The Emerald Forest

Interview

John Boorman: 'You think the holy grail is lost? No. I have it on my piano

The director of classic Hollywood films including Excalibur, Point Blank and Deliverance lives alone in a giant house in rural Ireland. He talks about his career, growing old – and his obsession with the trees in his garden

XanBrooks

The Guardian

13 Feb 2020

Last summer, John Boorman embarked on what may prove to be his final film production. The location was the garden of his big house in Ireland. The cast were the towering trees that stand around it. During the 11-minute span of Tree Poems, Boorman tells us about the sycamore, the willow and the monkey puzzle he used to drape with Christmas lights every year. The director comes shuffling up the gravel drive, leaning on his stick, an old man among giants. When he turns back towards home, he vanishes from the frame.

Death, he admits, has been on his mind lately. Dead friends and forgotten films; successes and regrets. He turned 87 a few weeks ago, so it is small wonder he spends most of his time walking in nature and peering hard into the rear-view mirror. “I’ve been very fortunate in my life,” he says. “But there’s always the nagging sense that I could have made more, I could have done more. And that’s what sometimes keeps me up at night.”

The director has just written a book, Conclusions, in an attempt to exorcise these ghosts, or at least direct them towards some higher purpose. He wanted to write something that was part memoir, part instruction manual; a series of observations and life lessons. Except he now worries he didn’t quite bring it off, he says. The book is too scattershot and inconclusive. He jokes that he ought to have called it Confusions instead.

13 Feb 2020

Last summer, John Boorman embarked on what may prove to be his final film production. The location was the garden of his big house in Ireland. The cast were the towering trees that stand around it. During the 11-minute span of Tree Poems, Boorman tells us about the sycamore, the willow and the monkey puzzle he used to drape with Christmas lights every year. The director comes shuffling up the gravel drive, leaning on his stick, an old man among giants. When he turns back towards home, he vanishes from the frame.

Death, he admits, has been on his mind lately. Dead friends and forgotten films; successes and regrets. He turned 87 a few weeks ago, so it is small wonder he spends most of his time walking in nature and peering hard into the rear-view mirror. “I’ve been very fortunate in my life,” he says. “But there’s always the nagging sense that I could have made more, I could have done more. And that’s what sometimes keeps me up at night.”

The director has just written a book, Conclusions, in an attempt to exorcise these ghosts, or at least direct them towards some higher purpose. He wanted to write something that was part memoir, part instruction manual; a series of observations and life lessons. Except he now worries he didn’t quite bring it off, he says. The book is too scattershot and inconclusive. He jokes that he ought to have called it Confusions instead.

Point Blank

It’s the dead of winter when I arrive at the Glebe, his secluded home in the Wicklow mountains. Boorman is bundled in a knitted jumper, his hair platinum as if from the frost. There is a daily allocation of pills on the table, a walker at his elbow and a stack of Oscar screeners (Hustlers, Booksmart, The Irishman) on the coffee table by his knee. When I ask how he is, he briskly lists all his ailments: hearing loss, failing eyesight, neuropathy, the works. “Old age is a series of giving things up. I can’t swim, I can’t run, I can’t drive a car or ride horses. I take a daily walk up the drive and back. Break the journey on a wooden bench.” He laughs shortly. “It usually takes me about an hour.”

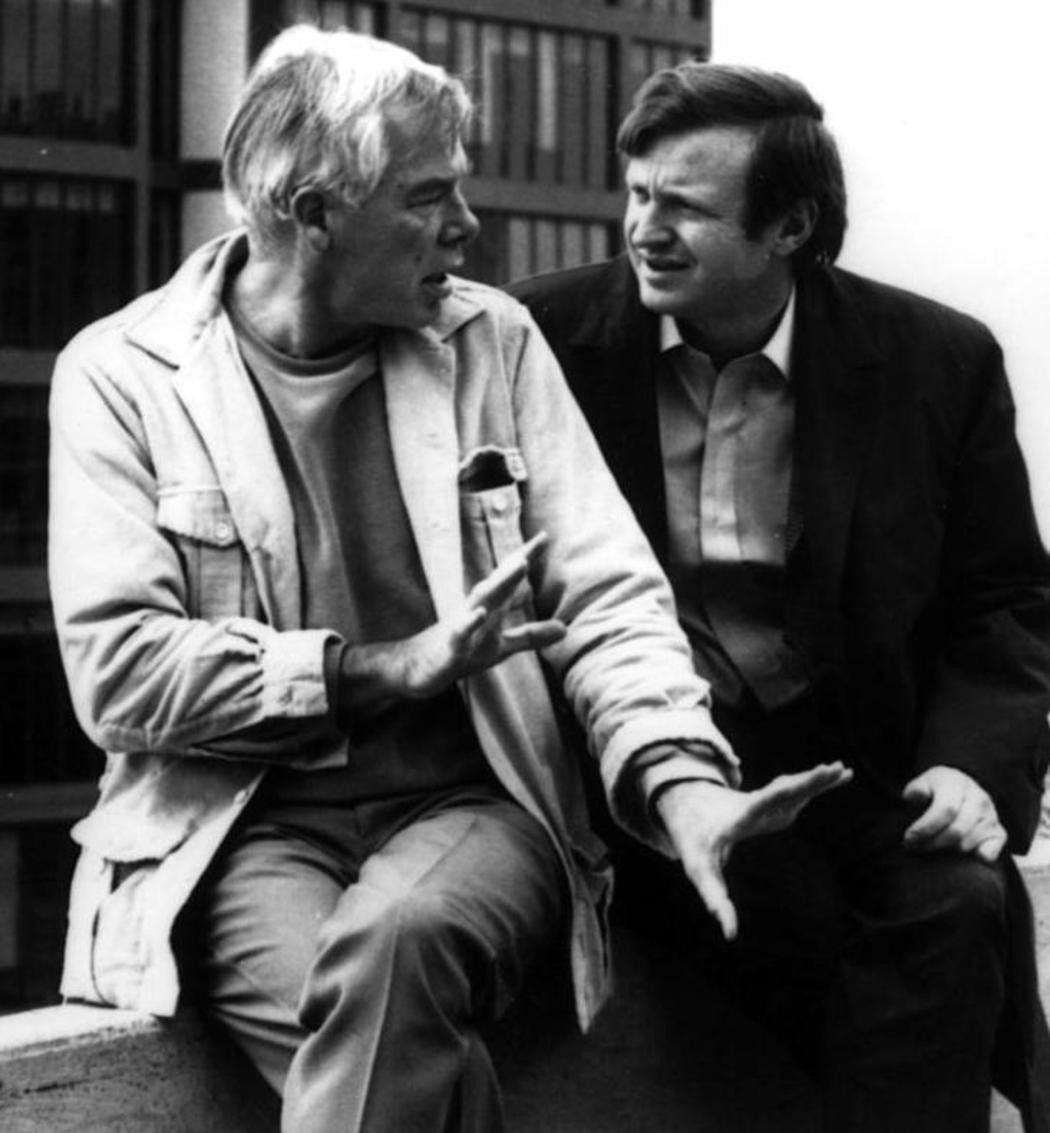

If Boorman risks pushing himself too hard, that’s surely because he’s a natural-born drill sergeant; his own harshest critic. In the case of Conclusions, I think his doubts are unfounded. The book’s a lovely miscellany, loose and limber, juggling film-making tips (“Don’t make the script too good”) with gossipy recollections of 60s and 70s Hollywood. Back then, Boorman could hardly turn a corner without running into the likes of Marlon Brando, Billy Wilder, Akira Kurosawa or Cary Grant. The existential Point Blank (1967) got him noticed; the mighty Deliverance (1972) made him a star. The way Boorman tells it, there was no master plan. He bounced from the bedsits of London to the BBC to a lucrative film-making career overseas.

Deliverance

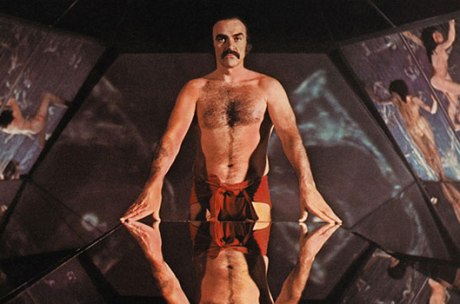

The Hollywood years were good while they lasted. But, by and large, he says he preferred independence: less money, more freedom. Boorman was always happier in the mainstream than Nicolas Roeg or Ken Russell, his closest contemporaries. But his work has a similar cockeyed abandon, a similar whiff of pagan mysticism. Films such as Zardoz, Excalibur or The Emerald Forest feel borderline malarial, on the brink of overheating. You watch them nervously, concerned for their safety.

He shrugs. “Well, I have a different relationship with different films. When I see Point Blank again I think: ‘How on earth did I get away with that?’ And Deliverance is very compelling. The craftsmanship is good. And as for Zardoz, I don’t know what the hell it is. But I think they’re all bold films, for better or worse.”

Then there are the ones that got away. The hits (such as Rocky and Alien) he turned down because the scripts left him cold. Or the passion projects he was forced to abandon. Boorman estimates that he spent more time on the films that didn’t get made than on those that did.

Zardoz

In the early 70s, for instance, he corresponded with JRR Tolkien about a screen adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, a full 30 years before Peter Jackson brought it safely home. Boorman wanted to shoot the whole saga as a single three-hour picture. “I saw it as this big dystopian story,” he says. “And in this house, upstairs, we papered the walls with each scene. We’d look at it, stare at it and try to get some sense out of it. And I had all sorts of solutions. I was going to cast nine- or 10-year-old boys as the hobbits. Put them in makeup; beards and things. And then dub them with adult voices.”

Jesus, I say. It would have been a disaster.

“Yeah well,” he chuckles. “It might have been.”

The director released his last feature film – the gentle, semiautobiographical Queen and Country – in 2015. Some days he thinks he would like to make another. Mostly he is glad to have put all that bother behind him. He has spent the bulk of his life at cinema’s beck and call, simultaneously loving it and hating it, like Ulysses lashed to the mast of his ship. It’s a blessed relief to be cut down at last.

The General

This reminds him of a story. In 1997, he made The General, a superb true-crime drama about the Dublin gangster Martin Cahill. On the eve of production, a doctor told him that he could drop dead at any second, and needed a heart bypass right away. “I’m shooting a film!” Boorman snapped back. “And that’s much more important than life or death.”

Happily for him, the diagnosis turned out to be wrong. It was a false negative; his heart was clear. Even so, what an idiot, right? “Looking back at it objectively, it was a ridiculous thing to say and do. Your life is at risk, and you go shooting a film? But that’s honestly how I saw it – as something more important than reality. I don’t any more.” He frowns. “I don’t think that I do.”

It’s cold in the room; Boorman reaches for a blanket. Probably the house has grown too big for his needs. The Glebe is a former rectory, built on the old monastic lands of Glendalough. His neighbour on one side is a 96-year-old hill farmer who still gets up for work every day. His neighbour on the other is Daniel Day-Lewis, recently retired. “Given up,” the director says. “The process made him exhausted. He felt all hollowed out and depressed. So I think in the end, he had just had enough.”

Hope and Glory - shamefully not mentioned here...

Boorman bought the Glebe in auction in 1969 and it went on to become the perfect family home, a base camp for adventure. Conclusions recounts boozy dinners and festive get-togethers. One night, Lee Marvin sat drunk at the head of the table; on another, Sean Connery spun tales of childhood poverty back in Scotland. Now Boorman has the entire place to himself. He is twice-divorced, and the kids have flown. He looks forward to visitors, but breathes a sigh of relief when they go.

“At my age, so many of my friends are dead that I have a feeling of being marooned,” he says. “My generation is nearly gone. So I just have to accept that’s the way things are. One thing after another disappears. You get more and more isolated. And, finally, you die.”

He suspects he has become something of a hermit. But that’s not so bad; he enjoys his own company. The only time he feels lonely is when he wakes in the night and needs to pee. He’ll creep half-asleep out of bed without turning on any lights to avoid waking his wife, and only twigs that the place is empty when he is picking his way blindly along the upstairs landing.

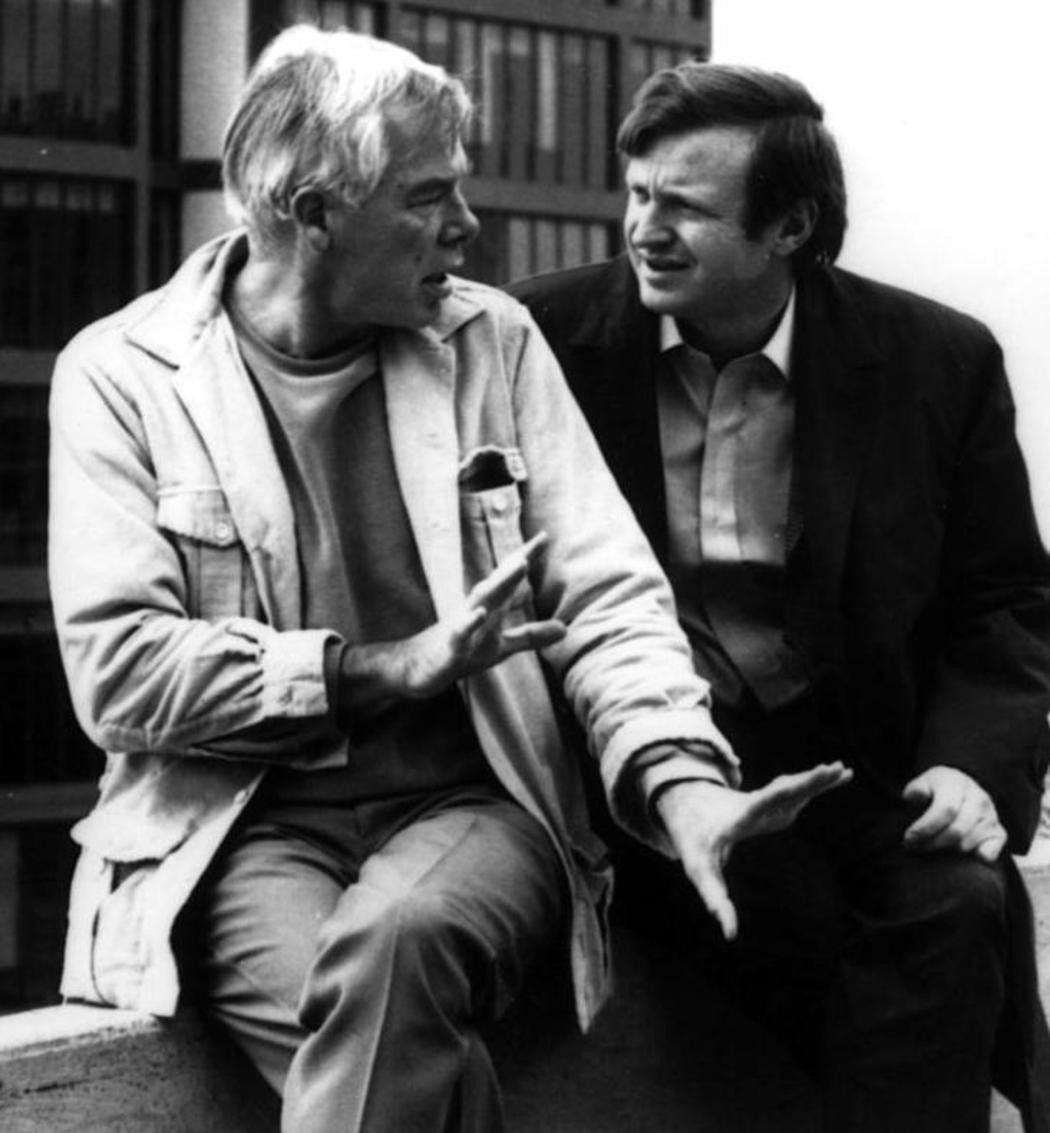

With Excalibur

We sit in the living room, variously gazing out at the trees or up at the bookshelves. I ask which possessions in the house are of particular value, and he points out the bronze cast of the hands of his eldest daughter, Telsche, who died of ovarian cancer more than 20 years ago. He also has Excalibur propped in a corner of the room – forged especially for the film by Wilkinson Sword. I pull it from the sheath; the blade is heavy and bright. Boorman’s humid account of King Arthur knocked me for six when I saw it as a kid in 1981. Brandishing the sword, I feel like the star of my own private mock-epic.

“Oh, and one other thing,” the director says at my back. “You think the holy grail is lost? Well, actually, no. I have it on my piano.”

Making films was always an escape for Boorman; a distraction from the inevitable. “When you’re shooting a film, you can convince yourself that death does not exist. I suppose that’s true of a lot of other activities. Sex or work or whatever it is. But it’s about being so busy and so focused that all thoughts of death just fall away.”

Making films was always an escape for Boorman; a distraction from the inevitable. “When you’re shooting a film, you can convince yourself that death does not exist. I suppose that’s true of a lot of other activities. Sex or work or whatever it is. But it’s about being so busy and so focused that all thoughts of death just fall away.”

Excalibur

Thinking about it now, he reckons he has always been much braver on set than off it. “Oh definitely,” he says. “I’ve done stuff in films that I wouldn’t have dared to do in normal circumstances. In my life, in my family, in my relationships, I’ve been cowardly. Whereas if I’d been presented with the same kind of problems on a film set, I feel that I would have been very brave and decisive.”

We prop the sword back in its corner and retreat to the kitchen for fishcakes and white wine. The director accepts that the sensible solution would be to move out of the house. His daughter, Daisy, has a small flat in London where she would like him to live. But so far he has been resisting. He says the very thought makes him claustrophobic. On top of all that, it would mean saying goodbye to his trees. He suspects that the trees still have something to tell him. He would like to learn how they manage to communicate with one another, or the process by which sap travels up a trunk.

Boorman has spent the large part of his life in a romantic entanglement with the movies. He seems to be ending it infatuated by trees. That’s quite the violent change of gears. I can’t imagine there’s any connection there. “Well, you see,” he says. “I think perhaps there is. Because when you’re making a film, you are trying to find the essential truth of it. You’ve got the script and the actors. But what’s underneath that, and where is it going? And all the while, the film is changing and growing around you. You’re trying to hold on to a vision, but at the same time you have to go with the flow. And that’s the way I look at trees. You plant them. Lots of them die. Some of them are eaten by other animals. And some of them survive, grow and become these great giants.”

The director nods at the window and the wintry garden outside. “I bought this house 50 years ago,” he says. “So I’ve seen the span of the trees on the land. A lot of the trees that I planted, I’ve now outlived. The rest of them will outlive me.”

No comments:

Post a Comment