Tuesday 30 April 2019

Monday 29 April 2019

Sunday 28 April 2019

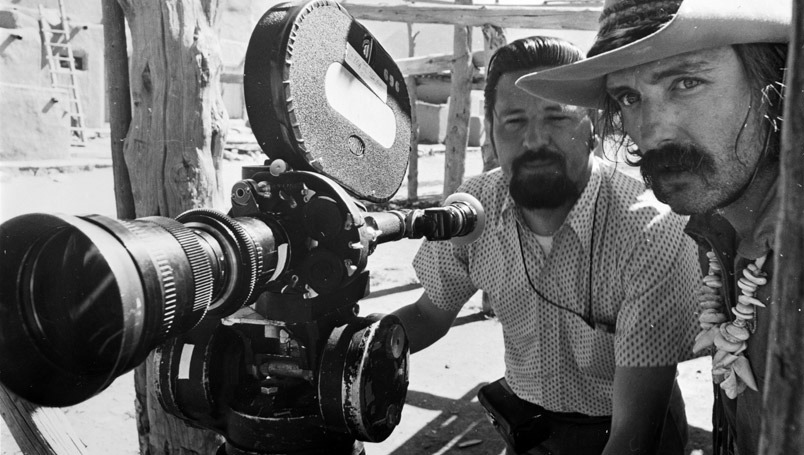

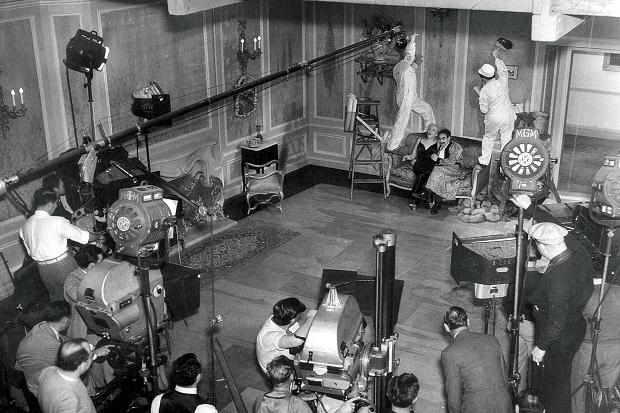

Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition

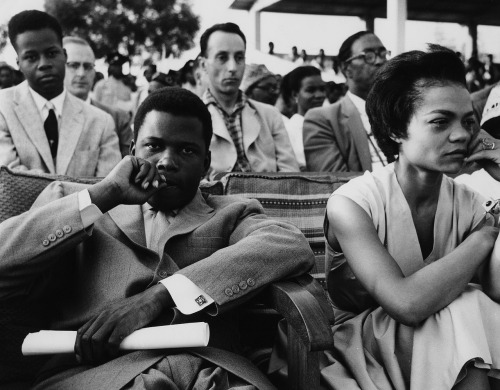

On the set of Full Metal Jacket

Design Museum, London

This astounding exhibition reveals the obsessive level of genius the great director showed, whether inventing the space age – or restaging the Vietnam war in a London gas works

Oliver Wainwright

The Guardian

25 Apr 2019

A photograph of a rambling snow-covered hotel in Oregon is on display in the Design Museum, annotated with the energetic scribbles and emphatic instructions of film director Stanley Kubrick. After sending his set designer to scour America for locations, he had finally settled on the building he would use as the exterior of his haunted hotel in The Shining. Labels stuck liberally across the image explain exactly how he wanted the curving path through the snow to appear in the shot, along with a characteristically stern warning: “THERE IS NO OTHER WAY TO DO IT, REPEAT NO OTHER WAY. Exercise the greatest care as the compositional effect of a different path might be BAD BAD BAD.”

The photograph provides a glimpse of the obsessive attention to detail and relentless perfectionism that Kubrick brought to his films, a method of total control vividly depicted in this new blockbuster exhibition on his life and work. Featuring over 500 objects – from Ken Adam’s sketches for the War Room in Dr Strangelove, to erotic furniture from the Korova Milk Bar in A Clockwork Orange – the show plunges the visitor headlong into Kubrick’s meticulous, and often disturbing, mind, revealing how he constructed entire worlds from scratch to tell his stories.

The first step was always research, and lots of it. Kubrick would spend years immersing himself in the subject at hand until he knew every detail about the characters, events and scientific phenomena he was portraying. As a section on his (unrealised) Napoleon film shows, he produced an index card for every day of the French emperor’s life, with notes about his activities, even down to menu choices. “It was an analogue Wikipedia,” says curator Deyan Sudjic.

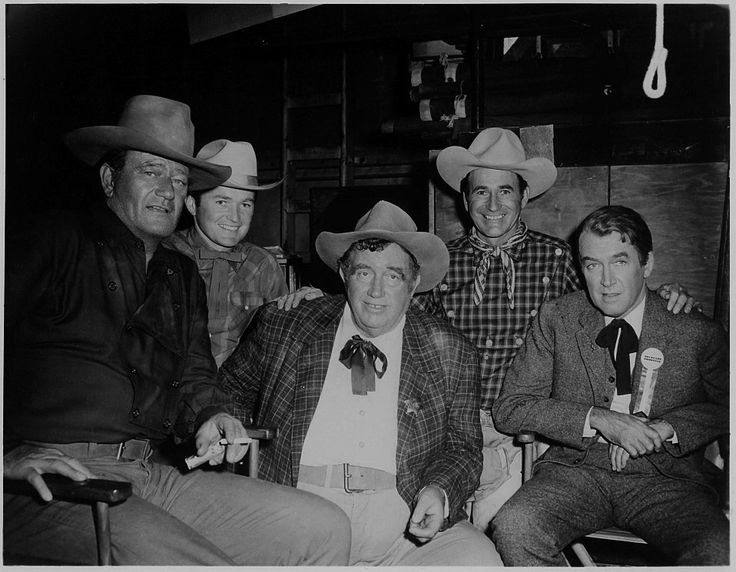

Ken Adam's design for the War Room in Dr Strangelove

Sometimes Kubrick’s level of knowledge would land him in trouble. The interiors of the war planes in Dr Strangelove were so detailed that he was suspected of spying. Production designer Ken Adam recalled that “American military personnel visited the set and were terrified by the amount of accuracy we had in this aircraft. We received a memo saying: ‘You had better make sure you know where your references come from or else you might be investigated by the FBI.’”

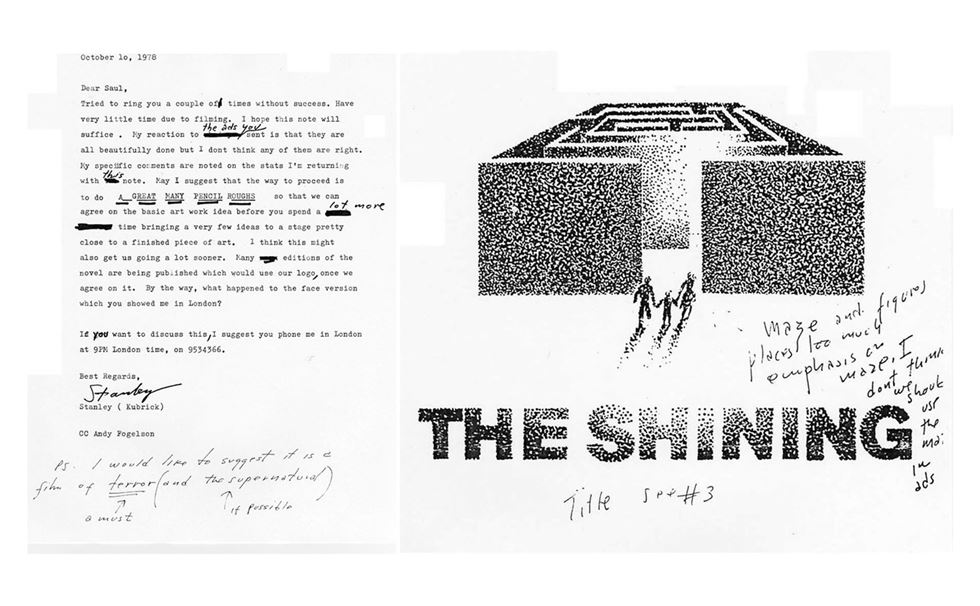

Kubrick's notes on The Shining poster to Saul Bass

Through the reams of correspondence, sketches, props and notes on show, Kubrick emerges as an omnipotent figure, enjoying complete control over every aspect of his productions, from the design of costumes to promotional posters – as well as an enviable ability to extend both deadlines and budgets. Notes show him haranguing Saul Bass over his designs for The Shining poster (“Hard to read, even at this size” … “Hotel looks too sprawling”), and tweaking the fabric choices of Hardy Amies’ costumes for 2001: A Space Odyssey. The genius of the sci-fi film’s design was that it suggested a plausible future without veering off into fantasy. As Kubrick said of the costumes: “The problem is to find something that looks different and that might reflect new developments in fabrics but that isn’t so far out as to be distracting … Certainly buttons will be gone. Even now, there are fabrics that stick shut by themselves.”

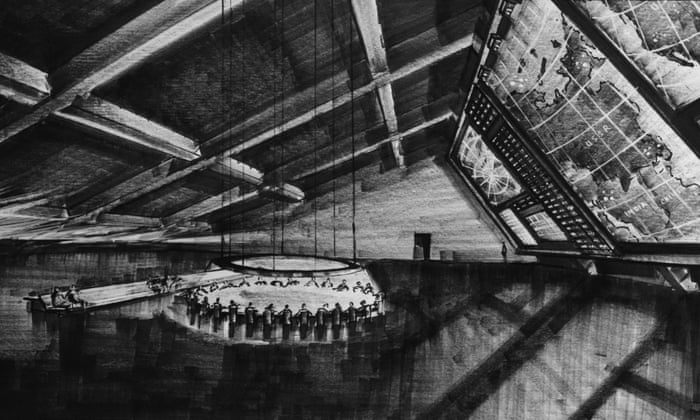

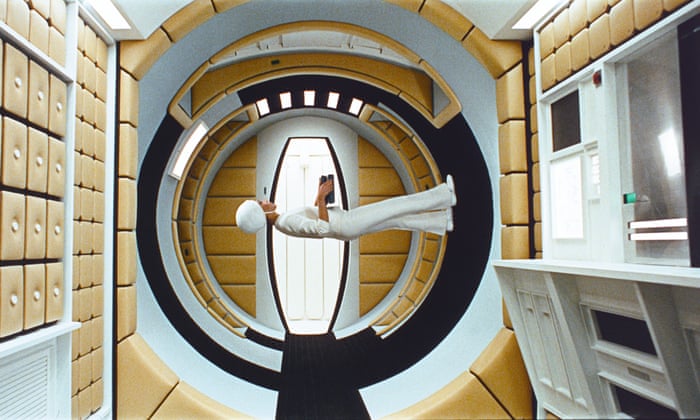

The centrifuge set, 2001

...and in the film.

The section of the exhibition devoted to 2001 – regarded by many as Kubrick’s crowning achievement – is a thrill, featuring original artwork, model spaceships, costumes and props galore. It includes a miniature mockup of the groundbreaking centrifuge set, a huge 12m-high hamster wheel that allowed scenes to be shot that appear to show the astronauts walking upside down (and which took British manufacturer Vickers-Armstrong six months and more than £580,000 to build).

Like every element of the epic film, it gave as accurate a representation as possible of what form the future of space travel might take, based on ideas developed by German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun for a giant spoked wheel that would have rotated around its axis to create artificial gravity for its occupants. Kubrick enhanced the sense of believability through familiarity, using a prodigious amount of product placement, from a Pan Am space shuttle to an Orbiter Hilton Hotel and an IBM tablet – preceding the iPad by 40 years.

The exhibition's A Clockwork Orange display

He had a keen sense of the latest contemporary design and technology, and often exploited its seductive power on film. “There is a sexiness to beautiful machines,” he said, “the smell of a Nikon, the feel of an Italian sports car or a beautiful tape recorder.” This fetishistic attitude to objects comes through in A Clockwork Orange, where the interiors are furnished with pieces that were commercially available at the time but unusual enough to give a sense of the near future. The protagonist’s bedroom features a scarlet Olivetti typewriter designed by Ettore Sottsass, alongside Herman Makkink’s Christ Unlimited sculptures and a futuristic transparent Transcriptor record player, designed by David Gammon.

Use of the steadicam in The Shining

But the polished results were rarely achieved without hiccups. The interiors of the milk bar, where the film opens, were originally going to be designed in collaboration with artist Allen Jones, whose provocative furniture made from submissive female mannequins had caught Kubrick’s eye. Jones even got as far as designing the waitresses’ uniforms for the film, conceiving skintight Lycra dresses with windows cut around the bottom. “I wanted a waitress costume that reflected the fact that, when bringing food, she is functional, and when departing she is decorative,” he said. The two maestros couldn’t agree on a fee, and so Jones’s work – like so many of the carefully prototyped designs elsewhere in the exhibition – was canned.

Using a Zeiss lens specially made for NASA to film by candlelight in Barry Lyndon

Perhaps the most striking thing that resurfaces throughout the show is how much of the immense trouble that Kubrick went to (and forced others to go through) was undertaken in order to avoid travelling. Despite having had a pilot’s license in his youth, he was scared of flying, so the vast majority of his films were shot in the UK. If he wouldn’t travel then the world would be brought to him, at astonishing lengths.

For his celebrated 1987 war film, Full Metal Jacket, Kubrick hired Royal College of Art architecture graduate Anton Furst to transform Beckton Gas Works in London into the Vietnamese city of Huế, using 200 living palm trees flown in from Spain and 100,000 plastic tropical plants from Hong Kong. The Parris Island training camp, meanwhile, was pieced together from a Territorial Army barracks in Bassingbourn, an abandoned airfield in Enfield and an army latrine at Shepperton Studios. Photographs show how Furst proposed to transform Beckton’s 1930s concrete relics into a vaguely southeast Asian-looking cityscape with strategic demolitions and additions.

For his final film, Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick attempted to recreate New York’s Greenwich Village from a collage of streets in London. He dispatched his brother-in-law’s son to assiduously photograph the entire length of Commercial Road, and created a surreal map of Manhattan, labelling each area with the London streets that could be used as stand-ins. It was a jigsaw approach he had used for his 1975 period drama, Barry Lyndon, when, after his team had searched England, Ireland and Germany to find the perfect stately home, they eventually pieced a mythical house together from 12 different sites. “He kept changing his mind, and I was racing around the Irish countryside trying to find locations,” recalled Ken Adam. “When he didn’t like the location, the whole thing would have to be shot again … It was a disaster.”

2001: A Space Odyessy

Kubrick’s uncompromising fastidiousness drove many of his collaborators mad, but most agreed that it was usually worth it for the quality of the final product. As Sydney Pollack put it in a 2012 documentary: “‘Perfectionist’ is usually a euphemism for ‘pain in the ass’. Stanley was the first real perfectionist.”

Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition is at the Design Museum, London, from 26 April to 15 September.

Saturday 27 April 2019

Friday 26 April 2019

Wednesday night's set lists at The Habit, York

Just My Imagination

The Air That I Breathe

Da Elderly: -

Romancing Tonight

Long May You Run

The Elderly Brothers: -

True Love Ways

Mailman, Bring Me No More Blues

When Will I Be Loved

Then I Kissed Her

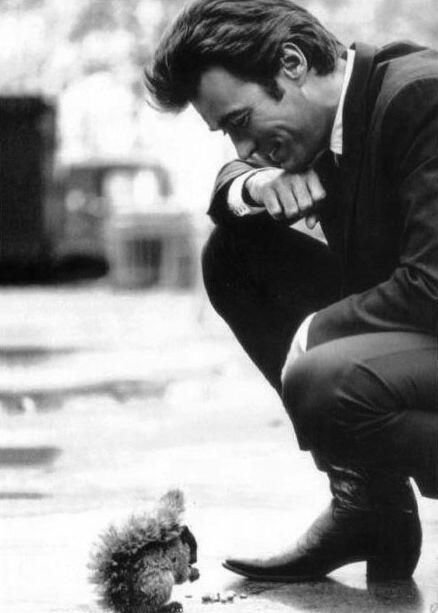

Walk Right Back

There was a sizable crowd in The Habit as the open mic night kicked off, but only four or five players initially. Fears were soon allayed as several players, including one or two lasses new to The Habit, arrived to entertain us. Occasional regular Leo (pictured) played a couple of Woody Guthrie songs on his resonator guitar and harmonica including a spirited Hard Travelin'. The Elderlys finished off the night, commencing with two Buddy Holly classics.

Thursday 25 April 2019

Tuesday 23 April 2019

Monday 22 April 2019

Sunday 21 April 2019

Saturday 20 April 2019

Visions of the Self: Rembrandt and Now at Gagosian, London

Visions of the Self: Rembrandt and Now review – the master upstages everyoneGagosian Grosvenor Hill, London

Theatrical, comical, tawdry and tenuous – self-portraits by the likes of Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman sit alongside Rembrandt’s great late painting, but he is simply the most present

Adrian Searle

A few works directly nod to Rembrandt. A Jeff Koons copy of another 1642-3 self-portrait, with a blue gazing ball, is kept, sensibly, out of sight of the real thing. Glenn Brown and Cindy Sherman ape an old-master look and dress. Brown’s red-nosed slithery version of an El Greco portrait, with frighteningly filmy eyes, and Sherman’s photograph, with a prosthetic mask, both attempt a kind of time-slip. Chicago painter Nathaniel Mary Quinn’s 2019 self-portrait “After Rembrandt” also uses Rembrandt’s fur jacket and chemise-like shirt. It is all a bit tenuous, really. And anyway, Rembrandt always wins. Not that it was ever a contest, because that would be pointless. It would also be spurious to look for a contemporary equivalent to Rembrandt, because there isn’t one. Somehow his self-portrait has a kind of presentness – in the here and now – much else lacks, which is a kind of marvellous riddle.

• At Gagosian Grosvenor Hill, London, 12 April to 18 May

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/apr/11/visions-of-the-self-rembrandt-and-now-review-the-master-upstages-everyone

Theatrical, comical, tawdry and tenuous – self-portraits by the likes of Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman sit alongside Rembrandt’s great late painting, but he is simply the most present

Adrian Searle

The Guardian

11 Apr 2019

Rembrandt’s late self-portrait sits in its glazed frame in the centre of a large grey wall at Gagosian’s central London Grosvenor Hill gallery. Usually it hangs in Kenwood House on the northern edge of Hampstead Heath, sharing the galleries with Gainsborough’s wonderful portrait of Lady Howe, a Vermeer, and assorted 18th- and 19th-century paintings of varying qualities. But no matter. Here it is again, on a grey wall all by itself, with no bits of furniture getting in the way, on loan from English Heritage. But Rembrandt is far from alone here. His circa 1665 Self-Portrait with Two Circles (not the painting’s original title, if it ever had one) shares a whole gallery with much more recent artists, many of whom are part of Gagosian’s stable. For now, I have my back to them.

I have been looking at this painting for more than 40 years. The light on the face and cap, the two partial circles on the wall behind him (perhaps the outline of an otherwise unpainted Mappa Mundi), and what Picasso called “that elephant eye of his”. Rembrandt is the elephant in the room. Even out of sight, around the corner or in a different part of the gallery, you know he’s there, when you’re looking at a Gerhard Richter, a Richard Prince, or a funny painting by Dora Maar. You want Picasso? Here’s his last self-portrait, the skull grinning through in a 1972 sketch. The charcoal scribble across the mouth is almost a duplicate of the scratching on Rembrandt’s collar, a singular moment in the portrait where Rembrandt picked up his painting knife or used the back end of his brush to scratch through the wet paint with a sort of impetuous haste.

Rembrandt shares a room with Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Robert Mapplethorpe and a small Andy Warhol. Another, later Warhol, a vast self-portrait of the artist in a fright wig, glowers across at Rembrandt from the adjacent space. Bacon and Freud both look forced. Both Andy, in that wig with its electrified nylon hair, and Rembrandt, in his smock and cap and furs, have dressed for the occasion. Self-portraiture is always a performance, even when it affects not to be. Perhaps most of all when it tries to be as natural and as candid as it possibly can. This entire show is a piece of theatre. With his tawdry, threadbare magnificence Rembrandt upstages everyone, and there’s quite a crowd. You want Howard Hodgkin (why would anybody)? – here’s a dabbled over confection, consigned to the entrance lobby. You want Damien Hirst? Check – a photo of the young artist gleeful, next to a severed head. There’s plenty of mortality here: Robert Mapplethorpe, sick with Aids, with his skull-topped cane; Georg Baselitz’s Grosse Nacht, a compellingly nasty 1962-3 figure, hand on cock, whose limbs appear diseased. This is from the best period of Baselitz’s work. You want Christopher Wool’s giant Rorschach-like head-blob thing? What for?

Untitled #220, 1990, by Cindy ShermanRembrandt’s late self-portrait sits in its glazed frame in the centre of a large grey wall at Gagosian’s central London Grosvenor Hill gallery. Usually it hangs in Kenwood House on the northern edge of Hampstead Heath, sharing the galleries with Gainsborough’s wonderful portrait of Lady Howe, a Vermeer, and assorted 18th- and 19th-century paintings of varying qualities. But no matter. Here it is again, on a grey wall all by itself, with no bits of furniture getting in the way, on loan from English Heritage. But Rembrandt is far from alone here. His circa 1665 Self-Portrait with Two Circles (not the painting’s original title, if it ever had one) shares a whole gallery with much more recent artists, many of whom are part of Gagosian’s stable. For now, I have my back to them.

I have been looking at this painting for more than 40 years. The light on the face and cap, the two partial circles on the wall behind him (perhaps the outline of an otherwise unpainted Mappa Mundi), and what Picasso called “that elephant eye of his”. Rembrandt is the elephant in the room. Even out of sight, around the corner or in a different part of the gallery, you know he’s there, when you’re looking at a Gerhard Richter, a Richard Prince, or a funny painting by Dora Maar. You want Picasso? Here’s his last self-portrait, the skull grinning through in a 1972 sketch. The charcoal scribble across the mouth is almost a duplicate of the scratching on Rembrandt’s collar, a singular moment in the portrait where Rembrandt picked up his painting knife or used the back end of his brush to scratch through the wet paint with a sort of impetuous haste.

Rembrandt shares a room with Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Robert Mapplethorpe and a small Andy Warhol. Another, later Warhol, a vast self-portrait of the artist in a fright wig, glowers across at Rembrandt from the adjacent space. Bacon and Freud both look forced. Both Andy, in that wig with its electrified nylon hair, and Rembrandt, in his smock and cap and furs, have dressed for the occasion. Self-portraiture is always a performance, even when it affects not to be. Perhaps most of all when it tries to be as natural and as candid as it possibly can. This entire show is a piece of theatre. With his tawdry, threadbare magnificence Rembrandt upstages everyone, and there’s quite a crowd. You want Howard Hodgkin (why would anybody)? – here’s a dabbled over confection, consigned to the entrance lobby. You want Damien Hirst? Check – a photo of the young artist gleeful, next to a severed head. There’s plenty of mortality here: Robert Mapplethorpe, sick with Aids, with his skull-topped cane; Georg Baselitz’s Grosse Nacht, a compellingly nasty 1962-3 figure, hand on cock, whose limbs appear diseased. This is from the best period of Baselitz’s work. You want Christopher Wool’s giant Rorschach-like head-blob thing? What for?

A few works directly nod to Rembrandt. A Jeff Koons copy of another 1642-3 self-portrait, with a blue gazing ball, is kept, sensibly, out of sight of the real thing. Glenn Brown and Cindy Sherman ape an old-master look and dress. Brown’s red-nosed slithery version of an El Greco portrait, with frighteningly filmy eyes, and Sherman’s photograph, with a prosthetic mask, both attempt a kind of time-slip. Chicago painter Nathaniel Mary Quinn’s 2019 self-portrait “After Rembrandt” also uses Rembrandt’s fur jacket and chemise-like shirt. It is all a bit tenuous, really. And anyway, Rembrandt always wins. Not that it was ever a contest, because that would be pointless. It would also be spurious to look for a contemporary equivalent to Rembrandt, because there isn’t one. Somehow his self-portrait has a kind of presentness – in the here and now – much else lacks, which is a kind of marvellous riddle.

• At Gagosian Grosvenor Hill, London, 12 April to 18 May

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)