Squalor, glamour, wealth and cruelty: the Britain Van Gogh saw and loved

He painted prisoners, devoured Dickens and worshipped the London News … ahead of a major show, our writer reveals how Britain changed Van Gogh – and how he transformed its artCharlotte Higgins

The Guardian

Van Gogh is no longer merely a popular artist, he is a worldwide brand. In 2017, 2.26 million visitors passed through the doors of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, an astounding number for an institution devoted to the work of a single artist. In the shop, sunflowers, irises and almond blossoms emblazon every kind of item from spectacles to suitcases. His home village of Nuenen, on the outskirts of Eindhoven, where he spent important months training himself to be a painter – and where his father suddenly died, his girlfriend drank poison and the Catholic priest urged parishioners to stop sitting for him after one of his subjects became pregnant – is now a place of pilgrimage, with an visitors’ centre and coach-loads of tourists in the summer. The Noordbrabants Museum, in nearby ’s-Hertogenbosch, which holds a small but important collection of early works by the artist, even stocks in its shop a rubber in the shape of a severed ear (an “earaser”, if you please).

The painting that sparked Van Gogh’s love of London: The Victoria Embankment, London, 1875, by Giuseppe de Nittis.

The painting that sparked Van Gogh’s love of London: The Victoria Embankment, London, 1875, by Giuseppe de Nittis.

Because of all this, it is hard to separate Van Gogh the global phenomenon from Van Gogh the real young man, tentative, passionate, principled, religious, curious, difficult. His curse and his blessing was his literary ability – and his extraordinary letters, which fleshed out his biography and made him an object of cultish fascination (and subject of plays such as Vincent in Brixton, and of films such as Lust for Life and Loving Vincent). The letters, preserved and promoted by his sister-in-law Jo van Gogh-Bonger, after Theo’s death from syphilis, also contain the material to rescue him from the wilder claims of the many observers who have struggled to separate his work from his mental state.

At the 1910 exhibition, the Observer’s critic, PG Konody, wrote that at least some of his paintings were “merely the ravings of a maniac”. But letters show that whatever his mental illness consisted of, it was not a matter of a madman raging at a canvas, or a lunatic expressing distorted, hallucinogenic visions in paint. When he suffered his most intense periods of sickness, he did not – could not – paint. Perhaps our age, with its gradually increasing sensitivity to the nuances of mental ill-health, can be the one that finally removes the stigma.

Van Gogh lived in London before his momentous decision in 1879 to become an artist. (It is always extraordinary to recall that his active career was a mere decade in duration.) Working in Covent Garden at Goupil’s, as an art dealer specialising in reproductions, and lodging at Hackford Road in Lambeth, south of the river, he took long walks through the city streets, and often visited the National Gallery. A favourite painting in Trafalgar Square was Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis , which showed a distinctive flat Dutch landscape, with pollarded trees lining a lane that diminishes into the distance. It is the progenitor of many similar views by Van Gogh. According to Carol Jacobi, the curator of the Tate Britain show, it was also his reading of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress that made the “small figure on a long autumnal avenue” become a “visualisation of life as a journey”.

The Avenue at Middelharnis, 1689, by Meindert Hobbema

He described his own Avenue of Poplars in Autumn, which he made in 1884 in Nuenen, as a scene where “the sun makes glittering patches here and there on the fallen leaves on the ground, which are interspersed with the long shadows cast by the trunks”. Nine years earlier, when living in Britain, he had written out John Keats’s Ode to Autumn, in English, in a letter to Dutch friends.

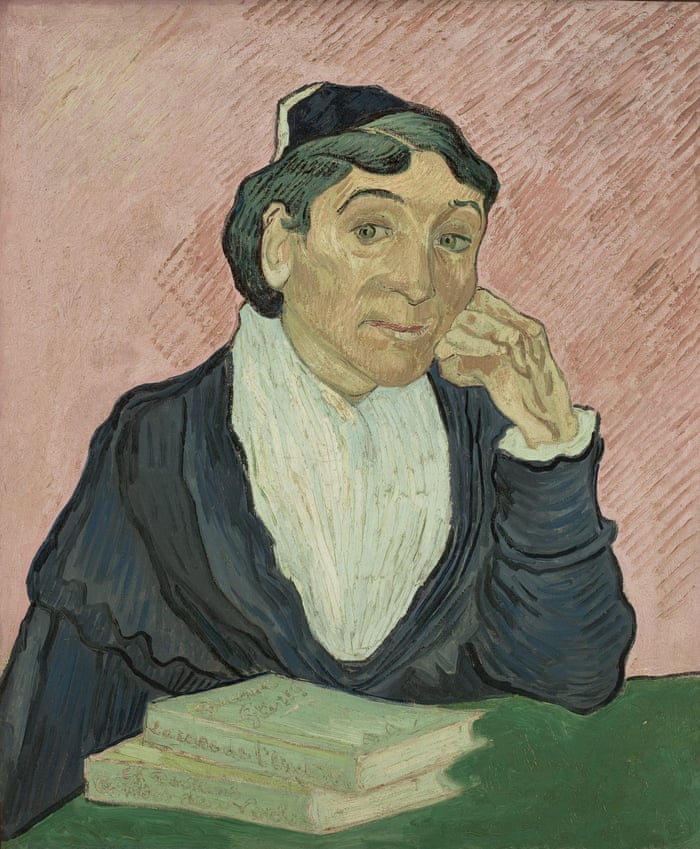

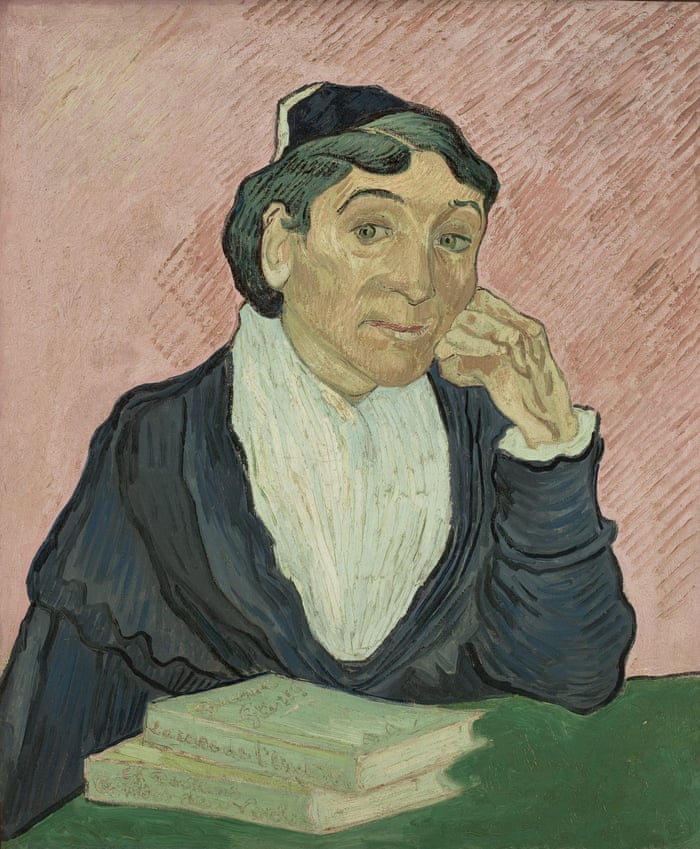

Van Gogh lived in London only three years after Dickens had died. Books such as Hard Times fed his empathy for the downtrodden. One of his late portraits of his friend Marie Ginoux, made in 1890 (and with which Tate Britain’s exhibition begins) shows her with copies of Dickens’s Christmas Stories and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the table in front of her. He also adored George Eliot. “Have you read anything good lately?” he wrote to Theo in 1878. “Be sure to get hold of the works of George Eliot somehow, you won’t be sorry if you do, Adam Bede, Silas Marner, Felix Holt, Romola (the life of Savonarola), Scenes of Clerical Life.”

Later he read Felix Holt in Dutch. “It is a book written with great verse, and various scenes are described as Frank Holl or someone similar might have drawn them. The way of thinking and the outlook are similar. There are not many writers as utterly sincere and good as Eliot.” When Van Gogh began drawing in Nuenen, he often made weavers his subjects. Even though industrialised textile-making was taking over in nearby towns such as Tilburg, there were still cottage weavers in the village, scraping a living from their slow, laborious work using a technology unchanged for centuries (in the Nuenen visitor centre, there is a beautiful 18th-century loom, just like the ones in Van Gogh’s drawings).

Marie Ginoux with copies of Dickens’s Christmas Stories and Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in one of Van Gogh’s L’Arlésienne paintings

Marie Ginoux with copies of Dickens’s Christmas Stories and Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in one of Van Gogh’s L’Arlésienne paintings

He was inspired by Stephen Blackpool, the weaver in Hard Times; and perhaps even more by Eliot’s weaver, Silas Marner. One drawing, from 1884, shows a weaver with a baby sitting nearby in a high chair, rather like one imagines Silas and little Eppie, the child he adopts in the book. Van Gogh saw himself as a weaver of sorts – like “someone who must control and interweave many threads … so absorbed in his work that he doesn’t think but acts, and feels how it can and must work out”.

The threads of Van Gogh’s influence wind their way into British art. Jim Ede, whose home became Kettle’s Yard gallery in Cambridge, and who worked at the Tate before its conservative policies wore him down, persuaded Bonger to part with the great Sunflowers canvas that is now displayed in the National Gallery. (It will move back to Tate Britain for the exhibition.) Those flowers launched a new wave of avant-garde still lifes on these shores, by artists from Frank Brangwyn to Samuel John Peploe to Matthew Smith to Winifred Nicholson. Oddly enough, though, it was the painting The Potato Eaters – a grim, dark-brown scene of hard-bitten village life that was his early masterpiece from the Nuenen years – that the public was especially drawn to.

In a country half-crushed by war, the Van Gogh they needed was the painter of hunger and toil and people of small means. It will be interesting to see what Van Gogh we find ourselves needing in post-Brexit London.

25 March 2019

Vincent van Gogh was the most European of artists. His brief, intense life, before he killed himself aged 37, saw him moving between his native Netherlands, Belgium, England and France. He spent two years in London from 1873 to 1875, employed by an art dealer; in 1876, for shorter periods, he worked as a teacher in Ramsgate and Isleworth. Later, when he was living in Paris, Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo about seeing a painting that depicted London from Victoria Embankment, by Giuseppe De Nittis. “When I saw this painting,” he wrote, “I felt how much I love London.” The city provided a deep immersion into the bewildering, heady life of a fully industrialised metropolis. This was Dickens’s London, with its squalor, its teeming masses, its glamour, its wealth, its cruelty – and, importantly for his formation, its art galleries.

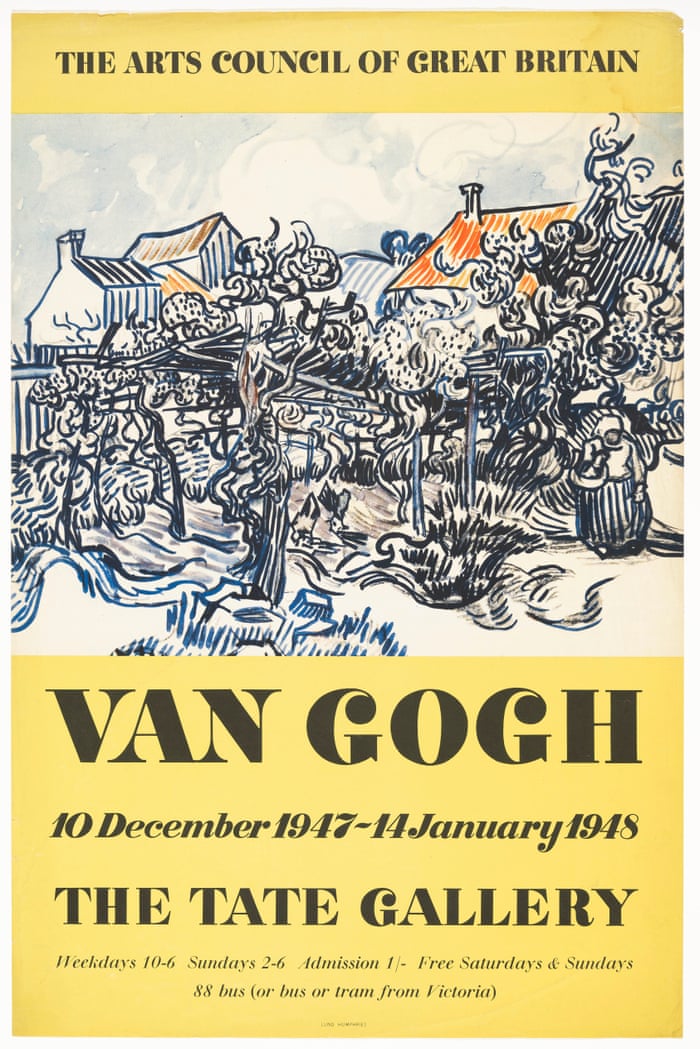

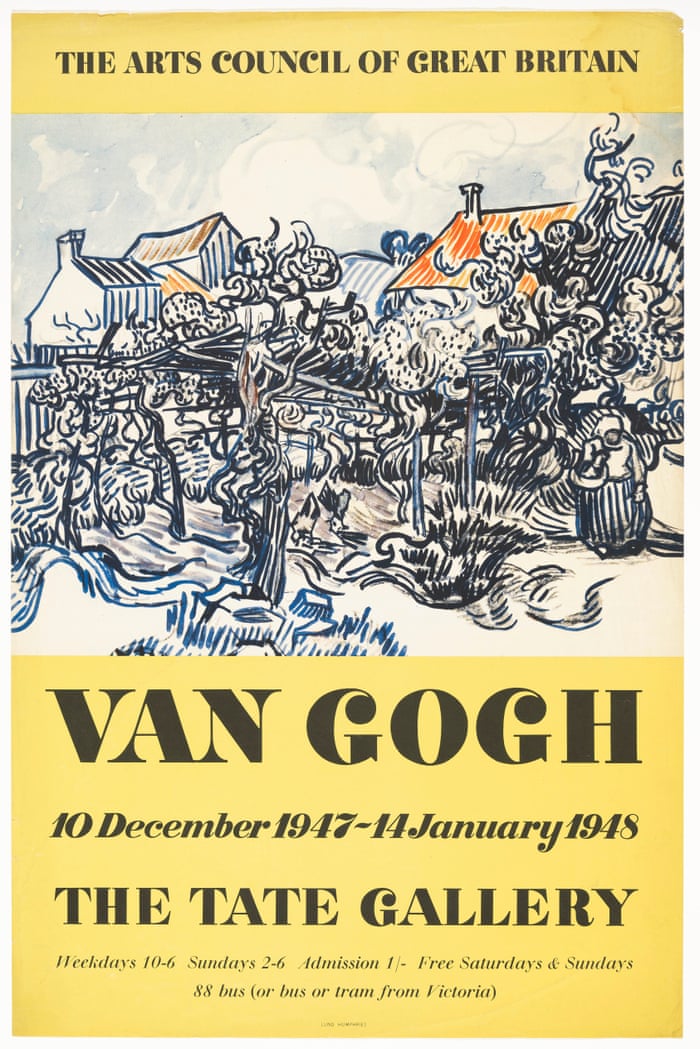

After his death, the love, at first fitfully, flowed in the opposite direction. When his work was shown at Roger Fry’s famous post-impressionist exhibition in 1910, it changed the course of British art. In 1947, bombed-out, austerity London was given a blast of the golds and scarlets and greens and azure blues of Provence, and Van Gogh’s paintings, by then sanctified into mass popularity, astounded the public once more.

Vincent van Gogh was the most European of artists. His brief, intense life, before he killed himself aged 37, saw him moving between his native Netherlands, Belgium, England and France. He spent two years in London from 1873 to 1875, employed by an art dealer; in 1876, for shorter periods, he worked as a teacher in Ramsgate and Isleworth. Later, when he was living in Paris, Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo about seeing a painting that depicted London from Victoria Embankment, by Giuseppe De Nittis. “When I saw this painting,” he wrote, “I felt how much I love London.” The city provided a deep immersion into the bewildering, heady life of a fully industrialised metropolis. This was Dickens’s London, with its squalor, its teeming masses, its glamour, its wealth, its cruelty – and, importantly for his formation, its art galleries.

After his death, the love, at first fitfully, flowed in the opposite direction. When his work was shown at Roger Fry’s famous post-impressionist exhibition in 1910, it changed the course of British art. In 1947, bombed-out, austerity London was given a blast of the golds and scarlets and greens and azure blues of Provence, and Van Gogh’s paintings, by then sanctified into mass popularity, astounded the public once more.

The Manchester Guardian’s critic, Eric Newton, wrote of that exhibition, held at what is now Tate Britain: “When he painted with reckless courage from a full heart … the results are astonishing. What is more, they will always be astonishing. That kind of genius cannot go out of fashion.” This month, Van Gogh will be returning to the building, as a major new exhibition examines his relationship with Britain – what he drew from it and what he bequeathed to it.

Van Gogh is no longer merely a popular artist, he is a worldwide brand. In 2017, 2.26 million visitors passed through the doors of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, an astounding number for an institution devoted to the work of a single artist. In the shop, sunflowers, irises and almond blossoms emblazon every kind of item from spectacles to suitcases. His home village of Nuenen, on the outskirts of Eindhoven, where he spent important months training himself to be a painter – and where his father suddenly died, his girlfriend drank poison and the Catholic priest urged parishioners to stop sitting for him after one of his subjects became pregnant – is now a place of pilgrimage, with an visitors’ centre and coach-loads of tourists in the summer. The Noordbrabants Museum, in nearby ’s-Hertogenbosch, which holds a small but important collection of early works by the artist, even stocks in its shop a rubber in the shape of a severed ear (an “earaser”, if you please).

Because of all this, it is hard to separate Van Gogh the global phenomenon from Van Gogh the real young man, tentative, passionate, principled, religious, curious, difficult. His curse and his blessing was his literary ability – and his extraordinary letters, which fleshed out his biography and made him an object of cultish fascination (and subject of plays such as Vincent in Brixton, and of films such as Lust for Life and Loving Vincent). The letters, preserved and promoted by his sister-in-law Jo van Gogh-Bonger, after Theo’s death from syphilis, also contain the material to rescue him from the wilder claims of the many observers who have struggled to separate his work from his mental state.

At the 1910 exhibition, the Observer’s critic, PG Konody, wrote that at least some of his paintings were “merely the ravings of a maniac”. But letters show that whatever his mental illness consisted of, it was not a matter of a madman raging at a canvas, or a lunatic expressing distorted, hallucinogenic visions in paint. When he suffered his most intense periods of sickness, he did not – could not – paint. Perhaps our age, with its gradually increasing sensitivity to the nuances of mental ill-health, can be the one that finally removes the stigma.

Van Gogh lived in London before his momentous decision in 1879 to become an artist. (It is always extraordinary to recall that his active career was a mere decade in duration.) Working in Covent Garden at Goupil’s, as an art dealer specialising in reproductions, and lodging at Hackford Road in Lambeth, south of the river, he took long walks through the city streets, and often visited the National Gallery. A favourite painting in Trafalgar Square was Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis , which showed a distinctive flat Dutch landscape, with pollarded trees lining a lane that diminishes into the distance. It is the progenitor of many similar views by Van Gogh. According to Carol Jacobi, the curator of the Tate Britain show, it was also his reading of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress that made the “small figure on a long autumnal avenue” become a “visualisation of life as a journey”.

The Avenue at Middelharnis, 1689, by Meindert Hobbema

He described his own Avenue of Poplars in Autumn, which he made in 1884 in Nuenen, as a scene where “the sun makes glittering patches here and there on the fallen leaves on the ground, which are interspersed with the long shadows cast by the trunks”. Nine years earlier, when living in Britain, he had written out John Keats’s Ode to Autumn, in English, in a letter to Dutch friends.

Van Gogh was deeply immersed in English (and French) literature. He read easily and quickly in the original languages. Dickens was a solace. When Van Gogh went into an asylum in Provence, late in his life, he bought copies of the novelist’s work in French translation. His famous paintings of empty chairs – his own, simple and rush-seated, and Gauguin’s, a more elegant piece of furniture in polished wood – echoed the touching drawing by Luke Fildes of the novelist’s empty chair made soon after his death. He loved Fildes’s socially aware images of the urban poor, and Gustave Doré’s print series of London scenes. Later on, he copied Doré’s print of prisoners exercising in Newgate, making a solemn, claustrophobic painting of it. He bought Fildes’s print Homeless and Hungry, which had appeared in weekly newspaper the Graphic in 1869.

“I used to go every day to the display case of the printer of the Graphic and London News … the impressions I gained there on the spot were so strong that the drawings have remained clear and bright in my mind,” he remembered later. Eventually, he collected around 2,000 such prints. When he started drawing seriously, he toyed with the idea that he could make a living selling work to such publications. “He was developing his singular, forceful line from the lines used in these etchings,” says Jacobi.

Vincent Van Gogh’s former home in south London“I used to go every day to the display case of the printer of the Graphic and London News … the impressions I gained there on the spot were so strong that the drawings have remained clear and bright in my mind,” he remembered later. Eventually, he collected around 2,000 such prints. When he started drawing seriously, he toyed with the idea that he could make a living selling work to such publications. “He was developing his singular, forceful line from the lines used in these etchings,” says Jacobi.

Van Gogh lived in London only three years after Dickens had died. Books such as Hard Times fed his empathy for the downtrodden. One of his late portraits of his friend Marie Ginoux, made in 1890 (and with which Tate Britain’s exhibition begins) shows her with copies of Dickens’s Christmas Stories and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the table in front of her. He also adored George Eliot. “Have you read anything good lately?” he wrote to Theo in 1878. “Be sure to get hold of the works of George Eliot somehow, you won’t be sorry if you do, Adam Bede, Silas Marner, Felix Holt, Romola (the life of Savonarola), Scenes of Clerical Life.”

Later he read Felix Holt in Dutch. “It is a book written with great verse, and various scenes are described as Frank Holl or someone similar might have drawn them. The way of thinking and the outlook are similar. There are not many writers as utterly sincere and good as Eliot.” When Van Gogh began drawing in Nuenen, he often made weavers his subjects. Even though industrialised textile-making was taking over in nearby towns such as Tilburg, there were still cottage weavers in the village, scraping a living from their slow, laborious work using a technology unchanged for centuries (in the Nuenen visitor centre, there is a beautiful 18th-century loom, just like the ones in Van Gogh’s drawings).

He was inspired by Stephen Blackpool, the weaver in Hard Times; and perhaps even more by Eliot’s weaver, Silas Marner. One drawing, from 1884, shows a weaver with a baby sitting nearby in a high chair, rather like one imagines Silas and little Eppie, the child he adopts in the book. Van Gogh saw himself as a weaver of sorts – like “someone who must control and interweave many threads … so absorbed in his work that he doesn’t think but acts, and feels how it can and must work out”.

The threads of Van Gogh’s influence wind their way into British art. Jim Ede, whose home became Kettle’s Yard gallery in Cambridge, and who worked at the Tate before its conservative policies wore him down, persuaded Bonger to part with the great Sunflowers canvas that is now displayed in the National Gallery. (It will move back to Tate Britain for the exhibition.) Those flowers launched a new wave of avant-garde still lifes on these shores, by artists from Frank Brangwyn to Samuel John Peploe to Matthew Smith to Winifred Nicholson. Oddly enough, though, it was the painting The Potato Eaters – a grim, dark-brown scene of hard-bitten village life that was his early masterpiece from the Nuenen years – that the public was especially drawn to.

In a country half-crushed by war, the Van Gogh they needed was the painter of hunger and toil and people of small means. It will be interesting to see what Van Gogh we find ourselves needing in post-Brexit London.

Van Gogh and Britain opens at Tate Britain, London, on 27 March.