By Jonathan Kandell and Andy Webster

The New York Times

12 Nov. 2018

If Stan Lee revolutionized the comic book world in the 1960s, which he did, he left as big a stamp — maybe bigger — on the even wider pop culture landscape of today.

Think of “Spider-Man,” the blockbuster movie franchise and Broadway spectacle. Think of “Iron Man,” another Hollywood gold-mine series personified by its star, Robert Downey Jr. Think of “Black Panther,” the box-office superhero smash that shattered big screen racial barriers in the process.

And that is to say nothing of the Hulk, the X-Men, Thor and other film and television juggernauts that have stirred the popular imagination and made many people very rich.

If all that entertainment product can be traced to one person, it would be Stan Lee, who died in Los Angeles on Monday at 95. From a cluttered office on Madison Avenue in Manhattan in the 1960s, he helped conjure a lineup of pulp-fiction heroes that has come to define much of popular culture in the early 21st century.

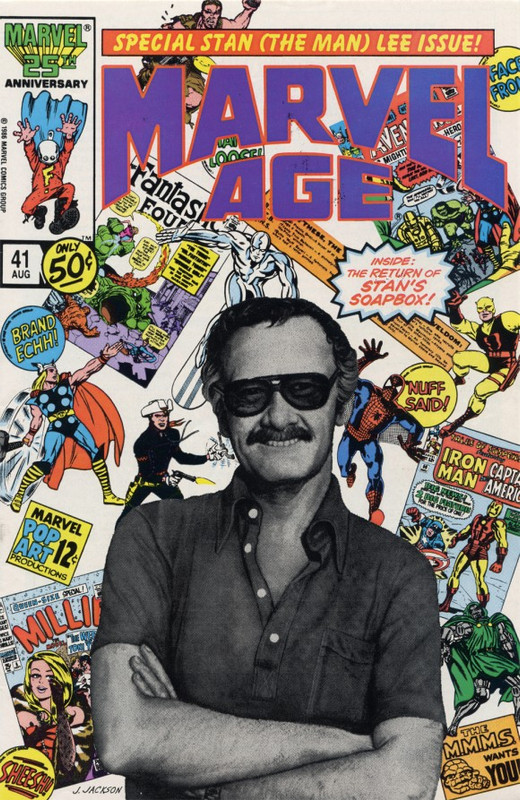

Mr. Lee was a central player in the creation of those characters and more, all properties of Marvel Comics. Indeed, he was for many the embodiment of Marvel, if not comic books in general, overseeing the company’s emergence as an international media behemoth. A writer, editor, publisher, Hollywood executive and tireless promoter (of Marvel and of himself), he played a critical role in what comics fans call the medium’s silver age.

Many believe that Marvel, under his leadership and infused with his colorful voice, crystallized that era, one of exploding sales, increasingly complex characters and stories, and growing cultural legitimacy for the medium. (Marvel’s chief competitor at the time, National Periodical Publications, now known as DC — the home of Superman and Batman, among other characters — augured this period, with its 1956 update of its superhero the Flash, but did not define it.

Under Mr. Lee, Marvel transformed the comic book world by imbuing its characters with the self-doubts and neuroses of average people, as well an awareness of trends and social causes and, often, a sense of humor.

In humanizing his heroes, giving them character flaws and insecurities that belied their supernatural strengths, Mr. Lee tried “to make them real flesh-and-blood characters with personality,” he told The Washington Post in 1992.

That’s what any story should have, but comics didn’t have until that point,” he said. “They were all cardboard figures.”

Energetic, gregarious, optimistic and alternately grandiose and self-effacing, Mr. Lee was an effective salesman, employing a Barnumesque syntax in print (“Face front, true believer!” “Make mine Marvel!”) to market Marvel’s products to a rabid following.

He charmed readers with jokey, conspiratorial comments and asterisked asides in narrative panels, often referring them to previous issues. In 2003 he told The Los Angeles Times, “I wanted the reader to feel we were all friends, that we were sharing some private fun that the outside world wasn’t aware of.”

Though Mr. Lee was often criticized for his role in denying rights and royalties to his artistic collaborators , his involvement in the conception of many of Marvel’s best-known characters is indisputable.

If Stan Lee revolutionized the comic book world in the 1960s, which he did, he left as big a stamp — maybe bigger — on the even wider pop culture landscape of today.

Think of “Spider-Man,” the blockbuster movie franchise and Broadway spectacle. Think of “Iron Man,” another Hollywood gold-mine series personified by its star, Robert Downey Jr. Think of “Black Panther,” the box-office superhero smash that shattered big screen racial barriers in the process.

And that is to say nothing of the Hulk, the X-Men, Thor and other film and television juggernauts that have stirred the popular imagination and made many people very rich.

If all that entertainment product can be traced to one person, it would be Stan Lee, who died in Los Angeles on Monday at 95. From a cluttered office on Madison Avenue in Manhattan in the 1960s, he helped conjure a lineup of pulp-fiction heroes that has come to define much of popular culture in the early 21st century.

Mr. Lee was a central player in the creation of those characters and more, all properties of Marvel Comics. Indeed, he was for many the embodiment of Marvel, if not comic books in general, overseeing the company’s emergence as an international media behemoth. A writer, editor, publisher, Hollywood executive and tireless promoter (of Marvel and of himself), he played a critical role in what comics fans call the medium’s silver age.

Many believe that Marvel, under his leadership and infused with his colorful voice, crystallized that era, one of exploding sales, increasingly complex characters and stories, and growing cultural legitimacy for the medium. (Marvel’s chief competitor at the time, National Periodical Publications, now known as DC — the home of Superman and Batman, among other characters — augured this period, with its 1956 update of its superhero the Flash, but did not define it.

Under Mr. Lee, Marvel transformed the comic book world by imbuing its characters with the self-doubts and neuroses of average people, as well an awareness of trends and social causes and, often, a sense of humor.

In humanizing his heroes, giving them character flaws and insecurities that belied their supernatural strengths, Mr. Lee tried “to make them real flesh-and-blood characters with personality,” he told The Washington Post in 1992.

That’s what any story should have, but comics didn’t have until that point,” he said. “They were all cardboard figures.”

Energetic, gregarious, optimistic and alternately grandiose and self-effacing, Mr. Lee was an effective salesman, employing a Barnumesque syntax in print (“Face front, true believer!” “Make mine Marvel!”) to market Marvel’s products to a rabid following.

He charmed readers with jokey, conspiratorial comments and asterisked asides in narrative panels, often referring them to previous issues. In 2003 he told The Los Angeles Times, “I wanted the reader to feel we were all friends, that we were sharing some private fun that the outside world wasn’t aware of.”

Though Mr. Lee was often criticized for his role in denying rights and royalties to his artistic collaborators , his involvement in the conception of many of Marvel’s best-known characters is indisputable.

Reading Shakespeare at 10

He was born Stanley Martin Lieber on Dec. 28, 1922, in Manhattan, the older of two sons born to Jack Lieber, an occasionally employed dress cutter, and Celia (Solomon) Lieber, both immigrants from Romania. The family moved to the Bronx.

Stanley began reading Shakespeare at 10 while also devouring pulp magazines, the novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mark Twain, and the swashbuckler movies of Errol Flynn.

He graduated at 17 from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and aspired to be a writer of serious literature. He was set on the path to becoming a different kind of writer when, after a few false starts at other jobs, he was hired at Timely Publications, a company owned by Martin Goodman, a relative who had made his name in pulp magazines and was entering the comics field.

Mr. Lee was initially paid $8 a week as an office gofer. Eventually he was writing and editing stories, many in the superhero genre.

At Timely he worked with the artist Jack Kirby (1917-94), who, with a writing partner, Joe Simon, had created the hit character Captain America, and who would eventually play a vital role in Mr. Lee’s career. When Mr. Simon and Mr. Kirby, Timely’s hottest stars, were lured away by a rival company, Mr. Lee was appointed chief editor.

As a writer, Mr. Lee could be startlingly prolific. “Almost everything I’ve ever written I could finish at one sitting,” he once said. “I’m a fast writer. Maybe not the best, but the fastest.”

Mr. Lee used several pseudonyms to give the impression that Marvel had a large stable of writers; the name that stuck was simply his first name split in two. (In the 1970s, he legally changed Lieber to Lee.)

During World War II, Mr. Lee wrote training manuals stateside in the Army Signal Corps while moonlighting as a comics writer. In 1947, he married Joan Boocock, a former model who had moved to New York from her native England.

His daughter Joan Celia Lee, who is known as J. C., was born in 1950; another daughter, Jan, died three days after birth in 1953. Mr. Lee’s wife died in 2017.

A lawyer for Ms. Lee, Kirk Schenck, confirmed Mr. Lee’s death, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

In addition to his daughter, he is survived by Ms. Lee and his younger brother, Larry Lieber, who drew the “Amazing Spider-Man” syndicated newspaper strip for years.

In the mid-1940s, the peak of the golden age of comic books, sales boomed. But later, as plots and characters turned increasingly lurid (especially at EC, a Marvel competitor that published titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror), many adults clamored for censorship. In 1954, a Senate subcommittee led by the Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver held hearings investigating allegations that comics promoted immorality and juvenile delinquency.

Feeding the senator’s crusade was the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s 1954 anti-comics jeremiad, “Seduction of the Innocent.” Among other claims, the book contended that DC’s “Batman stories” — featuring the team of Batman and Robin — were “psychologically homosexual.”

Choosing to police itself rather than accept legislation, the comics industry established the Comics Code Authority to ensure wholesome content. Gore and moral ambiguity were out, but so largely were wit, literary influences and attention to social issues. Innocuous cookie-cutter exercises in genre were in.

Many found the sanitized comics boring, and — with the new medium of television providing competition — readership, which at one point had reached 600 million sales annually, declined by almost three-quarters within a few years.

With the dimming of superhero comics’ golden age, Mr. Lee tired of grinding out generic humor, romance, western and monster stories for what had by then become Atlas Comics. Reaching a career impasse in his 30s, he was encouraged by his wife to write the comics he wanted to, not merely what was considered marketable. And Mr. Goodman, his boss, spurred by the popularity of a rebooted Flash (and later Green Lantern) at DC, wanted him to revisit superheroes.

Mr. Lee took Mr. Goodman up on his suggestion, but he carried its implications much further.

He was born Stanley Martin Lieber on Dec. 28, 1922, in Manhattan, the older of two sons born to Jack Lieber, an occasionally employed dress cutter, and Celia (Solomon) Lieber, both immigrants from Romania. The family moved to the Bronx.

Stanley began reading Shakespeare at 10 while also devouring pulp magazines, the novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mark Twain, and the swashbuckler movies of Errol Flynn.

He graduated at 17 from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and aspired to be a writer of serious literature. He was set on the path to becoming a different kind of writer when, after a few false starts at other jobs, he was hired at Timely Publications, a company owned by Martin Goodman, a relative who had made his name in pulp magazines and was entering the comics field.

Mr. Lee was initially paid $8 a week as an office gofer. Eventually he was writing and editing stories, many in the superhero genre.

At Timely he worked with the artist Jack Kirby (1917-94), who, with a writing partner, Joe Simon, had created the hit character Captain America, and who would eventually play a vital role in Mr. Lee’s career. When Mr. Simon and Mr. Kirby, Timely’s hottest stars, were lured away by a rival company, Mr. Lee was appointed chief editor.

As a writer, Mr. Lee could be startlingly prolific. “Almost everything I’ve ever written I could finish at one sitting,” he once said. “I’m a fast writer. Maybe not the best, but the fastest.”

Mr. Lee used several pseudonyms to give the impression that Marvel had a large stable of writers; the name that stuck was simply his first name split in two. (In the 1970s, he legally changed Lieber to Lee.)

During World War II, Mr. Lee wrote training manuals stateside in the Army Signal Corps while moonlighting as a comics writer. In 1947, he married Joan Boocock, a former model who had moved to New York from her native England.

His daughter Joan Celia Lee, who is known as J. C., was born in 1950; another daughter, Jan, died three days after birth in 1953. Mr. Lee’s wife died in 2017.

A lawyer for Ms. Lee, Kirk Schenck, confirmed Mr. Lee’s death, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

In addition to his daughter, he is survived by Ms. Lee and his younger brother, Larry Lieber, who drew the “Amazing Spider-Man” syndicated newspaper strip for years.

In the mid-1940s, the peak of the golden age of comic books, sales boomed. But later, as plots and characters turned increasingly lurid (especially at EC, a Marvel competitor that published titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror), many adults clamored for censorship. In 1954, a Senate subcommittee led by the Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver held hearings investigating allegations that comics promoted immorality and juvenile delinquency.

Feeding the senator’s crusade was the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s 1954 anti-comics jeremiad, “Seduction of the Innocent.” Among other claims, the book contended that DC’s “Batman stories” — featuring the team of Batman and Robin — were “psychologically homosexual.”

Choosing to police itself rather than accept legislation, the comics industry established the Comics Code Authority to ensure wholesome content. Gore and moral ambiguity were out, but so largely were wit, literary influences and attention to social issues. Innocuous cookie-cutter exercises in genre were in.

Many found the sanitized comics boring, and — with the new medium of television providing competition — readership, which at one point had reached 600 million sales annually, declined by almost three-quarters within a few years.

With the dimming of superhero comics’ golden age, Mr. Lee tired of grinding out generic humor, romance, western and monster stories for what had by then become Atlas Comics. Reaching a career impasse in his 30s, he was encouraged by his wife to write the comics he wanted to, not merely what was considered marketable. And Mr. Goodman, his boss, spurred by the popularity of a rebooted Flash (and later Green Lantern) at DC, wanted him to revisit superheroes.

Mr. Lee took Mr. Goodman up on his suggestion, but he carried its implications much further.

Enter the Fantastic Four

In 1961, Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby — whom he had brought back years before to the company, now known as Marvel — produced the first issue of The Fantastic Four, about a superpowered team with humanizing dimensions: nonsecret identities, internal squabbles and, in the orange-rock-skinned Thing, self-torment. It was a hit.

Other Marvel titles — like the Lee-Kirby creation The Incredible Hulk, a modern Jekyll-and-Hyde story about a decent man transformed by radiation into a monster — offered a similar template. The quintessential Lee hero, introduced in 1962 and created with the artist Steve Ditko (1927-2018), was Spider-Man.

A timid high school intellectual who gained his powers when bitten by a radioactive spider, Spider-Man was prone to soul-searching, leavened with wisecracks — a key to the character’s lasting popularity across multiple entertainment platforms, including movies and a Broadway musical.

Mr. Lee’s dialogue encompassed Catskills shtick, like Spider-Man’s patter in battle; Elizabethan idioms, like Thor’s; and working-class Lower East Side swagger, like the Thing’s. It could also include dime-store poetry, as in this eco-oratory about humans, uttered by the Silver Surfer, a space alien:

“And yet — in their uncontrollable insanity — in their unforgivable blindness — they seek to destroy this shining jewel — this softly spinning gem — this tiny blessed sphere — which men call Earth!”

Mr. Lee practiced what he called the Marvel method: Instead of handing artists scripts to illustrate, he summarized stories and let the artists draw them and fill in plot details as they chose. He then added sound effects and dialogue. Sometimes he would discover on penciled pages that new characters had been added to the narrative. Such surprises (like the Silver Surfer, a Kirby creation and a Lee favorite) would lead to questions of character ownership.

Mr. Lee was often faulted for not adequately acknowledging the contributions of his illustrators, especially Mr. Kirby. Spider-Man became Marvel’s best-known property, but Mr. Ditko, its co-creator, quit Marvel in bitterness in 1966. Mr. Kirby, who visually designed countless characters, left in 1969. Though he reunited with Mr. Lee for a Silver Surfer graphic novel in 1978, their heyday had ended.

Many comic fans believe that Mr. Kirby was wrongly deprived of royalties and original artwork in his lifetime, and for years the Kirby estate sought to acquire rights to characters that Mr. Kirby and Mr. Lee had created together. Mr. Kirby’s heirs were long rebuffed in court on the grounds that he had done “work for hire” — in other words, that he had essentially sold his art without expecting royalties.

In September 2014, Marvel and the Kirby estate reached a settlement. Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby now both receive credit on numerous screen productions based on their work.

A timid high school intellectual who gained his powers when bitten by a radioactive spider, Spider-Man was prone to soul-searching, leavened with wisecracks — a key to the character’s lasting popularity across multiple entertainment platforms, including movies and a Broadway musical.

Mr. Lee’s dialogue encompassed Catskills shtick, like Spider-Man’s patter in battle; Elizabethan idioms, like Thor’s; and working-class Lower East Side swagger, like the Thing’s. It could also include dime-store poetry, as in this eco-oratory about humans, uttered by the Silver Surfer, a space alien:

“And yet — in their uncontrollable insanity — in their unforgivable blindness — they seek to destroy this shining jewel — this softly spinning gem — this tiny blessed sphere — which men call Earth!”

Mr. Lee practiced what he called the Marvel method: Instead of handing artists scripts to illustrate, he summarized stories and let the artists draw them and fill in plot details as they chose. He then added sound effects and dialogue. Sometimes he would discover on penciled pages that new characters had been added to the narrative. Such surprises (like the Silver Surfer, a Kirby creation and a Lee favorite) would lead to questions of character ownership.

Mr. Lee was often faulted for not adequately acknowledging the contributions of his illustrators, especially Mr. Kirby. Spider-Man became Marvel’s best-known property, but Mr. Ditko, its co-creator, quit Marvel in bitterness in 1966. Mr. Kirby, who visually designed countless characters, left in 1969. Though he reunited with Mr. Lee for a Silver Surfer graphic novel in 1978, their heyday had ended.

Many comic fans believe that Mr. Kirby was wrongly deprived of royalties and original artwork in his lifetime, and for years the Kirby estate sought to acquire rights to characters that Mr. Kirby and Mr. Lee had created together. Mr. Kirby’s heirs were long rebuffed in court on the grounds that he had done “work for hire” — in other words, that he had essentially sold his art without expecting royalties.

In September 2014, Marvel and the Kirby estate reached a settlement. Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby now both receive credit on numerous screen productions based on their work.

Turning to Live Action

Mr. Lee moved to Los Angeles in 1980 to develop Marvel properties, but most of his attempts at live-action television and movies were disappointing. (The series “The Incredible Hulk,” seen on CBS from 1978 to 1982, was an exception.)

Avi Arad, an executive at Toy Biz, a company in which Marvel had bought a controlling interest, began to revive the company’s Hollywood fortunes, particularly with an animated “X-Men” series on Fox, which ran from 1992 to 1997. (Its success helped pave the way for the live-action big-screen “X-Men” franchise, which has flourished since its first installment, in 2000.)

In the late 1990s, Mr. Lee was named chairman emeritus at Marvel and began to explore outside projects. While his personal appearances (including charging fans $120 for an autograph) were one source of income, later attempts to create wholly owned superhero properties foundered. Stan Lee Media, a digital content start-up, crashed in 2000 and landed his business partner, Peter F. Paul, in prison for securities fraud. (Mr. Lee was never charged.)

In 2001, Mr. Lee started POW! Entertainment (the initials stand for “purveyors of wonder”), but he received almost no income from Marvel movies and TV series until he won a court fight with Marvel Enterprises in 2005, leading to an undisclosed settlement costing Marvel $10 million. In 2009, the Walt Disney Company, which had agreed to pay $4 billion to acquire Marvel, announced that it had paid $2.5 million to increase its stake in POW!

In Mr. Lee’s final years, after the death of his wife, the circumstances of his business affairs and contentious financial relationship with his surviving daughter attracted attention in the news media. In 2018, Mr. Lee was embroiled in disputes with POW!, and The Daily Beast and The Hollywood Reporter ran accounts of fierce infighting among Mr. Lee’s daughter, household staff and business advisers. The Hollywood Reporter claimed “elder abuse.”

In February 2018, Mr. Lee signed a notarized document declaring that three men — a lawyer, a caretaker of Mr. Lee’s and a dealer in memorabilia — had “insinuated themselves into relationships with J. C. for an ulterior motive and purpose,” to “gain control over my assets, property and money.” He later withdrew his claim, but longtime aides of his — an assistant, an accountant and a housekeeper — were either dismissed or greatly limited in their contact with him.

In a profile in The New York Times in April, a cheerful Mr. Lee said, “I’m the luckiest guy in the world,” adding that “my daughter has been a great help to me” and that “life is pretty good” — although he admitted in that same interview, “I’ve been very careless with money.”

Marvel movies, however, have proved a cash cow for major studios, if not so much for Mr. Lee. With the blockbuster “Spider-Man” in 2002, Marvel superhero films hit their stride. Such movies (including franchises starring Iron Man, Thor and the superhero team the Avengers, to name but three) together had grossed more than $24 billion worldwide as of April.

“Black Panther,” the first Marvel movie directed by an African-American (Ryan Coogler) and starring an almost all-black cast, took in about $201.8 million domestically when it opened over the four-day Presidents’ Day weekend this year, the fifth-biggest opening of all time.

Many other film properties are in development, in addition to sequels in established franchises. Characters Mr. Lee had a hand in creating now enjoy a degree of cultural penetration they have never had before.

Mr. Lee wrote a slim memoir, “Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee,” with George Mair, published in 2002. His 2015 book, “Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir” (written with Peter David and illustrated in comic-book form by Colleen Doran), pays abundant credit to the artists many fans believed he had shortchanged years before.

Recent Marvel films and TV shows have also often credited Mr. Lee’s former collaborators; Mr. Lee himself has almost always received an executive producer credit. His cameo appearances in them became something of a tradition. (Even “Teen Titans Go! to the Movies,” an animated feature in 2018 about a DC superteam, had more than one Lee cameo.) TV shows bearing his name or presence have included the reality series “Stan Lee’s Superhumans” and the competition show “Who Wants to Be a Superhero?”

Mr. Lee’s unwavering energy suggested that he possessed superpowers himself. (In his 90s he had a Twitter account, @TheRealStanlee.) And the National Endowment for the Arts acknowledged as much when it awarded him a National Medal of Arts in 2008. But he was frustrated, like all humans, by mortality.

“I want to do more movies, I want to do more television, more DVDs, more multi-sodes, I want to do more lecturing, I want to do more of everything I’m doing,” he said in “With Great Power …: The Stan Lee Story,” a 2010 television documentary. “The only problem is time. I just wish there were more time.”

No comments:

Post a Comment