Roeg will be remembered for a clutch of masterly films – including Don’t Look Now, the best scary movie of all time, and the unclassifiable Man Who Fell to Earth

Peter Bradshaw

The Guardian

Sat 24 Nov 2018

Afew years ago I wrote to Nic Roeg, explaining that I was working on a talk for the radio about his 1973 masterpiece Don’t Look Now, the story of how a couple’s dead child appears to make contact with them in the eerily dark and echoing waterways of Venice. He invited me to tea at his west London house – the elegant neighbourhood, incidentally, of his 1970 film Performance. We got on to the subject of the unspeakably painful “death” scene at the beginning in which the young daughter of Laura and John, the couple played by Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, drowns in a garden pond while wearing the red anorak to which she is greatly attached.

As I was about to talk about symbolism, Roeg interrupted to tell me that while shooting, that little girl’s father had been in attendance, and every time he called “Action” and the girl sank below the water’s surface, this man could not stop himself jumping into the water to save her. No matter how vehemently Roeg assured him it was safe, he just jumped in, again and again. To get the shot, this man almost had to be physically restrained. It was just too real, too painful, too terrifying. Anyone who has seen the film can understand: the fear and the grief are agonisingly real, despite the irrational chill that attends John’s telepathic sense that something is wrong before the event. I can close my eyes now and see Sutherland, crying out in agony, as he heaves his daughter’s dead body out of the water: it is an image as memorable, more memorable, than the famous sex scene or the supernatural encounters in Venice. Roeg’s films, for all their formal daring, their dreamlike and exotic inventions, their narrative-order experiments, were passionate and visceral. You could compare him, at various stages in his career, to Hitchcock and Kubrick – but Roeg was candid about sex and human relationships in a way that they weren’t.

The great sex scene in the Venice hotel room between Christie and Sutherland (invented by Roeg: it does not exist in the Daphne du Maurier short story it was based on) in which scenes of their lovemaking are disorientatingly mixed in with scenes of them dressing afterwards, is one of his great coups. It is intensely erotic, interspersing the languorous aftermath into the sex like a kind of inverted foreplay. And it is a rare example, maybe the only example, of a movie sex scene in which the participants are not having sex for the first time. (Although it is the first lovemaking since their child’s death.) This is sex between two people who know each other very well. And Christie and Sutherland are for me the most convincing married couple in screen history. Only a film-maker of Roeg’s delicacy and humanity could have created such emotional reality in the middle of a scary movie.

Don’t Look Now was part of an incredible stretch of great films for Roeg who, after a career in cinematography which would have been quite enough for most mortals, came to directing remarkably late: Performance (1970) Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Bad Timing (1980). And even after that he continued to make excellent movies, including Insignificance (1985), the Terry Johnson-scripted fantasy of Marilyn Monroe meeting Albert Einstein, Track 29 (1988), the sensually charged Dennis Potter drama with Gary Oldman and Roeg’s partner Theresa Russell, and his Roald Dahl fantasy The Witches (1990) with Anjelica Huston.

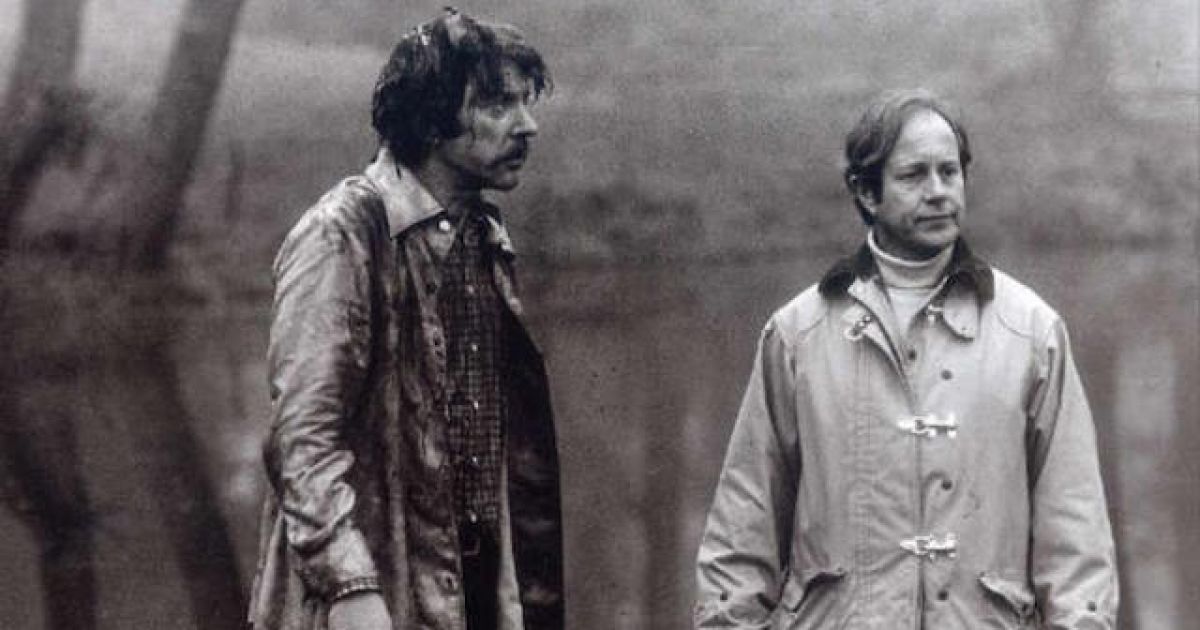

Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell) is an extraordinary film which only gets more extraordinary as time goes by: it is a vivid time capsule of the experimental bohemianism of the late 60s and early 70: a gangster movie, a crime movie, a movie by and for freaks that plugged into the zeitgeist just as it was getting blearier and more cynical. James Fox is the London gangster who holes up in the west London pad of the reclusive rock star played by Mick Jagger. The spiritual cousin of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), Performance was a freewheeling, free-thinking road movie which stayed put and journeyed into the mind’s dark interior.

His Walkabout (1971) was another sexually and spiritually dangerous movie, an Australian new wave gem which deserves to be continually revived on screens big and small, but somehow isn’t: the story of two children who are left alone in the outback and befriend an Indigenous Australian boy who helps them survive. Roeg also here deserves to be noted for working with the great dramatist Edward Bond, and seeing how Bond’s rarely employed brilliance could supercharge the movies.

Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) was another unclassifiable, generically unlocatable masterpiece, a film which like Performance harnessed the charisma of a rock god: in this case David Bowie. It is a glorious concept album of a film, or a hyper-evolved midnight movie cult classic in the manner of Roger Corman, with something of 2001. Bowie is the intergalactic visitor to Earth on a mission to save his own stricken planet. The scene in which he faints and has to be carried into his hotel room has a bizarre, fetishistic eroticism that no other director could even guess at.

Bad Timing (1980) is another toweringly transgressive and challenging masterpiece from Roeg, something that at the time upset moralists and thrilled cinephiles (who were also, perhaps, secretly upset as well). Maybe now is the time for cinemas to re-release it in a double bill with Douglas Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession (1954). It also reminds me a little of Dennis Potter’s chilling play Brimstone and Treacle — and at a further remove, of Almodovar’s Talk to Her. Art Garfunkel plays an American psychiatrist who has conceived an obsession with a beautiful American woman played by Theresa Russell. The agony of their relationship is revealed in disordered scenes. The title of the movie may be an ironic comment on Roeg’s audacious attitude to storytelling, or to the tragic fault in our lives generally: the times being out of joint.

And as if that wasn’t enough for us all, he produced a later gem which some consider to be his greatest, and certainly most underrated film: Eureka, in 1983, based on the mysterious true-crime case of Sir Harry Oakes, the fabulously wealthy goldmine owner murdered in his luxurious home. Roeg cast Gene Hackman as the plutocrat whose wealth has somehow transmuted in his mind, through an anti-alchemy of greed and paranoia, into an unending fear that everyone wants to take his money. Eureka is a brilliant Jonsonian parable of human misery.

What an extraordinary film-maker Nic Roeg was, a man whose imagination and technique could not be confined to conventional genres. He should be remembered for a clutch of masterly films, but perhaps especially for his classic Don’t Look Now, not merely the best scary movie in history, but one infused with compassion and love.

Sat 24 Nov 2018

Afew years ago I wrote to Nic Roeg, explaining that I was working on a talk for the radio about his 1973 masterpiece Don’t Look Now, the story of how a couple’s dead child appears to make contact with them in the eerily dark and echoing waterways of Venice. He invited me to tea at his west London house – the elegant neighbourhood, incidentally, of his 1970 film Performance. We got on to the subject of the unspeakably painful “death” scene at the beginning in which the young daughter of Laura and John, the couple played by Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, drowns in a garden pond while wearing the red anorak to which she is greatly attached.

As I was about to talk about symbolism, Roeg interrupted to tell me that while shooting, that little girl’s father had been in attendance, and every time he called “Action” and the girl sank below the water’s surface, this man could not stop himself jumping into the water to save her. No matter how vehemently Roeg assured him it was safe, he just jumped in, again and again. To get the shot, this man almost had to be physically restrained. It was just too real, too painful, too terrifying. Anyone who has seen the film can understand: the fear and the grief are agonisingly real, despite the irrational chill that attends John’s telepathic sense that something is wrong before the event. I can close my eyes now and see Sutherland, crying out in agony, as he heaves his daughter’s dead body out of the water: it is an image as memorable, more memorable, than the famous sex scene or the supernatural encounters in Venice. Roeg’s films, for all their formal daring, their dreamlike and exotic inventions, their narrative-order experiments, were passionate and visceral. You could compare him, at various stages in his career, to Hitchcock and Kubrick – but Roeg was candid about sex and human relationships in a way that they weren’t.

The great sex scene in the Venice hotel room between Christie and Sutherland (invented by Roeg: it does not exist in the Daphne du Maurier short story it was based on) in which scenes of their lovemaking are disorientatingly mixed in with scenes of them dressing afterwards, is one of his great coups. It is intensely erotic, interspersing the languorous aftermath into the sex like a kind of inverted foreplay. And it is a rare example, maybe the only example, of a movie sex scene in which the participants are not having sex for the first time. (Although it is the first lovemaking since their child’s death.) This is sex between two people who know each other very well. And Christie and Sutherland are for me the most convincing married couple in screen history. Only a film-maker of Roeg’s delicacy and humanity could have created such emotional reality in the middle of a scary movie.

Don’t Look Now was part of an incredible stretch of great films for Roeg who, after a career in cinematography which would have been quite enough for most mortals, came to directing remarkably late: Performance (1970) Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Bad Timing (1980). And even after that he continued to make excellent movies, including Insignificance (1985), the Terry Johnson-scripted fantasy of Marilyn Monroe meeting Albert Einstein, Track 29 (1988), the sensually charged Dennis Potter drama with Gary Oldman and Roeg’s partner Theresa Russell, and his Roald Dahl fantasy The Witches (1990) with Anjelica Huston.

Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell) is an extraordinary film which only gets more extraordinary as time goes by: it is a vivid time capsule of the experimental bohemianism of the late 60s and early 70: a gangster movie, a crime movie, a movie by and for freaks that plugged into the zeitgeist just as it was getting blearier and more cynical. James Fox is the London gangster who holes up in the west London pad of the reclusive rock star played by Mick Jagger. The spiritual cousin of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), Performance was a freewheeling, free-thinking road movie which stayed put and journeyed into the mind’s dark interior.

His Walkabout (1971) was another sexually and spiritually dangerous movie, an Australian new wave gem which deserves to be continually revived on screens big and small, but somehow isn’t: the story of two children who are left alone in the outback and befriend an Indigenous Australian boy who helps them survive. Roeg also here deserves to be noted for working with the great dramatist Edward Bond, and seeing how Bond’s rarely employed brilliance could supercharge the movies.

Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) was another unclassifiable, generically unlocatable masterpiece, a film which like Performance harnessed the charisma of a rock god: in this case David Bowie. It is a glorious concept album of a film, or a hyper-evolved midnight movie cult classic in the manner of Roger Corman, with something of 2001. Bowie is the intergalactic visitor to Earth on a mission to save his own stricken planet. The scene in which he faints and has to be carried into his hotel room has a bizarre, fetishistic eroticism that no other director could even guess at.

Bad Timing (1980) is another toweringly transgressive and challenging masterpiece from Roeg, something that at the time upset moralists and thrilled cinephiles (who were also, perhaps, secretly upset as well). Maybe now is the time for cinemas to re-release it in a double bill with Douglas Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession (1954). It also reminds me a little of Dennis Potter’s chilling play Brimstone and Treacle — and at a further remove, of Almodovar’s Talk to Her. Art Garfunkel plays an American psychiatrist who has conceived an obsession with a beautiful American woman played by Theresa Russell. The agony of their relationship is revealed in disordered scenes. The title of the movie may be an ironic comment on Roeg’s audacious attitude to storytelling, or to the tragic fault in our lives generally: the times being out of joint.

And as if that wasn’t enough for us all, he produced a later gem which some consider to be his greatest, and certainly most underrated film: Eureka, in 1983, based on the mysterious true-crime case of Sir Harry Oakes, the fabulously wealthy goldmine owner murdered in his luxurious home. Roeg cast Gene Hackman as the plutocrat whose wealth has somehow transmuted in his mind, through an anti-alchemy of greed and paranoia, into an unending fear that everyone wants to take his money. Eureka is a brilliant Jonsonian parable of human misery.

What an extraordinary film-maker Nic Roeg was, a man whose imagination and technique could not be confined to conventional genres. He should be remembered for a clutch of masterly films, but perhaps especially for his classic Don’t Look Now, not merely the best scary movie in history, but one infused with compassion and love.

No comments:

Post a Comment