasionally employed dress cutter, and Celia (Solomon) Lieber, both immigrants from Romania. The family moved to the Bronx.

Stanley began reading Shakespeare at 10 while also devouring pulp magazines, the novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mark Twain, and the swashbuckler movies of Errol Flynn.

He graduated at 17 from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and aspired to be a writer of serious literature. He was set on the path to becoming a different kind of writer when, after a few false starts at other jobs, he was hired at Timely Publications, a company owned by Martin Goodman, a relative who had made his name in pulp magazines and was entering the comics field.

Mr. Lee was initially paid $8 a week as an office gofer. Eventually he was writing and editing stories, many in the superhero genre.

At Timely he worked with the artist Jack Kirby (1917-94), who, with a writing partner, Joe Simon, had created the hit character Captain America, and who would eventually play a vital role in Mr. Lee’s career. When Mr. Simon and Mr. Kirby, Timely’s hottest stars, were lured away by a rival company, Mr. Lee was appointed chief editor.

As a writer, Mr. Lee could be startlingly prolific. “Almost everything I’ve ever written I could finish at one sitting,” he once said. “I’m a fast writer. Maybe not the best, but the fastest.”

Mr. Lee used several pseudonyms to give the impression that Marvel had a large stable of writers; the name that stuck was simply his first name split in two. (In the 1970s, he legally changed Lieber to Lee.)

During World War II, Mr. Lee wrote training manuals stateside in the Army Signal Corps while moonlighting as a comics writer. In 1947, he married Joan Boocock, a former model who had moved to New York from her native England.

His daughter Joan Celia Lee, who is known as J. C., was born in 1950; another daughter, Jan, died three days after birth in 1953. Mr. Lee’s wife died in 2017.

A lawyer for Ms. Lee, Kirk Schenck, confirmed Mr. Lee’s death, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

In addition to his daughter, he is survived by Ms. Lee and his younger brother, Larry Lieber, who drew the “Amazing Spider-Man” syndicated newspaper strip for years.

In the mid-1940s, the peak of the golden age of comic books, sales boomed. But later, as plots and characters turned increasingly lurid (especially at EC, a Marvel competitor that published titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror), many adults clamored for censorship. In 1954, a Senate subcommittee led by the Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver held hearings investigating allegations that comics promoted immorality and juvenile delinquency.

Feeding the senator’s crusade was the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s 1954 anti-comics jeremiad, “Seduction of the Innocent.” Among other claims, the book contended that DC’s “Batman stories” — featuring the team of Batman and Robin — were “psychologically homosexual.”

Choosing to police itself rather than accept legislation, the comics industry established the Comics Code Authority to ensure wholesome content. Gore and moral ambiguity were out, but so largely were wit, literary influences and attention to social issues. Innocuous cookie-cutter exercises in genre were in.

Many found the sanitized comics boring, and — with the new medium of television providing competition — readership, which at one point had reached 600 million sales annually, declined by almost three-quarters within a few years.

With the dimming of superhero comics’ golden age, Mr. Lee tired of grinding out generic humor, romance, western and monster stories for what had by then become Atlas Comics. Reaching a career impasse in his 30s, he was encouraged by his wife to write the comics he wanted to, not merely what was considered marketable. And Mr. Goodman, his boss, spurred by the popularity of a rebooted Flash (and later Green Lantern) at DC, wanted him to revisit superheroes.

Mr. Lee took Mr. Goodman up on his suggestion, but he carried its implications much further.

He was born Stanley Martin Lieber on Dec. 28, 1922, in Manhattan, the older of two sons born to Jack Lieber, an occasionally employed dress cutter, and Celia (Solomon) Lieber, both immigrants from Romania. The family moved to the Bronx.

Stanley began reading Shakespeare at 10 while also devouring pulp magazines, the novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mark Twain, and the swashbuckler movies of Errol Flynn.

He graduated at 17 from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and aspired to be a writer of serious literature. He was set on the path to becoming a different kind of writer when, after a few false starts at other jobs, he was hired at Timely Publications, a company owned by Martin Goodman, a relative who had made his name in pulp magazines and was entering the comics field.

Mr. Lee was initially paid $8 a week as an office gofer. Eventually he was writing and editing stories, many in the superhero genre.

At Timely he worked with the artist Jack Kirby (1917-94), who, with a writing partner, Joe Simon, had created the hit character Captain America, and who would eventually play a vital role in Mr. Lee’s career. When Mr. Simon and Mr. Kirby, Timely’s hottest stars, were lured away by a rival company, Mr. Lee was appointed chief editor.

As a writer, Mr. Lee could be startlingly prolific. “Almost everything I’ve ever written I could finish at one sitting,” he once said. “I’m a fast writer. Maybe not the best, but the fastest.”

Mr. Lee used several pseudonyms to give the impression that Marvel had a large stable of writers; the name that stuck was simply his first name split in two. (In the 1970s, he legally changed Lieber to Lee.)

During World War II, Mr. Lee wrote training manuals stateside in the Army Signal Corps while moonlighting as a comics writer. In 1947, he married Joan Boocock, a former model who had moved to New York from her native England.

His daughter Joan Celia Lee, who is known as J. C., was born in 1950; another daughter, Jan, died three days after birth in 1953. Mr. Lee’s wife died in 2017.

A lawyer for Ms. Lee, Kirk Schenck, confirmed Mr. Lee’s death, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

In addition to his daughter, he is survived by Ms. Lee and his younger brother, Larry Lieber, who drew the “Amazing Spider-Man” syndicated newspaper strip for years.

In the mid-1940s, the peak of the golden age of comic books, sales boomed. But later, as plots and characters turned increasingly lurid (especially at EC, a Marvel competitor that published titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror), many adults clamored for censorship. In 1954, a Senate subcommittee led by the Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver held hearings investigating allegations that comics promoted immorality and juvenile delinquency.

Feeding the senator’s crusade was the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s 1954 anti-comics jeremiad, “Seduction of the Innocent.” Among other claims, the book contended that DC’s “Batman stories” — featuring the team of Batman and Robin — were “psychologically homosexual.”

Choosing to police itself rather than accept legislation, the comics industry established the Comics Code Authority to ensure wholesome content. Gore and moral ambiguity were out, but so largely were wit, literary influences and attention to social issues. Innocuous cookie-cutter exercises in genre were in.

Many found the sanitized comics boring, and — with the new medium of television providing competition — readership, which at one point had reached 600 million sales annually, declined by almost three-quarters within a few years.

With the dimming of superhero comics’ golden age, Mr. Lee tired of grinding out generic humor, romance, western and monster stories for what had by then become Atlas Comics. Reaching a career impasse in his 30s, he was encouraged by his wife to write the comics he wanted to, not merely what was considered marketable. And Mr. Goodman, his boss, spurred by the popularity of a rebooted Flash (and later Green Lantern) at DC, wanted him to revisit superheroes.

Mr. Lee took Mr. Goodman up on his suggestion, but he carried its implications much further.

Enter the Fantastic Four

In 1961, Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby — whom he had brought back years before to the company, now known as Marvel — produced the first issue of The Fantastic Four, about a superpowered team with humanizing dimensions: nonsecret identities, internal squabbles and, in the orange-rock-skinned Thing, self-torment. It was a hit.

Other Marvel titles — like the Lee-Kirby creation The Incredible Hulk, a modern Jekyll-and-Hyde story about a decent man transformed by radiation into a monster — offered a similar template. The quintessential Lee hero, introduced in 1962 and created with the artist Steve Ditko (1927-2018), was Spider-Man.

A timid high school intellectual who gained his powers when bitten by a radioactive spider, Spider-Man was prone to soul-searching, leavened with wisecracks — a key to the character’s lasting popularity across multiple entertainment platforms, including movies and a Broadway musical.

Mr. Lee’s dialogue encompassed Catskills shtick, like Spider-Man’s patter in battle; Elizabethan idioms, like Thor’s; and working-class Lower East Side swagger, like the Thing’s. It could also include dime-store poetry, as in this eco-oratory about humans, uttered by the Silver Surfer, a space alien:

“And yet — in their uncontrollable insanity — in their unforgivable blindness — they seek to destroy this shining jewel — this softly spinning gem — this tiny blessed sphere — which men call Earth!”

Mr. Lee practiced what he called the Marvel method: Instead of handing artists scripts to illustrate, he summarized stories and let the artists draw them and fill in plot details as they chose. He then added sound effects and dialogue. Sometimes he would discover on penciled pages that new characters had been added to the narrative. Such surprises (like the Silver Surfer, a Kirby creation and a Lee favorite) would lead to questions of character ownership.

Mr. Lee was often faulted for not adequately acknowledging the contributions of his illustrators, especially Mr. Kirby. Spider-Man became Marvel’s best-known property, but Mr. Ditko, its co-creator, quit Marvel in bitterness in 1966. Mr. Kirby, who visually designed countless characters, left in 1969. Though he reunited with Mr. Lee for a Silver Surfer graphic novel in 1978, their heyday had ended.

Many comic fans believe that Mr. Kirby was wrongly deprived of royalties and original artwork in his lifetime, and for years the Kirby estate sought to acquire rights to characters that Mr. Kirby and Mr. Lee had created together. Mr. Kirby’s heirs were long rebuffed in court on the grounds that he had done “work for hire” — in other words, that he had essentially sold his art without expecting royalties.

In September 2014, Marvel and the Kirby estate reached a settlement. Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby now both receive credit on numerous screen productions based on their work.

A timid high school intellectual who gained his powers when bitten by a radioactive spider, Spider-Man was prone to soul-searching, leavened with wisecracks — a key to the character’s lasting popularity across multiple entertainment platforms, including movies and a Broadway musical.

Mr. Lee’s dialogue encompassed Catskills shtick, like Spider-Man’s patter in battle; Elizabethan idioms, like Thor’s; and working-class Lower East Side swagger, like the Thing’s. It could also include dime-store poetry, as in this eco-oratory about humans, uttered by the Silver Surfer, a space alien: