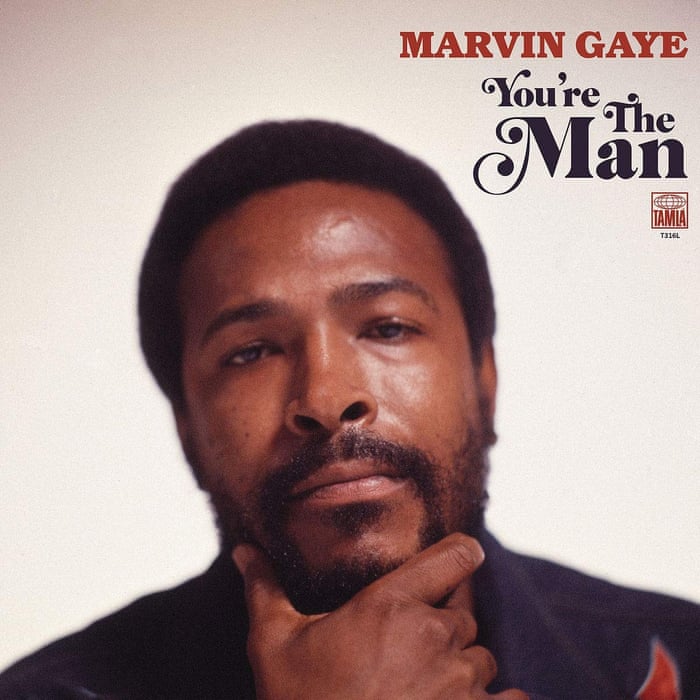

Marvin Gaye: You're the Man review – 'lost album' sits at crossroads of soul

Remixed and repackaged collection finds a troubled artist caught between the socially conscious What’s Going On and the Motown machineAlexis Petridis

The Guardian

28 March 2019

In early 1972, Marvin Gaye should have been on top of the world. The previous year, he had wrested control of his career from Motown’s draconian hit-making system, winning a bitter battle to get What’s Going On released as a single: the song Motown boss Berry Gordy claimed was “the worst piece of crap I ever heard” spent five weeks at No 1 in the US R&B chart. The album of the same name had sold a million copies, been nominated for two Grammys and redefined perceptions of Motown both externally and internally. A label previously dominated by singles had released a critically acclaimed, wildly successful concept album. An emboldened Stevie Wonder was now making it clear that he too was sick of the label’s insistence on total control. In the wake of What’s Going On, Gaye had been named trendsetter of the year by Billboard magazine, and re-signed with Motown in what was, at the time, the most lucrative deal ever struck by a black artist.

But, as was invariably the case in Gaye’s complex and troubled life, all was not as it seemed. Just as the 1968 success of I Heard It Through the Grapevine had left him oddly resentful and insecure – he hadn’t written the song, so he “felt like a puppet” – and he found the acclaim afforded What’s Going On “heavy”. As he told biographer David Ritz: “When you’re at the top there’s nowhere to go but down.” And his battle with Motown wasn’t over. When Gordy heard Gaye’s next single, You’re the Man – a bleak, distrustful assessment of the 1972 US presidential campaign, intended as the title track of a forthcoming album but lacking the kind of luscious melodies that had flowed through What’s Going On – he either panicked or coolly enacted revenge for Gaye’s earlier revolt: Motown pulled promotion and pressured radio stations to drop it from their playlists, ensuring it flopped.

This 17-track collection named after that song tries to make sense of what happened next. Grandly billed as a great lost album, it’s really a compilation of cancelled singles and studio outtakes, some of them polished up for release by Amy Winehouse producer Salaam Remi. They capture the sound of an artist who clearly doesn’t know what to do. At some sessions, Gaye forged ahead with the idea of another album in the socially conscious vein of What’s Going On. He reworked You’re the Man in the hazy, shimmering style of that album, and recorded Woman of the World – an ostensibly breezy ode to feminism that on closer inspection seems to be grousing that women’s lib is interfering with the more important business of Marvin Gaye getting his leg over. The fantastic The World Is Rated X similarly suggests that his attitude had become more cynical than that of the saintly figure pleading we Save the Children a year previously.

At other sessions, however, Gaye behaved as though he thought Gordy might have had a point, meekly returning to Motown business as usual. He taped a series of songs with Willie Hutch, subsequently best known for his blaxploitation soundtracks to The Mack and Foxy Brown, but then a Motown staff writer. To say what they recorded is standard-issue lightweight early 70s Motown pop would be underselling it slightly – I’m Gonna Give You Respect is a fabulous, effervescent song, and Gaye gives it his all – but it’s a world away from Inner City Blues or What’s Happening Brother. But another song by staffers, Gloria Jones and Pamela Sawyer’s Piece of Clay, is inspired, its gospel sound spattered with a howling psychedelic guitar: soul’s past tied together with its present.

Elsewhere, You’re the Man unearths a cache of great unreleased ballads from 1969, of which Symphony is both the best song and a reminder of the perils of letting a hot producer loose on old material. Apparently working on the demented principle that Gaye’s work would be improved if it sounded as if it was recorded last week, Salaam Remi has faffed with the drums to give them a contemporary feel. If his approach is marginally more subtle than the late-80s practice of just whacking a drum machine on top of a vintage track, it’s clearly going to date in a way the original recording – released in 2009 on the deluxe edition of Gaye’s 1973 album Let’s Get It On – has not.

Gaye found his route out of confusion by unlikely means, recording a Christmas single that Motown declined to release. Understandably so: I Want to Come Home for Christmas was a desolate slab of misery written from the perspective of a prisoner of war, while Christmas in the City was a funereal-paced synthesiser instrumental. But the latter prefigured Gaye’s hit soundtrack to Trouble Man, just as Woman of the World’s suggestion that politics mattered less to Gaye than sex prefigured Let’s Get It On. The music he abandoned in order to release those albums is a fascinating jumble of ideas, some of them fantastic. Too confused to be a great lost album, or indeed a coherent collection, as a snapshot of both its creator and soul music in turmoil, it’s perfect.

28 March 2019

In early 1972, Marvin Gaye should have been on top of the world. The previous year, he had wrested control of his career from Motown’s draconian hit-making system, winning a bitter battle to get What’s Going On released as a single: the song Motown boss Berry Gordy claimed was “the worst piece of crap I ever heard” spent five weeks at No 1 in the US R&B chart. The album of the same name had sold a million copies, been nominated for two Grammys and redefined perceptions of Motown both externally and internally. A label previously dominated by singles had released a critically acclaimed, wildly successful concept album. An emboldened Stevie Wonder was now making it clear that he too was sick of the label’s insistence on total control. In the wake of What’s Going On, Gaye had been named trendsetter of the year by Billboard magazine, and re-signed with Motown in what was, at the time, the most lucrative deal ever struck by a black artist.

But, as was invariably the case in Gaye’s complex and troubled life, all was not as it seemed. Just as the 1968 success of I Heard It Through the Grapevine had left him oddly resentful and insecure – he hadn’t written the song, so he “felt like a puppet” – and he found the acclaim afforded What’s Going On “heavy”. As he told biographer David Ritz: “When you’re at the top there’s nowhere to go but down.” And his battle with Motown wasn’t over. When Gordy heard Gaye’s next single, You’re the Man – a bleak, distrustful assessment of the 1972 US presidential campaign, intended as the title track of a forthcoming album but lacking the kind of luscious melodies that had flowed through What’s Going On – he either panicked or coolly enacted revenge for Gaye’s earlier revolt: Motown pulled promotion and pressured radio stations to drop it from their playlists, ensuring it flopped.

This 17-track collection named after that song tries to make sense of what happened next. Grandly billed as a great lost album, it’s really a compilation of cancelled singles and studio outtakes, some of them polished up for release by Amy Winehouse producer Salaam Remi. They capture the sound of an artist who clearly doesn’t know what to do. At some sessions, Gaye forged ahead with the idea of another album in the socially conscious vein of What’s Going On. He reworked You’re the Man in the hazy, shimmering style of that album, and recorded Woman of the World – an ostensibly breezy ode to feminism that on closer inspection seems to be grousing that women’s lib is interfering with the more important business of Marvin Gaye getting his leg over. The fantastic The World Is Rated X similarly suggests that his attitude had become more cynical than that of the saintly figure pleading we Save the Children a year previously.

At other sessions, however, Gaye behaved as though he thought Gordy might have had a point, meekly returning to Motown business as usual. He taped a series of songs with Willie Hutch, subsequently best known for his blaxploitation soundtracks to The Mack and Foxy Brown, but then a Motown staff writer. To say what they recorded is standard-issue lightweight early 70s Motown pop would be underselling it slightly – I’m Gonna Give You Respect is a fabulous, effervescent song, and Gaye gives it his all – but it’s a world away from Inner City Blues or What’s Happening Brother. But another song by staffers, Gloria Jones and Pamela Sawyer’s Piece of Clay, is inspired, its gospel sound spattered with a howling psychedelic guitar: soul’s past tied together with its present.

Elsewhere, You’re the Man unearths a cache of great unreleased ballads from 1969, of which Symphony is both the best song and a reminder of the perils of letting a hot producer loose on old material. Apparently working on the demented principle that Gaye’s work would be improved if it sounded as if it was recorded last week, Salaam Remi has faffed with the drums to give them a contemporary feel. If his approach is marginally more subtle than the late-80s practice of just whacking a drum machine on top of a vintage track, it’s clearly going to date in a way the original recording – released in 2009 on the deluxe edition of Gaye’s 1973 album Let’s Get It On – has not.

Gaye found his route out of confusion by unlikely means, recording a Christmas single that Motown declined to release. Understandably so: I Want to Come Home for Christmas was a desolate slab of misery written from the perspective of a prisoner of war, while Christmas in the City was a funereal-paced synthesiser instrumental. But the latter prefigured Gaye’s hit soundtrack to Trouble Man, just as Woman of the World’s suggestion that politics mattered less to Gaye than sex prefigured Let’s Get It On. The music he abandoned in order to release those albums is a fascinating jumble of ideas, some of them fantastic. Too confused to be a great lost album, or indeed a coherent collection, as a snapshot of both its creator and soul music in turmoil, it’s perfect.

No comments:

Post a Comment