At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

Streets Of London

My Home Town

Da Elderly: -

Out On The Weekend

Heart Of Gold

The Elderly Brothers: -

Crying In The Rain

The Sound Of Silence

When Will I Be Loved

Then I Kissed Her

Out Of Time

Medley: High Heel Sneakers/It's All Over Now

After holidays and following Neil Young's tour of Europe, The Elderly Brothers made a welcome return to The Habit on what turned out to be a busy night. With plenty of players and, eventually a bar full of punters, there was the usual eclectic mix of musical styles on show. Our host was interrupted during his closing song with a rousing chorus of "Happy Birthday To You" as the clock struck 12 and celebrations continued until chucking-out time.

Thursday 30 June 2016

Wednesday 29 June 2016

Happy 90th birthday to Mel Brooks...

A day late we know, but we hope he doesn't mind...

Celebrating Mel Brooks On His 90th Birthday: A Classic Routine

28 June 2016

Everyone thought he was crazy when Mel Brooks told them he was going to make a movie about a Broadway musical called "Springtime For Hitler." But "The Producers" now considered a satirical masterpiece, won the fledgling filmmaker a 1968 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and turned his career around.

While he's best known today for hilarious films like "Young Frankenstein," "High Anxiety" and "Blazing Saddles," and for his later in life Broadway success with THE PRODUCERS and YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, during the 1950s Brooks was primarily known as a sketch comedy writer. His Broadway debut came penning scenes for the revue Leonard Sillman'S NEW FACES OF 1952, which featured his bit where a small-time crook, played by Paul Lynde, was upset because his son (Ronny Graham) wanted to be a musician instead of following in his footsteps.

He then turned to television, joining Carl Reiner, Neil Simon and Larry Gelbart on the writing staff of Sid Caesar's "Caesar's Hour," before heading back to Broadway as co-bookwriter of SHINBONE ALLEY, a musical based on Don Marquis' stories of "archie and mehitabel," about a poetry-writing cockroach and his alley cat friend.

His book for the 1962 musical ALL-AMERICAN (score by Charles Strouse and Lee Adams) had Ray Bolger playing a European college professor who takes a position at a football crazy American university and uses mathematical equations to turn their sorry football team into winners.

During this time, Brooks' outrageous personality and energy made him a popular television guest, especially when he and Reiner teamed up for routines where Brooks was interviewed as a 2,000 year old man.

While he's best known today for hilarious films like "Young Frankenstein," "High Anxiety" and "Blazing Saddles," and for his later in life Broadway success with THE PRODUCERS and YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, during the 1950s Brooks was primarily known as a sketch comedy writer. His Broadway debut came penning scenes for the revue Leonard Sillman'S NEW FACES OF 1952, which featured his bit where a small-time crook, played by Paul Lynde, was upset because his son (Ronny Graham) wanted to be a musician instead of following in his footsteps.

He then turned to television, joining Carl Reiner, Neil Simon and Larry Gelbart on the writing staff of Sid Caesar's "Caesar's Hour," before heading back to Broadway as co-bookwriter of SHINBONE ALLEY, a musical based on Don Marquis' stories of "archie and mehitabel," about a poetry-writing cockroach and his alley cat friend.

His book for the 1962 musical ALL-AMERICAN (score by Charles Strouse and Lee Adams) had Ray Bolger playing a European college professor who takes a position at a football crazy American university and uses mathematical equations to turn their sorry football team into winners.

During this time, Brooks' outrageous personality and energy made him a popular television guest, especially when he and Reiner teamed up for routines where Brooks was interviewed as a 2,000 year old man.

In this 1967 clip from the Colgate Comedy Hour, Brooks and Reiner are introduced by Dick Shawn for a set that includes an explanation of how applause was invented.

Happy 90th birthday to funnyman Mel Brooks

28 June 2016

A tip of the hat to funnyman Mel Brooks, who turns 90 today! The director of "Blazing Saddles," "Young Frankenstein" and "The Producers" is one of the few people alive who've earned an EGOT: an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony.

He was born Melvin Kaminsky on June 28, 1926 in Brooklyn. He began his career as a comic and a writer for the early TV variety show "Your Show of Shows." Along with Buck Henry, he created the hilarious '60s spy spoof series "Get Smart."

He went on to direct some of the best-known comedy films of all time, including "The Producers," "Blazing Saddles," "Young Frankenstein," "Silent Movie," "High Anxiety," and "Spaceballs." He won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for "The Producers" and received nominations for the screenplay for "Young Frankenstein" (which he co-wrote with Gene Wilder) and for the song "Blazing Saddles" from the film of the same name.

The Broadway adaptation of "The Producers" starring Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick ran from 2001 to 2007 and won a record-breaking 12 Tony Awards.

Brooks was married to Oscar-winning actress Anne Bancroft from 1964 until her death in 2005. Their son Max Brooks wrote "The Zombie Survival Guide" and "World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War," which became the hit Brad Pitt film.

Here's some of the ways you can celebrate Mel Brooks's birthday today:

Join the Mel Brooks Blogathon

Follow Mel on Twitter. (He describes himself as "Writer, Director, Actor, Producer and failed Dairy Farmer.")

Read "The 10 Funniest Lines From His AFI Tribute"

Watch the career-spanning documentary "Mel Brooks: Make a Noise" on Netflix or PBS

Listen to Mel Brooks recreate his classic 2000-Year-Old Man character as he talks about what Times Square was like back then

Buy "The Mel Brooks Collection" on Amazonhttp://www.examiner.com/article/happy-90th-birthday-to-funnyman-mel-brooks

Tuesday 28 June 2016

Quentin Tarantino talks music and films

For the first time since Hitchcock, moviegoers have embraced a film director whose name denotes a genre in itself.

Transcending his reputation as a maker of violent movies, Quentin Tarantino is also recognised by his fans and admirers as an exceptional soundtrack producer. True Romance, Natural Born Killers, Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown, Kill Bill... Tarantino selected all the tracks himself. In the first of two programmes, the enfant terrible of American Cinema reveals his musical obsessions and his influences, and talks us through the contents of his virtual jukebox.

Music is a critical element in many movies, but never more so than in Tarantino's - he plunders his own backstory, remembering the tracks of his youth, as well as often making references to - and featuring music from - cult movies and television.

This intriguing documentary (coming to you from the red leatherette banquettes of Quentin's favourite virtual diner in LA) not only forage in the annals of great popular music, they provide a unique insight into the way music can infuse a film, and the way a film can bring music back from the dusty vaults.

Also featuring Mary Wilson of the Supremes, Vicki Wickham (manager of Dusty Springfield), film producer Laurence Bender, music & movie critic Paul Gambaccini, film editor Sally Menke and music supervisors Mary Ramos and Karyn Rachtman.

Presented by conductor/composer & film-music historian Robert Ziegler.

Sunday 26 June 2016

Matthew and Michael Dickman interview 2016

‘The only way I could really talk about his suicide was in a poem’

When their half-brother took a fatal overdose, twins Matthew and Michael Dickman wrote a series of poems in his honour. Now, the collection is breaking taboos about suicide and inviting comparisons with America’s great poetsAlex Clark

Sunday 19 June 2016

If you go to interview twin poets about the death of their elder brother, and the work they have made jointly in response to it, your natural expectation is that the atmosphere will be serious, even sombre. And, indeed, my conversation with American writers Matthew and Michael Dickman, whose book revolves around the suicide, a decade ago, of their half-brother Darin Hull, frequently enters inevitably painful emotional territory, and the extent to which art is ever able to chart a course through it. But the morning that we spend together is punctuated with gusts of hilarity, irreverence, playfulness and informality, the alternating rainstorms and sunshine that flood the Bloomsbury streets outside an almost too neat pathetic fallacy.

The laughs begin straight away, as we’re settling down, and Michael – the older of the 40-year-old twins by two minutes, and a shade more reserved than Matthew – is pouring us coffee. One brother – I forget which now, because they both do it – calls the other “Chancho”. What’s behind that nickname, I ask. Ah, they reply; yes, they’d better explain. “Since high school we’ve called each other pig,” says Michael, “and then versions of it in different languages, like cochon or chancho, or the diminutive in Spanish, chanchito.” “Also, piggy, or Mr Pig,” adds Matthew. “Or Piggums,” rounds off Michael. They also have pig tattoos on their arms.

It emerges that “one of the only books we seem to have gotten through in high school” was William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, and Piggy was the character with whom they identified. “Piggy is heavier set, with glasses, and he gets picked on,” explains Matthew, “and my brother and I went through a period of getting really picked on a lot in school.” But even more touchingly, Michael recalls the moment at the end of the book when the schoolboy Ralph “refers to the now deceased Piggy as his one true good friend. And that was always true of Matthew.”

I’ve already apologised for talking about twin stuff the minute I arrived – how to tell them apart, etc. They’re used to it, they say, graciously. But now I point out that their affinity with Lord of the Flies is interesting: after all, before it descends into savagery, the novel delivers a version of the fantasy that all children have, of a sudden and decisive release from adult control, and the emergence of a world in which they can make their own rules. It is a mirror of the way people often view twins – bound together in a space of their own, and at some level immune to the demands of others. Is that a cliche?

“It certainly happened with us,” replies Michael, remembering the private language they had as toddlers (a paediatrician told their mother to put a stop to it). “There was never a question that we would have someone to play with, or who we would sit with in the cafeteria. Not that we didn’t have those terrible lonely moments for children growing up – but we at least had each other.”

Did they feel like that within their own family, too?

“Still!” laughs Matthew. “If all the family members get together for Christmas dinner or Thanksgiving, Michael and I – every time – will sequester ourselves in the kitchen, saying ‘Oh, we’ll cook for everybody because we love cooking’. We do love cooking, but just to get away from everything and have protection. And as the evening goes on, and people are in the living room drinking wine and suffering, once in a while they’ll come in to the kitchen and say, ‘Do you guys need any help?’ in this desperate way, you know, ‘Will you please save me?"

Michael: “Very little, actually.”

Matthew: “It’s way more self-indulgent – it’s more like we just want to hang out.”

Michael: “And you know, we have this sense of humour that we’ve been working on since childhood, which isn’t always shared with everyone at a family get-together.”

Hiding in the kitchen notwithstanding, their family ties are evident in Brother, a selection of poems from their previous books, collected here for the first time. The book – a “tête-bêche”, or “head-to-tail” edition, in which each poet’s work occupies a part of the book, which is printed upside down in relation to the other’s – is dedicated to their elder sister, Dana. Eleven years older than Michael and Matthew, she and Darin, who was born in 1968, were the children of Allen Hull, who some years later conceived the twins during a brief relationship with their mother, Wendy Dickman. He lived nearby, in Portland, Oregon, but never as part of their family; Wendy went on to have another daughter, Elizabeth, with a new partner.

As their half-brother, the twins tell me, Darin exerted an immense influence on them. Describing the first time he wrote about Darin’s death from an overdose, in the poem “Trouble”, Matthew explains: “The only way I could really talk about his suicide was by including him in this poem that is basically a long list of famous people who killed themselves. Because Darin was such a famous person in my mind and my heart.”

Trouble, which appeared in Matthew’s debut collection, All-American Poem(2008), also appears in Brother, and in the middle of a chronicle of the deaths of Marilyn Monroe, Ernest Hemingway, Sarah Kane and John Berryman come these lines:

“My brother opened / thirteen fentanyl patches and stuck them on his body / until it wasn’t his body any more.”

Elsewhere, in the poem Coffee, part of a sequence entitled Notes Passed to My Brother on the Occasion of His Funeral, Matthew writes:

“Once, I had a brother / who used to sit and drink his coffee black, smoke / his cigarettes and be quiet for a moment / before his brain turned its armadas against him”.

I ask them why Darin felt so “famous” to them. “We were raised without a father, and so I think there’s part of us that, through our older brother, got some of that energy,” says Matthew. “He would make you feel very special in his company. He was someone who had this really big, empathic heart – for years, he worked with troubled youth in different programmes. So he was, in our minds, always beloved, and complicated.”

“And he and Dana were just so cool,” chips in Michael. “Listening to the Cure, and smoking clove cigarettes.” Darin, who shared the twins’ love of skateboarding, took them from the “nice, family” supply stores to somewhere called Rebel Skates – edgy, sketchy, downtown. He and Dana added British bands such as Cocteau Twins and Joy Division to their playlists of punk and west coast rap.

Darin’s death came after problems with drugs and alcohol, but Brother is not coy about the manner of his death. “You know that our older brother killed himself: it’s not hidden,” Matthew says. “And it’s not really even hidden in our poems. And that’s something that I’m excited about with this book, because I think that the subject of suicide, at least in the States, is still one that there’s a lot of shame around, a lot of complicated feelings around; people keep it quiet.”

The poems themselves didn’t come for a long time. Neither of them, as Matthew puts it, “are poets who believe you experience something and you immediately need to write about it, or it needs to be a poem at all”.

While Matthew’s poetry has an expansive, free-associative, narrative style, Michael’s tends towards the spartan and oblique, appearing to portray an interior world under immense pressure, and it came as a result of a series of dreams he had in the immediate aftermath of Darin’s death. “About a week after he died, and for about a month or so, every night I had an intense dream about flies. This is very unusual for me. The dreams that I remember tend to be very boring: I’ll have a dream that I’m at a coffee shop, and I’ve ordered a coffee. End of dream.” Now, though, his nights were studded with human-sized “Hollywood flies”, or rooms packed with flies he had somehow to get through. Sometimes Darin appeared in them – “it was very exciting to have a sense of him, his physical body next to mine” – and then, abruptly, they stopped altogether. But their “residue” persisted, and eventually Michael began to write about them, conceding now that the dreams “might have just been a way to trick myself into addressing the subject matter in a poem”. The result is stunning, unnerving, disturbing. “At the end of one of the billion light years of loneliness”, the poem False Start begins, “My mother sits on the floor of her new kitchen carefully feeding the flies from her fingertips”.

It was Matthew Hollis, poet, award-winning biographer and poetry editor at Faber and Faber, who thought the Dickmans’ poems about their brother would work as a single volume, and, he told me, “connect far more widely than poetry sometimes does”. A long-term fan of their work, he sees in Matthew’s “long, rolling lines” the influences of Walt Whitman, Allen Ginsberg and Frank O’Hara, and in Michael’s shorter, more European-inflected work echoes of Wallace Stevens. But what united them, he was sure, was this deep, personal investment in describing their family’s loss.

The Dickmans discuss their work, and their lives, so openly and warmly that you can momentarily forget how painful it must be. How does it feel to them, to be sitting here, talking about it? “I’m very proud of this work,” says Michael, “and of this book in particular. And I also wish it never existed. So that is a strange position to be in.” Matthew agrees: “I would guess anyone who’s written about the death of a beloved would give up that book and any other book that they would ever write again just to hang out with them again.”

They’ve told me about the plays they wrote jointly, one for each of the 50 states of America (plus Puerto Rico and Guam), which began life as a scramble to help Michael finish a grad school class project that he’d left until the last minute. “I love that you call it a project!” laughs Matthew. What would he call it? “A scam!” They’ve also told me how once, when Matthew was in a college play, Michael went to watch. At the interval, Michael went to the toilet, as did the play’s director, who began to berate him for his poor performance.

Now, though, I want to ask them about the starriest experience of their careers. How did they come by their roles – as the ghostly “pre-cogs” – in Steven Spielberg’s futuristic Minority Report? They immediately pull my leg. Michael: “No one has ever asked us that.” Matthew: “It’s so weird.” I express astonishment. Michael: “I’m kidding.” OK, but how? They’re not quite sure how it came together, but after being involved in high-school and college theatre, they were briefly signed to an agency. In the first audition, they sat in fold-out chairs and shook. For the callback, they were told that Spielberg really liked their look, and “that a lot of the twins they had auditioned were really beautiful models, really handsome, like surf gods”, says Matthew.

Michael adds: “‘Spielberg loved how vacant your faces looked.’”

They roar.

Matthew: “‘Like nothing was happening inside your heads.’”

Michael: “‘Slightly weird-looking idiots!’”

They got the parts, and loved working with Spielberg, who treated them with great kindness, they say. As a thank you, they bought him a first edition of the poetry of Jewish-German Nobel prize winner Nelly Sachs, whose work the director had put on the cast and crew’s reading list during the making of Schindler’s List. Now, Spielberg asked Minority Report’s star, Samantha Morton, to hold the book, and read a poem at random to herself during the film’s closing scene, a fact that pleases them inordinately. The Dickman brothers: getting poetry into the most unexpected of places, with double piggy power.

Brother by Matthew and Michael Dickman is published by Faber, £10.99

There's a terrific Terry Kelly interview with Michael here:

And a review of Green Migraine here:

Saturday 25 June 2016

Friday 24 June 2016

Thursday 23 June 2016

Wednesday 22 June 2016

Tuesday 21 June 2016

Re-discovering Ross Macdonald

On the 100th anniversary of Ross Macdonald’s birth, Linwood Barclay reflects on the mystery writer’s work

Linwood Barclay

The Globe and Mail

1 May 2015

Ross Macdonald: Four Novels of the 1950s

Author Edited by Tom Nolan

Publisher The Library of America

Pages 926 pages

Price $43

Year 2015

Back in 1970, when I was 15 years old, my bookstore was the twirling metal stand at the Shea’s IGA in Bobcaygeon, Ont., where my parents ran a cottage resort and trailer park. This was where I’d grab an Agatha Christie novel, or the latest Nero Wolfe mystery by Rex Stout. But on this particular day, what caught my eye was the Bantam paperback edition of The Goodbye Look, a Lew Archer novel by Ross Macdonald.

Six years later, when I found myself spending an evening with the man, having dinner with him, giving him a tour of Trent University, it would dawn on me what a pivotal moment that visit to the grocery store had been.

But more about that later.

On the paperback cover was a quote from a William Goldman article in the New York Times Book Review: “The finest series of detective novels ever written by an American.” That was good enough for me. I put down 95 cents and the book was mine.

The key word in that cover blurb was “ever.” Goldman, the famous screenwriter and novelist, was clearly implying Ross Macdonald’s work had surpassed that of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. He wasn’t alone in thinking that way. In the sixties and seventies, Macdonald (whose real name was Kenneth Millar) was seen to be their successor, a novelist who’d taken the conventions of the detective novel and enriched them with psychological insight and greater moral complexity.

Since Macdonald’s death in 1983, his star has faded somewhat, while Chandler and Hammett remain literary household names. But on the 100th anniversary of Macdonald’s birth, The Library of America is taking a welcome step to ensure that his work is given proper consideration.

It has just published Ross Macdonald: Four Novels of the 1950s – The Way Some People Die, The Barbarous Coast, The Doomsters and The Galton Case. The book also includes a detailed chronology of the author’s life and a selection of articles and letters by Macdonald that offer insights into his approach to his work.

The first two novels are of the hard-boiled variety, and owe much to Chandler and Hammett. But Macdonald believed he could do better than that, particularly better than Chandler, whose loose plots were designed to create good scenes, whereas Macdonald viewed plot as a vehicle for meaning.

His approach has evolved by the time he writes The Doomsters, about an escapee from a psychiatric facility who comes to Archer for help, and The Galton Case, in which a woman engages Archer to find her long-lost son. Archer himself is rarely the story. He’s not hired by old girlfriends with long legs and ample bosoms who now find themselves in a jam. As Macdonald himself had said, Archer was so two-dimensional that if he turned sideways, he would disappear. I wouldn’t go that far. Archer feels fully realized, has a strong moral code, a sense of decency. But he is also a device, a kind of gardener who unearths dirt to allow sunshine in and expose diseased roots. Unlike the earlier novels, where Archer often tangled with common thugs, inThe Doomsters and The Galton Case the detective’s clients are more upscale, but their sins run just as deep.

The latter is seen by many as Macdonald’s masterpiece, and it may well have been at the time, but his career highs would come in later decades with The Chill, Black Money and The Underground Man. The Galton Case, however, marked a period where Macdonald mined, in a more direct way, his own life for material. It explores his feeling of displacement that came from being born in the United States but raised in Canada. Plus, there’s the theme of the absent father: Macdonald’s abandoned the family when he was a boy; in Galton, Archer is on the trail of a young man named John who’s in search of his own. (Macdonald’s father’s name was John.) Many of the 18 Archer novels, and short stories (one called, interestingly, Gone Girl), are about disappearances, and it doesn’t seem to be reading too much into things to surmise that much of Macdonald’s writing was about finding what he himself had lost.

This Library of America collection is edited by Tom Nolan, who wrote the definitive biography of the author in the late 1990s, and is co-editor of the upcoming Meanwhile There Are Letters: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and Ross Macdonald.

Macdonald was a prodigious writer of letters. I know. I have a stack of them.

I was in my late teens when I wrote to my favourite writer, who lived in Santa Barbara, Calif., ostensibly to ask if he could point me to pieces written about him – such as a Newsweek cover story – for a thesis I was intending to write for a Trent English course. When, to my joy, he replied, I wrote back and made a request I now realize was a huge imposition. Could I send him the manuscript of the detective novel I’d written? He said sure.

I’ve often wondered why. Maybe it had something to do with my letter’s postmark. Ontario had made its mark on Macdonald. He’d attended Kitchener-Waterloo Collegiate (and later taught there; writer-broadcaster June Callwood was one of his students), studied at Western, married the daughter of Kitchener’s mayor (Margaret Millar would achieve fame as a crime writer before her husband hit it big), saw his first professional work published in Toronto Saturday Night.

We had many letters back and forth covering a range of topics, including that book I’d sent him, and a second one. (Neither of those novels was ever published, and we can all be grateful for that.)

In 1976, in the lead-up to the publication of The Blue Hammer, Macdonald wrote to tell me he was coming to Canada. Maybe there would be a chance to meet in Peterborough when he was visiting with Margaret’s family. The call came on a May afternoon. I’d just finished burying the fish guts from our cottage resort’s guests’ catch. Did I want to join them for dinner?

For most other kids in this country – I never played hockey – this would be like getting a call from Bobby Orr asking if you wanted to hang out.

I raced over and found him standing outside, as though expecting me. He was dressed in a sport jacket and nice slacks, looking just like his author photo on the hardcover of Sleeping Beauty I’d brought with me. He was reserved and soft-spoken.

He asked about my family. I told him about losing my father when I was 16. It seemed to hit home. “I’m sorry,” he said.

At his request, I’d brought along a copy of the skin magazine Gallery that included an interview with him he’d not seen. He peeked into the bag, blushed, asked that I wait a minute while he went inside and tucked it away into his suitcase.

I drove him along the road that hugs the Otonabee River, gave him a walking tour of Trent. We talked about writing and other things, but I can recall almost nothing specific of what we said. I think, maybe, I was in shock. I do remember telling him, over dinner at the home of his wife’s relatives, how much I loved the low-key, opening chapter of The Underground Man, where Archer befriends a troubled young boy feeding some blue jays.

“I’ll write another one like that for you,” he said, and smiled.

Not that he actually would have, but unbeknownst to him, he’d already written his final novel. Encroaching Alzheimer’s disease would end his writing career, and seven years later, he would be dead.

In my copy of his novel Sleeping Beauty, he wrote: “For Linwood, who will, I hope, someday outwrite me. Sincerely, Kenneth Millar (Ross Macdonald).”

Perhaps as much as I treasure that inscription are these words he wrote to me in a letter dated Feb. 28, 1976:

“This is a fairly complex discipline that you and I have undertaken, and it takes time to master or be mastered by it. Something like a lifetime, in my rather slow case, but worth the time, and we make friends on the way.”

Linwood Barclay’s new novel, Broken Promise, was released in July 2015

You might also like this:

Monday 20 June 2016

Sunday 19 June 2016

Friday 17 June 2016

Van Morrison - the ten best...

Van Morrison – 10 of the best

From radio-friendly R&B via religious fervor to spiritual reawakening, these tracks map the Northern Irish songwriter’s soul-searching career

Graeme Thomson

Wednesday 1 June 2016

1. TB Sheets

During Van Morrison’s spell in Them, the brutally, brilliantly reductive Belfast band he fronted between 1964 and 1966, there had been glimmers of an artistic sensibility at odds with the turbo-boosted dockside R&B of songs like Gloria and Baby Please Don’t Go. On My Lonely Sad Eyes, Hey Girl and an aching cover of John Lee Hooker’s Don’t Look Back, Morrison was reaching for something deeper and more revelatory. It wasn’t until he made his first solo recordings in New York with Bert Berns in 1967, however, that he began forging a distinct creative identity. The antithesis of the jaunty Brown Eyed Girl, TB Sheets is the first great Morrison immersion: 10 minutes of crawling, bloodied blues, sticky with the sweet stench of decay. Taking cues from gnarled old death songs like TB Blues, Morrison conjures something entirely idiosyncratic. The “Julie baby” dying of tuberculosis was, according to various sources, either an old high school friend, his London landlady or a work of fiction. Whoever she may be, Morrison delivers us, with unremitting focus, into her fetid room, creating a suitably claustrophobic, choking musical backdrop of stabbing organ, stinging blues licks and searing harmonica. His agitated death-watch veers between compassion (“I cried for you”), impatience (“I gotta go, I’ll send somebody around later”), awkward empathy, guilt and mortal dread. When words fail, he snuffles at the window like a hunted boar. When the recording was over – apparently; perhaps apocryphally – Morrison burst into tears. Not an easy listen, but grimly unforgettable.

2. Madame George

It’s almost impossible to pick one track from the close-stitched tapestry that is Astral Weeks, where every song – excepting, perhaps, the smooth swing of The Way Young Lovers Do – makes persuasive claim to being a masterpiece. Morrison’s dreamtime evocation of postwar Belfast was recorded in a handful of hours with some of America’s finest jazz musicians, relying on intuition and alchemy to bring the songs of memory and rebirth to vivid life. Madame George exemplifies the album’s mood of heightened nostalgia, its pitch of ecstatic longing. Earlier attempts at the song recorded with Berns came out sounding boorish and flat-footed. Now working with New York producer Lewis Merenstein, Morrison and his hired hands instinctively divine the heart of it, capturing an entire street world in 10 minutes with three simple acoustic guitar chords, fluttering flute, backstreet violin and Richard Davis’s double bass, the elastic anchor which holds the whole thing together. The charismatic drag queen of the title – an amalgam of six or seven different people, according to Morrison – is a wonderfully elusive construct around whom a rich cast of characters spin. Although his lyricism has never been more colourful or evocative, the key line is a simple one: “Say goodbye.” Madame George is one long letting go: to time, place, people; above all to innocence. It ranks among the most beautiful and heartbreaking farewells in popular music.

3. Into the Mystic

Morrison followed the loose abstractions of Astral Weeks with the precise opposite – a collection of tight, honed, radio-friendly blue-eyed soul made with the crack band of local musicians he had assembled near his home in Woodstock. The 10 tracks on Moondance offer up an embarrassment of riches, but the killer cut is this mysterious tale of being “born before the wind, oh so younger than the sun”, and sailing the “bonny boat” into some sublime metaphysical harbour. Pinned down by Morrison’s rattling acoustic rhythm guitar, John Klingberg’s propulsive bass, and the totemic foghorn, Into the Mystic provides the spiritual heft on an album more concerned with transmission than transcendence. I saw him perform it a couple of years ago in Edinburgh and it still possesses a mighty pair of wings.

4. Jackie Wilson Said (I’m in Heaven When You Smile)

Morrison’s superlative run of driving R&B singles in the early 1970s – Come Running, Domino, Blue Money, Wild Night – turned him into a US pop star, a development he professed to loathe, naturally. That particular populist strain of writing peaked with this frantic, appealingly odd slice of finger-snapping soul-pop from 1972’s Saint Dominic’s Preview. Paying homage to the great American R&B star, one of the few vocal stylists who could hold a candle to the Belfast Cowboy, Morrison is at his most unaffected and exuberant. There’s no poetry here, just a string of “do-do-do-dos”, “bop-shoop-bops” and “dang-a-lang-a-langs” to express the sheer joy of being head over heels in love. Dexys Midnight Runners had the big UK hit with the song in 1982 (resulting in their infamous “Jocky Wilson” Top of the Pops performance), but Van’s remains the definitive reading. You can imagine the wee fellow high-kicking his way through it, letting it “all hang out”, and very possibly tearing the seat of his trousers in the process.

5. Listen to the Lion (live)

Morrison’s peerless double live album, It’s Too Late to Stop Now, is revisited this month in an expanded box set. Recorded during his 1973 tour, it captures him at a career peak, performing with the 11-piece Caledonia Soul Orchestra, a superlative band augmented with two horn players and a string quartet. The new material – 45 tracks – only serves to emphasise the jaw-dropping power and versatility of Morrison in full flood. It includes two previously unheard versions of Listen To the Lion, his epic incantation from Saint Dominic’s Preview; the one recorded at the Rainbow in London just about shades it for sheer vocal abandon, not to mention Bill Atwood’s soaring trumpet part. The song itself is the ultimate expression of Morrison’s compulsion to heed the internal voices that drive his music, the seemingly painful search for his inner lion. Over a slow, stop-start shuffle, the words are pared to a bare minimum. “I will search my very soul,” is the digested read; this is all about sound and feel. Many years later Morrison described it as “a song about me. Probably the only one”.

6. Streets of Arklow

After moving to America in 1967, Morrison spent the next six years in exile from Ireland. On his return in 1973 for a holiday, he immediately found the muse rapping at his window. He flew back to his home near San Francisco with a hatful of strange and beautiful songs, infused with Celtic twilight and preoccupied with a grail-like object that gave his next album its title but the significance of which even Morrison has since been unable to adequately explain. Reminiscent of Astral Weeks in its instrumentation, flow and questing spirit, Veedon Fleece is one of his greatest works. Any selection from the album is bound to be representative rather than definitive, but this brooding, contemplative march is a highlight, inspired by Morrison’s visit to the Wicklow town of Arklow, his head “full of poetry”. James Rothermel’s high, lyrical recorder soars over “God’s green land”, and when the strings swoop in at the start of the third verse, the force of the music perfectly conveys the gravitas of Morrison’s “soul-cleansing” excursion.

7. Full Force Gale

Following a directionless mid-to-late 1970s, Morrison wrapped up the decade with one of his most enjoyable albums, Into the Music, a breezy declaration of spiritual and musical regeneration. With a sensational new band, spearheaded by former James Brown horn player Pee Wee Ellis and freewheeling violinist Toni Marcus, he hit upon a powerful folk-soul hybrid which on the album culminated in a monumental 11-minute version of the 1950s standard It’s All in the Game. Van’s more accessible musical instincts were also back on track. The one-two punch of Bright Side of the Road (a minor hit in the UK) and this rousing declaration of being “returned to the Lord” is one of Morrison’s most uplifting opening sequences, and the most effortlessly immediate music he had made since the days of Brown Eyed Girl. Whether or not you care for the God-talk, Full Force Gale is an irresistible expression of rebirth, a punchy pop gospel testament which sweeps away any doubters.

8. Summertime in England

This 15-minute excursion from 1980s meditative Common One became the fulcrum of Morrison’s live shows for the next decade, an open-ended opportunity for the band to vamp and for he and Ellis to engage in extended call-and-response routines about topics as obscure as brass bands and Seamus Heaney’s publisher. Summertime in England is the deepest of Deep Van, an improvised jumble of some of Morrison’s most pressing musical, spiritual and literary preoccupations. Partly inspired by the open spaces of Miles Davis’s In a Silent Way, it’s a deeply ambitious, highly eccentric, improvised blend of snappy rhythm, hymn-like half-time passages, funky organ, vaulting strings and free-flowing horns. The action moves from the Lakes to the Vale of Avalon as Morrison pictures Wordsworth and Coleridge “smokin’ up in Kendal”, evokes Mahalia Jackson coming “through the ether”, pays homage to Yeats, Joyce, Eliot and, of course, William Blake, and eulogises about a woman in a red robe – “high in the art of sufferin’” – with whom he plans an assignation in the long grass. The conclusion of all this magnificent madness? “It ain’t why, why, why – it just is.” Amen.

9. In the Garden

Van’s last full-length masterpiece was No Guru, No Method, No Teacher, released 30 years ago. From its pointed title onward it found him shucking off many of the formal teachings that had infiltrated his music over the past several years – Christianity, Scientology, Rosicrucianism – to reconnect with his enduring muses: nature, pantheistic spirituality and a deep absorption with the past. In the Garden brings all three themes together in six minutes of pure rapture. Morrison transports himself back to “the garden wet with rain” of Astral Weeks, taking the listener, trancelike, through what he later described as “a meditative process”. The music is unspeakably gorgeous, a wonderfully tensile ensemble performance lead by Jef Labes’ rippling piano motif, every quiver held in check through to the ecstatic climax, where Morrison turns the album title into a mantra. Though he tends to favour more workmanlike material in concert these days, this remains the transcendent high point of Morrison’s recent live appearances.

10. Coney Island

Before Morrison’s long slide into genre exercises – a skiffle album here, a country record there, jazzin’ at Ronnie Scott’s – and the undistinguished collections of too-solid blues and R&B that have defined his music over the past two decades, he enjoyed a late-80s commercial renaissance with Avalon Sunset. The album marks the lush, string-drenched apogee of his preoccupation with a peculiarly British strain of ancient mysticism. Forget the singularly unlikely Cliff Richard duet (Whenever God Shines His Light) which finally got The Man on Top of the Pops, and head instead to this magnificent miniature Coney Island is an orchestrated gem over which Morrison recites – in thick east Belfast vernacular; check out the way he says “face” – an autumn bird-watching trip through the County Down where the “craic was good” and so, apparently, was the grub: “Stop off at Ardglass for a couple of jars of mussels and some potted herrings, in case we get famished before dinner”. Somebody once tracked the route taken in the song and concluded that Morrison must have deployed William Burroughs’ cut-up technique on his road map, but such literalism misses the point. This is a journey into the heart of life’s simple joys, a note-to-self to seize contentment when it appears, even in such seemingly mundane pleasures as “stopping off for Sunday papers at the Lecale District”. A mere 123 seconds it may be, but Morrison’s eternally restless soul has rarely sounded at such peace. “Wouldn’t it be great if it was like this all the time?”

Hard to pick just ten, I know, and I could quite easily go for all of Into the Music, but mine would include Angeliou, The Street Only Knew Your Name (but the version on Philosopher's Stone not the version on Inarticulate Speech of the Heart that seems smothered in the production and not sung with as much gusto), St Dominic's Preview, Caravan (but it has to be the version from The Last Waltz, silly outfit and all), Ancient Highway, Celtic Ray (the version of Beautiful Vision), Sweet Thing, Warm Love, Wild Night, Cold Wind in August (from the deeply - and wrongly - unfashionable Period of Transition).

There, that's ten, isn't it?

Wednesday 15 June 2016

Tuesday 14 June 2016

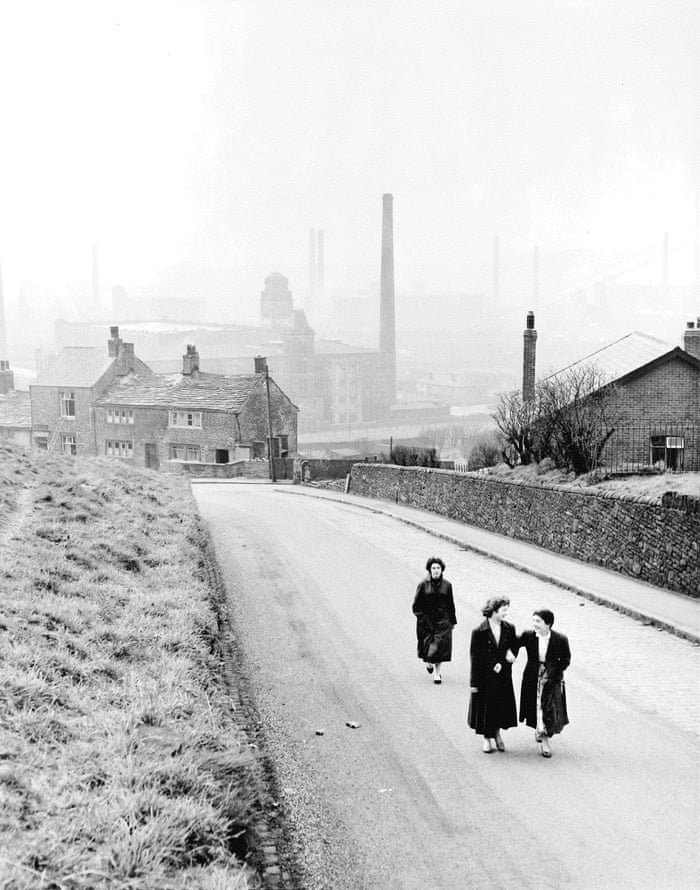

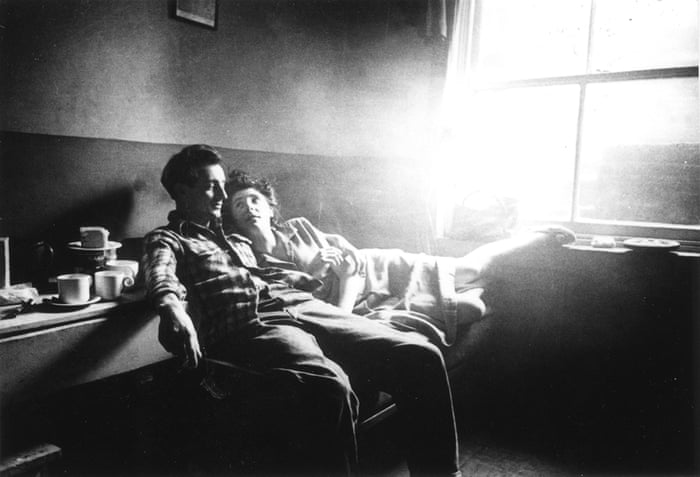

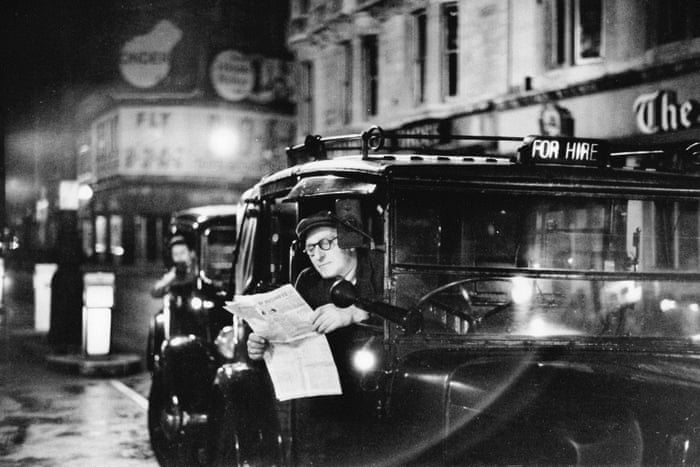

Bert Hardy: Photographs of Britain in the mid-century

Teachers (1956)

Teenagers (1957)

Cockney Life at the Elephant and Castle (1949)

Pool of London (1949)

Sugar Ray Robinson (1951)

Piccadilly (1953)

Piccadilly (1953)

Royal Wedding (1947)

Gorbals (1948)

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/jun/09/never-had-it-so-good-bert-hardys-archive-of-mid-century-life-in-pictures

Monday 13 June 2016

The Battle of the Somme and The War Film

How The Battle of the Somme sparked cinema’s obsession with war

One hundred years after the battle of the Somme and the groundbreaking film that followed, Laura Clouting explores the challenges of dramatising the fear, courage and complicated reality of going into combatLaura Clouting

Friday 10 June 2016

In a few weeks’ time, 100 years will have passed since the first day of the battle of the Somme. Tens of thousands of soldiers went “over the top” at 7.30am on 1 July 1916. The moment looms large in the collective national memory – nearly 20,000 British soldiers died that day, just the first of the “big push” that continued into the winter months.

The ferocious offensive drew on Britain’s imperial forces, and was the bloody debut of civilian volunteers who had flooded recruitment halls in 1914. Among them were two individuals who weren’t there to fight, yet were profoundly influential in shaping our vision of the conflict. Cameramen Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell were in France to record the footage that went on to become the cinematic sensation The Battle of the Somme, the film that sparked cinema’s obsession with war. Now, a new exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London explores the inspiration behind some of the best-known war movies, the craft of reconstructing the extreme environments in which fighting occurs, and why audiences remain enthralled by the genre; from the desert epic Lawrence of Arabia to Apocalypse Now’s jungle insanity in Vietnam.

At the turn of the 20th century, short films were a fairground novelty. Their popularity lead to purpose-built cinemas, but they remained largely the preserve of the working class. With the onset of war, what had seemed faddish gained traction. Craving news from the fronts, British audiences flocked to the cinema for a sense of immediacy that no newspaper report, photograph, or illustration could rival. The cinema acquired a degree of legitimacy and across the social spectrum people welcomed the narrative-driven perspective that film offered.

The Battle of the Somme was, in some ways, a surprise to both its makers and its audience. When Malins was dispatched to the western front in November 1915, he was charged with shooting footage for use in short newsreels. Neither the War Office nor Malins’s cinema trade employers expected a feature film. In late June 1916 Malins was joined by his assistant McDowell, and together they turned their cameras towards the British army gearing up for, and then launching, the largest battle it had ever fought. When their reels arrived in London, the decision was made to present the silent footage as a feature film, often accompanied by an unexpectedly jaunty score played by musicians in cinemas.

The finished film had an extraordinary impact. When it was released in August 1916, audiences were stunned by the feeling that they had witnessed the battle for themselves. It begins with the buildup. Mountains of munitions and thousands of men deluge the frontline in readiness. German defences are smashed by British guns. Yet to give these real scenes a coherent narrative, the film needed climactic images of men going over the top. Loaded down with cumbersome equipment, the cameramen were unable to capture this crucial moment and resorted to fakery. They staged troops leaping over their trench parapet and stepping through barbed wire before disappearing into a smokescreen. These shots had a tremendous impact in the cinema, with audiences cheering the men. There are reports of a woman crying out “Oh God, they’re dead!” at the “deaths” played out for the camera alongside unflinching real shots of the dead and wounded.

However, look closely and the staged shot gives itself away. Some scenes are believed to have been filmed at a school near St Pol, over 25 miles away, about a month later. In this footage men go into action unencumbered by the weighty packs that real soldiers had to shoulder. With just a rifle in his hand, one man drops “dead” in front of barbed wire – and proceeds to cross his legs to get more comfortable on the ground. Most telling is the camera position. Had Malins or McDowell really been filming from this angle they would have been in considerable danger from German fire. But the audience had no reason to doubt the authenticity of the footage. The Battle of the Somme’s imagery has come to represent the conflict as a whole, and paved the way for what we might think of as a “war film” – a fictional reconstruction of a real event. The tension between dramatic effect and recording the “reality” of war has troubled film-makers ever since, in both feature film and documentaries.

In 1942, the film-making duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger made One of Our Aircraft is Missing, a story of a British bomber crew shot down over the Netherlands. Following a screening in March 1942, an excited Powell telegraphed Pressburger: “After Glasgow showing no doubt whatever that picture has most extraordinary effect on audiences creating lasting impression of truth and reality.” What does it mean to capture truth and reality, and why do war films, perhaps more than most other genres, often claim to tell “the real story”?

In 1946 Brian Desmond Hurst directed Theirs Is the Glory, a film recounting the British army’s bloody and unsuccessful airborne assault on the Dutch town of Arnhem in 1944. During the battle, Major Richard Lonsdale of 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, delivered a rousing speech to his men at a battered church. For the film, Lonsdale appeared as himself, delivering the same speech, at the same church, to hundreds of soldiers who had also fought at Arnhem. This time his severe wounds were merely costume and makeup, but the effect is striking.Theirs Is the Glory made extensive use of battle footage taken by parachute-trained cameramen of the Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU), and blurred the line between reality and reconstruction.

The AFPU captured scenes on British fighting fronts throughout the second world war, and comparisons can be made with fictional depictions of the same episodes. IWM’s film historian and archivist Dr Toby Haggith has watched both AFPU’s footage of the D-day landings and the scenes from Steven Spielberg’s 1998 Saving Private Ryan. Intriguingly, he has noted that while Spielberg shows us soldiers trembling with nervous anticipation, the real soldiers filmed aboard their landing craft struck confident, even heroic poses, refusing to allow themselves to appear scared. Interpreting this as a kind of dramatic performance, Haggith asked: “If real soldiers act in front of the camera, how should actors portray reality?” In other films professional actors brought additional ambiguity because they had once been soldiers, sailors or airmen themselves. When Richard Todd, a paratroop officer on D-day, was cast in The Longest Day (1962), he found himself playing Major Howard of the glider-borne “Ox and Bucks” light infantry, someone he had met during the real invasion.

Todd was one of a generation of British actors who became household names for their roles in a stream of 50s war films. John Mills, Kenneth More and Jack Hawkins, in films such as The Cruel Sea (1953), Reach for the Sky (1956), Ice Cold in Alex (1958) and The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), embodied ideals of leadership and courage – and a dash of eccentricity. The heroics of female agents Odette Sansom and Violette Szabo were depicted by Anna Neagle in Odette (1950) and Virginia McKenna in Carve Her Name With Pride (1958).

Of this generation of films, it is perhaps Michael Anderson’s The Dam Busters (1955) that is best remembered, both for Todd’s portrayal of bomber pilot Guy Gibson and its rousing, martial theme by composer Eric Coates. The power of music to manipulate an audience often transcended a film’s subject matter. “The Dam Busters March” today resounds around football stadia and Elmer Bernstein’s score for The Great Escape was recently appropriated during the EU referendum campaign, with Bernstein’s sons protesting against the use of their father’s music by Ukip.

In the aftermath of the second world war, this wave of films helped to contextualise the continuing austerity in postwar Britain with tales imbued with clear moral certainty. They reflect the place the war holds in Britain’s national identity. In Germany, however, nearly six decades passed before a home-produced depiction of Adolf Hitler made it into the cinema. In 2004, director Oliver Hirschbiegel’s Downfall dramatised the last days of Hitler’s Führerbunker beneath ravaged Berlin. German-speaking Swiss actor Bruno Ganz played Hitler with a manner that many found “chillingly authentic”. The film sparked debate as to how far a film-maker or artist should go in humanising a historical figure who committed appalling crimes. The historian Ian Kershaw asked in this newspaper, “Wasn’t there the danger, in seeing Hitler as a human being, of losing sight of his intrinsic evil and monstrous, demonic nature, even of arousing sympathy for him?”. Ganz’s performance has gone on to be parodied mercilessly online, re-subtitled to show Hitler ranting against petty injustices from unwelcome sporting results and poor customer service. Hirschbiegel endorsed these parodies, saying that they further the film’s purpose of kicking “these terrible people off the throne that made them demons”.

But not all films have been as concerned with realism. In Dr Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Stanley Kubrick brutally satirised the madness that the strategy of nuclear “mutually assured destruction” implied. Richard Attenborough’s adaptation of Oh! What a Lovely War (1969) rendered cavalry charges as carousel rides. In it, the battle of the Somme is summed up by a scoreboard that ultimately declares: “Allied losses – 600,000. Ground gained – Nil.”

• Real to Reel: A Century of War Movies, curated by Laura Clouting, opens on 1 July at the Imperial War Museum, London SE1. iwm.org.uk/real-to-reel.

Moy and Bastie cine camera, of the type used to capture real and recreated footage for the wartime cinema sensation The Battle of the Somme © Courtesy of The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, University of Exeter

Real to Reel: A Century of War Movies

IWM London

Coming soon: 1 July 2016 – 8 January 2017

Go behind the scenes of some of the most iconic war films which have captured the imagination of cinema-going audiences for generations.

To mark the 100th anniversary of the release of the original blockbuster, The Battle of the Somme, this immersive new exhibition will explore how film-makers have found inspiration from war's inherent drama to translate stories of love and loss, fear and courage, triumph and tragedy into movies for the big screen.

Colour storyboard artwork of the famous helicopter attack scene from Apocalypse Now, which was set to the music of Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries. © Courtesy of American Zoetrope

Discover personal stories and surviving wartime artefacts alongside film industry props, scripts and set designs from classics including The Dam Busters, Where Eagles Dare, Apocalypse Now, Battle of Britain, Das Boot, Casablanca, Jarhead, Saving Private Ryan, Atonement and War Horse, among many more, to reveal how box-office hits can offer surprising perspectives on war.

IWM London

Coming soon: 1 July 2016 – 8 January 2017

Go behind the scenes of some of the most iconic war films which have captured the imagination of cinema-going audiences for generations.

To mark the 100th anniversary of the release of the original blockbuster, The Battle of the Somme, this immersive new exhibition will explore how film-makers have found inspiration from war's inherent drama to translate stories of love and loss, fear and courage, triumph and tragedy into movies for the big screen.

Colour storyboard artwork of the famous helicopter attack scene from Apocalypse Now, which was set to the music of Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries. © Courtesy of American Zoetrope

Discover personal stories and surviving wartime artefacts alongside film industry props, scripts and set designs from classics including The Dam Busters, Where Eagles Dare, Apocalypse Now, Battle of Britain, Das Boot, Casablanca, Jarhead, Saving Private Ryan, Atonement and War Horse, among many more, to reveal how box-office hits can offer surprising perspectives on war.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![[IMG]](https://66.media.tumblr.com/2d20f409c8ee2790b351f7ab139e94af/tumblr_nkp5a7gKlj1s7ifuuo1_500.gif)