Tate Britain, London

This magnificent exhibition of 300 images reveals Blake’s inspiring vision at its most vivid and strange

This magnificent exhibition of 300 images reveals Blake’s inspiring vision at its most vivid and strange

Laura Cummings

The Observer

15 September 2019

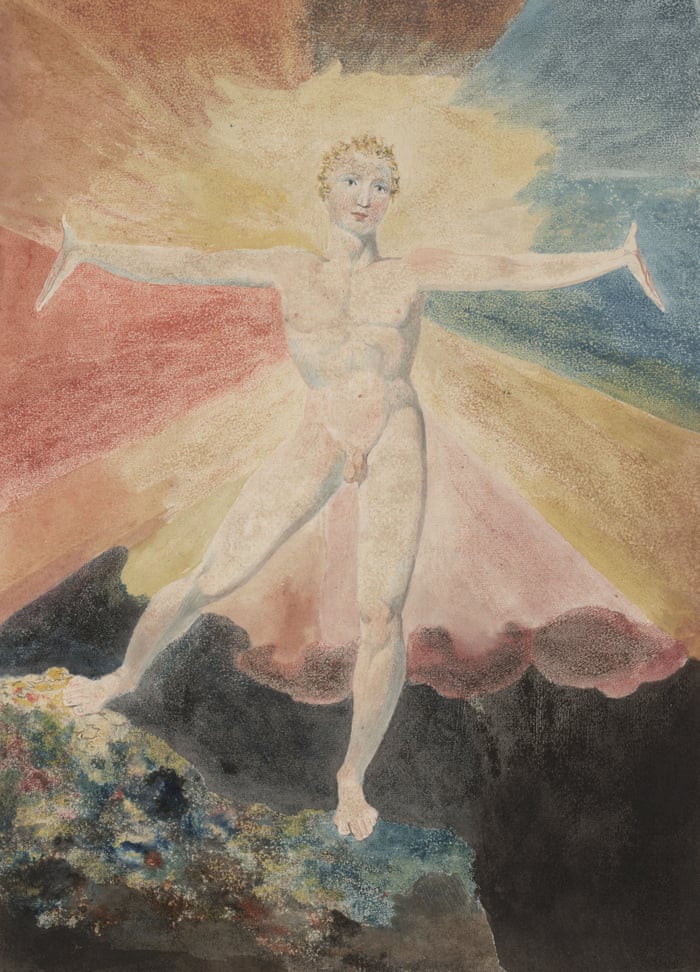

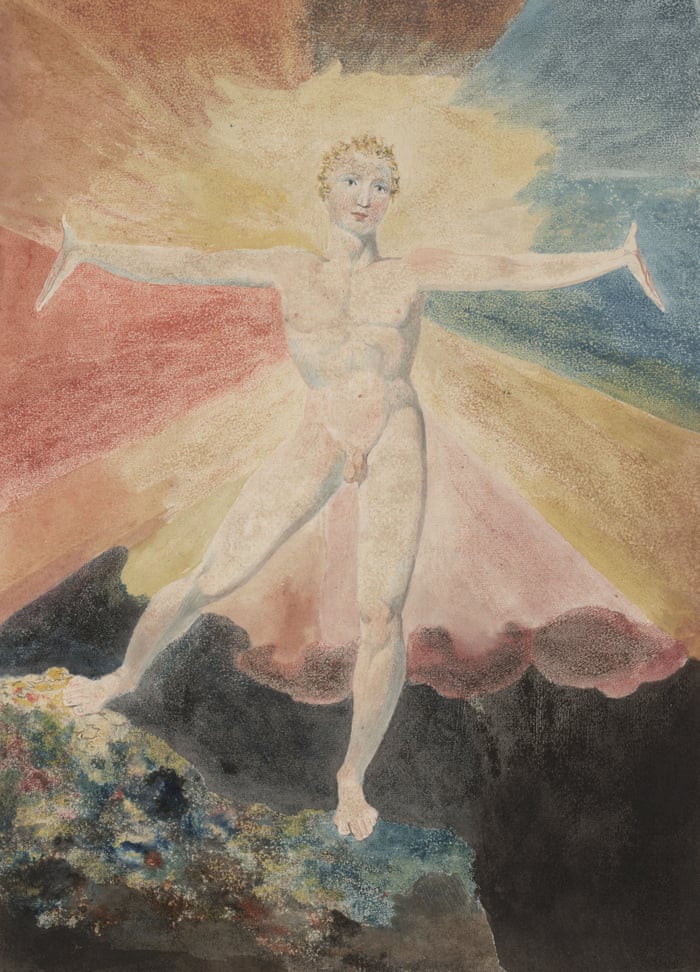

This stupendous show opens with a starburst: the naked figure of Albion rising in glory, rainbows exploding around his outstretched arms. It is a curtain-raiser, a full frontal performance: the beautiful dancer in mid-sashay on the edge of a cliff, bringing light to dispel the darkness. And Albion’s arms are holding out for more – welcoming this new dawn, inviting us all to rise up with him. It is the great wake-up call of British art.

Albion Rose, c179315 September 2019

This stupendous show opens with a starburst: the naked figure of Albion rising in glory, rainbows exploding around his outstretched arms. It is a curtain-raiser, a full frontal performance: the beautiful dancer in mid-sashay on the edge of a cliff, bringing light to dispel the darkness. And Albion’s arms are holding out for more – welcoming this new dawn, inviting us all to rise up with him. It is the great wake-up call of British art.

But what does it mean, this spectacular engraving? Albion represents England (and primeval man) in the made-up mythologies of William Blake (1757-1827). But many people believe this is not Albion so much as the personification of freedom, imagination, independence. Shake off those mind-forg’d manacles, rebel against conservatism, slavery, organised religion, even tight clothes: interpretations of the image are ceaselessly at odds.

Everyone knows that Blake is art’s original free spirit. He is against science, the establishment, the Age of Reason. Yet this radiant figure might be the very emblem of Enlightenment thinking, just as it could be the angel Gabriel, a prelapsarian Lucifer, or the spirit of political awakening.

The curators of this colossal survey, the first on such a scale in nearly 20 years, are wise to point out the almost impenetrable complexities of Blake’s thinking from the start. Their aim is to throw the focus on his works as images, as opposed to emblems – tiny, teeming visions of gods, monsters and wild scenarios taking place at the bottom of the ocean or outer space, but above all in the free world of Blake’s imagination.

He is rightly presented here as the most radical of leftfield artists. The son of a Soho shopkeeper who stumped up the money for drawing lessons and his son’s apprenticeship to an engraver at 14, Blake studied for about a year at the Royal Academy. He learned to loathe the conformism of both the institution and its president, Joshua Reynolds. There was only one show – an unqualified disaster held above the Soho shop, with not a work sold. All his life, Blake kept having to make engravings of other people’s art.

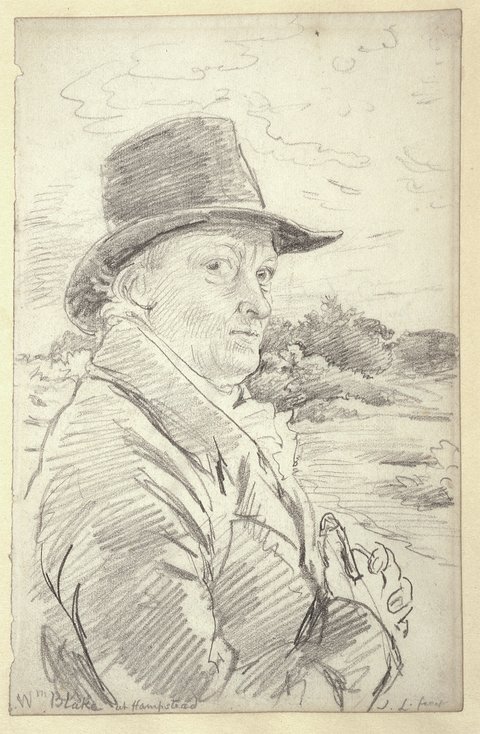

Except for the occasional hint of a Regency sideburn, however, his art reflects nothing of Georgian London. An unconfirmed self-portrait in the first gallery shows the artist with an intense but entirely in-turned gaze, plus that same startling symmetry that characterises so much of his work; images stream out of his mind, not in through his eyes. The critic of Blake’s one and only show – an unqualified disaster, held above the shop – thought he was eccentric, not to say mad.

Possible self-portrait it from 1802

And Blake’s art remains irreducibly strange. Familiarity cannot diminish the utter singularity of his home-grown aesthetic: heads floating on columns of transparent Lycra-like material, rippling up towards multicoloured skies or gathering in tumultuous spirals. Saints diving through the firmament, devils flickering like fire, angels back-crawling through transparent seas. Lone bodies are shown in convulsion, drowning, paralysed or hunched tight as padlocks. Unbound, they appear spreadeagled, levitating, or hurtling upwards like the bellowed flames up a chimney.

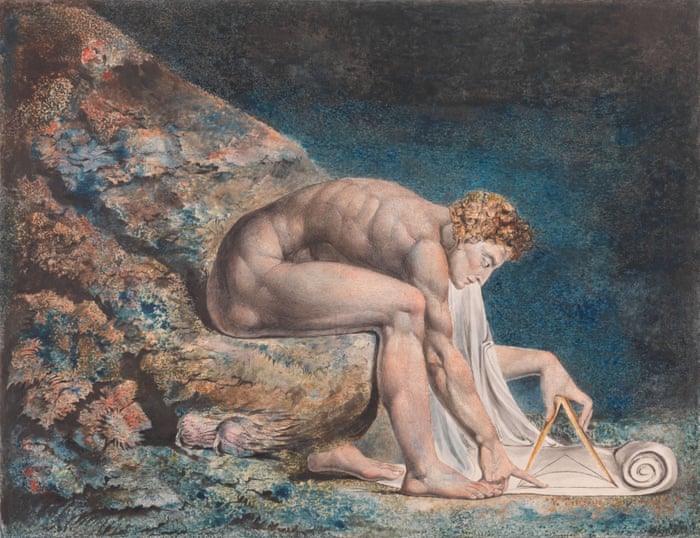

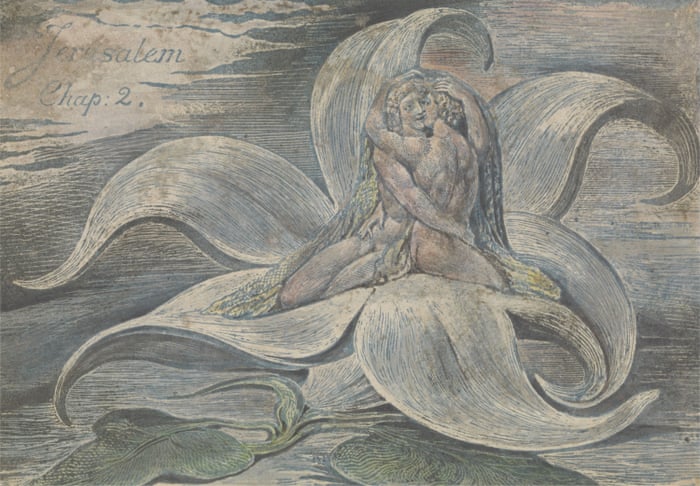

Moses holds up the tablets: a rocket man just about to lift off. Adam and Eve, with their high waists and Blake’s weirdly pronounced muscle groups, perform a nude pas de deux. Men and women look alike, and both at times resemble a stylised version of his self-portrait, with its fixated eyes. Tulips make love, lovers couple inside flowers, fleas are reincarnated as titans. Newton does his pointless calculations – as if the world could possibly be measured – at the bottom of an inky blue sea.

Could anyone, without benefit of scholarship, honestly interpret that marvellous icon as a diatribe against Newton and all his works? Can anyone really tell the difference between Blake’s The Ancient of Days, with his wind-blown beard and lightning-bolt dividers, and his doppelganger in the imaginary The Book of Urizen, representative of science and unfreedom? These visual archetypes appear interchangeable, evenly distributed across the moral spectrum. And walking through this immense show – 300 works and more – it becomes obvious that good and evil may well have the same face or physique in Blake’s conceit. After all, Lucifer eventually becomes Satan.

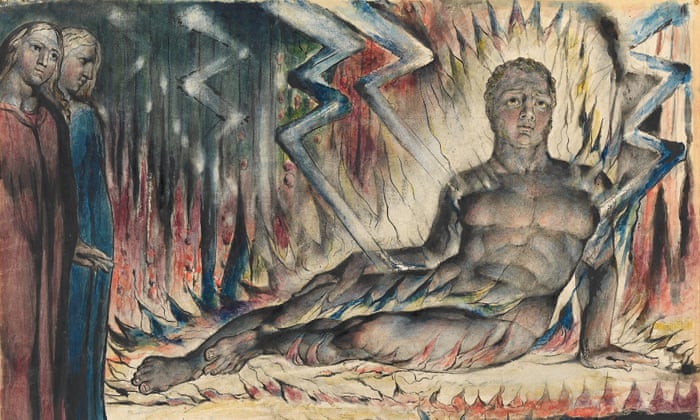

Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils, c.1826

In his visions, the devil may be tragic, tortured by interminable regret; and God may be violent, uprooting Adam like a weed from the earth. Horror is not always frightening. One illustration of hell shows a smoking serpent front of stage in a kind of glamorous limelight. Cerberus has at least one head resembling a London dog.

Cerberus, 1824-7

This late ink and watercolour painting is unusually large for Blake, about the size of a hardback book. In the early years, his paintings looked like outsize black and white prints, scenes from the Bible done in greyscale, all hieratic poses, super-long bodies and neo-Gothic drapes, based on his fascination with Queen Eleanor’s medieval tomb in Westminster Abbey. But quite soon they shrink in size, even as they expand pictorially; to paraphrase Blake: infinity in the palm of your hand.

Christ in the Sepulchre, guarded by Angels, c. 1805

Ideas proliferate as images. A wild scrimmage of monkeys: evolution condensed. Infants so joyful they hover in the air like butterflies. Urizen falls to earth like a comet, a diver, or an Olympic gymnast balanced head down on a beam. God, in one supreme vision, is shown creating the entire world in the act of opening the pages of an illustrated book.

Nobody made books like William Blake. He pioneered the technique of relief etching, in which everything but his images and words – which had to be written backwards – was corroded from the plate. The words appear in his own handwriting; the images are hand-touched by Blake, and also by Catherine, so that they look like individual watercolours. Working this way, Blake freed himself and his art from traditional printing and existing typefaces.

Jerusalem, plate 28, 1820

In displaying them bound up as printed books, as well as separately, in the individual sheets prized by museums all over the world, the curators emphasise Blake’s unique enterprise on paper. Everything he imagined – radiant planets, swooping angels, infernal pile-ups – was choreographed in terms of the illuminated page. Scenes float like vignettes – a star-spangled heaven top right, the lamb of God lying down bottom left – or merge with the words themselves, passing through them like the very things depicted: rivers, fireballs, gusting winds.

"The Lamb" published in Songs of Innocence in 1789

Sometimes the script is so tiny it is almost illegible, particularly when there is so much going on between the lines. It is astonishing to spot proper names like Washington and Tom Paine on a page, in the poem America, beneath a dazzling image of Urizen lying back on an armchair composed of storm clouds. And while the words are an indelible exhortation to freedom in themselves – freedom from slavery, or British rule, freedom from conventional marriage or dark Satanic mills – the images carry that idea of liberty as a graphic principle.

In displaying them bound up as printed books, as well as separately, in the individual sheets prized by museums all over the world, the curators emphasise Blake’s unique enterprise on paper. Everything he imagined – radiant planets, swooping angels, infernal pile-ups – was choreographed in terms of the illuminated page. Scenes float like vignettes – a star-spangled heaven top right, the lamb of God lying down bottom left – or merge with the words themselves, passing through them like the very things depicted: rivers, fireballs, gusting winds.

"The Lamb" published in Songs of Innocence in 1789

Sometimes the script is so tiny it is almost illegible, particularly when there is so much going on between the lines. It is astonishing to spot proper names like Washington and Tom Paine on a page, in the poem America, beneath a dazzling image of Urizen lying back on an armchair composed of storm clouds. And while the words are an indelible exhortation to freedom in themselves – freedom from slavery, or British rule, freedom from conventional marriage or dark Satanic mills – the images carry that idea of liberty as a graphic principle.

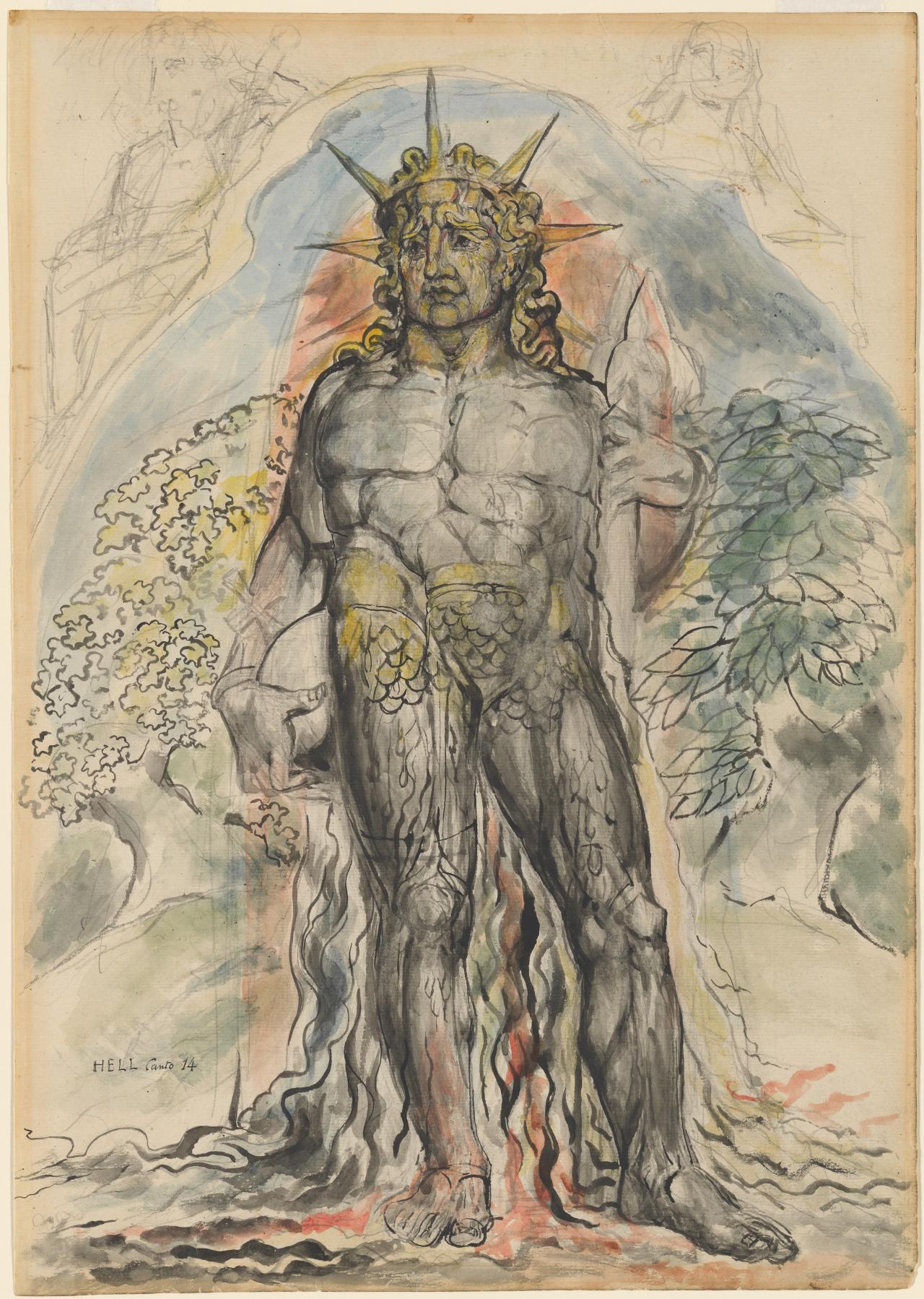

The Symbolic Figure of the Course of Human History Described by Virgil, 1824-1827

Blake may depict Apollo dancing like a prima ballerina, or Death taking a bow. The Symbolic Figure of the Course of Human History Described by Virgil is – amazingly – a dead ringer for the Statue of Liberty, complete with spiky diadem and torch. It is impossible to believe that Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi hadn’t seen Blake’s watercolour when he designed his monument.

Every figure must fit the page – sometimes deliberately fighting its limitations, in the case of the eternal prophet Los, howling in despair against the imprisoning walls of his box. But the page is also the source of true freedom. Everything can go wild within the fierce symmetry of Blake’s art – man becomes Superman, angels are skydivers, gods and prophets are shape-shifting wraiths and every sinew is visible beneath those see-through garments because everything is vision transcribed; figments of line and wash on the airy page.

Peering into these tiny pictures, you keep seeing premonitions of our present times: factionalism, violence, stupidity, oppression. But it would be hard to think of a more encouraging artist; and that is a matter of images, beyond words. Blake’s figures are designed to inspire: urging you to stand up, rise up, embrace your fellow man and woman with their surging uplift, distilled in Albion rising. His whole being was devoted to freedom, his art a perpetual call to arms.

•William Blake is at Tate Britain, London SW1 until 2 February

Three stars of the Blake show

Nebuchadnezzar 1795-1805

The king of Babylon is a terrible warning to us all: “those that walk in pride, the Lord can abase”. Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar has been so abased it is by now a hybrid of man and beast, crawling the Earth on his hands and knees, skin like hide, toes turning into griffin’s talons.

'Europe' Plate i: Frontispiece, 'The Ancient of Days' 1827

The divine white-beard, reaching down from his burning disc to measure the Earth below with his shining dividers. For all the force and similarity, this is not in fact God but Blake’s Urizen, the despised personification of Reason and Science.

The River of Life 1805

A family streams up the transparent waters of this winding river, hand in hand, past classical buildings and towards a shining golden sun. Everything flows onwards towards the light, in one of Blake’s most radiant visions of happiness.

John Linnell - William Blake at Hampstead wearing a hat, c.1825

Heavenly visions of hell: Alan Moore on the sublime art of William Blake

Blake’s Lambeth home was also the scene of the spiritual apparitions captured in a major new Tate exhibition, writes the graphic novelist

Alan Moore

The Guardian

Friday 30 Aug 2019

Friday 30 Aug 2019

When we speak of the poetry or painting of place, we generally refer to words and images that celebrate or else investigate some fixed location. And yet, given that all creative works have arisen from whatever influences surrounded their geographic point of composition, surely all art could be said to be the art of place, something that could only have emerged from that specific spot at that specific time? A city, a field, a house, a street: all of these have their own aura, their own atmosphere, a lyric condensation born of memory and history. Might it be, however, that some places have not only an embedded past, but an embedded future also? Could some works of art be already contained within their site of origin, immanent and waiting for discovery, for realisation?

If we imagine the material world about us having a concealed component of the fictional and the fantastic, visions buried in its stones and mortar waiting for their revelation, then we may suppose that 18th-century Lambeth was a teeming hub of such imaginal biodiversity. Bedlam alone could account for this ethereal population boom, but then nearby was the Hercules Buildings residence of William Blake, which can have only added to the sublime infestation.

Blake’s house is long gone, with nothing but the Herculean mural decorating a replacement block of flats nodding to its memory. Other than some contemporary depictions, all we know about the place is of the incidents that he, his wife and their associates reported as occurring there. There is a drawing of William and Catherine in their bedroom that radiates a scuffed contentment. There are the naturist anecdotes suggesting that the couple had repurposed their back garden as an urban Eden. But the place that would seem to have harboured the most startling idea-forms is the liminal, transitional space represented by the stairway, hall and landing. It was here that Blake was introduced to two of his most memorable phantasms – the glowering Ancient of Days and the macabre Ghost of a Flea.

The last of these, painted 25 years after the former, was the first to be encountered. Blake and Catherine moved into 13 Hercules Buildings in 1790, and according to Blake’s biographer Alexander Gilchrist, in that same year Blake described his only sighting of what he believed to be a ghost. Speckled and scaly, the appalling apparition had rushed down the stairs at him, driving him out into his Edenic garden, more afraid than he had ever been before; would ever be again. Then, Blake was witness to a second visitation, of a very different nature and yet once more manifested near the stairhead, hovering above the landing.

'Europe' Plate i: Frontispiece, 'The Ancient of Days' 1827

If we imagine the material world about us having a concealed component of the fictional and the fantastic, visions buried in its stones and mortar waiting for their revelation, then we may suppose that 18th-century Lambeth was a teeming hub of such imaginal biodiversity. Bedlam alone could account for this ethereal population boom, but then nearby was the Hercules Buildings residence of William Blake, which can have only added to the sublime infestation.

Blake’s house is long gone, with nothing but the Herculean mural decorating a replacement block of flats nodding to its memory. Other than some contemporary depictions, all we know about the place is of the incidents that he, his wife and their associates reported as occurring there. There is a drawing of William and Catherine in their bedroom that radiates a scuffed contentment. There are the naturist anecdotes suggesting that the couple had repurposed their back garden as an urban Eden. But the place that would seem to have harboured the most startling idea-forms is the liminal, transitional space represented by the stairway, hall and landing. It was here that Blake was introduced to two of his most memorable phantasms – the glowering Ancient of Days and the macabre Ghost of a Flea.

The last of these, painted 25 years after the former, was the first to be encountered. Blake and Catherine moved into 13 Hercules Buildings in 1790, and according to Blake’s biographer Alexander Gilchrist, in that same year Blake described his only sighting of what he believed to be a ghost. Speckled and scaly, the appalling apparition had rushed down the stairs at him, driving him out into his Edenic garden, more afraid than he had ever been before; would ever be again. Then, Blake was witness to a second visitation, of a very different nature and yet once more manifested near the stairhead, hovering above the landing.

'Europe' Plate i: Frontispiece, 'The Ancient of Days' 1827

This forbidding figure, Blake’s Ancient of Days, was worked immediately into his evolving personal mythology, and would become the frontispiece for his 1794 publication Europe a Prophecy. This stern primordial entity makes his exact and calculated judgment from a throne amid the clouds, above the mundane darkness of the world. His seat is possibly the sun itself, but is here shown as a concavity; one of Blake’s “chariots of fire”, or else the ostentatious 1960s swivel chair of a Bond villain.

The dividers with which this windswept creator makes his moral measurements, along with something of the posture, crouching and absorbed, would recur a year later in Blake’s Newton. The father of thermodynamics’ deified and Apollonian appearance is most probably satirical, a marker of vainglorious ambition, and this same authoritarian conceit is evident in Blake’s judgmental Ancient as, like Newton, he divides the cosmos into motion, heat and gravity. This, perhaps born of Blake’s Moravian parentage or the dissenting Christian faiths that he grew up with, seems a Gnostic view of the Almighty as self-glorifying tyrant, manufacturing a penitentiary material universe that it might worship him. Blake was a proto-anarchist. In his reaction to this second hallway visitation we can see him turn his huge, radical eyes on conventional religion, where he finds that pasture wanting.

Twenty years would pass before the earlier and more aggressive of Blake’s Lambeth spectres would be conjured into visible, malign existence as a fresco, worked in tempera and gold on a hardwood panel, tiny even in comparison with his other unusually small compositions. The peculiar circumstances of this late revisiting invite examination: in 1818, by now living with Catherine at their South Molton Street address, Blake had been visited by his friend and patron, the astrologically infatuated watercolourist John Varley. As the conversation turned to Blake’s sole sighting of a ghost, two decades earlier in Lambeth, Varley asked for a description of the phantom and, in what must have been a spine-tingling moment, Blake claimed that he saw the creature there before them as they spoke and asked Varley to pass him his drawing materials.

There is an eerily persuasive incident halfway through this part seance/part sitting as described by Varley, when Blake paused in his delineation and explained that his uncanny model had just let its mouth fall open, forcing him to work on a detail of the jaw until his subject had resumed its pose. By the next year, Varley, a frustrated spiritualist who had never seen a spirit, had commissioned Blake to work the sketch into a finished portrait as part of a proposed series titled Visionary Heads. And so, in 1819, Blake’s horrific visitor of 1790 finally stepped out on to a stained and creaking stage, making its debut in the muddy world of matter and sensation.

The Ghost of a Flea, c 1819

As imagined by the Lambeth angel whisperer, the threatening and somehow smug abomination is theatrical in its demeanour, consciously performing for the viewer. Glossed by Blake, the flea is the transposed soul of a murderer trapped in a form that, while both bloodthirsty and powerful, is too small to become a mighty engine of destruction. Thus condemned, it struts its miniature domain and makes a swaggering display of cruelties that it can no longer accomplish. With nothing save an acorn cap to represent its drinking bowl of blood, with nothing but a thorn to serve as improvised prison yard shiv, this former demon is demoted and no longer dangerous. In its fallen state, more mischievous than malefic now, the has-been homicidal maniac is almost poignant.

Framed by threadbare curtains with a plunging star upon its painted backdrop, something in the monster’s owl-like stare and heavy posture led me to recruit it as a premonition of Sir William Withey Gull, the posited Jack the Ripper in From Hell, my work with Eddie Campbell. Once again, there is the sense of something that once had its own imagined grandeur, its own self-exonerating black magnificence, reduced now to a sordid tabloid narrative of pointless butchery; a banal flea-bite on the wrist of history. The gothic nightmare licks its chops and postures on its narrow platform, in a sour astral miasma. Weathered and distressed, the craquelure and mottling only enhance the glimmering murk in which the violent wraith enacts its purgatory, treading the discoloured boards, the sky forever falling.

In the hallway of No 13 Hercules Buildings, Blake beheld both austere deities and trampled devils. It is to the credit of his generous and blazing soul that heaven was not spared his fierce, critical gaze, nor hell his sympathy.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/aug/30/from-heaven-and-hell-alan-moore-on-the-sublime-visions-of-william-blake

Fascinating article, I never realised the dreaded diabolical Flea's cup was an acorn...

ReplyDelete