Frank Black

11 July 2017

Thanks to his work with Val Lewton in the 1950s and that late gem, Night of the Demon (1957), Jacques Tourneur will be forever associated with the horror genre, but a considered look at his career will see that this supreme stylist made films in many genres, including one of the greatest film noirs, Out of the Past (1947).

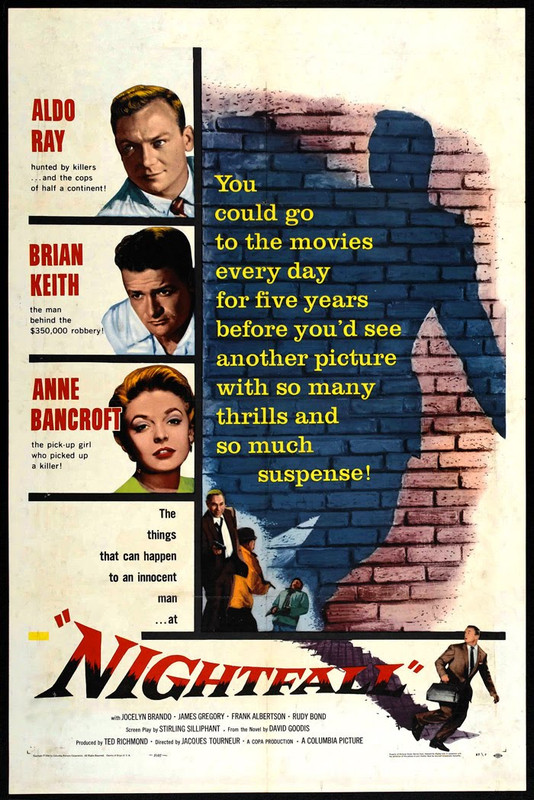

Nightfall is a smart little crime drama, tightly-scripted by Stirling Silliphant and based on a novel by David Goodis, who wrote several noirish thrillers that were adapted into movies, including Down There, filmed by Francois Truffaut as Shoot the Piano Player (1960), Delmer Daves’ Dark Passage (1946) and The Burglar, directed by Paul Wendkos (1957).

Like Out of the Past, an event from the protagonist’s history comes to determine his life in the present and flashbacks play a key role; however, unlike Out of the Past’s one flashback section, the narrative in Nightfall is punctuated by a series of flashbacks that explain the origin of the events until past meets present in snowy Wyoming and the story is violently resolved.

Tourneur presents the audience with an enigma from the outset. A young man, Art Rayburn (Aldo Rey), who has taken the name Jim Vanning, wanders through a newsstand, checking out newspapers from across the United States. He asks for one from Evanston, Illinois, but it’s the only one they don’t have, symbolising that this is a man out of place. To underline this, when the lights flicker on, Vanning, shot from behind, reacts with a nervous jump, as if someone is after him. Who is this man and why does he act this way?

Leaving the brightness of the shop, he is filmed in long shot from across the street, bathed in classic Tourneur chiaroscuro, implying guilt or trouble - or perhaps someone about to emerge from the darkness of his past. He looks over his shoulder as if he fears he’s being followed – and it seems he is. Crossing into the shot is Ben Fraser (James Gregory), who we later discover is an insurance investigator, and he walks up to Vanning and makes small talk before catching a bus home.

The nature of the suspected crime isn’t revealed at first, but throughout the film, Fraser seems to doubt Vanning’s guilt, expressing this to his wife, Laura (Jocelyn Brando), and on several occasions Tourneur uses editing to hint at a bond between them; for example, after Laura goes to make Fraser a drink, there’s a cut to coffee being poured at Vanning’s table.

Thanks to his work with Val Lewton in the 1950s and that late gem, Night of the Demon (1957), Jacques Tourneur will be forever associated with the horror genre, but a considered look at his career will see that this supreme stylist made films in many genres, including one of the greatest film noirs, Out of the Past (1947).

Nightfall is a smart little crime drama, tightly-scripted by Stirling Silliphant and based on a novel by David Goodis, who wrote several noirish thrillers that were adapted into movies, including Down There, filmed by Francois Truffaut as Shoot the Piano Player (1960), Delmer Daves’ Dark Passage (1946) and The Burglar, directed by Paul Wendkos (1957).

Like Out of the Past, an event from the protagonist’s history comes to determine his life in the present and flashbacks play a key role; however, unlike Out of the Past’s one flashback section, the narrative in Nightfall is punctuated by a series of flashbacks that explain the origin of the events until past meets present in snowy Wyoming and the story is violently resolved.

Tourneur presents the audience with an enigma from the outset. A young man, Art Rayburn (Aldo Rey), who has taken the name Jim Vanning, wanders through a newsstand, checking out newspapers from across the United States. He asks for one from Evanston, Illinois, but it’s the only one they don’t have, symbolising that this is a man out of place. To underline this, when the lights flicker on, Vanning, shot from behind, reacts with a nervous jump, as if someone is after him. Who is this man and why does he act this way?

Leaving the brightness of the shop, he is filmed in long shot from across the street, bathed in classic Tourneur chiaroscuro, implying guilt or trouble - or perhaps someone about to emerge from the darkness of his past. He looks over his shoulder as if he fears he’s being followed – and it seems he is. Crossing into the shot is Ben Fraser (James Gregory), who we later discover is an insurance investigator, and he walks up to Vanning and makes small talk before catching a bus home.

The nature of the suspected crime isn’t revealed at first, but throughout the film, Fraser seems to doubt Vanning’s guilt, expressing this to his wife, Laura (Jocelyn Brando), and on several occasions Tourneur uses editing to hint at a bond between them; for example, after Laura goes to make Fraser a drink, there’s a cut to coffee being poured at Vanning’s table.

The narrative emphasises the role of chance and coincidence, which play on Vanning’s paranoia. In a bar, he meets a young model, Marie (Anne Bancroft) and it seems like she’s hitting on him and wants the loan of some money to pay her bill; of course, in keeping with generic norms, they hit it off. Leaving the bar, he’s jumped by the two killers who’ve been tracking him and they order her to go away. It seems like the classic noir femme fatale set-up, but it becomes apparent that it wasn’t intentional: there was no set-up and she really did need the money to pay her for her drink. He pointedly tells her, “… you were unlucky enough to talk to me tonight.”

The foregrounding of coincidence continues throughout the film; indeed Vanning’s initial involvement with the killers is purely down to unconscious chance as revealed in one of the flashbacks set in the snow-covered wilds of Wyoming where a hunting trip with his friend, Doc Gurston (Frank Albertson), is interrupted by an accident when a car swerves off an icy road.

Gurston and Vanning rush to help, but the crash victims turn out to be bank robbers, the subdued, almost eerily pleasant John (Brian Keith) and the borderline psychotic Red (Rudy Bond), prefiguring the kind of relationship between killers that feature in Quentin Tarantino's work. Gurston fixes John’s arm and then is shot by Red, who also shoots Vanning and leaves him for dead. He’s alive, of course, and on waking, he finds the robbers have taken Gurston’s bag instead of the one filled with cash. Vanning escapes, by now with John and Red in pursuit, and he leaves the bag hidden before running off and creating a new life for himself, all the time in the knowledge that he has gone from being the hunter to the prey.

Tourneur’s cinematographer was Burnett Guffey, an Oscar-winner for his work on Fred Zinneman’s From Here to Eterntity (1953) and, later, for Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), but also well-versed in noir over a series of films that included Nicholas Ray’s masterpiece, In a Lonely Place (1950). He makes stunning use of the stark, dazzling landscape of the snowy Wyoming hills juxtaposed with the moody blacks and greys of the scenes in the present, particularly during the sequence when the killers take Vanning to an oilfield at dusk to extract information.

The claustrophobic and threatening environment of the constantly moving predatory derricks contrasts with the flashbacks of the clean, natural white open spaces of Wyoming, while the editing helps create tension for the audience, prolonging Vanning’s captivity. As the flashbacks reveal more, the stark whiteness becomes sullied with the presence of John and Red. Of course, Wyoming looks clean because of the snow, but it’s the snow that later hides the reason behind the killers’ pursuit of Vanning: the dirty money stolen in the bank-job.

It’s also in Wyoming that things finally come to a head. Escaping the city with Marie, Vanning takes a bus to locate the money, unaware that the diligent Fraser is only a few seats behind them. Finally, he approaches Vanning while he waits outside a church for Marie. The mise-en-scène positions Vanning as an outsider and with his back towards the camera, the shot echoing the earlier one where he flinches when the lights come on at the newsagents just before Fraser enters his life; the presence of the church, however, hints at confession and redemption. The scene is carried by Rey and Gregory’s easy-going, naturalistic style as Vanning opens up to Fraser and confirms the latter’s suspicion that he has been innocent all along.

After Red shot Doc Gurston, he forced Vanning to pick up the gun that killed him. By chance, Red fails to kill Vanning but his fingerprints were now on the rifle and – another coincidence - unbeknownst to the killers, Gurston’s wife had sent Vanning unrequited love letters, so he became a suspect for the murder as well as the robbery.

Coincidence rears its head again when Vanning, Fraser and Marie go to locate the money in the melting Wyoming snow. They approach a shack seemingly in the middle of nowhere and as Vanning walks around it, the angle of the camera reveals John and Red, the contrast in their manner engendering further anxiety, but they squabble and John’s low key approach is his downfall as Red shoots him dead in the same cold-hearted manner as he killed Gurston. Vanning launches himself towards John’s gun and a fight ensues on board a snow plough. While the will it/won’t it suspense of whether or not it will demolish the shack where Fraser and Marie are tied up conjures up the Perils of Pauline, real tension is created by Tourneur’s use of close-ups of Red and Vanning as they tussle in the plough’s cabin and when the former is pushed out, the use of the point of view shot as the blades come whirling closer to Red underlines his own stark brutality – and perhaps gave the Coen Brothers something to allude to when they made Fargo almost forty years later.

If you can ignore the awful theme tune crooned by Duke Ellington alumnus Al Hibbler, this is a rewarding late period noir, with an engaging, twisted plot, superbly handled by a master of mood and suspense and well-acted by a cast of fairly minor players.

* Okay, maybe more like once in a blue moon...

Gurston and Vanning rush to help, but the crash victims turn out to be bank robbers, the subdued, almost eerily pleasant John (Brian Keith) and the borderline psychotic Red (Rudy Bond), prefiguring the kind of relationship between killers that feature in Quentin Tarantino's work. Gurston fixes John’s arm and then is shot by Red, who also shoots Vanning and leaves him for dead. He’s alive, of course, and on waking, he finds the robbers have taken Gurston’s bag instead of the one filled with cash. Vanning escapes, by now with John and Red in pursuit, and he leaves the bag hidden before running off and creating a new life for himself, all the time in the knowledge that he has gone from being the hunter to the prey.

Tourneur’s cinematographer was Burnett Guffey, an Oscar-winner for his work on Fred Zinneman’s From Here to Eterntity (1953) and, later, for Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), but also well-versed in noir over a series of films that included Nicholas Ray’s masterpiece, In a Lonely Place (1950). He makes stunning use of the stark, dazzling landscape of the snowy Wyoming hills juxtaposed with the moody blacks and greys of the scenes in the present, particularly during the sequence when the killers take Vanning to an oilfield at dusk to extract information.

The claustrophobic and threatening environment of the constantly moving predatory derricks contrasts with the flashbacks of the clean, natural white open spaces of Wyoming, while the editing helps create tension for the audience, prolonging Vanning’s captivity. As the flashbacks reveal more, the stark whiteness becomes sullied with the presence of John and Red. Of course, Wyoming looks clean because of the snow, but it’s the snow that later hides the reason behind the killers’ pursuit of Vanning: the dirty money stolen in the bank-job.

It’s also in Wyoming that things finally come to a head. Escaping the city with Marie, Vanning takes a bus to locate the money, unaware that the diligent Fraser is only a few seats behind them. Finally, he approaches Vanning while he waits outside a church for Marie. The mise-en-scène positions Vanning as an outsider and with his back towards the camera, the shot echoing the earlier one where he flinches when the lights come on at the newsagents just before Fraser enters his life; the presence of the church, however, hints at confession and redemption. The scene is carried by Rey and Gregory’s easy-going, naturalistic style as Vanning opens up to Fraser and confirms the latter’s suspicion that he has been innocent all along.

After Red shot Doc Gurston, he forced Vanning to pick up the gun that killed him. By chance, Red fails to kill Vanning but his fingerprints were now on the rifle and – another coincidence - unbeknownst to the killers, Gurston’s wife had sent Vanning unrequited love letters, so he became a suspect for the murder as well as the robbery.

Coincidence rears its head again when Vanning, Fraser and Marie go to locate the money in the melting Wyoming snow. They approach a shack seemingly in the middle of nowhere and as Vanning walks around it, the angle of the camera reveals John and Red, the contrast in their manner engendering further anxiety, but they squabble and John’s low key approach is his downfall as Red shoots him dead in the same cold-hearted manner as he killed Gurston. Vanning launches himself towards John’s gun and a fight ensues on board a snow plough. While the will it/won’t it suspense of whether or not it will demolish the shack where Fraser and Marie are tied up conjures up the Perils of Pauline, real tension is created by Tourneur’s use of close-ups of Red and Vanning as they tussle in the plough’s cabin and when the former is pushed out, the use of the point of view shot as the blades come whirling closer to Red underlines his own stark brutality – and perhaps gave the Coen Brothers something to allude to when they made Fargo almost forty years later.

If you can ignore the awful theme tune crooned by Duke Ellington alumnus Al Hibbler, this is a rewarding late period noir, with an engaging, twisted plot, superbly handled by a master of mood and suspense and well-acted by a cast of fairly minor players.

* Okay, maybe more like once in a blue moon...

No comments:

Post a Comment