Van Gogh and Britain review – on the town with Vincent

Tate Britain, London

The artist’s heady London years are the backdrop to a show that struggles to locate a British influence on this singularly self-propelled genius

Laura Cumming

Tate Britain, London

The artist’s heady London years are the backdrop to a show that struggles to locate a British influence on this singularly self-propelled genius

Laura Cumming

The Observer

31 March 2019

Van Gogh loved Dickens. He wore a top hat on his daily walk to work from Brixton to Covent Garden. He rowed on the Thames, studied Turner and Constable in the National Gallery, even took the new underground railways. That he lived in London, on and off, between the spring of 1873 and the winter of 1876 still seems as surprising as Géricault painting the Epsom Derby and Canaletto working for nine years in Soho. But there is a crucial difference: Van Gogh was not yet a painter.

He was only 20 when a posting came up at the London branch of Goupil, the French art dealer for whom he worked in The Hague. A thumbnail sketch of Westminster Bridge on the company’s headed notepaper is one of only three drawings that survive from Van Gogh’s time in England. Fired from Goupil, and from his Brixton boarding house, where he fell in love with the landlady’s daughter (or possibly the widow herself, it is sometimes said), he briefly taught at a school in Ramsgate, before a stint as a Methodist lay preacher in Richmond. Not until the summer of 1880, when Van Gogh was 27, did he decide to become an artist.

But wasn’t Vincent born, and not made – his incomparable genius entirely sui generis? The standard piety is that art always comes from art, that no painter just appears out of nowhere. That is certainly the line the curators toe in this show, as they surely must, for the central premise of Van Gogh in Britain is that he was thoroughly steeped in British art. Other shows have argued the case for French Impressionism, Japanese prints, the paintings of Rembrandt or Jean-Francois Millet with considerably more success, for the simple reason that these influences are plain to see. Britain is a much bigger problem.

Prisoners Exercising, 1890

31 March 2019

Van Gogh loved Dickens. He wore a top hat on his daily walk to work from Brixton to Covent Garden. He rowed on the Thames, studied Turner and Constable in the National Gallery, even took the new underground railways. That he lived in London, on and off, between the spring of 1873 and the winter of 1876 still seems as surprising as Géricault painting the Epsom Derby and Canaletto working for nine years in Soho. But there is a crucial difference: Van Gogh was not yet a painter.

He was only 20 when a posting came up at the London branch of Goupil, the French art dealer for whom he worked in The Hague. A thumbnail sketch of Westminster Bridge on the company’s headed notepaper is one of only three drawings that survive from Van Gogh’s time in England. Fired from Goupil, and from his Brixton boarding house, where he fell in love with the landlady’s daughter (or possibly the widow herself, it is sometimes said), he briefly taught at a school in Ramsgate, before a stint as a Methodist lay preacher in Richmond. Not until the summer of 1880, when Van Gogh was 27, did he decide to become an artist.

But wasn’t Vincent born, and not made – his incomparable genius entirely sui generis? The standard piety is that art always comes from art, that no painter just appears out of nowhere. That is certainly the line the curators toe in this show, as they surely must, for the central premise of Van Gogh in Britain is that he was thoroughly steeped in British art. Other shows have argued the case for French Impressionism, Japanese prints, the paintings of Rembrandt or Jean-Francois Millet with considerably more success, for the simple reason that these influences are plain to see. Britain is a much bigger problem.

Prisoners Exercising, 1890

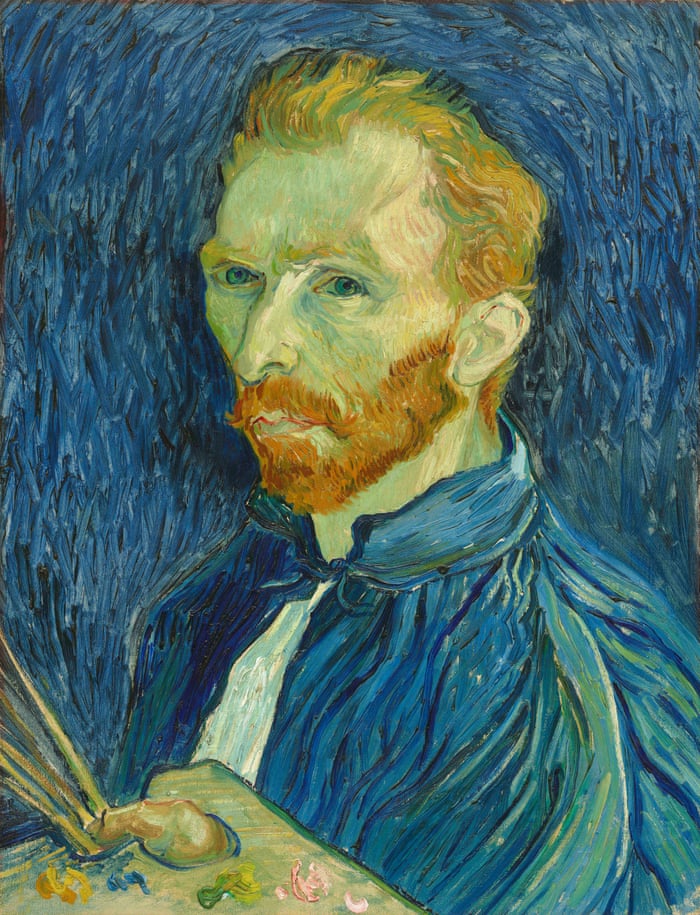

There are more than 50 works by Van Gogh in this show, including a trio of magnificent self-portraits, the great Starry Night Over the Rhône from the Musée d’Orsay, the National Gallery’s Sunflowers, and several astonishing masterpieces coaxed out of private collections. It is vital to know they are there, glowing at distant intervals somewhere in the glum labyrinth of prints, documents and subfusc mediocrities, otherwise you might become discouraged.

It is true that the show also contains John Everett Millais’s powerfully dreich Chill October, which Van Gogh loved, and may have remembered when painting the dying light in his own Autumn Landscape at Dusk a whole decade later. And here is a Whistler Nocturne, though it is a considerable stretch to suggest that it had any effect whatsoever on Starry Night, with its golden emblems of hope ablaze in the midnight skies over the Rhône. Van Gogh’s supreme originality is all there in those stars and whorls and flakes of brilliant light. And Whistler was, in any case, American.

That Van Gogh learned from Gustave Doré (French) is not in doubt. Doré’s deathless etchings show London as a gaslit netherworld of poverty, smog and casual injustice, workers jammed in claustrophobic back-to-backs, addicts in opium dens, deprivation in doss houses. Van Gogh bought a complete set and even copied one print of prisoners forced to walk a cramped circle round and round Newgate yard. But his version is a painting, astoundingly bright, as if heaven were shining down upon these poor, benighted figures. It is the strangest paradox, a beautiful painting of the bleakest subject: a redemptive vision of hell.

Prisoners Exercising comes from the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. It is described by the curators as Van Gogh’s “only painting of London”, a curious claim, since he never saw the scene and made the work in Arles towards the end of his life. They are on firmer ground with those dark and knotted drawings of peasants from his early days back home in his father’s gloomy house, which do seem visually connected to the many English prints he saw in London in The Graphic magazine.

Woman Sitting on a Basket with Head in Hands, 1883

And you can just about believe the argument that Van Gogh’s portrait of his empty chair, stalwart yet humble, may have been inspired by Luke Fildes’s 1870 engraving of Dickens’s vacant study after the writer’s death. But that doesn’t begin to explain the marvellous expressiveness of Van Gogh’s portrait of his lonely possession, or the protectiveness millions of viewers feel towards that chair.

Van Gogh’s writings show admiration for lesser artists all through his life; his humility is deeply affecting. But it is no excuse for displaying so many of their works. And then the show goes the other way, with slews of British paintings influenced by Van Gogh, from Matthew Smith to Harold Gilman, Spencer Gore and Jacob Epstein. A whole gallery is devoted to their dahlias, chrysanthemums and lilies; any old flower, so long as it’s yellow and looks like a feeble tribute to The Sunflowers.

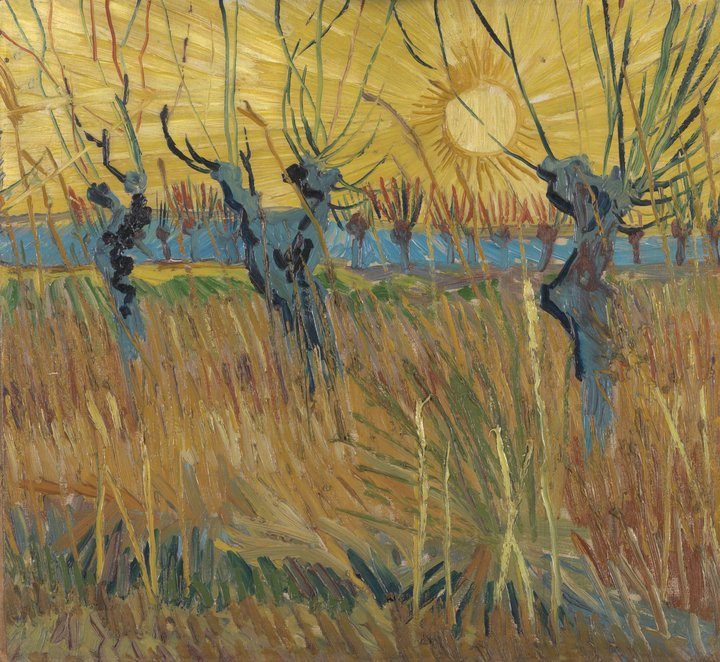

Shoes, 1886

A Scotsman named Alexander Reid bought a painting directly from Van Gogh in 1887 – or at least he paid for the fruit depicted. A basket of apples surges like a life raft on an ocean of brushstrokes, flowing in waves and squalls up the canvas. Speed through the flower gallery – which feels like a form of crowd control, designed to deal with recurrent bottlenecks – and you will also encounter a spectacular yew tree, standing silver against a flaring yellow sky. And then a Wheatfield from the high summer of 1888, where the dabs and curlicues flow in wildly different directions and the hum of heat and light is so dynamic the picture is practically bursting.

The sheer joy of it all is what strikes every time: every brushload laid upon the surface an act of exultation, every colour a kind of gratitude. Shivering harvest fields, delicate branches spreading like Hiroshige’s cherry blossoms, the trees outside the hospital at Saint-Rémy rippling to the cobalt skies like the flames of a summer fire, the asylum itself a stately golden palace. Even in a late self-portrait from the last summer of his life, when Van Gogh had been ill and was staying there, the painting is all exhilaration. The face is almost entirely green – “the green of a summer sky”, he called it – and the hair blazes up gold as a wind-flurried wheat field. You cannot look at it without being intensely aware of every stroke, the way the hand held the brush, pressing its freight of brilliant colour into the springy surface of the canvas over and again, this way and that – Van Gogh’s singular idiom, his spirit, at work.

Pollarded Willows, 1888

It is no overstatement to speak of the aura of his paintings. And no disrespect to Whistler, Doré or any of the British artists in this show, to say that their contribution to Van Gogh’s brief but soaring flight is quite obviously negligible. It is still amazing to think how high and far Van Gogh flew, before killing himself at the age of 37. From the early chalk drawings in this show, tentative and ungainly, to the whirling skies and crackling trees and radiant stars, to the dizzying morphology of brush-marks that channel the sensational flow of his mind, eye and passion, it is barely a single, hurtling decade.

• Van Gogh and Britain is at Tate Britain, London, until 11 August

No comments:

Post a Comment