The poet’s sweetly sad dispatches, mostly addressed to his mother, reek of social history, while revealing a witty, wise and grossly impractical man

Rachel Cooke

The Observer

Sunday 4 November 2018

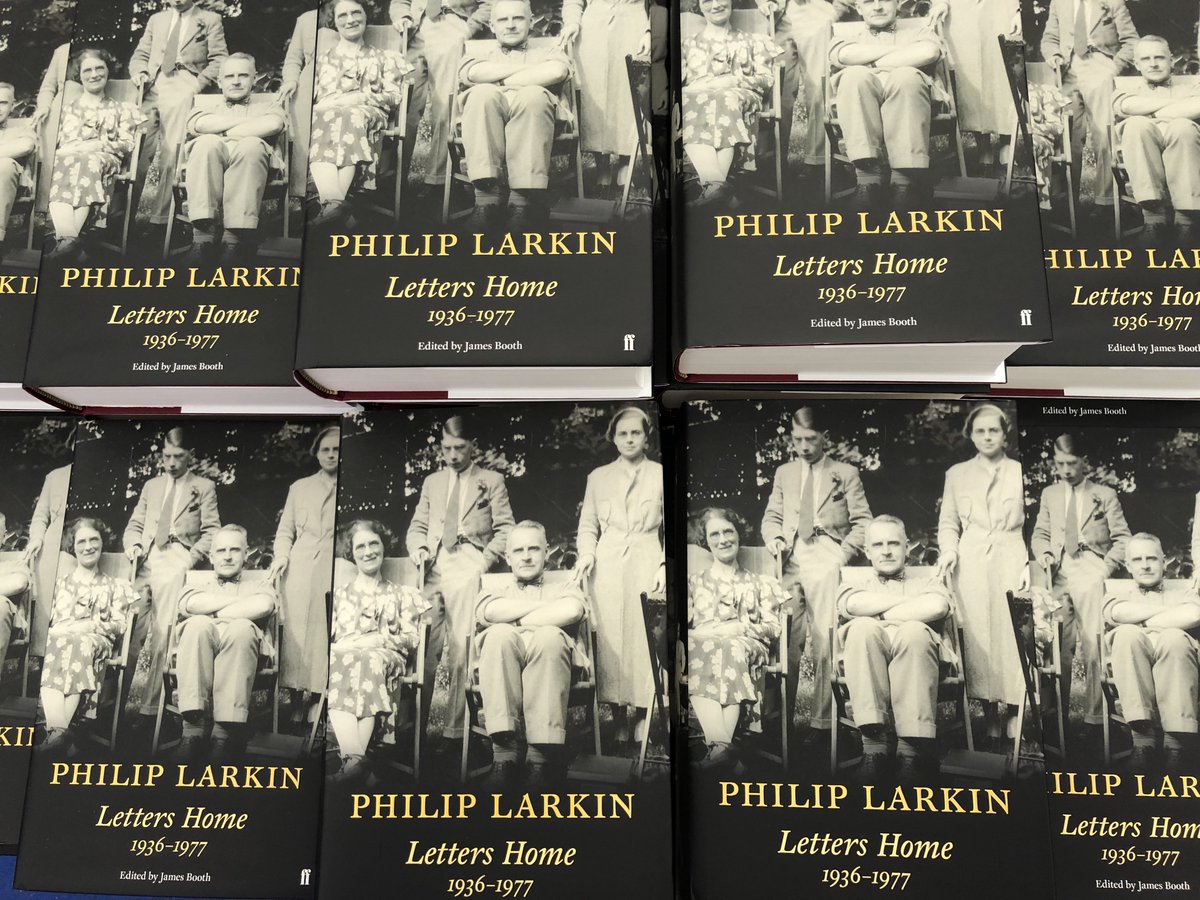

Sometimes, you have to wonder about the guardians of Philip Larkin’s legacy. Deep inside James Booth’s selection of the letters the poet wrote to his family between 1936 and 1977 can be found what is surely one of the weirdest photographs ever to appear between scholarly hard covers. Comprising three pairs of tatty socks – one lilac, one salmon, one navy blue – this motley selection of hosiery, the caption informs us, was “recovered” from the poet’s house in Hull following the death of his girlfriend, Monica Jones, in 2004 (oh, that word, “recovered”: what derring-do it implies). There then follows, by way of an explanation, a line from a note Larkin sent his mother in 1943. “I darned two pairs last Tuesday with great satisfaction,” it reads. “Only not having any khaki wool I had to darn in grey.”

When it comes to Larkin, however, I begin to wonder about myself, too. The majority of these letters are addressed to the poet’s mother, Larkin having written to her every week since he left home, and at least once a day in the last five years of her life. Their subjects include constipation, draught excluders, and the engagement of Princess Anne, and on the surface of it, they could not be more banal. Does anyone really want to hear of Eva Larkin’s endless struggles with chicken carcasses and dodgy tins? (“Have you got the cheese disposed of yet?” he asks in a letter of 1 January 1955, as if cheese were a substance that demanded the wearing of special protective gear). Do we honestly care about her worries over rain clouds, of which she had a morbid fear?

But I found that I did care in the end. This old, brown world of hissing gas fires, strange smells on the stairs, and filial duty worn like some heavy overcoat: how it hypnotises. When I wasn’t crying with laughter – “you can’t expect to enjoy yourself on holiday as you do at home” is among the more Hilda Ogden-ish advice Larkin dispenses to his ma – I was often close to sobbing at the sweet-sadness of it all. Behind the belly-aching and the penny-pinching, the making-do and the clay-cold depression, there is an immensity of kindness here, and the fact that this was sometimes so effortful on Larkin’s part only makes it the more tender (Eva, so anxious she could not sleep in her own house alone, frequently drove her son halfway round the bend).

Though his personal misery may have been deepening all the while, these letters bring to mind not the “coastal shelf” of his most famous poem, but something far softer, and altogether more benevolent. Here, like it or not, is love. It survives him, a better garland by far than a pile of old socks.

Booth, Larkin’s biographer, has edited these letters superbly well (there are 607 in this volume, a mere sliver of the terrifying total in existence), even if his footnotes are pedantic at times. Neatly tracing the poet’s adult life from Oxford University, through Wellington, Leicester and Belfast, where he worked in various libraries, and finally to Hull, a picture of the man slowly emerges. It’s not new, but perhaps the emphasis is slightly altered. Larkin as we find him here is witty, wise, grossly impractical, and extremely modest, in every sense of the word.

“I’m sorry… if your old friends have found out your new address,” he writes to Eva in 1952, a typical example of the way he wraps his (genuine, but weary) concern for her in a drollery she would not have noticed. It’s going to take me a long time to put from my mind the fact that, for his 50th birthday, he asked his sister, Kitty, for nothing more than a plastic container in which he might keep grapefruit juice. Above all, there is something so painfully contingent about his life: the rented rooms, the various triangles formed by various women, his conviction that (as the librarian of Hull University) he was in the wrong job in the wrong place. What part did Eva play in this suspended animation? (Larkin’s father, Sydney, the city treasurer of Coventry, died in 1948.)

Both Jones and another of his lovers, Maeve Brennan, believed that Eva got in the way of Larkin’s relationship with them, and at one point in these letters, Larkin writes expressly of the fact that he must neglect either Eva or Monica over Christmas, and how impossible this is for him.

But it’s too easy to lay his emotional contortions at his mother’s feet. He was deeply loved by her: a gift, however claustrophobic at times, that should have made relationships easier, not more difficult. “When I am in I want to be out, and when I am out I want to be in,” he writes to Eva from Belfast, of his faltering social life.

Larkin was ever uncertain, that’s all, ambivalence stamped on his character like a postmark – and why bemoan it, when it’s from this that the most magnificent and gently shrewd of his poems grow? (Eva inspired, directly or indirectly, several of them: Reference Back, Faith Healing, The Old Fools and the late, great Aubade, completed in days, after her death in November 1977.)

Is there poetry in these letters? Not often, though several poets shuffle and stride across them, from WH Auden to TS Eliot. The call of a blackbird sounds “like a smooth, polished sound-shape cast up on the beach of the evening”; every day arrives like a “newly cellophaned present”.

But he’s such a good writer that he cannot ever be bad – even when he is only tackling the vexed issue of his mother’s linen basket (how I shrieked at the letter in which he carefully thanks her for having washed a certain basque, a “very worthwhile” garment – though not, perhaps, as loudly as when I read the footnote informing me that said basque “must have been Monica’s”).

And what social history is here. You can almost smell it. This is a realm, now entirely disappeared, in which Louis Armstrong plays Bridlington, every posh dinner begins with celery soup, and little girls still keep their bedclothes in nightdress cases, as Kitty once did. It’s like visiting another planet – a chilly one, where the immersion heater is on only very rarely.

Sunday 4 November 2018

Sometimes, you have to wonder about the guardians of Philip Larkin’s legacy. Deep inside James Booth’s selection of the letters the poet wrote to his family between 1936 and 1977 can be found what is surely one of the weirdest photographs ever to appear between scholarly hard covers. Comprising three pairs of tatty socks – one lilac, one salmon, one navy blue – this motley selection of hosiery, the caption informs us, was “recovered” from the poet’s house in Hull following the death of his girlfriend, Monica Jones, in 2004 (oh, that word, “recovered”: what derring-do it implies). There then follows, by way of an explanation, a line from a note Larkin sent his mother in 1943. “I darned two pairs last Tuesday with great satisfaction,” it reads. “Only not having any khaki wool I had to darn in grey.”

When it comes to Larkin, however, I begin to wonder about myself, too. The majority of these letters are addressed to the poet’s mother, Larkin having written to her every week since he left home, and at least once a day in the last five years of her life. Their subjects include constipation, draught excluders, and the engagement of Princess Anne, and on the surface of it, they could not be more banal. Does anyone really want to hear of Eva Larkin’s endless struggles with chicken carcasses and dodgy tins? (“Have you got the cheese disposed of yet?” he asks in a letter of 1 January 1955, as if cheese were a substance that demanded the wearing of special protective gear). Do we honestly care about her worries over rain clouds, of which she had a morbid fear?

But I found that I did care in the end. This old, brown world of hissing gas fires, strange smells on the stairs, and filial duty worn like some heavy overcoat: how it hypnotises. When I wasn’t crying with laughter – “you can’t expect to enjoy yourself on holiday as you do at home” is among the more Hilda Ogden-ish advice Larkin dispenses to his ma – I was often close to sobbing at the sweet-sadness of it all. Behind the belly-aching and the penny-pinching, the making-do and the clay-cold depression, there is an immensity of kindness here, and the fact that this was sometimes so effortful on Larkin’s part only makes it the more tender (Eva, so anxious she could not sleep in her own house alone, frequently drove her son halfway round the bend).

Though his personal misery may have been deepening all the while, these letters bring to mind not the “coastal shelf” of his most famous poem, but something far softer, and altogether more benevolent. Here, like it or not, is love. It survives him, a better garland by far than a pile of old socks.

Booth, Larkin’s biographer, has edited these letters superbly well (there are 607 in this volume, a mere sliver of the terrifying total in existence), even if his footnotes are pedantic at times. Neatly tracing the poet’s adult life from Oxford University, through Wellington, Leicester and Belfast, where he worked in various libraries, and finally to Hull, a picture of the man slowly emerges. It’s not new, but perhaps the emphasis is slightly altered. Larkin as we find him here is witty, wise, grossly impractical, and extremely modest, in every sense of the word.

“I’m sorry… if your old friends have found out your new address,” he writes to Eva in 1952, a typical example of the way he wraps his (genuine, but weary) concern for her in a drollery she would not have noticed. It’s going to take me a long time to put from my mind the fact that, for his 50th birthday, he asked his sister, Kitty, for nothing more than a plastic container in which he might keep grapefruit juice. Above all, there is something so painfully contingent about his life: the rented rooms, the various triangles formed by various women, his conviction that (as the librarian of Hull University) he was in the wrong job in the wrong place. What part did Eva play in this suspended animation? (Larkin’s father, Sydney, the city treasurer of Coventry, died in 1948.)

Both Jones and another of his lovers, Maeve Brennan, believed that Eva got in the way of Larkin’s relationship with them, and at one point in these letters, Larkin writes expressly of the fact that he must neglect either Eva or Monica over Christmas, and how impossible this is for him.

But it’s too easy to lay his emotional contortions at his mother’s feet. He was deeply loved by her: a gift, however claustrophobic at times, that should have made relationships easier, not more difficult. “When I am in I want to be out, and when I am out I want to be in,” he writes to Eva from Belfast, of his faltering social life.

Larkin was ever uncertain, that’s all, ambivalence stamped on his character like a postmark – and why bemoan it, when it’s from this that the most magnificent and gently shrewd of his poems grow? (Eva inspired, directly or indirectly, several of them: Reference Back, Faith Healing, The Old Fools and the late, great Aubade, completed in days, after her death in November 1977.)

Is there poetry in these letters? Not often, though several poets shuffle and stride across them, from WH Auden to TS Eliot. The call of a blackbird sounds “like a smooth, polished sound-shape cast up on the beach of the evening”; every day arrives like a “newly cellophaned present”.

But he’s such a good writer that he cannot ever be bad – even when he is only tackling the vexed issue of his mother’s linen basket (how I shrieked at the letter in which he carefully thanks her for having washed a certain basque, a “very worthwhile” garment – though not, perhaps, as loudly as when I read the footnote informing me that said basque “must have been Monica’s”).

And what social history is here. You can almost smell it. This is a realm, now entirely disappeared, in which Louis Armstrong plays Bridlington, every posh dinner begins with celery soup, and little girls still keep their bedclothes in nightdress cases, as Kitty once did. It’s like visiting another planet – a chilly one, where the immersion heater is on only very rarely.

No comments:

Post a Comment