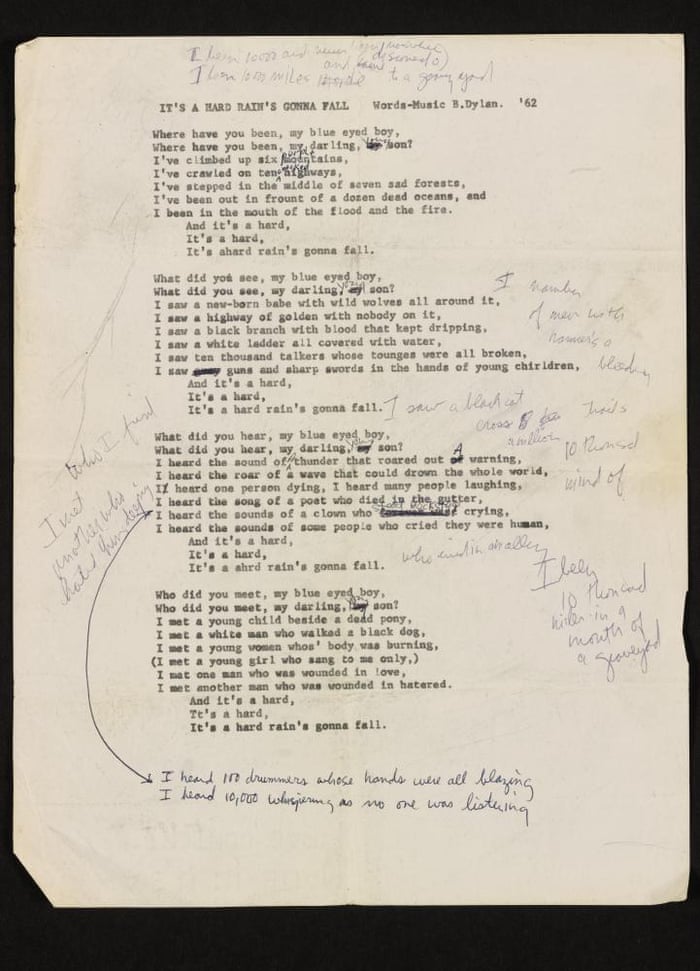

Velazquez’s masterpiece Las Meninas may be the first postmodern painting. But what is its secret? Does it have one?

Ever since The Da Vinci Code (2003), art pundits and novelists have been queuing up to reveal the “secrets” of painters and paintings. Everything is Happening: Journey into a Painting, by the late Michael Jacobs, is one of the more quixotic examples. But Dan Brown didn’t set this particular occult ball rolling, and for at least 200 years art experts and amateurs have been sleuthing around the old masters.

Painting is fertile ground for such speculations. At least since classical antiquity, it has been judged more mysterious (or vacuous) than verbal expression. So in the days when poetry was read aloud or sung, painting was known as “dumb poetry”. A painting can’t introduce itself (“Ciao, mi chiamo Mona Lisa!”) or say what it is thinking (“È finito, Leonardo?”) whereas hundreds of articulate people introduce themselves to Dante in the Divine Comedy. We only know she is Mona Lisa, painted at snail’s pace by Leonardo, from written sources – above all, Vasari’s description. So with pictures, there can be basic levels of enigma and estrangement related to identification, attribution and expression.

After the rise of art academies in the 18th century, other forms of mysteriousness were found; and these mysteries were problems to be solved. Academies had a rationalist approach to art-making, and every artist had to be rigorously trained using a standardised curriculum. The great art of the past had to be repeated; academies couldn’t tolerate the idea that greatness was indefinable and ineffable, its essence explained away by the vague blase term “je ne sais quoi” – as in: “Titian’s skies have a certain je ne sais quoi.”

Academic rationalism gave rise to the belief that the less orthodox old masters must have had a secret ingredient to create those now inimitable effects. In 1795,James Gillray made a satirical cartoon entitled Titianus Redivivus (Titian Resurrected) about the so-called Venetian Secret, a forged manual of Venetian painting whose “secrets” were sold to several Royal Academicians by a miniaturist painter, Ann Jemima Provis. David Hockney’s pharaonic Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters (2001) was following in Provis’s footsteps.

Romantics have countered the rationalists by devising truly inexplicable types of mysteriousness. A classic example is Balzac’s short story “The Unknown Masterpiece” (1845), set in Paris in 1612. The young Nicolas Poussin (future darling of French academic painters), is taken by his teacher to see the old genius Frenhofer. He is a “supernatural” figure who “alone possessed the secret of giving life to his figures”. Frenhofer warns the youngster: “You may know your syntax thoroughly and make no blunders in your grammar, but it takes that and something more to make a great poet.” He has no students, so his “secret” will be lost with him – and Balzac doesn’t let on. Frenhofer has been working for 10 years on a mysterious picture of a beautiful courtesan, which Poussin and his master are privileged to see. Initially, all they can discern is “a dead wall of paint”, but on closer inspection “they distinguished a bare foot emerging from the chaos of colour, half-tints and vague shadows that made up a dim, formless fog. Its living delicate beauty held them spellbound.” But Poussin insists there is nothing on the canvas at all, and drives Frenhofer to despair. He burns his paintings, then dies.

Balzac insists both on the essential unfathomability of great art and artists, and on the rarity and incompleteness of masterpieces: truth and beauty only lie in tantalising fragmentary details, conceived and perceived in a state of mystical rapture. Since Balzac’s day, two art details in particular have held us both spellbound and mystified: the smiling corner of Mona Lisa’s mouth, and the glinting mirror in Velázquez’s great group portrait Las Meninas (1656). The distinguished travel writer Jacobs, in his incomplete and probably incompletable memoir-cum-homage, is “a detective reopening an investigation into an unresolved mystery”. Las Meninas is “less an object than a living entity endowed with the secret of eternal life”. The composition’s “exact mathematics” may “harbour secret codes”, and there is “a hint of wondrous worlds lying beyond the mirror and the open door beside it”. The Hispanophile Jacobs is part mystic, part spy. But we are never party to these “wondrous worlds”: they remain undiscovered countries.

Velázquez’s most magnificent court portrait is an unlikely candidate for mega-mystery status. It is far from being “dumb poetry”. We know a vast amount about it from contemporary published sources – the names of all but one of the 11 protagonists, and the actual room in the royal palace in which it is located. The five-year-old Infanta Margaret Theresa and her entourage, including ladies in waiting, dwarves and a big dog, are on a studio visit. The king and queen of Spain are reflected in the mirror on the back wall, so they must presumably be standing in front, the “sitters” for the portrait that Velázquez is painting; perhaps they have just come in. Velázquez and the Infanta look at them. We know that members of court came to watch the painter as he worked on it in 1656, so they may conceivably have gathered like this in his studio. The man in the doorway was chamberlain of the queen’s quarters, required to open doors for the royals, so he’s doing his job. The picture was first displayed in the king’s private office where few were admitted, and each day he could stand before it and see himself reflected in the mirror. Palace inventories have even allowed us to identify the pictures, swathed in shadow, that line the walls – copies of paintings by Rubens of art-related subjects taken from Ovid.

The most fanciful thing about the picture is making the king and queen stand while their portrait is painted. A study for Velázquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X in the Wellington museum, Apsley House, shows that the artist, like most portrait painters, only made quick sketch studies of the head from life. Velázquez also never painted a massive double portrait, of the kind that Van Dyck made for Charles I and Queen Henrietta. Indeed, the sprawling extravaganza of Las Meninas is his most Van Dyckian portrait, and after Velázquez’s death in 1660, Van Dyck’s portrait style would eclipse his own at court.

With the opening of the Prado in 1819, and the looting and sale of paintings during and after the Napoleonic wars, Spanish art would become all the rage in Europe and America. The previously unknown Velázquez was lionised by artists such as Courbet, Manet and Whistler. Ruskin called him “the most accurate portrait painter of Spain”. The feminising title, Las Meninas, was first used in the Prado catalogue of 1843, and it was hailed as a masterpiece of backstairs realism. It was compared to that new invention photography, and the splotchy technique was later seen as a forerunner of impressionism. There was magic in Velázquez’s methods – but there was also magic in photography. A mesmerised Théophile Gautier asked: “Where, then, is the picture?”

It was in the 20th century, when Las Meninas was displayed in a special room in the Prado with a flanking mirror so visitors could see themselves and the picture, that it suddenly became as haunted and labyrinthine as any expressionist film set (and it even had dwarves). Another defining moment came when Michel Foucault discussed the picture in the opening chapter of The Order of Things(1966). Although he described it in pedantic “realist” detail, he effectively saw it as the first postmodern picture. Whereas all earlier art was an art of representation of the material world, Las Meninas was a representation of a representation: its main royal protagonists were simultaneously present and absent, only glimpsed blurrily – and in miniature – in the mirror. Foucault clearly saw Velázquez as a precursor of Magritte, about whom he wrote in 1968. Carlos Fuentes’s general study of Hispanic culture, The Buried Mirror (1992), argued that the mirror embodied the spirit of Spain – a “reflection of reality and a projection of the imagination”.

Jacobs’s book was left half- finished at his death. His journalist friend and amanuensis Ed Vulliamy has provided a succinct introduction to the painting, and an obituary-style afterword. One suspects that had Jacobs lived, it would have always remained a Frenhofer-style work-in-progress, with shards of insight emerging from a colourful autobiographical fog. His narrative begins with the unexpected arrival through the post of a jigsaw puzzle of the picture, which encourages him to head deeper “into an ever-expanding labyrinth”. This encompasses restless detours into the “sunless” world of research libraries; meditations on the spying scandal that engulfed his art history teacher Anthony Blunt; and the picture’s hair-raising peregrinations during the Spanish civil war (which prompts thoughts about whether saving art is more important than saving people). At times, Jacobs’s speculations owe less to Professor Blunt than to Professor Robert Langdon: “Simultaneously I scribbled down random observations of possible bearing on the case: my sharing of a birthday with Foucault, Foucault’s death at the same age that Velázquez had begun the painting, the realisation that the word ‘meaning’ was nearly an anagram of Meninas.” Another near anagram is “insane”.

So just what is the famous mirror up to? We know that Velázquez owned 10 mirrors, many measuring instruments, as well as treatises on perspective and optics. So he was fascinated by art theory and by reflections and illusions. Here, he presents himself as a master of perspective and lighting effects, but also as a witty entertainer who aligns himself with court dwarves and jesters (jesters turned the world upside down; Velázquez shows it back to front). It’s a portrait of the Infanta (the only surviving royal child), but also a manifesto of the illusionistic miracles that painting can achieve. In ancient Rome, mirrors’ plates were sometimes made from polished silver, and it’s quite possible that this mirror – with its glinting silvery edge – is made from solid South American silver, which had flooded into Spain from its colonies. Its blurriness is similar to that of the mirror held up by Cupid in Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus: just as we only see God “through a glass, darkly”, rather than “face to face”, Velázquez only gives us a tantalising hazy glimpse of these mortal gods and goddesses. Early on in his study, Jacobs quotes and demurs from the saying: “The greatest secret is that there is no secret.” In Velázquez’s case, there are no real secrets, just sublime reticence and suggestiveness.

Michael Jacobs, Velázquez and me

When the writer Michael Jacobs found he was dying, he asked his friend Ed Vulliamy to complete his last book, a personal meditation on Velázquez’s masterpiece Las Meninas. Ed Vulliamy kept his promise. Here he recalls his friend’s humour, passion and indomitable spirit as they worked on it together

Ed Vulliamy

Sunday 26 July 2015

In the winter months of early 2014, Jackie Rae – widow of a man I had come to know for a painfully brief period of time – sent me the manuscript of a book on which her husband – the wonderful Michael Jacobs, Hispanist, travel writer and art historian – had been working when he died.

It was to have been Michael’s magnum opus: an attempt to unlock the secrets of the painting he considered the greatest work of the artist he esteemed above all others: Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez. It was also to be a reflection on the study and fruitful enjoyment of painting. Michael was a writer who defied genre: at the Courtauld Institute he had been a star student of its director, the art historian and keeper of the Queen’s pictures Anthony Blunt (to whom Michael remained fiercely loyal after Blunt was exposed in 1979 as a spy for Soviet intelligence). Michael’s book was to have been about that too.

Michael was at work on the manuscript when he went, in late September 2013, for examination of what he thought was lumbago. He was instead diagnosed with aggressive renal cancer. The initial prognosis of three to five years to live led Michael to believe he would be able to complete the volume. In the event, the cancer corroded his body with merciless speed and Michael was dead within three and a half months, passing away at St Bartholomew’s hospital, London, on 11 January 2014.

So what Jackie sent to me that winter was the masterpiece Michael left unfinished, and which – as death assailed him – he had asked me to complete. This I tried to do on the basis of conversations with a dying friend, right up until 36 hours before his end.

The circumstances were surreal. I had lost another, very precious friend a few days before Michael and, following an accident, I had undergone a sixth operation on my leg that had led to infection and the need for further corrective surgery. So, obliged to lie with an elevated leg for 55 minutes each hour, either in pain or brimful of morphine, I read what Michael had written. What I remember best is the contrast between relentless rain beyond the window, incessant on the Somerset levels, and – in stark counterpoint – Michael’s dazzling intelligence on the page; his eyes twinkling through his glasses, in what remained of my imagination.

At first glance, Las Meninas appears to be what in Britain would be called a “conversation piece”, yet there is no conversation. Quite the reverse: there is a powerful mood in the room and it is silent – silence is the quintessence of the painting.

Here is Velázquez, in a family room at the royal palace, at work before a canvas, in the company of the king’s daughter and her entourage. But the first thing we notice is that most of the figures are frozen, their attention caught by, and focused on, some presence outside the frame. The gaze of those aware of this presence is in our direction, and apparently that of Velázquez’s sitter or subject. And that, one can presume from the reflection in the mirror on the back wall, is likely be King Philip IV and Queen Mariana, whose faded reflections we see, spectral, in the glass.

Michael recalls that it had been a book by French philosopher Michel Foucault,The Order of Things, written in 1966, that led him to look again at Las Meninas. Foucault wrote about the “corporeal gaze” of Velázquez himself, which creates “a condition of pure reciprocity” between painting and viewer. He added: “As soon as they place the spectator in the field of their gaze, the painter’s eyes seize hold of him, force him to enter the picture, assign him a place at once privileged and inescapable.” This idea of the “corporeal gaze” sent Michael back to Madrid to see the painting, whereupon he resolved to write the book.

Michael Jacobs came into my life too late, and even later in his. We were an unlikely combination – an aesthete bon vivant and a messed-up war correspondent – but our friendship was intense and immediate. We were introduced by a mutual friend: the three of us shared a passion for the south – Latin America, Italy, Spain – with all that means: the south as way of life as well as light; passion and profanity. So that in grim, soggy England we formed a triad of yearning for land where the olive grows, the bougainvillea and the vine.

After I met him, I devoured Michael’s writing on mythological painting, Andalucía and the Andes; the story of his grandfather building a railway across Bolivia. We met further, at literary festivals in Hay-on-Wye and Xalapa, Mexico – where I got to see the all-night Michael trying whatever drinks were on offer, speaking in waterfalls of Spanish and dancing in his way.

Finally I visited Michael and Jackie’s house, where I saw magnificent paintings by an artist whose work I greatly admired, Estella Solomons, an Irish republican who turned out to be Michael’s great-aunt. I was – still am – in the process of reviewing a collection of letters written to my great-aunt Gladys Hynes by Desmond Fitzgerald Snr when he was minister for propaganda in the revolutionary Provisional Dáil in Ireland just after the Easter Rising of 1916. The two ladies would almost certainly have known one another – Fitzgerald’s letters illustrate how republican and artistic circles overlapped in those days, and Michael and I loved to wonder where and how.

But our real bond was painting. Michael came to visit me at home after my accident; I was housebound and fitted with an Ilizarov frame from which pins penetrated a badly broken leg in order to stretch bone – in the manner of the Spanish Inquisition, as Michael eagerly pointed out.

Michael and I had already discussed his book on Velázquez briefly, and talked about his admiration for his PhD supervisor Anthony Blunt, and Michael’s loyalty to Blunt after his espionage was exposed.

But I think he was surprised to find a wall of my home lined with books about painting and I was gratified by his compliments on the collection. So now came our first real conversation about art, which concerned what we called “the dark renaissance” – Caravaggio and Giorgione, whose extraordinary Tempest had been an early obsession for both of us. I was bowled over: aged 59, I’d found my first soulmate beyond family in these matters, interested in both the mysteries of the paintings and existential depths they threatened to contain.

That conversation occurred in mid-September 2013. Michael, with his wanderlust, was sympathetic towards my enforced immobility – his idea of hell was to be parked off the road – and mentioned with passing irritation that he had to go to the doctor too. Ten days later, reports reached me that Michael had “between three and five years to live”.

My new friend – probably the most effervescent person I had ever encountered – was about to die. For some time, however, Michael insisted: “Of course, it’s nothing compared to what you’re going through, Ed.” Once, I dared to correct him: “Michael, there’s one big difference. My body wants me to get better, yours is out to get you.” “Quite so,” he agreed, and changed the subject.

Not long afterwards, Michael talked about how the book onLas Meninas should proceed, and how I might undertake some role towards that end; he accepted that he and I might need to work together in some way.

There was one unforgettable afternoon: I arrived at his house in Hackney, and we headed out for lunch at Michael’s favourite Italian trattoria, Ombra – which means shadow. I was barely able to walk; Michael was starting to hurt badly too – he had an orthopaedic chair installed at home. We made it about 500 yards on foot, then both decided that we really ought to take the bus, and rode one stop – my first bus journey since the accident, probably among Michael’s last. We were appalled at the notion that neither of us was able to enjoy a glass of wine with lunch, drugged as we were on morphine. The cook and waitresses were playing Fabrizio de André’s searing account of Bob Dylan’s Desolation Row translated as Via della Povertà, and with that devastating song drifting on the air, Michael and I began to discuss Las Meninas, and his book, in earnest.

The plan was for Michael to dictate his ideas on a regular basis; I would take notes and write them up for Michael to edit. Our second conversation was before a performance by the London Symphony Orchestra of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, for which we met early in the Barbican bar for discussion over more soft drinks. Michael was almost amused by the sight of us both hobbling, decrepit, to our seats, and joked at what a “psychedelic experience” it was to hear that particular piece, with its opium reveries and frantic, satanic passages, on a heavy dose of class A medication.

The third session – a long one – was back at Hackney, and the fourth at the corner of the table during what must have been one of Michael’s last big outings for dinner – at Patio, an excellent Polish bistro in Shepherd’s Bush. Even reluctantly sober and in pain, Michael was the life and soul of the table; he and I stole a while to ourselves during which he burst forth on Petrarch’s theories on composition, and said he was ready to start dictation.

He said the same a month later.

The problem, I think, was that embarking on this modus operandi signified an admission that he would die – and that was something he outwardly refused to do, almost until the last days. I think he felt that even to show me what he had already written was “bad voodoo”, and would hasten his end.

The plan was further interrupted by Michael’s determination to visit his real home at Frailes, in Andalucía, for Christmas and what he must have known would be a last goodbye to his dog, Chumberry, his people there and the landscape he loved.

For these reasons, I never actually sat down with him, notebook in hand, shorthand at the ready. What we did do, though, was to discuss Las Meninasduring what time we could steal while I took surreptitious notes, which I then wrote up each night after our meetings.

The last conversation was on Thursday 10 January, the day before Michael died, when a mutual friend Jon Lee Anderson and I visited St Bartholomew’s, either side of lunch at an Italian trattoria in Smithfield, wishing Michael was with us. A few nights later, Jon Lee, his wife, Erica, and I were sharing a cab from Michael’s funeral back to the West Country, swigging from a bottle of mezcal I had bought while with Michael in Mexico, but which had lasted longer than he did.

We’ll never actually know whether Michael found some key to definitively unlock the secrets of the painting, which has obsessed and defied many, including Courbet, Manet, Sargent, Whistler and Picasso, and which to Michael represented not only an allegory of life, but also “life itself”, as he put it. Michael’s point of departure is indeed “the confusion in Velázquez between painting and life itself”, but we’ll never know whether he breached this captivated bafflement or whether he, literally, died trying.

But we do know from the book he left unfinished that Michael’s text serves as a map and inspiration indispensable to the lover of painting – scholar or passionate amateur – who stares in wonder at Las Meninas or any painting which grapples with the enigma of representation. In Michael’s brilliant half-book, beyond a fragment, we have not only a typically Jacobs-esque narrative of his life with Velázquez – one of chance encounters, aperitifs, friendships, musings and restless autobiography – but the story of the picture’s own adventures, and this passionate manifesto for the liberation of how we look at painting, with our emotions and responses to it.

And we know something else, from what Michael confided during the weeks he had to entrust the book to someone: that our view of painting – and his view of this painting – changes as we approach death.

One unforgettable conversation concerned valedictory paintings. Michael chose – oddly, I thought at first – Manet’s final masterwork, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. A barmaid stands before a mirror in which the action is reflected – at an angle which is either impossible or the result of an optical trick by the artist, as is the case with the mirror in Las Meninas.

Sixteen months after Michael’s death, I was at the Inventing Impressionism exhibition at the National Gallery where another Folies-Bergère by Manet from a private collection was on show – different barmaid, possibly the same mirror. I was with my 16-year-old daughter, Claudia, and told her about Michael and his choice. “Well, it’s the Doppelgänger, isn’t it, Dad?” she said coolly. “You see yourself and you know you’re about to die.” I have no idea whether this had occurred to Michael, but it hadn’t occurred to me; it isn’t in the book, and should be.

Michael and I thus tiptoed towards another idea: the valedictory painting in the beholder’s eye; the way in which painting can change and reveal its meaning as one approaches death. Las Meninas was not Velázquez’s last painting but nearly, made four years before the painter’s death, as sudden as Michael’s, and at the same age.

Michael’s attention became progressively focused on the one person in Las Meninas who looks across the entire length of the room, as we do but from the back; the one figure who cannot see the mirror from where he stands, at the entrance to a brightly lit zone behind it. If Michael had a conclusion it concerned this mysterious figure, who appears to be looking back as he leaves through a door to a staircase. Or perhaps he has just arrived on the scene, but had a second thought, upon beholding the scene of family intimacy in the private royal quarters. In fact, this figure seems to be arriving and leaving at the same time, which, Michael thought, placed him outside time, and so making him a portrait of time in some way.

Early on in the book, Michael enthuses about “the possibility that the composition’s exact mathematics should harbour secret codes. The hint of wondrous worlds lying beyond the mirror and the open door beside it.” And as he grew ill, he calculated that although there are too many vanishing points in the painting for the perspective lines to converge at any single point, they do all run through that open door, to dissipate in the light beyond it.

A lot of ink has been spent on how Las Meninas represents life, but none on how it represents death. “He’s moving over to the other side,” said Michael one day. “That’s what the picture is about, Ed,” he said, “life itself and life’s decay until we reach the other side. And that’s where our vanishing points come to rest – through that door, up those stairs, to the other side of the doorway he’s standing in.”

Michael believed that in Las Meninas Velázquez admits us “behind his eye”. But what was behind Michael’s eye? The place behind Michael’s eye was in turn behind the open door at the back; wherever the mysterious figure is heading, urging us to follow with his gaze and the swing of his cloak. Beyond the open door, which Michael now called “the other side”, lay the obliteration he faced. This haunting figure had become to Michael a mutation of Charon crossing the Styx, looking back at him, head cocked as if to beckon, already two steps up the stairs beyond the panelled wooden door, towards the vanishing point bathed in light, into which Michael himself was vanishing.

Everything Is Happening: Journey into a Painting by Michael Jacobs, with an introduction and coda by Ed Vulliamy, is published by Granta Books, £15.99.