The singer has written many beautiful songs – and was a muse for Joni Mitchell and Carole King. He reflects on his relationship with Mitchell and overcoming childhood trauma and heroin addiction

Jenny Stevens

The Guardian

Mon 17 Feb 2020

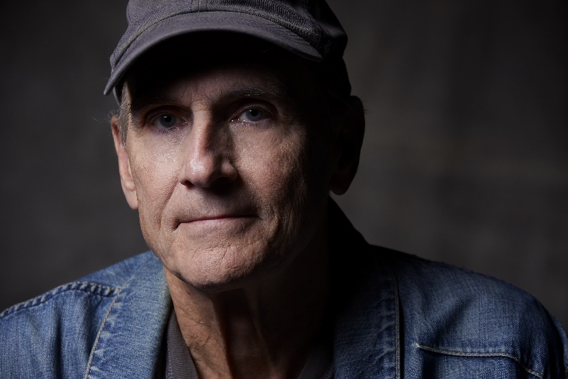

James Taylor looks out at the sprawling London skyline. “This is where it started,” he says. “The moment.” He made his first trip here in 1968, playing for Paul McCartney and George Harrison and becoming the first artist signed to the Beatles’ record label, Apple Records. This was before he moved to Laurel Canyon with the rest of the denim-draped California dreamers who defined the sound of the late 60s and far beyond. Before he met David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, Neil Young, Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Carole King and Joni Mitchell. Before he and Mitchell fell in love. Before he wrote his pivotal album Sweet Baby James during a stint in a psychiatric hospital. Before his marriage to Carly Simon, which opened up his personal life – including his long battle with heroin addiction – to public consciousness. Before he sold 100m records, performed for the Obamas and the Clintons, and then, decades later, appeared on stage with one of the world’s biggest pop stars, Taylor Swift, who is named after him.

It has been quite the trip, he admits.

Taylor is in a reflective mood when we meet, and says he is always like this. “I’m a very self-centred songwriter. I always have been. It’s the personal stuff I like, for better or for worse.” He is here to promote his 19th album, American Standard; a covers album of the old standards and Broadway show tunes he was raised on. He says there was a period when his generation wanted to distance themselves from this music, but he now recognises it as “the pinnacle of American popular song ... It was sheet music, anyone would sing it, so the songs had to stand on their own. It’s what informed me as a songwriter, and others of my generation; Lennon and McCartney, Randy Newman, Elton [John] and Bernie [Taupin], Paul Simon ...”

He has also released an audio memoir – Break Shot – which takes him back to his turbulent early years, finishing with that first London trip. He is anxious, he says, about how the memoir will be received. It covers his father’s alcoholism and his brother’s death from the disease, as well as his own drug addiction, all of which, he worries, could be sensationalised. But the memoir is mostly about the shattering effect that early childhood trauma, addiction and grief can have generations later. It’s a subtle exploration of the “ripples”, as Taylor puts it.

Born in Boston in 1948, Taylor was, according to his memoir, “brought up devoted to progressive politics, self-improvement and the arts”. His father, a doctor, moved the family to the south when he became the dean of the medical school of the University of North Carolina; his mother didn’t want to go, and fought against the politics she found there. She saw the north-eastern state of Massachusetts as a “lost Eden” and would spend her days doing sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, on protests, and hauling her five kids to Martha’s Vineyard every summer to “restore our Yankee credentials”. Not long after moving the family to North Carolina, Taylor’s father was assigned to the navy. He spent two years on an expedition to the south pole, where he held the keys to the liquor cabinet of 100 men. He went to the bottom of the world and returned with a serious drinking problem.

“There’s a mysterious energy to someone who lives with a tragedy like this,” Taylor says of his father. “It’s like when you take your report card home from school and you know that if you hand it to him before he’s had his first drink, you’re going to get one response and if you hand it to him after his first drink, you’ll get another.”

Was his dad abusive? “No,” he says firmly. “My father was a remarkable and powerful and beautiful guy who self-medicated with alcohol ... But he was by no means an abusive or stumble-bum or knee-walking or ditch-sleeping drunk.”

Still, an unpredictable parent is rarely a recipe for a stable adulthood. “Sure,” he says. “But complacent happiness is not a gift of the gods, either.”

Taylor began playing guitar in his teens, strumming along to his parents’ record collection: Harry Belafonte, Nina Simone, Judy Garland, Lead Belly. Fingerpicking became his vernacular as much as his lyrics. His first big hit, Fire and Rain, about the suicide of a friend, includes the themes that came to define his songwriting – the precarity of our emotional lives, happiness as something to be treasured and the natural world’s capacity for renewal. The line “I’ve seen lonely times when I could not find a friend,” prompted Carole King to write You’ve Got a Friend for him in response.

It was during high school that he and his family began to unravel. He was admitted to the McLean psychiatric hospital at 16 with what we would now probably call depression and anxiety, staying there for nine months. Two of his siblings followed him there. “When I jumped the tracks and went to McLean, it’s like they thought: ‘Yeah, that’s right, we need this help.’ It became an option.”

When Taylor left hospital, the fund set aside for his university tuition had been spent on his treatment and he decided to go to New York to pursue music. He formed a band, the Flying Machine, and developed a heroin habit. “To be able to take a juice that solves your internal stress ...” he trails off. “One of the signs that you have an addiction problem is how well it works for you at the very beginning. It’s the thing that makes you say: ‘Damn, I like my life now.’ That’s when you know you shouldn’t do it again.” His wasn’t the addiction of rock mythology, chaotic and glamourised. Taylor says mostly he used the drug to “get normal”. Taylor’s breakout second album, Sweet Baby James.

Mon 17 Feb 2020

James Taylor looks out at the sprawling London skyline. “This is where it started,” he says. “The moment.” He made his first trip here in 1968, playing for Paul McCartney and George Harrison and becoming the first artist signed to the Beatles’ record label, Apple Records. This was before he moved to Laurel Canyon with the rest of the denim-draped California dreamers who defined the sound of the late 60s and far beyond. Before he met David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, Neil Young, Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Carole King and Joni Mitchell. Before he and Mitchell fell in love. Before he wrote his pivotal album Sweet Baby James during a stint in a psychiatric hospital. Before his marriage to Carly Simon, which opened up his personal life – including his long battle with heroin addiction – to public consciousness. Before he sold 100m records, performed for the Obamas and the Clintons, and then, decades later, appeared on stage with one of the world’s biggest pop stars, Taylor Swift, who is named after him.

It has been quite the trip, he admits.

Taylor is in a reflective mood when we meet, and says he is always like this. “I’m a very self-centred songwriter. I always have been. It’s the personal stuff I like, for better or for worse.” He is here to promote his 19th album, American Standard; a covers album of the old standards and Broadway show tunes he was raised on. He says there was a period when his generation wanted to distance themselves from this music, but he now recognises it as “the pinnacle of American popular song ... It was sheet music, anyone would sing it, so the songs had to stand on their own. It’s what informed me as a songwriter, and others of my generation; Lennon and McCartney, Randy Newman, Elton [John] and Bernie [Taupin], Paul Simon ...”

He has also released an audio memoir – Break Shot – which takes him back to his turbulent early years, finishing with that first London trip. He is anxious, he says, about how the memoir will be received. It covers his father’s alcoholism and his brother’s death from the disease, as well as his own drug addiction, all of which, he worries, could be sensationalised. But the memoir is mostly about the shattering effect that early childhood trauma, addiction and grief can have generations later. It’s a subtle exploration of the “ripples”, as Taylor puts it.

Born in Boston in 1948, Taylor was, according to his memoir, “brought up devoted to progressive politics, self-improvement and the arts”. His father, a doctor, moved the family to the south when he became the dean of the medical school of the University of North Carolina; his mother didn’t want to go, and fought against the politics she found there. She saw the north-eastern state of Massachusetts as a “lost Eden” and would spend her days doing sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, on protests, and hauling her five kids to Martha’s Vineyard every summer to “restore our Yankee credentials”. Not long after moving the family to North Carolina, Taylor’s father was assigned to the navy. He spent two years on an expedition to the south pole, where he held the keys to the liquor cabinet of 100 men. He went to the bottom of the world and returned with a serious drinking problem.

“There’s a mysterious energy to someone who lives with a tragedy like this,” Taylor says of his father. “It’s like when you take your report card home from school and you know that if you hand it to him before he’s had his first drink, you’re going to get one response and if you hand it to him after his first drink, you’ll get another.”

Was his dad abusive? “No,” he says firmly. “My father was a remarkable and powerful and beautiful guy who self-medicated with alcohol ... But he was by no means an abusive or stumble-bum or knee-walking or ditch-sleeping drunk.”

Still, an unpredictable parent is rarely a recipe for a stable adulthood. “Sure,” he says. “But complacent happiness is not a gift of the gods, either.”

Taylor began playing guitar in his teens, strumming along to his parents’ record collection: Harry Belafonte, Nina Simone, Judy Garland, Lead Belly. Fingerpicking became his vernacular as much as his lyrics. His first big hit, Fire and Rain, about the suicide of a friend, includes the themes that came to define his songwriting – the precarity of our emotional lives, happiness as something to be treasured and the natural world’s capacity for renewal. The line “I’ve seen lonely times when I could not find a friend,” prompted Carole King to write You’ve Got a Friend for him in response.

It was during high school that he and his family began to unravel. He was admitted to the McLean psychiatric hospital at 16 with what we would now probably call depression and anxiety, staying there for nine months. Two of his siblings followed him there. “When I jumped the tracks and went to McLean, it’s like they thought: ‘Yeah, that’s right, we need this help.’ It became an option.”

When Taylor left hospital, the fund set aside for his university tuition had been spent on his treatment and he decided to go to New York to pursue music. He formed a band, the Flying Machine, and developed a heroin habit. “To be able to take a juice that solves your internal stress ...” he trails off. “One of the signs that you have an addiction problem is how well it works for you at the very beginning. It’s the thing that makes you say: ‘Damn, I like my life now.’ That’s when you know you shouldn’t do it again.” His wasn’t the addiction of rock mythology, chaotic and glamourised. Taylor says mostly he used the drug to “get normal”. Taylor’s breakout second album, Sweet Baby James.

One day, his father called him in New York. “He said: ‘James, you don’t sound too good.’ I wasn’t.” Taylor was strung out, broke and still very unwell. His dad drove through the night, arriving at his West Side apartment the next day. “It’s a cynical thing,” he says. “But, you know, a mother really has to be there. But a father? Well, you can construct a father out of a few good episodes.” It was on that long drive home that his father warned him opiates were like kryptonite to the Taylors. “As a kid, his uncle said to him: ‘If you’re a Taylor and you touch an opiate, you’re finished. You can just kiss your entire life goodbye.’” His father’s family had owned a sanatorium, the Broadoaks asylum in Morganton, North Carolina. “After the civil war, there was a huge opiate problem. A lot of the business in the sanatorium was treating addiction – a lot of mental health problems were secretly addiction problems,” he says.

Taylor boarded a flight to London shortly after New Year’s Day 1968. His friend had given him the number of Peter Asher, the brother of McCartney’s then girlfriend Jane Asher; he had just been hired as a talent scout for the Beatles’ new label. Asher liked Taylor’s demo and arranged an audition with McCartney and Harrison. “I was very nervous. But I was also, you know, on fire,” he laughs. “In my sort of mellow, sensitive way.” He played his song Something In the Way She Moves (a line Harrison pinched for the opening line of his song Something) and they signed him then and there to make his eponymous first album. At the time, the Beatles were making the White Album. “We intersected in the studio a lot,” says Taylor. “They were leaving as I was coming in. I often came in early and would sit in the control room and listen to them recording – and hear playbacks of what they had just cut.” Did you hang out together? “Yeah,” he says. I ask if the band was unravelling by that point. “Well, it was a slow unraveling, but it was also an extremely creative unravelling.”

Heroin and other opiates were very available and very cheap in London at the time. “I picked up pretty soon after I got here,” he says. “I started by …” he pauses. “I shouldn’t go into this kind of stuff. It’s not an AA meeting.” Then he continues. “But you used to be able to buy something called Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne, which was an old-fashioned medication. Essentially, it was a tincture of opium, so you’d drink a couple of bottles and you could take the edge off.” Was it hard to kick the habit, given the circles he was moving in? “Well, I was a bad influence to be around the Beatles at that time, too.” Why? “Because I gave John opiates.” Did you introduce him to them? “I don’t know,” he says. Lennon, by many accounts, picked up a heroin habit in 1968 that contributed to an unhealable rift in the band.

A year later, after being released from his Apple contract, Taylor went to a rehab facility and moved to Laurel Canyon in Los Angeles, a deep-green crease that runs through the Hollywood Hills – which was becoming a haven for the young, politically aware and creative. It was, he says, a rare instance where something heralded as a golden age really was one. A new generation of singer-songwriters came up through the Troubadour nightclub, their work focusing on the internal and domestic, and borrowing from the roots of American song: country, bluegrass, folk.

“It really was a perfect moment, that Laurel Canyon period,” Taylor says. “Carole lived up there, Joni and I lived in her house there for the better part of a year. The record companies were relatively benign and there were people in them who cared about the music and the artists – it hadn’t become a corporate monolith yet. There was a sense of there being a community: myself, Jackson Browne, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Crosby, Stills and Nash. David Geffen was in the mix a lot. Linda Ronstadt, Peter Asher, Harry Nilsson. You know, it was pretty much what they say. Things really worked well.”

While in rehab, he had written most of the songs for his second album, his breakout, Sweet Baby James. He enlisted King to play keyboard; he then played on her 1971 album Tapestry. His relationship with Mitchell lasted a year, much of it on the road: she was composing the songs for her classic album Blue – he, meanwhile, was writing his third album, Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon, including the gorgeous You Can Close Your Eyes, written for her. But behind the scenes, their relationship was struggling. As Taylor’s career took off, his addiction dragged him down again. Mitchell mourned their split on her album For the Roses in the song Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire, a devastating eyewitness account of a person “bashing in veins for peace”. I ask Taylor if he is able to listen to Mitchell’s music from that time. “Blue, oh yes,” he says. “And she sings so beautifully on my songs.” What about Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire? He goes quiet. “It’s not like listening to me,” he whispers.

What is it like? He hangs his head for some time, silent. “I’m not able to listen to it,” he says.

I ask if he’s still in touch with Mitchell and his face lights up for the first time. “We’ve continued to have a friendship and, well, I recently sort of re-engaged with Joni, and that’s been wonderful. She came to a show of mine recently, at the Hollywood Bowl, which was an unusual thing for her to do.” Mitchell has been recovering from a period of ill health after a brain aneurysm in 2015. “But she’s recovering, she’s coming back – which is an amazing thing to be able to do – and I wonder what she has to tell us about that.” When you say “coming back” does he mean she’s making music? “Yes, I think she’s coming back musically ... It’s amazing to see her come back to the surface.”

Taylor has four children: two with his first wife, Carly Simon, whom he married in 1972. And two with his third wife, Kim Smedvig, whom he married in 2001. Given the experience with his own dad, is he critical of himself as a father? “God, yes, definitely,” he says. “You know, my kids actually say to me: ‘You’re not your dad, you know? You can relax. You’re in no danger of repeating it again. For one thing, you’re sober, and for another thing you’re here and paying attention.’” He was 26 when he married Simon, who was four years his senior. He talks about their marriage very rarely. But she devoted most of her 2015 memoir to unpicking it. “I was very young,” he says. “And I would be an addict for another 10 years. I mean, you marry an addict, you just have no idea who this person is, and he doesn’t have any idea who he is either. It’s terrible.”

In 1983, Taylor got sober, attending AA. But it is an ongoing process, getting clean. He took methadone to address his heroin usage, and that became a “powerful addiction” in itself. “It really lives in your bones; I mean, it just takes for ever to get over it.” It helped to see addiction as a “physical disease”, too. “You’ve trained your body to accept a substance when you feel stress, but that help doesn’t last for ever. It has a negative progression. That’s the only reason people get better. And so you’re left with a feeling that when you encounter stress, you feel it physically, and it feels like withdrawing. It’s a nasty way to feel. And the only advice I give to people who are recovering from addiction is that physical exercise is the only antidote to feeling like you can’t stand being in your own skin.” Is that how it feels? “It’s terrible. It’s like you don’t want to be here,” he says, motioning to his body. “But in here is where you live.” For 15 years, Taylor exercised for hours every day: running and rowing. “It set me free,” he says.

He hopes this year to perform to help get out the vote ahead of the US presidential election. He met Donald Trump once, “in an airport. I just thought of him as a frivolous, minor player. It drives me crazy how unworthy he is of our attention and how much of it he has.” He is rooting for the Democratic candidates Deval Patrick and Elizabeth Warren – both from Massachusetts, where he now lives. “But at this point, I’d be happy to see pretty much anyone in – the bar is so low. Because the very worst person possible that you could think to be heading the thing is there. It’s like the Confederacy has won the civil war.”

As the interview ends, Taylor gets up and shakes my hand. I thank him for his honesty, and tell him his experiences – and the thoughtful way he talks about recovery – are doubtless helpful to other addicts. He leaves the room, comes back and shakes my hand again. Then he leans in and gives me a long, warm embrace, before heading off to be photographed, walking into the light again.

James Taylor’s new album American Standard (Fantasy Records) is released on 28 February

No comments:

Post a Comment