'This tape rewrites everything we knew about the Beatles'

Mark Lewisohn knows the Fab Four better than they knew themselves. The expert’s tapes of their tense final meetings shed new light on Abbey Road – and inspired a new stage show

Richard Williams

The Guardian

Wed 11 Sep 2019

The Beatles weren’t a group much given to squabbling, says Mark Lewisohn, who probably knows more about them than they knew about themselves. But then he plays me the tape of a meeting held 50 years ago this month – on 8 September 1969 – containing a disagreement that sheds new light on their breakup.

They’ve wrapped up the recording of Abbey Road, which would turn out to be their last studio album, and are awaiting its release in two weeks’ time. Ringo Starr is in hospital, undergoing tests for an intestinal complaint. In his absence, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison convene at Apple’s HQ in Savile Row. John has brought a portable tape recorder. He puts it on the table, switches it on and says: “Ringo – you can’t be here, but this is so you can hear what we’re discussing.”

What they talk about is the plan to make another album – and perhaps a single for release in time for Christmas, a commercial strategy going back to the earliest days of Beatlemania. “It’s a revelation,” Lewisohn says. “The books have always told us that they knew Abbey Road was their last album and they wanted to go out on an artistic high. But no – they’re discussing the next album. And you think that John is the one who wanted to break them up but, when you hear this, he isn’t. Doesn’t that rewrite pretty much everything we thought we knew?”

Lewisohn turns the tape back on, and we hear John suggesting that each of them should bring in songs as candidates for the single. He also proposes a new formula for assembling their next album: four songs apiece from Paul, George and himself, and two from Ringo – “If he wants them.” John refers to “the Lennon-and-McCartney myth”, clearly indicating that the authorship of their songs, hitherto presented to the public as a sacrosanct partnership, should at last be individually credited.

Then Paul – sounding, shall we say, relaxed – responds to the news that George now has equal standing as a composer with John and himself by muttering something mildly provocative. “I thought until this album that George’s songs weren’t that good,” he says, which is a pretty double-edged compliment since the earlier compositions he’s implicitly disparaging include Taxman and While My Guitar Gently Weeps. There’s a nettled rejoinder from George: “That’s a matter of taste. All down the line, people have liked my songs.”

John reacts by telling Paul that nobody else in the group “dug” his Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, a song they’ve just recorded for Abbey Road, and that it might be a good idea if he gave songs of that kind – which, John suggests, he probably didn’t even dig himself – to outside artists in whom he had an interest, such as Mary Hopkin, the Welsh folk singer. “I recorded it,” a drowsy Paul says, “because I liked it.”

A mapping of the tensions that would lead to the dissolution of the most famous and influential pop group in history is part of Hornsey Road, a teasingly titled stage show in which Lewisohn uses tape, film, photographs, new audio mixes of the music and his own matchless fund of anecdotes and memorabilia to tell the story of Abbey Road, that final burst of collective invention.

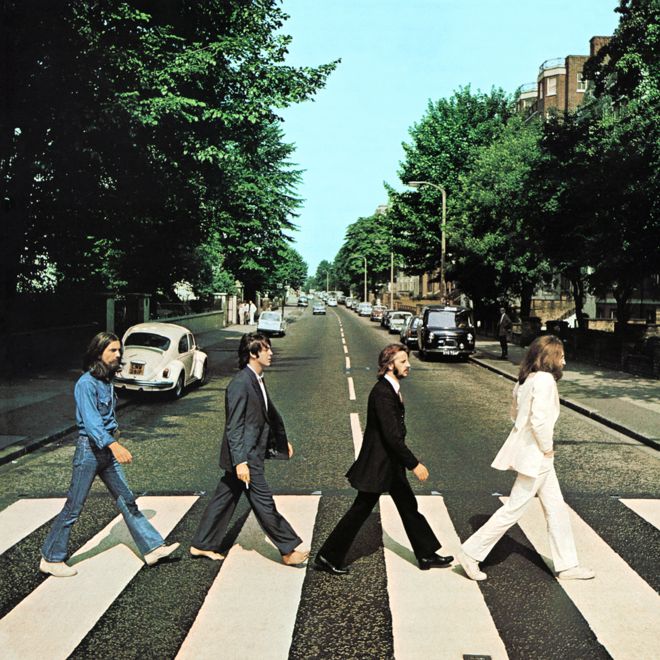

The album is now so mythologised that the humdrum zebra crossing featured on its celebrated cover picture is now officially listed as site of special historic interest; a webcam is trained on it 24 hours a day, observing the comings and goings of fans from every corner of the world, infuriating passing motorists as these visitors pause to take selfies, often in groups of four, some going barefoot in imitation of Paul’s enigmatic gesture that August morning in 1969.

“It’s a story of the people, the art, the people around them, the lives they were leading, and the break-up,” Lewisohn says. The show comes midway through his writing of The Beatles: All These Years, a magnum opus aiming to tell the whole story in its definitive version. The first volume, Tune In, was published six years ago, its mammoth 390,000-word narrative ending just before their first hit. (“All the heft of the Old Testament,” the Observer’s Kitty Empire wrote, “with greater forensic rigour.”)

Constant demands to know when Turn On (covering 1963-66) and Drop Out (1967-69) might appear are met with a sigh: “I’m 61, and I’ve got 14 or 15 years left on these books. I’ll be in my mid-70s when I finish.” Time is of the essence, he adds, perhaps thinking of the late John Richardson’s uncompleted multi-volume Picasso biography. This two-hour show is a way of buying the time for him to dive back into the project.

For 30 years, Lewisohn has been the man to call when you needed to know what any of the Fab Four was doing on almost any day of their lives, and with whom they were doing it. His books include a history of their sessions at what were then known as the EMI Recording Studios in Abbey Road, and he worked on the vast Anthology project in the 90s.

Wed 11 Sep 2019

The Beatles weren’t a group much given to squabbling, says Mark Lewisohn, who probably knows more about them than they knew about themselves. But then he plays me the tape of a meeting held 50 years ago this month – on 8 September 1969 – containing a disagreement that sheds new light on their breakup.

They’ve wrapped up the recording of Abbey Road, which would turn out to be their last studio album, and are awaiting its release in two weeks’ time. Ringo Starr is in hospital, undergoing tests for an intestinal complaint. In his absence, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison convene at Apple’s HQ in Savile Row. John has brought a portable tape recorder. He puts it on the table, switches it on and says: “Ringo – you can’t be here, but this is so you can hear what we’re discussing.”

What they talk about is the plan to make another album – and perhaps a single for release in time for Christmas, a commercial strategy going back to the earliest days of Beatlemania. “It’s a revelation,” Lewisohn says. “The books have always told us that they knew Abbey Road was their last album and they wanted to go out on an artistic high. But no – they’re discussing the next album. And you think that John is the one who wanted to break them up but, when you hear this, he isn’t. Doesn’t that rewrite pretty much everything we thought we knew?”

Lewisohn turns the tape back on, and we hear John suggesting that each of them should bring in songs as candidates for the single. He also proposes a new formula for assembling their next album: four songs apiece from Paul, George and himself, and two from Ringo – “If he wants them.” John refers to “the Lennon-and-McCartney myth”, clearly indicating that the authorship of their songs, hitherto presented to the public as a sacrosanct partnership, should at last be individually credited.

Then Paul – sounding, shall we say, relaxed – responds to the news that George now has equal standing as a composer with John and himself by muttering something mildly provocative. “I thought until this album that George’s songs weren’t that good,” he says, which is a pretty double-edged compliment since the earlier compositions he’s implicitly disparaging include Taxman and While My Guitar Gently Weeps. There’s a nettled rejoinder from George: “That’s a matter of taste. All down the line, people have liked my songs.”

John reacts by telling Paul that nobody else in the group “dug” his Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, a song they’ve just recorded for Abbey Road, and that it might be a good idea if he gave songs of that kind – which, John suggests, he probably didn’t even dig himself – to outside artists in whom he had an interest, such as Mary Hopkin, the Welsh folk singer. “I recorded it,” a drowsy Paul says, “because I liked it.”

A mapping of the tensions that would lead to the dissolution of the most famous and influential pop group in history is part of Hornsey Road, a teasingly titled stage show in which Lewisohn uses tape, film, photographs, new audio mixes of the music and his own matchless fund of anecdotes and memorabilia to tell the story of Abbey Road, that final burst of collective invention.

The album is now so mythologised that the humdrum zebra crossing featured on its celebrated cover picture is now officially listed as site of special historic interest; a webcam is trained on it 24 hours a day, observing the comings and goings of fans from every corner of the world, infuriating passing motorists as these visitors pause to take selfies, often in groups of four, some going barefoot in imitation of Paul’s enigmatic gesture that August morning in 1969.

“It’s a story of the people, the art, the people around them, the lives they were leading, and the break-up,” Lewisohn says. The show comes midway through his writing of The Beatles: All These Years, a magnum opus aiming to tell the whole story in its definitive version. The first volume, Tune In, was published six years ago, its mammoth 390,000-word narrative ending just before their first hit. (“All the heft of the Old Testament,” the Observer’s Kitty Empire wrote, “with greater forensic rigour.”)

Constant demands to know when Turn On (covering 1963-66) and Drop Out (1967-69) might appear are met with a sigh: “I’m 61, and I’ve got 14 or 15 years left on these books. I’ll be in my mid-70s when I finish.” Time is of the essence, he adds, perhaps thinking of the late John Richardson’s uncompleted multi-volume Picasso biography. This two-hour show is a way of buying the time for him to dive back into the project.

For 30 years, Lewisohn has been the man to call when you needed to know what any of the Fab Four was doing on almost any day of their lives, and with whom they were doing it. His books include a history of their sessions at what were then known as the EMI Recording Studios in Abbey Road, and he worked on the vast Anthology project in the 90s.

Fan photos of (clockwise from top left) Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, John Lennon and George Harrison used in Lewisohn’s show Hornsey Road. Photograph: Courtesy Mark Lewisohn

The idea for a stage show was inspired by an invitation from a university in New Jersey to be the keynote speaker at a three-day symposium on the Beatles’ White Album, then celebrating its golden jubilee. His presentation, called Double Lives, juxtaposed the making of the album and the lives they were leading as individuals outside the studio. “It took several weeks to put together, and I thought, ‘This is mad – I should be doing this more than once to get more people to see it.’”

The next anniversary to present itself was that of Abbey Road, which took place during a crowded year in which Paul married Linda Eastman, John and Yoko went off on their bed-ins for peace, George’s marriage to Pattie Boyd was breaking up, and they were all involved in side projects. John had released Give Peace a Chance as the Plastic Ono Band and George had been spending time in Woodstock with Bob Dylan.

John also took Yoko and their two children, Kyoko and Julian, on a sentimental road trip to childhood haunts in Liverpool, Wales and the north of Scotland, ending when he drove their Austin Maxi into a ditch while trying to avoid another car. Brian Epstein, their manager, had died the previous year and the idealism that had fuelled the founding of their Apple company – “It’s like a top,” John said. “We set it going and hope for the best” – was starting to fray badly. Other business concerns – such as their song-publishing copyrights, which had been sold without their knowledge – led to a war between Allen Klein, the hard-boiled New York record industry veteran invited by John to sort it out, and John Eastman, Linda’s father, a top lawyer brought in by Paul to safeguard his interests.

Lewisohn has the minutes of another business meeting, this time at Olympic Studios, where the decision to ratify Klein’s appointment was approved by three votes to one (Paul), the first time the Beatles had not spoken with unanimity. “It was the crack in the Liberty Bell,” Paul said. “It never came back together after that one. Ringo and George just said, whatever John does, we’re going with. I was actually trying, in my mind, to save our future.”

And yet Lewisohn challenges the conventional wisdom that 1969 was the year in which they were at each other’s throats, storming out of the recording sessions filmed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg for the verité-style movie Let It Be, and barely on speaking terms. During the making of Abbey Road, says Lewisohn, “they were in an almost entirely positive frame of mind. They had this uncanny ability to leave their problems at the studio door – not entirely, but almost.”

In fact, Abbey Road was not the only recording location for the album: earlier sessions were held at Olympic in Barnes and Trident in Soho. And Lewisohn’s creation is called Hornsey Road because that, in other circumstances, is what the album might have been titled, had EMI not abandoned its plans to turn a converted cinema in that rather grittier part of north London into its venue for pop recording.

The show, Lewisohn believes, is the first time an album has been treated to this format. “People will be able to listen with more layers and levels of understanding,” he says. “When you go to an art gallery, you hope that someone, an expert, will tell you what was happening when the artist painted a particular picture. With these songs, I’m going to show the stories behind them and the people who made them, and what they were going through at the time. Certainly, no one who sees this show will ever hear Abbey Road in the same way again.”

• Hornsey Road is at the Royal and Derngate, Northampton, on 18 September and touring until 4 December.

No comments:

Post a Comment