Thursday, 28 February 2019

Tuesday, 26 February 2019

Elizabethan Miniatures at The National Portrait Gallery - review

National Portrait Gallery, London

Sharp sight, close scrutiny and an unbelievably steady hand unite in these exquisite Elizabethan miniatures – among the greatest works in European art

Laura Cumming

The Observer

Sun 24 Feb 2019

The man in the picture is on fire with love. Flames surge and ripple around him. Dressed in nothing but a fine lawn undershirt, open almost to the waist, hair slicked back from his beautiful face in the heat, he is all ready for the beloved. A woman whose identity is revealed – if only we could make it out – in the miniature dangling from a chain round his neck, a portrait even smaller than this one. She gave herself to him, in private, and now he offers himself in return: a lover burning with passion.

Nicholas Hilliard’s Unknown Young Man Against a Background of Flames is a stupendous painting – overwhelmingly potent and erotic. Yet it is not quite three inches tall. An object made to be held in the hand, to be touched, examined, even kissed, it nonetheless has the full force of a life-size portrait, the lover so fully present as to appear immediately recognisable (a young Ciarán Hinds), his message conveyed with dramatic urgency. And Hilliard goes further, exploiting the diminutive scale as no conventional portraitist could. The flames are scattered with powdered gold so that when the picture is turned this way and that, the fire of love leaps into life.

Sun 24 Feb 2019

The man in the picture is on fire with love. Flames surge and ripple around him. Dressed in nothing but a fine lawn undershirt, open almost to the waist, hair slicked back from his beautiful face in the heat, he is all ready for the beloved. A woman whose identity is revealed – if only we could make it out – in the miniature dangling from a chain round his neck, a portrait even smaller than this one. She gave herself to him, in private, and now he offers himself in return: a lover burning with passion.

Nicholas Hilliard’s Unknown Young Man Against a Background of Flames is a stupendous painting – overwhelmingly potent and erotic. Yet it is not quite three inches tall. An object made to be held in the hand, to be touched, examined, even kissed, it nonetheless has the full force of a life-size portrait, the lover so fully present as to appear immediately recognisable (a young Ciarán Hinds), his message conveyed with dramatic urgency. And Hilliard goes further, exploiting the diminutive scale as no conventional portraitist could. The flames are scattered with powdered gold so that when the picture is turned this way and that, the fire of love leaps into life.

Unknown Man Against a Background of Flames, by Nicholas Hilliard, c1600. Photograph: Clare Johnson/Victoria and Albert Museum

Described by him as “a thing apart from all other painting or drawing”, the portrait miniatures of Hilliard (1547-1619) and his sometime pupil Isaac Oliver (1565-1617) are not just a unique contribution to the evolution of British painting, but among the great works of European art. Hilliard was the first English artist to be “much admired”, a contemporary wrote, “amongst strangers”. Prized by Medicis, Hapsburgs and Bourbons, he was compared to Raphael. John Donne, homing in on the genius of his miniatures in comparison to enormous history paintings, wrote that “a hand, or eye/ By Hilliard drawn, is worth an history,/ By a worse painter made”.

The hand in a Hilliard is fractional, the eye practically subatomic. Naturally, this is what strikes first in this magnificent show, as you struggle to see how the miracle is achieved through the magnifying glass conveniently supplied. But enlargement turns out to explain nothing of the magic: the air of wayward distractedness in Sir Walter Raleigh’s brilliant blue eyes; the hopeful optimism in the teenage face of Henry, Prince of Wales, with his incipient moustache; the alarming steeliness of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, favourite of Elizabeth I.

Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester by Hilliard

The queen’s appearance itself, so often painted as little more than a jewelled diagram, bodies forth with far greater plausibility in these miniatures. Hilliard, 30 years a court painter, particularly captures the curious contours of her egg-shaped head, the cavernous eye sockets and protuberant lower lip. Isaac Oliver went further, showing a deep crease in the forehead, thinning hair and a greater protuberance as Gloriana lost her teeth.

Francis Bacon later Baron Verulam and Viscount St Alban by Hilliard

Sharp sight, close scrutiny; there is some irreducible connection between scale and observation in this art. Hilliard and Oliver are so much more acute than their contemporaries. It is not just that their portraits haven’t the usual stiffness of Elizabethan art, nor its superficial concern with power, but that they seem so probing in their contemplation.

Sir Francis Drake, veteran explorer, has weather-reddened cheeks and undeceived eyes. Francis Bacon, future philosopher and statesman, is already exhausted by his own midnight-oil precocity as a shrewd 17-year-old thinker. And if you did not know that Sir Philip Sidney’s sister Mary was herself a considerable writer, you might deduce it from her half-smiling face, quick with intelligent curiosity.

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, by Isaac Oliver, c. 1596. Photograph: Private Collection/ © Christie's, 2011.

The Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron and (some say) lover, appears in a staggering image by Isaac Oliver, far more revealing than any of the many other likenesses painted during his lifetime. The notorious love lock descends almost to his navel, the high quiff appears to be held aloft with something like sugared water, and his amused round eyes catch yours with an expression of almost unnerving confidence.

Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox and Duke of Richmond 1574-1624, The Fitzwilliam Museum

How these miniatures are made is the subject of a short film and an excellent display at the National Portrait Gallery. Bright as enamel, they are, in fact, painted with something like modern watercolour – crushed pigment bound with gum – using humble squirrel-hair brushes. Colossal photographic magnifications show almost imperceptible stipplings and shadings: the single suave line by which Hilliard dashes off an eyelid; Oliver’s gift for a graduated blush.

Anne of Denmark, National Portrait Gallery

A steady hand was the merest requirement. These artists had to get a likeness down in two or three sittings lasting not much more than an hour – like Holbein or Van Dyck – but on a piece of vellum no bigger than a playing card. And cards were the commonest form of support; a portrait of Elizabeth I, in this show, has the Queen of Hearts glued to the back. There is wit in the miniaturist’s art.

And it is evident in the face of Hilliard himself, with all his questioning vitality. Sixteenth-century self-portraits are so rare in England that perhaps only three are known: two in oils and this far greater miniature, in which the young painter announces himself as an aristocrat. Exeter-born, London-trained as a jeweller, Hilliard saw the works of Holbein in England and Clouet in France (Elizabeth had trouble getting him home), and still he seems to have sprung fully formed from nowhere.

Self-portrait aged 30, by Nicholas Hilliard. Photograph: Victoria & Albert Museum

Oliver has speed, humour, open affection. His terrific portrait of the Browne brothers shows a trio of likely lads entwined like The Three Graces for a lark. His new young wife looks back at the painter with an equal degree of warmth. He appears more modern, continental, broader of stroke, better at perspective. Hilliard is more austere, yet also profound.

Unknown Lady by Hilliard, The Fitzwilliam Museum

Hilliard wrote a treatise full of advice for fellow miniaturists. “Let your apparel be silk, such as sheddeth least dust or hairs.” Talk gently to keep your fidgety sitters (notably James I) from moving. Aim for the immediacy of a private encounter, and all “those lovely graces, witty smilings, and those stolen glances which suddenly like lightning pass”. For these images are unlike any other: intimate objects that may be kept in secret boxes or worn in lockets about the body, brought out for a moment and then hidden away; messages of love, to be passed from hand to hand.

Self-portrait by Isaac Oliver, National Portrait Gallery

And this is nowhere more explicit than in Hilliard’s famously mysterious portrait of 1588, known as Man Clasping a Hand from a Cloud. The identity of the eponymous gentleman, with his pale eyes and fine golden tendrils, has never been established. Perhaps something in his black satin doublet and elaborate hat, trimmed with intricate silver lace, might have given a clue in his day. But descending from the transparent circles of cloud above is another hand cuffed with equally complicated lace. It might be male or female; certainly it is as slim and graceful as his own.

Man Clasping Hand from a Cloud by Hilliard, 1588

If Hilliard’s art draws you straight into the private lives of Elizabethans, this painting goes closer still to the sitter’s heart (quite literally, if it was meant to hang there). The gentleman clasps the hand of his beloved, who is perhaps dead and gone, but still looking down upon him from the afterlife, protecting him, accompanying him wherever he goes – like the miniature itself, a masterpiece as condensed as a sonnet.

● Elizabethan Treasures: Miniatures By Hilliard and Oliver is at National Portrait Gallery, London, until 19 May

If Hilliard’s art draws you straight into the private lives of Elizabethans, this painting goes closer still to the sitter’s heart (quite literally, if it was meant to hang there). The gentleman clasps the hand of his beloved, who is perhaps dead and gone, but still looking down upon him from the afterlife, protecting him, accompanying him wherever he goes – like the miniature itself, a masterpiece as condensed as a sonnet.

● Elizabethan Treasures: Miniatures By Hilliard and Oliver is at National Portrait Gallery, London, until 19 May

Monday, 25 February 2019

Sunday, 24 February 2019

Stanley Donen RIP

By Richard Severo

The New York Times

23 February 2019

Stanley Donen, who directed Fred Astaire dancing on the ceiling, Gene Kelly singing in the rain and a host of other sparkling moments from some of Hollywood’s greatest musicals, died on Thursday in Manhattan. He was 94.

His son, Mark Donen, confirmed the death.

Stanley Donen brought a certain charm and elegance to the silver screen in the late 1940s through the 1950s, at a time when Hollywood was soaked in glamour and the big studio movies were polished to a sheen.

“For a time, Donen epitomized Hollywood style,” Tad Friend wrote in The New Yorker in 2003. Mr. Donen, he wrote, “made the world of champagne fountains and pillbox hats look enchanting, which is much harder than it sounds.”

23 February 2019

Stanley Donen, who directed Fred Astaire dancing on the ceiling, Gene Kelly singing in the rain and a host of other sparkling moments from some of Hollywood’s greatest musicals, died on Thursday in Manhattan. He was 94.

His son, Mark Donen, confirmed the death.

Stanley Donen brought a certain charm and elegance to the silver screen in the late 1940s through the 1950s, at a time when Hollywood was soaked in glamour and the big studio movies were polished to a sheen.

“For a time, Donen epitomized Hollywood style,” Tad Friend wrote in The New Yorker in 2003. Mr. Donen, he wrote, “made the world of champagne fountains and pillbox hats look enchanting, which is much harder than it sounds.”

Mr. Donen worked with some of the most illustrious figures of his era: from Astaire and Kelly to Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn. He also worked with Leonard Bernstein, the lyricist Alan Jay Lerner and the writing team of Comden and Green, not to mention Frank Sinatra and Elizabeth Taylor.

Mr. Donen’s filmography is studded with some of Hollywood’s most loved and admired musicals. “Royal Wedding” (1951), in which Astaire defied gravity, and “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952), in which Kelly defied the weather, were just two of his crowd-pleasers.

Among many others were the Leonard Bernstein-Betty Comden-Adolph Green collaboration “On the Town” (1949) — which, like “Singin’ in the Rain,” Mr. Donen co-directed with Kelly — as well as “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers” (1954), with Jane Powell; “Funny Face” (1957), with Hepburn and Astaire; and “Damn Yankees” (1958), with Tab Hunter and Gwen Verdon.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences acknowledged his mastery by honoring Mr. Donen in 1998 with a lifetime achievement award for “a body of work marked by grace, elegance, wit and visual innovation.” Many saw the award as Hollywood’s way of making amends because Mr. Donen had never been nominated for an Oscar, much less won one.

Mr. Donen also directed thrillers like “Charade,” wild comedies like “Bedazzled” and rueful romances like “Two for the Road.” But musicals were his specialty, and his fellow director Jean-Luc Godard — though it could be said that his French New Wave films borrowed virtually nothing from Mr. Donen’s work — spoke for many when he called Mr. Donen “the master of the musical.”

He began his career in Kelly’s shadow. The two first worked together in 1940, in the original Broadway production of Rodgers and Hart’s “Pal Joey.”

Mr. Donen, who had graduated from a South Carolina high school that June at the age of 16, was a member of the chorus; Kelly was the star. They were together again the next year on Broadway in “Best Foot Forward,” Kelly as choreographer and Mr. Donen as dancer. The film critic Andrew Sarris wrote in his book “The American Cinema” that Mr. Donen was “dismissed for a time as Gene Kelly’s invisible partner.”

But there was no dismissing the quality, or the impact, of his solo directorial debut, “Royal Wedding.” With a score by Lerner (who also wrote the screenplay) and Burton Lane, it starred Astaire as an American dancer who is in London to do a show with his sister (Powell) during the same period as the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip.

Astaire’s character falls in love with a dancer in his show, played by Sarah Churchill. One evening he comes home to his flat and, inspired by her photograph, begins to dance — first on the floor and then, in cheerful violation of the laws of physics, on the walls and ceiling.

Mr. Donen, who had graduated from a South Carolina high school that June at the age of 16, was a member of the chorus; Kelly was the star. They were together again the next year on Broadway in “Best Foot Forward,” Kelly as choreographer and Mr. Donen as dancer. The film critic Andrew Sarris wrote in his book “The American Cinema” that Mr. Donen was “dismissed for a time as Gene Kelly’s invisible partner.”

But there was no dismissing the quality, or the impact, of his solo directorial debut, “Royal Wedding.” With a score by Lerner (who also wrote the screenplay) and Burton Lane, it starred Astaire as an American dancer who is in London to do a show with his sister (Powell) during the same period as the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip.

Astaire’s character falls in love with a dancer in his show, played by Sarah Churchill. One evening he comes home to his flat and, inspired by her photograph, begins to dance — first on the floor and then, in cheerful violation of the laws of physics, on the walls and ceiling.

The sequence, famous in Hollywood lore, took place in a chamber that revolved depending on where weight was applied. Astaire called it the iron lung. (Both Astaire and Lerner took credit for coming up with the idea.)

In his book “Dancing on the Ceiling: Stanley Donen and His Movies” (1996), Stephen M. Silverman wrote that the room’s draperies were made of wood and the coat that Astaire took off was sewn to the chair where he left it, which in turn was screwed to the floor. The year after making “Royal Wedding,” for MGM, Mr. Donen teamed up again with Kelly for the same studio to make “Singin’ in the Rain,” widely regarded as one of the best movie musicals ever made.

Although they shared directing tasks throughout the movie — a story of the early days of talking pictures starring Kelly, Debbie Reynolds, Donald O’Connor and Jean Hagen, with a screenplay by Comden and Green and songs from the 1920s and 1930s — there was no question who was behind the camera when a thoroughly soaked Kelly bounded ecstatically down a back-lot street in a torrential downpour singing the title song, his dancing partner an umbrella that he ultimately thrust into the hands of a grateful passer-by. The critic Roger Ebert called it “probably the most joyous musical sequence ever filmed.”

Stanley Donen was born on April 13, 1924, in Columbia, S.C., the son of Mordecai Moses Donen, the manager of a chain store that sold midrange dresses, and the former Helen Cohen. He did not much like living in the South, where he often encountered anti-Semitism. “It was sleepy, it was awful, I hated growing up there and I couldn’t wait to get out,” he is quoted as saying in Mr. Silverman’s book.

As a boy he experimented with cameras his parents gave him. “The camera was like a constant companion,” he once said. “It allowed me to withdraw into myself.”

Mr. Donen took refuge in the movies, collecting and studying silent films. Not long after seeing Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in “Flying Down to Rio” (1933), their first screen pairing, he decided that he wanted to be a tap dancer.

His father spent summers at the home office of his company, in New York City, and a young Mr. Donen would accompany him. Although his parents were not at all sure they approved of his career path, they saw to it that while in New York he attended dance school. He also went to see many Broadway musicals.

Mr. Donen moved to New York as soon as he could after spending a semester at the University of South Carolina studying psychology, a subject he had taken up to please his father. He paid $15 a week as a lodger in a couple’s apartment on West 55th Street and landed a job in “Pal Joey.”

In 1942, Mr. Donen, not yet 19, went to Hollywood, where he was hired as a $65-a-week dancer at MGM and appeared in the movie version of “Best Foot Forward” (1943), which he also helped choreograph.

In 1944, Columbia Pictures borrowed both Mr. Donen and Kelly from MGM for “Cover Girl.” Though neither man received screen credit for it, they both contributed to the film’s choreography, with Mr. Donen handling the famous “Alter Ego” scene, a double-exposure number in which Kelly appears to be dancing with himself.

Their association continued in “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” (1949), which starred Frank Sinatra and Esther Williams as well as Kelly. The director was Busby Berkeley, but Mr. Donen and Kelly staged the musical numbers and also provided the story line.

“On the Town,” the acclaimed story of three sailors (Kelly, Sinatra and Jules Munshin) on leave in New York, with music by Leonard Bernstein, was the first of three films the two men directed together. Their final collaboration was “It’s Always Fair Weather” (1955).

Mr. Donen was again on his own in 1954 when he directed “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers,” starring Powell and Howard Keel and choreographed energetically by Michael Kidd.

Cyd Charisse, who worked with Mr. Donen in “Singin’ in the Rain” and “It’s Always Fair Weather,” called him “one of the few directors I worked for who could tell you exactly what he wanted.” Gregory Peck, whom Mr. Donen directed in “Arabesque” (1966), a drama of international intrigue, praised his “terrific instinct for communicating.”

Mr. Donen shifted his focus from musicals after moving to England in 1958. He won critical praise for the romantic comedy “Indiscreet” (1958), starring Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant; the Hitchcockian comic thriller “Charade” (1963), with Grant and Audrey Hepburn; the manic “Bedazzled” (1967), starring and written by Peter Cook and Dudley Moore; and “Two for the Road” (1967), a romantic comedy written by Frederic Raphael, which starred Hepburn and Albert Finney.

He had few artistic or financial triumphs after returning to the United States in 1975 to direct the problem-plagued Burt Reynolds-Liza Minnelli vehicle “Lucky Lady,” which failed at the box office and damaged his career. He made a modest comeback in 1978 with the parody “Movie Movie,” written by Larry Gelbart and Sheldon Keller, but never directed another movie after the indifferently received 1984 comedy “Blame It on Rio.”

He remained intermittently active into the 21st century. In 1993 he returned to Broadway to direct a theatrical version of the classic dance film “The Red Shoes.” But the production closed after five performances.

All five of Mr. Donen’s marriages — to the dancer and choreographer Jeanne Coyne, the actress Marion Marshall, Adelle Beatty, the actress Yvette Mimieux and Pamari Braden — ended in divorce. But he did not like living alone. For a time he had a cushion in his living room embroidered with the words “Eat, drink and remarry.”

The director and performer Elaine May was his companion of many years. He is survived by his sons, Mark and Joshua Donen, and a sister, Carla Davis. Another son, Peter, preceded him in death.

Mr. Donen made one of his last directorial efforts in 2002, directing Ms. May’s comedy “Adult Entertainment” off Broadway. The play tells the story of a group of pornography stars on a public-access channel who find that they have higher cultural aspirations but who know they will never achieve them, that they “won’t stop time” and “be the reward to civilization.” To Mr. Donen, such is the lot of most people in show business, or in any business.

“Here it is,” he told The New Yorker. “As an artist, I aspire to be as remarkable as Leonardo da Vinci. To be fantastic, astonishing, one of a kind. I will never get there. He’s the one who stopped time. I just did ‘Singin’ in the Rain.’ It’s pretty good, yes. It’s better than most, I know. But it still leaves you reaching up.”

Saturday, 23 February 2019

Peter Tork RIP

![[​IMG]](https://www.monkeeslivealmanac.com/uploads/7/8/9/5/7895731/3170255_orig.jpg)

By Harrison Smith

THe Washington Post

21 February 2019

Peter Tork, a blues and folk musician who became a teeny-bopper sensation as a member of the Monkees, the wisecracking, made-for-TV pop group that imitated and briefly outsold the Beatles, died Feb. 21. He was 77.

The death was announced by his official Facebook page, which did not say where or how he died. Mr. Tork was diagnosed with adenoid cystic carcinoma, a rare cancer affecting his tongue, in 2009.

If the Monkees were a manufactured version of the Beatles, a “prefab four” who auditioned for a rock-and-roll sitcom and were selected more for their long-haired good looks than their musical abilities, Mr. Tork was the group’s Ringo, its lovably goofy supporting player.

On television, he performed as the self-described “dummy” of the group, drawing on a persona he developed while working as a folk musician in Greenwich Village, where he flashed a confused smile whenever his stage banter fell flat. Off-screen, he embraced the Summer of Love, donning moccasins and love beads and declaring that “nonverbal, extrasensory communication is at hand” and that “dogmatism is leaving the scene.”

A versatile multi-instrumentalist, Mr. Tork mostly played bass and keyboard for the Monkees, in addition to singing lead on tracks including “Long Title: Do I Have to Do This All Over Again,” which he wrote for the group’s psychedelic 1968 movie, “Head,” and “Your Auntie Grizelda.”

At age 24, he was the band’s oldest member when “The Monkees” premiered on NBC in 1966. Not that it mattered: “The emotional age of all of us,” he told the New York Times that year, “is 13.”

Created by producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, “The Monkees” was designed to replicate the success of “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!,” director Richard Lester’s musical comedies about the Beatles.

The band featured Mr. Tork alongside Michael Nesmith, a singer-songwriter who played guitar, and former child actors Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones, who played the drums and sang lead, respectively. Like their British counterparts, the group had a fondness for mischief, resulting in high jinks involving a magical necklace, a monkey’s paw, high-seas pirates and Texas outlaws.

“The Monkees” ran for only two seasons but won an Emmy Award for outstanding comedy and spawned a frenzy of merchandising, record sales and world tours that became known as Monkeemania. In 1967, according to one report in The Washington Post, the Monkees sold 35 million albums — “twice as many as the Beatles and Rolling Stones combined” — on the strength of songs such as “Daydream Believer,” “I’m a Believer” and “Last Train to Clarksville,” which all rose to No. 1 on the Billboard record chart.

Almost all of their early material was penned by a stable of vaunted songwriters that included Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Neil Diamond, David Gates, Neil Sedaka, Jeff Barry, Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart. But while the band scored a total of six Top 10 songs and five Top 10 albums, they engendered as much critical scorn as commercial success. In one typical review, music critic Richard Goldstein declared, “The Monkees are as unoriginal as anything yet thrust upon us in the name of popular music.”

Detractors pointed to the fact that the band, at least initially, existed only in name. While the Monkees appeared on the cover of their debut album and were shown performing on TV, their instruments were actually unplugged. The songs were mostly done by session musicians — much to the shock of Mr. Tork, who recalled walking into the recording studio in 1966 to help with the group’s self-titled debut.

He was “mortified,” he later told CBS News, to find that music producer Don Kirshner, dubbed “the man with the golden ear,” didn’t want him around. “They were doing ‘Clarksville,’ and I wrote a counterpoint. I had studied music,” Mr. Tork said. “And I brought it to them, and they said: ‘No, no, Peter, you don’t understand. This is the record. It’s all done. We don’t need you.’ ”

After the release of the band’s second album, “More of the Monkees” (1967), Mr. Tork and his bandmates wrested control of the recording process and wrote and performed most of the songs on records including “Headquarters” (1967) and “Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.” (1967).

They also started touring, playing to sold-out stadium crowds and backed by opening acts that briefly included guitarist Jimi Hendrix. But as Mr. Tork’s musical ambitions grew, leading him to envision the Monkees as a genuinely great group of rockers, he began to clash with bandmates who saw the Monkees as more of a novelty act.

He left the group soon after the release of “Head” (1968), a satirical, nearly plot-free film flop that featured a screenplay co-written by actor Jack Nicholson. Mr. Tork seemed to have taken his cue from musician Frank Zappa, who made a cameo in the movie, telling Jones’s character that the Monkees “should spend more time” on their music “because the youth of America depends on you that show the way.”

For much of the 1970s, Mr. Tork struggled to find his own way. He formed an unsuccessful band called Release, was imprisoned for several months in 1972 after being caught with “$3 worth of hashish in my pocket,” and worked as a high school teacher and “singing waiter” as his Monkees wealth dried up. He also said he struggled with alcohol addiction — “I was awful when I was drinking, snarling at people,” he told the Daily Mail — before quitting alcohol in the early 1980s.

By then, television reruns and album reissues had fueled a resurgence of interest in the Monkees, and Mr. Tork had come around to what he described as the essential nature of the music group, which he joined for major reunion tours about once each decade, beginning in the mid-1980s, in addition to performing as a solo artist.

![[​IMG]](https://i.imgur.com/RwtSogz.jpg)

“This is not a band. It’s an entertainment operation whose function is Monkee music,” he told Britain’s Telegraph newspaper during a Monkees tour in 2016. “It took me a while to get to grips with that but what great music it turned out to be! And what a wild and wonderful trip it has taken us on!”

He was born Peter Halsten Thorkelson in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 13, 1942. His mother was a homemaker, and his father — an Army officer who served in the military government in Berlin after World War II — was an economics professor who joined the University of Connecticut in 1950, leading the family to settle in the town of Mansfield.

His parents collected folk records and bought him a guitar and banjo when he was a boy. Peter went on to take piano lessons and studied French horn at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn., where he reportedly flunked out twice before settling in New York. At coffee shops and makeshift folk music venues, he performed with the shortened last name Tork, which had been emblazoned on one of his father’s hand-me-down sweatshirts, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Mr. Tork played with guitarist Stephen Stills before moving to Long Beach, Calif., in 1965. Stills moved west as well and auditioned for “The Monkees” after the show’s producers placed an advertisement in Variety calling for “4 Insane Boys, Ages 17-21.”

Peter Tork, a blues and folk musician who became a teeny-bopper sensation as a member of the Monkees, the wisecracking, made-for-TV pop group that imitated and briefly outsold the Beatles, died Feb. 21. He was 77.

The death was announced by his official Facebook page, which did not say where or how he died. Mr. Tork was diagnosed with adenoid cystic carcinoma, a rare cancer affecting his tongue, in 2009.

If the Monkees were a manufactured version of the Beatles, a “prefab four” who auditioned for a rock-and-roll sitcom and were selected more for their long-haired good looks than their musical abilities, Mr. Tork was the group’s Ringo, its lovably goofy supporting player.

On television, he performed as the self-described “dummy” of the group, drawing on a persona he developed while working as a folk musician in Greenwich Village, where he flashed a confused smile whenever his stage banter fell flat. Off-screen, he embraced the Summer of Love, donning moccasins and love beads and declaring that “nonverbal, extrasensory communication is at hand” and that “dogmatism is leaving the scene.”

A versatile multi-instrumentalist, Mr. Tork mostly played bass and keyboard for the Monkees, in addition to singing lead on tracks including “Long Title: Do I Have to Do This All Over Again,” which he wrote for the group’s psychedelic 1968 movie, “Head,” and “Your Auntie Grizelda.”

At age 24, he was the band’s oldest member when “The Monkees” premiered on NBC in 1966. Not that it mattered: “The emotional age of all of us,” he told the New York Times that year, “is 13.”

Created by producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, “The Monkees” was designed to replicate the success of “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!,” director Richard Lester’s musical comedies about the Beatles.

The band featured Mr. Tork alongside Michael Nesmith, a singer-songwriter who played guitar, and former child actors Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones, who played the drums and sang lead, respectively. Like their British counterparts, the group had a fondness for mischief, resulting in high jinks involving a magical necklace, a monkey’s paw, high-seas pirates and Texas outlaws.

“The Monkees” ran for only two seasons but won an Emmy Award for outstanding comedy and spawned a frenzy of merchandising, record sales and world tours that became known as Monkeemania. In 1967, according to one report in The Washington Post, the Monkees sold 35 million albums — “twice as many as the Beatles and Rolling Stones combined” — on the strength of songs such as “Daydream Believer,” “I’m a Believer” and “Last Train to Clarksville,” which all rose to No. 1 on the Billboard record chart.

Almost all of their early material was penned by a stable of vaunted songwriters that included Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Neil Diamond, David Gates, Neil Sedaka, Jeff Barry, Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart. But while the band scored a total of six Top 10 songs and five Top 10 albums, they engendered as much critical scorn as commercial success. In one typical review, music critic Richard Goldstein declared, “The Monkees are as unoriginal as anything yet thrust upon us in the name of popular music.”

Detractors pointed to the fact that the band, at least initially, existed only in name. While the Monkees appeared on the cover of their debut album and were shown performing on TV, their instruments were actually unplugged. The songs were mostly done by session musicians — much to the shock of Mr. Tork, who recalled walking into the recording studio in 1966 to help with the group’s self-titled debut.

He was “mortified,” he later told CBS News, to find that music producer Don Kirshner, dubbed “the man with the golden ear,” didn’t want him around. “They were doing ‘Clarksville,’ and I wrote a counterpoint. I had studied music,” Mr. Tork said. “And I brought it to them, and they said: ‘No, no, Peter, you don’t understand. This is the record. It’s all done. We don’t need you.’ ”

After the release of the band’s second album, “More of the Monkees” (1967), Mr. Tork and his bandmates wrested control of the recording process and wrote and performed most of the songs on records including “Headquarters” (1967) and “Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.” (1967).

They also started touring, playing to sold-out stadium crowds and backed by opening acts that briefly included guitarist Jimi Hendrix. But as Mr. Tork’s musical ambitions grew, leading him to envision the Monkees as a genuinely great group of rockers, he began to clash with bandmates who saw the Monkees as more of a novelty act.

He left the group soon after the release of “Head” (1968), a satirical, nearly plot-free film flop that featured a screenplay co-written by actor Jack Nicholson. Mr. Tork seemed to have taken his cue from musician Frank Zappa, who made a cameo in the movie, telling Jones’s character that the Monkees “should spend more time” on their music “because the youth of America depends on you that show the way.”

For much of the 1970s, Mr. Tork struggled to find his own way. He formed an unsuccessful band called Release, was imprisoned for several months in 1972 after being caught with “$3 worth of hashish in my pocket,” and worked as a high school teacher and “singing waiter” as his Monkees wealth dried up. He also said he struggled with alcohol addiction — “I was awful when I was drinking, snarling at people,” he told the Daily Mail — before quitting alcohol in the early 1980s.

By then, television reruns and album reissues had fueled a resurgence of interest in the Monkees, and Mr. Tork had come around to what he described as the essential nature of the music group, which he joined for major reunion tours about once each decade, beginning in the mid-1980s, in addition to performing as a solo artist.

![[​IMG]](https://i.imgur.com/RwtSogz.jpg)

“This is not a band. It’s an entertainment operation whose function is Monkee music,” he told Britain’s Telegraph newspaper during a Monkees tour in 2016. “It took me a while to get to grips with that but what great music it turned out to be! And what a wild and wonderful trip it has taken us on!”

He was born Peter Halsten Thorkelson in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 13, 1942. His mother was a homemaker, and his father — an Army officer who served in the military government in Berlin after World War II — was an economics professor who joined the University of Connecticut in 1950, leading the family to settle in the town of Mansfield.

His parents collected folk records and bought him a guitar and banjo when he was a boy. Peter went on to take piano lessons and studied French horn at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn., where he reportedly flunked out twice before settling in New York. At coffee shops and makeshift folk music venues, he performed with the shortened last name Tork, which had been emblazoned on one of his father’s hand-me-down sweatshirts, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Mr. Tork played with guitarist Stephen Stills before moving to Long Beach, Calif., in 1965. Stills moved west as well and auditioned for “The Monkees” after the show’s producers placed an advertisement in Variety calling for “4 Insane Boys, Ages 17-21.”

When Stills didn’t get the part — purportedly on account of his bad teeth — he suggested that Mr. Tork audition. “I went, ‘Yeah, sure, thanks for the call,’ and hung up,” Mr. Tork later told the Los Angeles Times. “Then he called me a few days later,” finally persuading Mr. Tork to try out.

He later appeared in episodes of television shows such as “Boy Meets World,” playing Topanga’s guitar-strumming father, and in recent years performed with a band called Shoe Suede Blues. Mr. Tork also released a well-received 1994 solo album, “Stranger Things Have Happened,” and partnered with folk singer James Lee Stanley for several records.

Mr. Tork’s marriages to Jody Babb, Reine Stewart and Barbara Iannoli ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife, Pamela Grapes; a daughter, Hallie, from his second marriage; a son, Ivan, from his third marriage; a daughter, Erica, from a relationship with Tammy Sustek; a brother; and a sister.

Many of the Monkees reunion tours were conducted without Nesmith, who inherited a fortune from his mother, the inventor of Liquid Paper, and worked as a country-rock musician, songwriter and producer after the band first split up. Nesmith returned to performances after the death of Jones, the Monkees’ singer, in 2012, which helped spur a 50th anniversary reunion tour and album, “Good Times!,” four years later.

And while the Monkees were dogged by reports of squabbling and frequent tensions — Mr. Tork was once head-butted by Jones, and he said he dropped out of a 2001 tour because he had a “meltdown” and “behaved inappropriately” — Mr. Tork insisted that they were at their best when they were together. Their musical chemistry was special, he said, even if it was the result of a few producers looking to cast handsome men for a television show.

“I refute any claims that any four guys could’ve done what we did,” he told Guitar World in 2013. “There was a magic to that collection. We couldn’t have chosen each other. It wouldn’t have flown. But under the circumstances, they got the right guys.”

Friday, 22 February 2019

Wednesday night's set lists at The Habit, York

Autumn Leaves

Dedicated Follower Of Fashion

Da Elderly: -

Oh Lonesome Me

Never Let Her Slip Away

The Elderly Brothers with Tim Williamson (harmonica): -

Bring It On Home To Me

Mailman Bring Me No More Blues

Medley: High Heel Sneakers/It's All Over Now

It turned out to be one of those really special Habit open mic nights. Initially quiet, but heaving by 9:30. What an eclectic mix of music and styles!

Having encouraged local picker Dave over the last few weeks, we finally persuaded him to get up and play - he surprised us with Stephen Stills' Manassas song Johnny's Garden and Graham Nash's Prison Song from the album Wild Tales 1974.

Harmonica maestro Tim was supported by our host Simon on guitar and they played superb versions of the blues standard Sitting On Top Of The World and the Jerry Leiber/Mike Stoller classic Kansas City, with everyone joining in on the "Hey hey hey hey" and "Bye bye bye bye" parts.

There was a Viking invasion at about 10:30 (only in York! There's a festival on at the moment). One sang acapella.....the oldest known song in old Welsh. Another brute sang acapella too.....a song with the refrain Troll Hammering.

We had an unexpected visit from our previous host Dave who sang duets with current host Simon (see picture above): a self-penned tune Marianas and a couple of standards, Summertime and Georgia On My Mind. Excellent stuff!

The Elderly Brothers closed out the show aided and abetted by Tim on harmonica. As soon as we finished there we cries for "more" and we continued unplugged for the best part of an hour.

What a night!!!

Thursday, 21 February 2019

Paddy McAloon: Creativity from enforced idleness 2019

Prefab Sprout’s Paddy McAloon: ‘Like Gandalf on his way to work in the House of Lords’

Paddy McAloon on his unsensous name, intelligent songs and being a ‘health disaster’

Tony Clayton-Lea

The Irish Times

Saturday 26 Jan 2019

In the way that heavy-duty tides, unusually high sea levels and strong winds can bring about the reappearance of once-hidden tracts of beach, Paddy McAloon has been seen again. Admittedly the Prefab Sprout songwriter and singer isn’t easy to ignore – he has for some time now dressed like Gandalf on his way to work in the House of Lords: long, grey beard and hair tops a figure in a smart suit, a hand grasping a cane more for stability than display. There are reasons, however, why Durham-based McAloon makes irregular appearances, and they are nothing to do with the weather.

“I have Ménière’s disease, and I’ve had problems for over 12 years, but in October 2017 it all descended on me again. In January last year, I got up one day and I couldn’t keep my balance. I fell over, I felt incredibly sick, had to lie still on the floor, and to make it worse it was in the middle of a record shop in Newcastle. I couldn’t move.”

A disorder of the inner ear characterised by vertigo, tinnitus and hearing loss, Ménière’s disease – which has no known cure – has caused McAloon to retreat from public life. By this point, he says, he has pragmatically chosen to accept that unless matters radically change (which he feels they won’t), he will never perform a gig in front of an audience again.

“To play live, where you have volume involved, and amplification of volume, is courting disaster, so that’s really gone. I can’t say that I miss the gigs, but I don’t like the option being taken away from me.”

There is a sliver of resignation in his voice, and also regret, when he says that the best he can hope for is “singing into a little video camera at home, but even then the sound of an acoustic guitar is offensive to my ears. I can pick out chords and melodies on a small keyboard, so I can technically write, but it’s not what it was.”

Detached retinas

To make matters worse McAloon (who cheerfully refers to himself as “Mr Health Disaster”) also has detached retinas. Oddly, the end result of the early onset of failing eyesight is the reason we’re talking: the reissue of his only solo album, I Trawl the Megahertz, which was first released in 2003. Something of an anomaly in the Prefab Sprout catalogue, in that it is virtually all instrumental, it unfolds with extended orchestrated sections not too far removed from Ravel or Debussy. The album, now reissued under the Prefab Sprout title, was inspired by McAloon’s “enforced idleness” of lying on his back and listening to people talking.

“I couldn’t read because of the medication, which entailed putting drops in my eyes,” he reveals, “and so I found refuge in audiobooks. Through those I thought it would be good to create a piece of music that was almost in the background, music that would drift in and out, with some spoken word.”

He contends it was not out of ego but concern for fans that I Trawl the Megahertz was initially issued as a solo album. “I didn’t want any criticism of it to be directed at the other members of the band by some people moaning about there being no hit songs, or that I sing on just one track – all of the normal complaints a fan might make about someone whose work you like, yet they’re doing something different.”

More than marketing

In the intervening years, McAloon reconsidered various pros and cons and now places the album alongside the likes of Jordan: The Comeback, Steve McQueen and, he teases, “lots of unreleased material that isn’t like what we were when we first started. In other words, I stared down my own objections. Yes, having I Trawl the Megahertz released as Prefab Sprout sounds crass from a branding or marketing point of view, but ultimately I wanted to reinstate an album that to all but the avid fans had virtually disappeared.”

The mention by McAloon of unreleased material is pivotal to his stature of not only one of contemporary music’s most elegant pop songwriters but also his almost fabled status as the writer of many hundreds of as yet unissued songs and albums. Is his work rate exaggerated?

“I tend to downplay it in interviews because it just adds fuel to the fire,” he replies. “The perception is that I’m just sitting on them and why aren’t I doing anything with them? Sometimes I put myself in the position of a fan, and wonder if I’m having a laugh by saying I’ve got so much unreleased material!”

We have a duty to ask – does he? “How many, is that what you’re asking? You can work it out by doing the maths – if you write three albums a year, approximately, and you’ve been doing that for 30 years, then that’s where we are. Most of it is in metal or plastic boxes with labels on them, and they are usually titled by the year or the project. If a songwriter or musician doesn’t play gigs, then they have an awful lot of time to fill in.”

Saturday 26 Jan 2019

In the way that heavy-duty tides, unusually high sea levels and strong winds can bring about the reappearance of once-hidden tracts of beach, Paddy McAloon has been seen again. Admittedly the Prefab Sprout songwriter and singer isn’t easy to ignore – he has for some time now dressed like Gandalf on his way to work in the House of Lords: long, grey beard and hair tops a figure in a smart suit, a hand grasping a cane more for stability than display. There are reasons, however, why Durham-based McAloon makes irregular appearances, and they are nothing to do with the weather.

“I have Ménière’s disease, and I’ve had problems for over 12 years, but in October 2017 it all descended on me again. In January last year, I got up one day and I couldn’t keep my balance. I fell over, I felt incredibly sick, had to lie still on the floor, and to make it worse it was in the middle of a record shop in Newcastle. I couldn’t move.”

A disorder of the inner ear characterised by vertigo, tinnitus and hearing loss, Ménière’s disease – which has no known cure – has caused McAloon to retreat from public life. By this point, he says, he has pragmatically chosen to accept that unless matters radically change (which he feels they won’t), he will never perform a gig in front of an audience again.

“To play live, where you have volume involved, and amplification of volume, is courting disaster, so that’s really gone. I can’t say that I miss the gigs, but I don’t like the option being taken away from me.”

There is a sliver of resignation in his voice, and also regret, when he says that the best he can hope for is “singing into a little video camera at home, but even then the sound of an acoustic guitar is offensive to my ears. I can pick out chords and melodies on a small keyboard, so I can technically write, but it’s not what it was.”

Detached retinas

To make matters worse McAloon (who cheerfully refers to himself as “Mr Health Disaster”) also has detached retinas. Oddly, the end result of the early onset of failing eyesight is the reason we’re talking: the reissue of his only solo album, I Trawl the Megahertz, which was first released in 2003. Something of an anomaly in the Prefab Sprout catalogue, in that it is virtually all instrumental, it unfolds with extended orchestrated sections not too far removed from Ravel or Debussy. The album, now reissued under the Prefab Sprout title, was inspired by McAloon’s “enforced idleness” of lying on his back and listening to people talking.

“I couldn’t read because of the medication, which entailed putting drops in my eyes,” he reveals, “and so I found refuge in audiobooks. Through those I thought it would be good to create a piece of music that was almost in the background, music that would drift in and out, with some spoken word.”

He contends it was not out of ego but concern for fans that I Trawl the Megahertz was initially issued as a solo album. “I didn’t want any criticism of it to be directed at the other members of the band by some people moaning about there being no hit songs, or that I sing on just one track – all of the normal complaints a fan might make about someone whose work you like, yet they’re doing something different.”

More than marketing

In the intervening years, McAloon reconsidered various pros and cons and now places the album alongside the likes of Jordan: The Comeback, Steve McQueen and, he teases, “lots of unreleased material that isn’t like what we were when we first started. In other words, I stared down my own objections. Yes, having I Trawl the Megahertz released as Prefab Sprout sounds crass from a branding or marketing point of view, but ultimately I wanted to reinstate an album that to all but the avid fans had virtually disappeared.”

The mention by McAloon of unreleased material is pivotal to his stature of not only one of contemporary music’s most elegant pop songwriters but also his almost fabled status as the writer of many hundreds of as yet unissued songs and albums. Is his work rate exaggerated?

“I tend to downplay it in interviews because it just adds fuel to the fire,” he replies. “The perception is that I’m just sitting on them and why aren’t I doing anything with them? Sometimes I put myself in the position of a fan, and wonder if I’m having a laugh by saying I’ve got so much unreleased material!”

We have a duty to ask – does he? “How many, is that what you’re asking? You can work it out by doing the maths – if you write three albums a year, approximately, and you’ve been doing that for 30 years, then that’s where we are. Most of it is in metal or plastic boxes with labels on them, and they are usually titled by the year or the project. If a songwriter or musician doesn’t play gigs, then they have an awful lot of time to fill in.”

Next album

On the boil is a batch of new songs for a forthcoming Spike Lee movie (Chasing Invisible Starlight, based on the children’s story written by Lee’s younger brother, Cinque), Pandora 63 (“about the Kennedy assassination”), and “a new project, a bunch of songs, that I plan to send to Trevor Horn. ” The more (or less) immediate future sees the release this September of a new Prefab Sprout album, Femmes Mythologiques.

It is, asserts McAloon, “a collection of reasonably short pop songs about women: Eve, Helen of Troy, Cleopatra, Queen of Sheba. I’m not selling it very well, am I? What the hell – it’s very tuneful, and the choruses are big. The whole idea of it is the distance between what we hear about people and how far removed they were from what we say about them. It’s a home recording, not a big, polished million-pound studio production, but it’s got heart.”

McAloon’s restraint is par for the course and is perhaps tempered by the great leveller that is a long-term illness. Never one to exaggerate matters, his focus and ambition (which seem endless) are balanced by the scope of his work (ditto). It helped, perhaps, that he didn’t play the pop music game very well.

He bursts out laughing. “I should have chosen a more sensuous name, for starters, but I wasn’t a strategist, a careerist – none of us was. Mostly the songs just try to be intelligent, funny, avoid cliches.” He has been saying this more often, he admits, “but on a Prefab Sprout record you won’t find anything that puts down a woman.” Even back in the day, he suggests, that seemed terribly old-fashioned if not wholly unnecessary.

“Did I idealise love? Yes, but that’s common enough in pop music. Did we have shiny, glossy pop songs? Yes, but that’s the aesthetic I like, a personal taste that has nothing to do with the times. Personally speaking I think we got by pretty well.”

I Trawl the Megahertz is released Friday, February 1st, through Sony Legacy. Femmes Mythologiques is scheduled for release in September

TOP 5 PREFAB SPROUT SONGS

Cruel (Swoon, 1984)

From the debut album. Cruel establishes McAloon’s long-standing idealisation of romance. His default setting, surely? “I’m a liberal guy, too cool for the macho ache … ”

Desire As (Steve McQueen, 1985)

Prefab Sprout’s follow-up album made them unlikely pop stars, but songs such as Desire As highlighted an unconventional trajectory with questions such as “Is it true you always see desire as a sylph-figured creature who changes her mind?”

Electric Guitars (Andromeda Heights, 1997)*

An ironic, wry take on pop stardom, the lyrics deliver a wish list surplus to requirements: “Riots in airports, everywhere that we go. Mascara meltdown, hysteria a-go-go ... ”

Last of the Great Romantics (Let’s Change the World with Music, 2009)*

McAloon once again delivers lyrics that, although playful, mask a broken heart. “Here comes the last of the great romantics, feet planted wide, defying the tide. Come on, Gatsby, stand aside.”

The Old Magician (Crimson/Red, 2013)*

The most recent Prefab Sprout album presents McAloon in mischievous form, with The Old Magician a wonderful sleight-of-hand self-reveal. “The old magician takes the stage, his act does not improve with age. Observe the shabby hat and gloves, the tired act that no one loves, there was a time he produced doves.”

* Not even close. The other two are but still wouldn't make my top five...

Tuesday, 19 February 2019

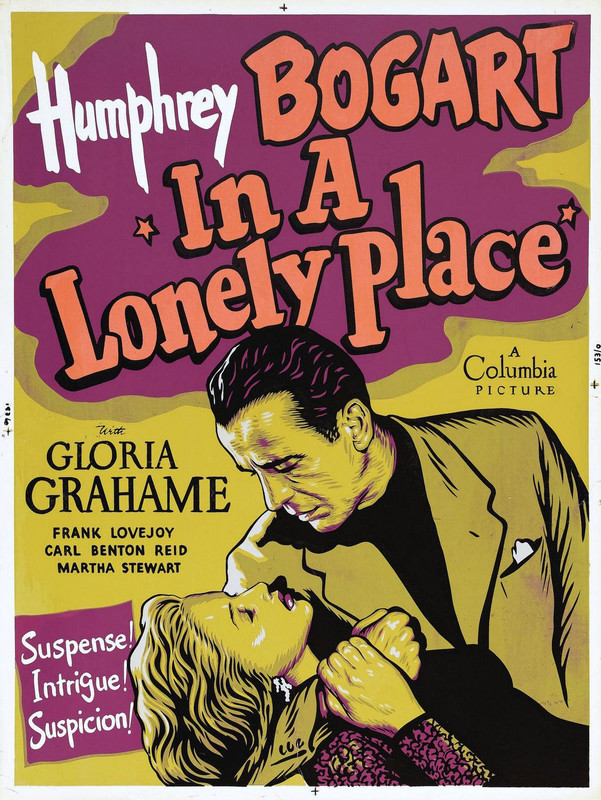

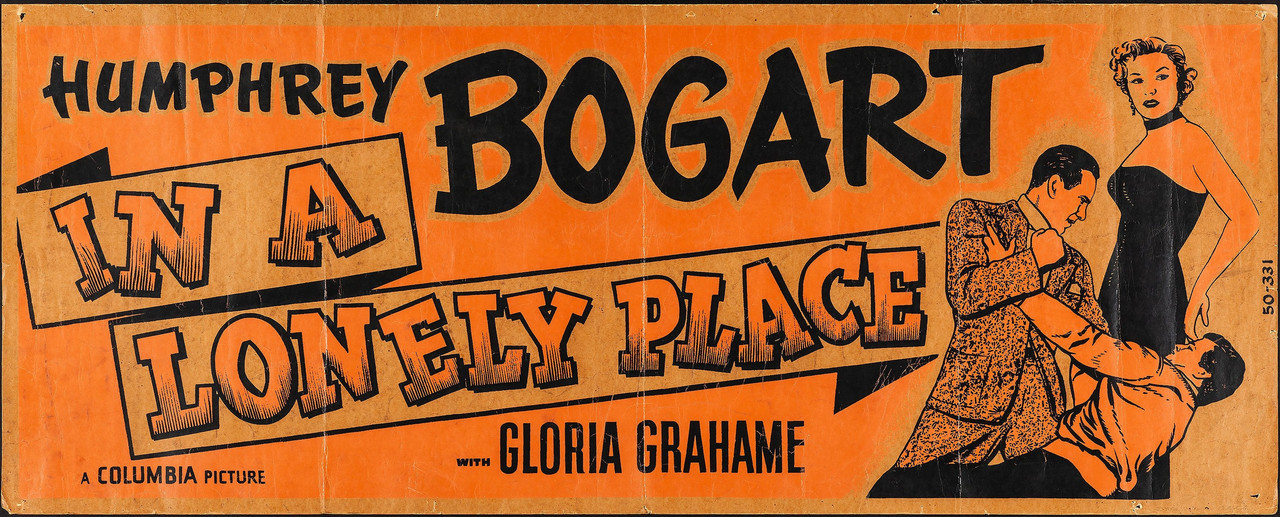

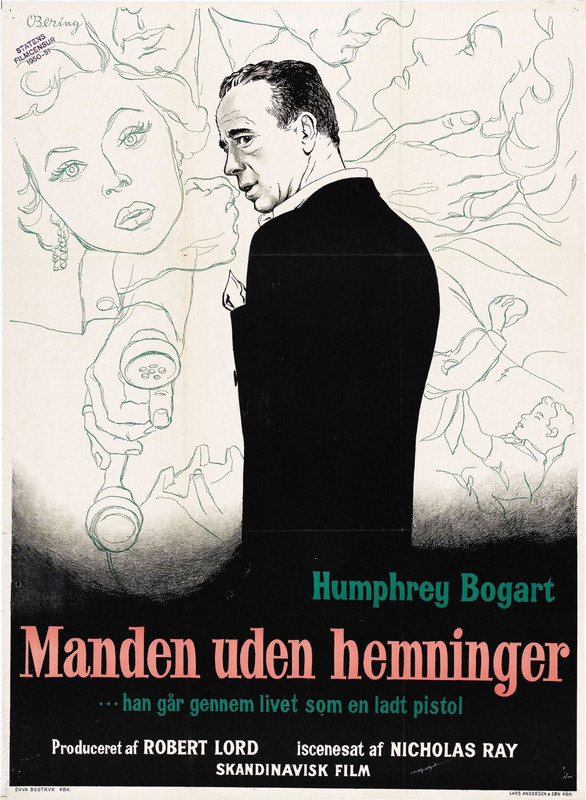

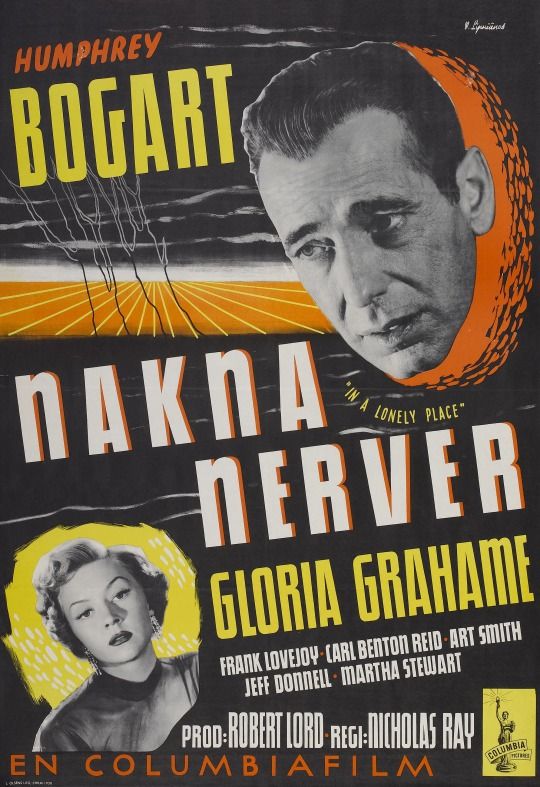

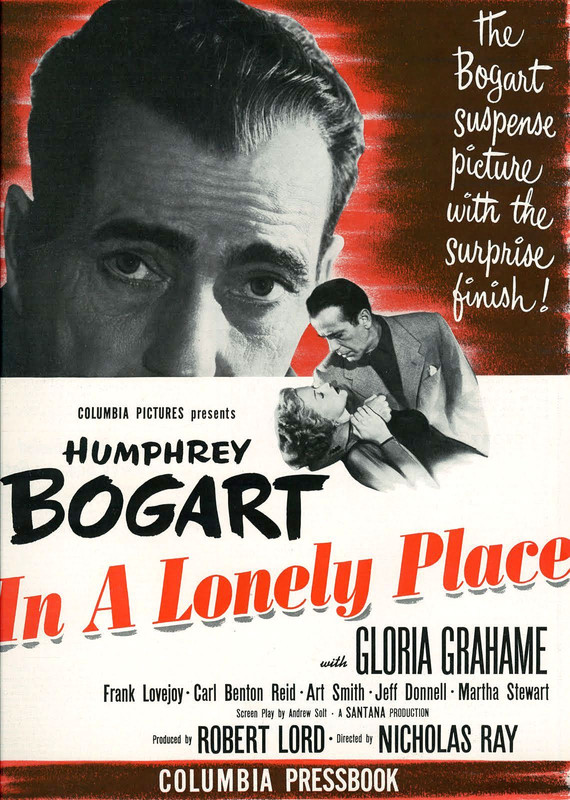

Film Noir Posters #17: In a Lonely Place (Ray, 1950)

My money's on the first poster (though it looks suspiciously modern in terms of the colour palette) and the Danish one. Not sure about Bogart's red lips on the Belgian poster, though...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)