Barbican, London

The first UK retrospective of American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), a powerful woman of unparalleled vigour and resilience. Using her camera as a political tool to shine a light on cruel injustices, Lange went on to become a founding figure of documentary photography.

Sean O'Hagan

Lange’s meticulous approach and compositional skill are evident throughout this exhaustive show, matched by her seemingly instinctive ability to home in on people whose faces, gestures and silhouettes are emblematic of the economic and political forces shaping their lives. If the Great Depression was the defining event of her creative life, and the images she made on the streets of the US in the 1930s remain her most celebrated work, this chronological exhibition traces the arc of a much longer creative journey that spanned the ensuing decades until her death in 1965.

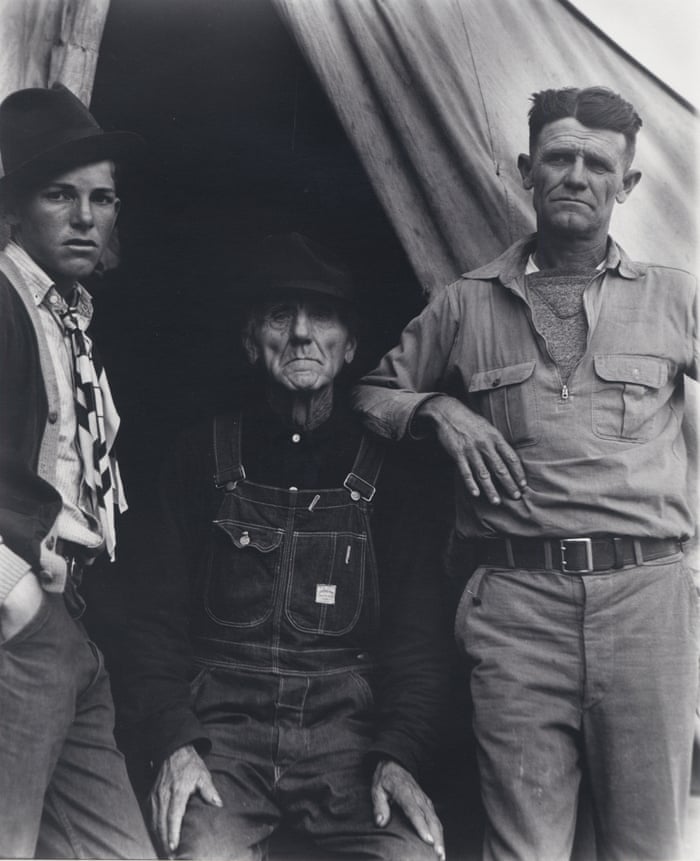

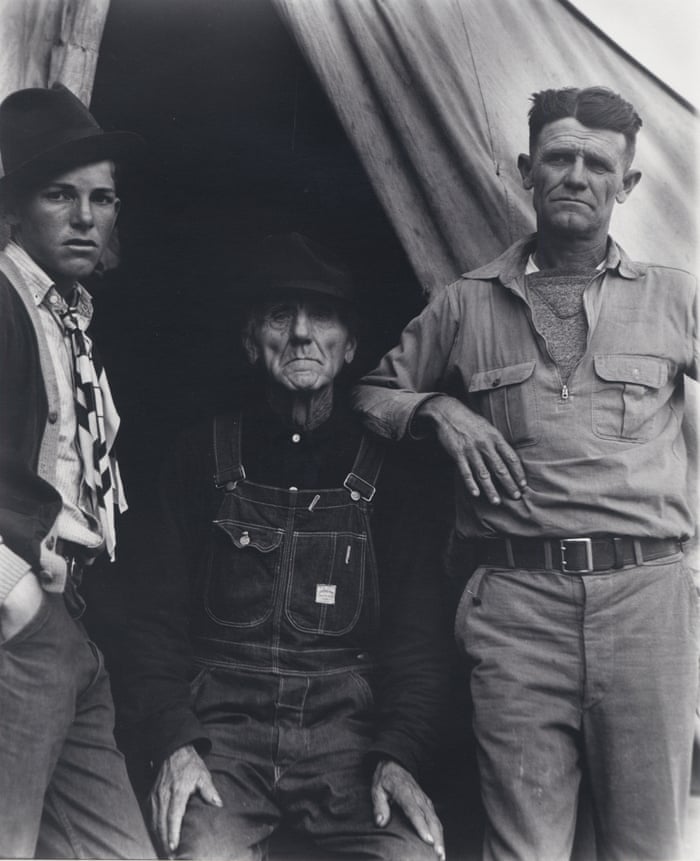

Three Generations of Texans, now Drought Refugees (c1935). Photograph: Courtesy of Scott Nichols Gallery, San Francisco © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Three Generations of Texans, now Drought Refugees (c1935). Photograph: Courtesy of Scott Nichols Gallery, San Francisco © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

There are 15 series of works on display, from Lange’s early studio portraits of friends and fellow artists to the photographs she made of the west of Ireland and its people in the mid-1950s. The Great Depression, she said, “woke me up”, and her political awakening was matched by a creative shift towards more expressive portraiture.

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, 1933. The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, 1933. The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Her less familiar studies of the poor and dispossessed often evince a melancholy beauty: a young female migrant worker, a makeshift cotton scarf shielding her face from the sun, gazes stoically at the camera as if surrendering to it. An older woman is caught from below, gaunt and erect in stained labourer’s clothes, against an unforgiving sky. Often, Lange’s images manage to be both intimate and epic, the sense of individual isolation she captures evoking the collective experience of countless migrant workers, uprooted from their homes and forced to work long hours for pitiful wages in the promised land of the American west. For me, this ability to distill the plight of vast numbers of people into a single image is Lange’s defining gift as an image-maker.

Centerville, California, 1942. This evacuee stands by her baggage as she waits for an evacuation bus. The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Centerville, California, 1942. This evacuee stands by her baggage as she waits for an evacuation bus. The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

One of her series, Japanese American Internment, has an added resonance given what is happening to migrant parents and children in the US right now. Made in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, it documents the fate of the 120,000 US citizens with Japanese ancestry who were rounded up and relocated to makeshift prison camps for the duration of the war. Though hired by the War Location Authority, there is nothing neutral about Lange’s gaze, which explains why most of the photographs remained unseen for decades. “They wanted a record,” she said, “but not a public record.”

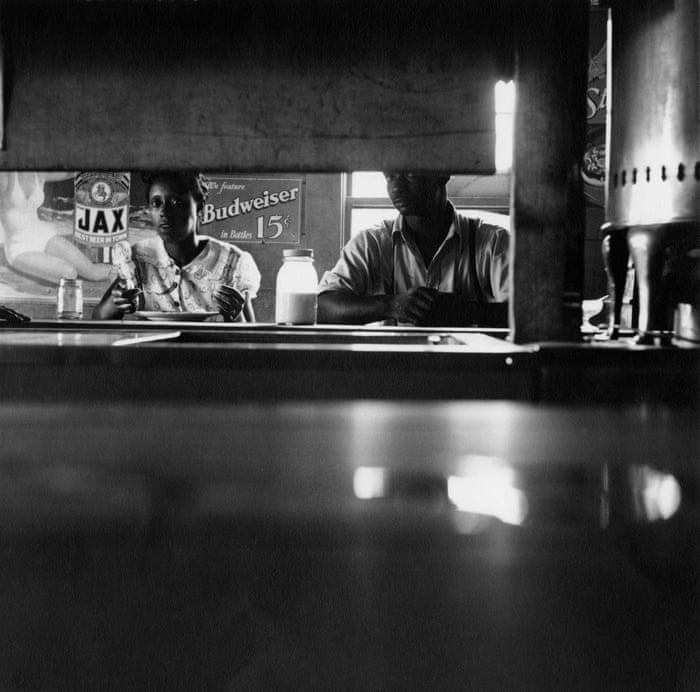

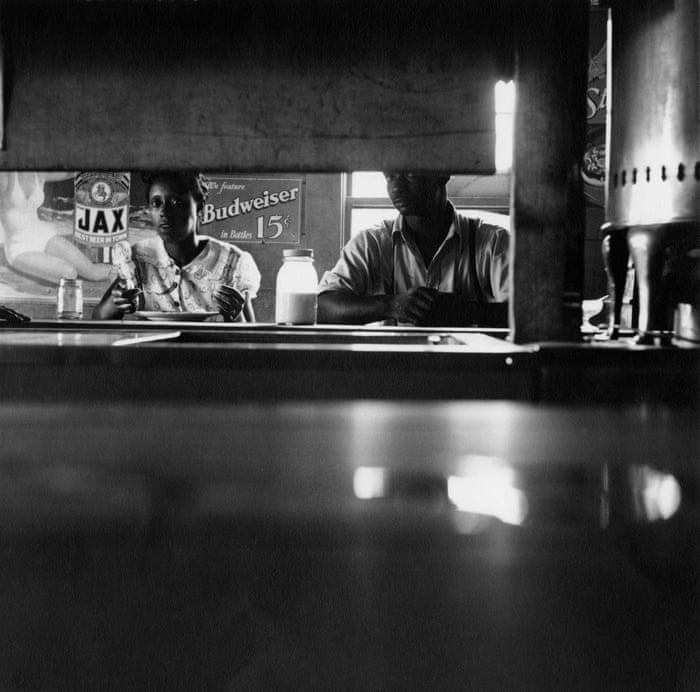

Restaurant Segregation, Mississippi, 1938. The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Restaurant Segregation, Mississippi, 1938. The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Lange remained a socially engaged photographer throughout her life, never quite reinventing herself in the restlessly creative way her contemporary Walker Evans did. Nevertheless, her gaze deepened and took on a more evocative aspect as she engaged with an everyday US defined by stark contradictions and casual injustices. Her Deep South series possesses a palpable, even poetic, sense of place, with certain images evincing an almost languorous feel even as they portray a society where segregation and exploitation have become institutionalised, and thus normalised. A 1936 group portrait entitled Plantation Overseer and His Field Hands, near Clarksdale, Mississippi, is a carefully composed tableau that implicitly portrays the deeply embedded racist power structures of the American south.

At one point, Lange, like Evans, became fascinated by the vernacular architecture of the south, the timber churches, silos and shopfronts, which she shot with uncharacteristic detachment. Simultaneously, she began cropping her portraits to isolate hands, torsos and the texture of fabric and material worn and frayed by toil. The curators make a tenuous connection between the geometry of these arresting closeups and the childhood polio that left Lange lame, but they seem more indicative of her determination to transcend the traditional documentary work that had defined her. Caught on film, in old age, she speaks with extraordinary insight about her work and photography in general, which she defines as “a peculiar and powerful instrument for saying to the world: this is how it is”. Politics of Seeing is a monumental, sometimes surprising, retrospective that traces the full arc of Lange’s sustained creative life. For anyone even remotely interested in the history of photography, it is a must-see show.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is at the Barbican, London, from 22 June to 2 September.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/jun/20/dorothea-lange-vanessa-winship-review-barbican-london

Sean O'Hagan

The Guardian

Wed 20 Jun 2018

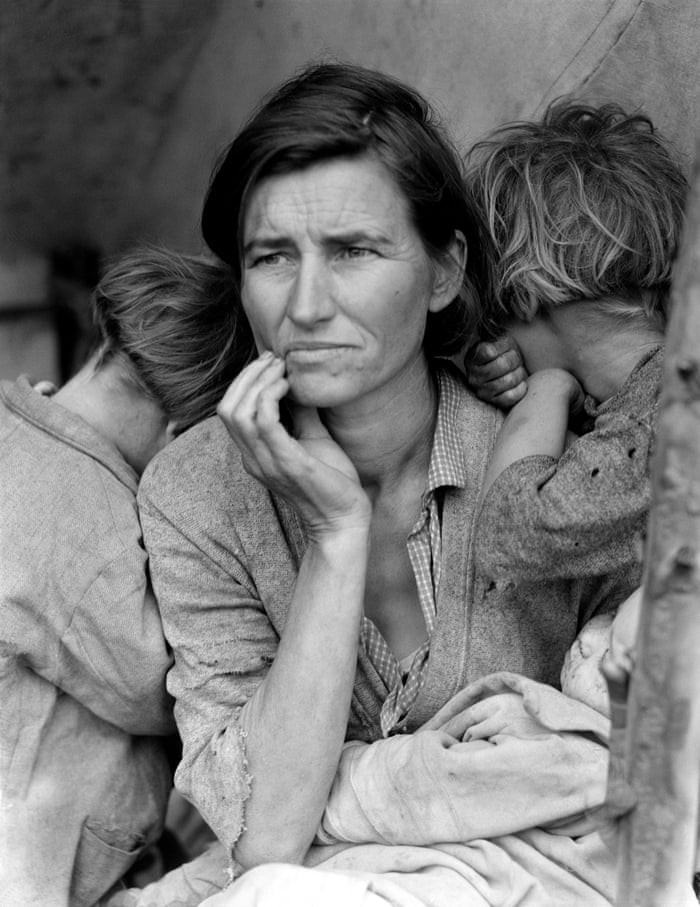

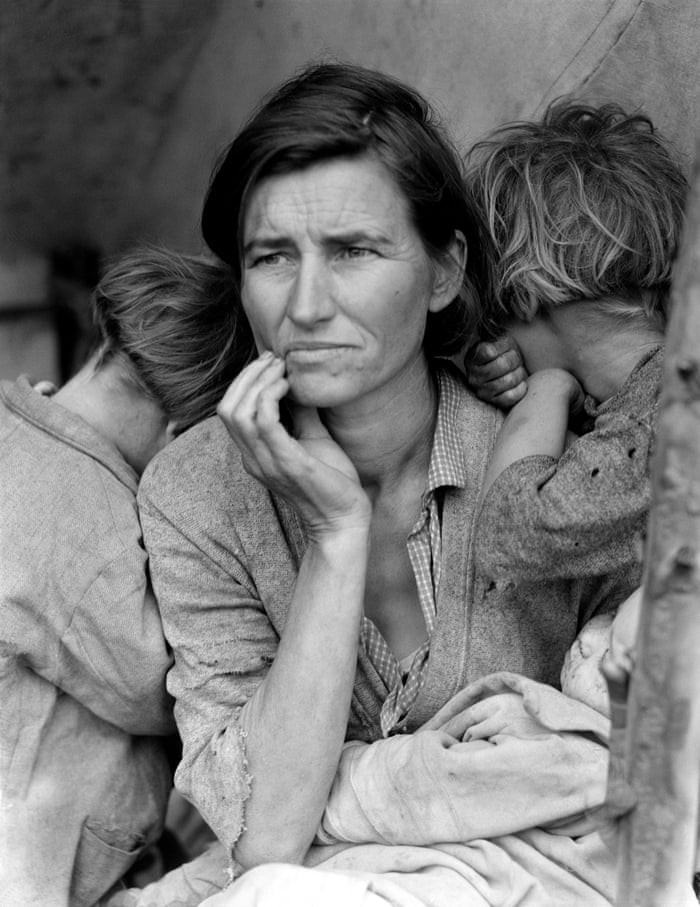

“The camera,” Dorothea Lange once said, “is an instrument that teaches people to see without a camera.” Her portrait of Florence Owens Thompson, now universally known as Migrant Mother, provided powerful evidence that this was indeed the case. Taken in a camp for destitute migrant workers in California in 1936, while Lange was documenting the plight of the dispossessed during the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the portrait is a study of a mother’s anxiety. When it was published in the press, it precipitated a generous flow of government aid to the Californian work camps.

“The camera,” Dorothea Lange once said, “is an instrument that teaches people to see without a camera.” Her portrait of Florence Owens Thompson, now universally known as Migrant Mother, provided powerful evidence that this was indeed the case. Taken in a camp for destitute migrant workers in California in 1936, while Lange was documenting the plight of the dispossessed during the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the portrait is a study of a mother’s anxiety. When it was published in the press, it precipitated a generous flow of government aid to the Californian work camps.

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936). The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Migrant Mother has become perhaps the most famous American photograph of the past century. It haunted Thompson, who later tried to prevent its reproduction and, in 1978, told a journalist: “I wish she had never taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. She didn’t ask my name.” Ironically, Lange had been instructed to ensure the anonymity of her subjects in guidelines laid down by the FSA. The portrait is given a room of its own in this extensive retrospective, with five alternative versions on display, including one of the few surviving early prints in which Thompson’s thumb is visible in the bottom-right corner, clasping a tent pole. For some reason, the thumb bothered Lange so much that she rendered it as a blurred presence in later prints.

A family walking on a highway with their five children from Idabel to Krebs in Oklahoma, June 1938. Photograph: The Dorothea Lange Collection/Oakland Museum of California

Lange’s meticulous approach and compositional skill are evident throughout this exhaustive show, matched by her seemingly instinctive ability to home in on people whose faces, gestures and silhouettes are emblematic of the economic and political forces shaping their lives. If the Great Depression was the defining event of her creative life, and the images she made on the streets of the US in the 1930s remain her most celebrated work, this chronological exhibition traces the arc of a much longer creative journey that spanned the ensuing decades until her death in 1965.

There are 15 series of works on display, from Lange’s early studio portraits of friends and fellow artists to the photographs she made of the west of Ireland and its people in the mid-1950s. The Great Depression, she said, “woke me up”, and her political awakening was matched by a creative shift towards more expressive portraiture.

Her less familiar studies of the poor and dispossessed often evince a melancholy beauty: a young female migrant worker, a makeshift cotton scarf shielding her face from the sun, gazes stoically at the camera as if surrendering to it. An older woman is caught from below, gaunt and erect in stained labourer’s clothes, against an unforgiving sky. Often, Lange’s images manage to be both intimate and epic, the sense of individual isolation she captures evoking the collective experience of countless migrant workers, uprooted from their homes and forced to work long hours for pitiful wages in the promised land of the American west. For me, this ability to distill the plight of vast numbers of people into a single image is Lange’s defining gift as an image-maker.

One of her series, Japanese American Internment, has an added resonance given what is happening to migrant parents and children in the US right now. Made in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, it documents the fate of the 120,000 US citizens with Japanese ancestry who were rounded up and relocated to makeshift prison camps for the duration of the war. Though hired by the War Location Authority, there is nothing neutral about Lange’s gaze, which explains why most of the photographs remained unseen for decades. “They wanted a record,” she said, “but not a public record.”

Lange remained a socially engaged photographer throughout her life, never quite reinventing herself in the restlessly creative way her contemporary Walker Evans did. Nevertheless, her gaze deepened and took on a more evocative aspect as she engaged with an everyday US defined by stark contradictions and casual injustices. Her Deep South series possesses a palpable, even poetic, sense of place, with certain images evincing an almost languorous feel even as they portray a society where segregation and exploitation have become institutionalised, and thus normalised. A 1936 group portrait entitled Plantation Overseer and His Field Hands, near Clarksdale, Mississippi, is a carefully composed tableau that implicitly portrays the deeply embedded racist power structures of the American south.

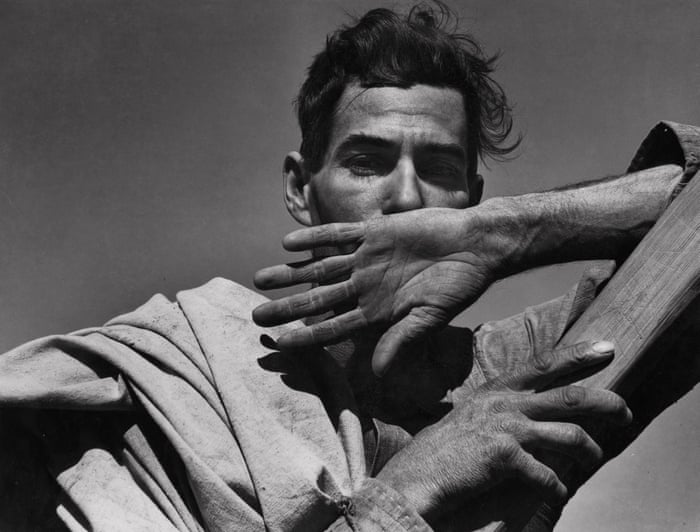

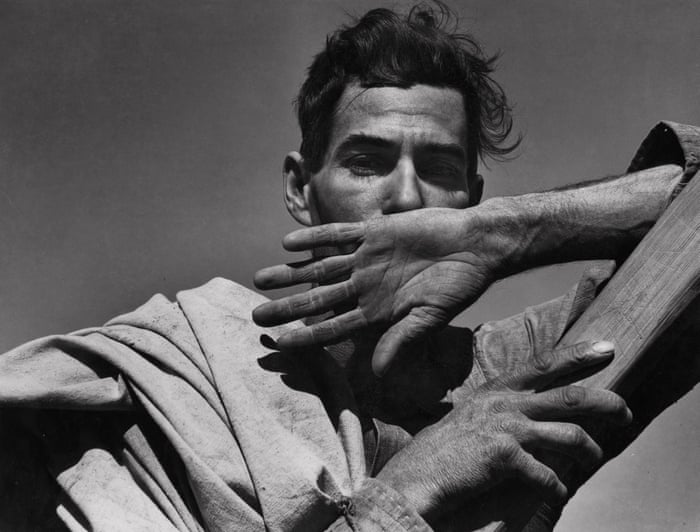

Dorothea Lange’s image of a migratory cotton picker, Eloy, in Arizona, 1940. Photograph: The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

At one point, Lange, like Evans, became fascinated by the vernacular architecture of the south, the timber churches, silos and shopfronts, which she shot with uncharacteristic detachment. Simultaneously, she began cropping her portraits to isolate hands, torsos and the texture of fabric and material worn and frayed by toil. The curators make a tenuous connection between the geometry of these arresting closeups and the childhood polio that left Lange lame, but they seem more indicative of her determination to transcend the traditional documentary work that had defined her. Caught on film, in old age, she speaks with extraordinary insight about her work and photography in general, which she defines as “a peculiar and powerful instrument for saying to the world: this is how it is”. Politics of Seeing is a monumental, sometimes surprising, retrospective that traces the full arc of Lange’s sustained creative life. For anyone even remotely interested in the history of photography, it is a must-see show.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is at the Barbican, London, from 22 June to 2 September.

No comments:

Post a Comment