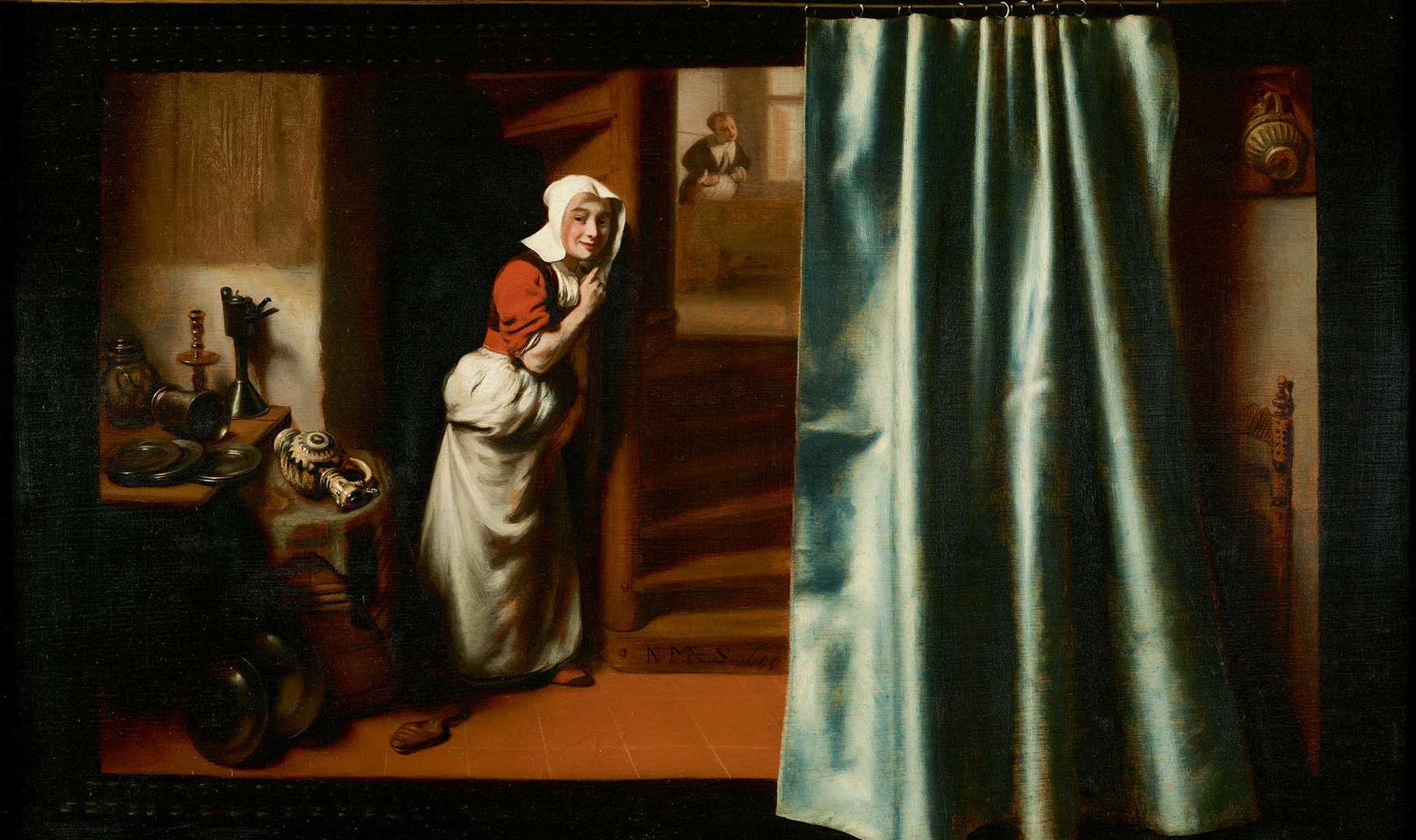

The Idle Servant, 1655

National Gallery, London

This quietly captivating exhibition reveals the depths of the Dutch Golden Age artist whose paintings are as rich in hidden drama as any theatre

Jonathan Jones

The Guardian

Fri 21 Feb 2020

The young woman painted by Nicolaes Maes in the 1650s, resting her elbow on a cushion on a window ledge while she meditatively cradles her chin in her hand, looks like she is independently reaching the same conclusion as René Descartes just a few years earlier: “I think, therefore I am.” Maes’s masterpiece Girl at a Window shows her surrounded by solid things. A wooden window covering has been flung open to show its planks to us in perspective. Bright apricots bulge over decaying plaster and brick. And yet, as the girl contemplates the physical world, a black void opens behind her. It is the cavern of consciousness in which all she can be sure of is cogito ergo sum.

Fri 21 Feb 2020

The young woman painted by Nicolaes Maes in the 1650s, resting her elbow on a cushion on a window ledge while she meditatively cradles her chin in her hand, looks like she is independently reaching the same conclusion as René Descartes just a few years earlier: “I think, therefore I am.” Maes’s masterpiece Girl at a Window shows her surrounded by solid things. A wooden window covering has been flung open to show its planks to us in perspective. Bright apricots bulge over decaying plaster and brick. And yet, as the girl contemplates the physical world, a black void opens behind her. It is the cavern of consciousness in which all she can be sure of is cogito ergo sum.

Girl at a Window, 1653-5

Maes was a pioneer of one of the world’s most beloved art styles – the humble realism of the Dutch Golden Age. The paintings in this quietly captivating exhibition lay down elements that his contemporary, Johannes Vermeer, would refine – women working in rooms, domestic mysteries, secret glances. He pulls back the curtain on a private realm. In one of a series of variations on the image of an eavesdropper smiling complicitly at us while she listens in on household secrets, this is literally true – there’s a curtain rail across the front of the picture with a green silk curtain partly pulled back to half-reveal a domestic row. The ordinary middle-class Dutch home, suggests Maes, is as rich in hidden drama as any theatre.

The Eavesdropper, 1656

By the 1670s Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch would take this art of everyday intrigue to exquisite heights of luminous detail but Maes is mapping new territory. Which brings us to his maps. In almost every one of his “genre” scenes – as paintings of day-to-day life were dismissively called by traditional connoisseurs – there’s a detailed map. Most of these wall decorations display the proud geography of the Netherlands, including its fragile coastline won from the North Sea. These omnipresent maps are analogies for Maes’s own art. He’s discovering interior worlds just as cartographers chart the outer world.

A Young Girl Threading a Needle, 1657

Like a map with regions marked Here Be Monsters, his precise recordings of Dutch homes have corners of mystery. In another version of his hit theme The Eavesdropper, a woman stands at the bottom of a spiral staircase with her finger to her lips, looking at you, urging quiet. To her left is a map, half-visible in muted daylight. She casts her shadow on the wall above a sleeping cat. Below her, on the other side of the stairs, lovers have been caught at it in the cellar, revealed by a servant’s lantern.

The Eavesdropper, 1655

This basement scandal looks like a little Rembrandt, all reds and yellows in the enveloping dark. That’s no coincidence. Maes was Rembrandt’s pupil. The trouble was, he – like Rembrandt’s other students – couldn’t come near his teacher in mysticising the Bible or portraying profundity. Maes’s An Old Woman Dozing is a banal version of Rembrandt’s Mother. His religious scenes are dreary – except the Adoration of the Shepherds, where he gets fascinated by the ruinous stable.

The Account Keeper, 1655

This exhibition shows Maes overcoming the crushing influence of Rembrandt by mainlining reality. It was the scientific revolution, after all – and the age of Dutch global commerce. The Account Keeper shows a woman asleep at her ledger. Above her hangs a map of the world. Is she doing the books for a merchant house with interests in Mughal India and Japan? The big houses Maes paints are surely those of just such merchants. His sharply lifelike portraits include that of Jan de Reus, a director of the Dutch East India Company.

The Old Lacemaker, 1656

It might be tempting to pigeonhole Maes as a coarse materialist who gave the Dutch elite what they wanted. But this exhibition reveals his depths. His paintings of everyday life are little novels or silent films. They take us into houses where everyone is spying on everyone else. Far from complacent celebrations of Dutch capitalism, these interiors are haunted. The Eavesdropper pauses at the bottom of the stairs. Above her those steps spiral into uncertainty. She’s caught between mind and world, listening in the dark. I spy, therefore I am.

•Nicolaes Maes: Dutch Master of the Golden Age is at the National Gallery, London, from 22 February to 31 May.

No comments:

Post a Comment