Don McCullin review – witness for the persecuted

Tate Britain, London

This retrospective of the veteran photographer’s images of war, poverty and atrocity shines light on the unconscionable. It’s almost overwhelming

Adrian Searle

A Nikon camera body with bullet hole at Don McCullin, Tate Britain. Photograph: Daniel Leal-Olivas

A Nikon camera body with bullet hole at Don McCullin, Tate Britain. Photograph: Daniel Leal-Olivas

Tate Britain, London

This retrospective of the veteran photographer’s images of war, poverty and atrocity shines light on the unconscionable. It’s almost overwhelming

Adrian Searle

The Guardian

Mon 4 Feb 2019

Here is the camera that took a bullet instead of its owner. The military helmet and the light meter, passports and compass, all in a vitrine. Here is the American soldier, traumatised, staring back. Here are the villagers, displaced. Here are the living and here are the dead. Here are things I prefer not to describe.

Mon 4 Feb 2019

Here is the camera that took a bullet instead of its owner. The military helmet and the light meter, passports and compass, all in a vitrine. Here is the American soldier, traumatised, staring back. Here are the villagers, displaced. Here are the living and here are the dead. Here are things I prefer not to describe.

Cyprus, 1964

There are too many photographs in Don McCullin’s retrospective at Tate Britain. Room after room, on grey wall after grey wall, they keep on coming. These framed, mostly black and white images are a journey through the world and through the photographer’s life. Now 83, McCullin is a man who has seen too much and borne witness to too much. The too many and the too much are part of the point of this engrossing and demanding exhibition.

US marines, the Citadel, Hue, Vietnam, 1968

“Yo lo vi” – I saw it – wrote Goya, beside an image of people fleeing before advancing French troops, in one of the prints in his Disasters of War suite of etchings, made around 200 years ago. “And this as well,” he wrote, beside the subsequent image. Goya’s declarations might not always tell the literal truth of what he saw with his own eyes, but no such doubts accompany McCullin’s photographs.

There are too many photographs in Don McCullin’s retrospective at Tate Britain. Room after room, on grey wall after grey wall, they keep on coming. These framed, mostly black and white images are a journey through the world and through the photographer’s life. Now 83, McCullin is a man who has seen too much and borne witness to too much. The too many and the too much are part of the point of this engrossing and demanding exhibition.

US marines, the Citadel, Hue, Vietnam, 1968

“Yo lo vi” – I saw it – wrote Goya, beside an image of people fleeing before advancing French troops, in one of the prints in his Disasters of War suite of etchings, made around 200 years ago. “And this as well,” he wrote, beside the subsequent image. Goya’s declarations might not always tell the literal truth of what he saw with his own eyes, but no such doubts accompany McCullin’s photographs.

He was there, as the Berlin Wall went up, on the streets of Limassol during the Cyprus civil war, in the Bogside and in Stanleyville, Biafra and Vietnam. He was there with the lone gunman, crouching alert on the floor of the wrecked lobby of the Holiday Inn in Beirut. He was there with the corpse of the Congolese man, his brains shot out beside his bicycle.

People of the Karo tribe, 2004

He was also there when the woman, the very picture of a middle-class housewife, smiled back at his camera, as she was bundled away by the police at a Ban the Bomb protest at Aldermaston in the early 1960s. He also saw the homeless men asleep while standing, hands in pockets, heads lowered like horses, in Whitechapel in 1970. Disaster is so often close to home, in squalid rooms in Bradford, on East End doorsteps, in Toxteth and in Wigan.

A Palestinian mother in her destroyed house, Sabra Camp, 1982

There are so many great and terrible images here. I snatch at fragments – the kid in the Finsbury park youth club, the gawping blokes with their beers in the stripper pub, the big northern woman queuing with a shiny new shovel in her hand, like the latest accessory. Small consolations and momentary pleasures, along with death and starvation, misery and fear, remind us of a different everyday. Fishermen kick a football about on a Scarborough beach, the sky about to open on a moment of sun. The metal mirror of a Somerset dew pond, round as a plate. A knobbly knees contest in Southend-on-Sea. Then we are back, staring at collapsed staircases, like exposed entrails, spilling from a bombed apartment block in Homs, Syria, and with a man dying of Aids in Zimbabwe.

Near Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin, 1962

In these unrelenting scenes of trespass and tragedy we are left facing our own voyeurism, an increasing inability to process the mounting horrors. McCullin revisits his own work over and over again, as he prints and reprints his images in his darkroom, repeatedly trying to tease the best from his negatives. His returns to these images cannot be entirely healthy. Unless, that is, they inoculate him against their unconscionable power, both as images and as memories. The words “negatives” and “processing” have rarely felt so freighted.

Suspected Lumumbist freedom fighters being tormented before execution, Stanleyville, 1964

Many of McCullin’s photographs demand a long, strong look. Others we might want to swerve away from almost at the moment of recognition, only needing to see them once. They are already fixed in the developing fluid of the subconscious. Many of us of a certain age will have first encountered McCullin’s photographs by chance through the 1960s and 70s, in the Observer, in the Sunday Times Magazine. Many have been stirring around in my head for most of my life, irreducible and unforgettable.

Catholic youths attacking British soldiers in the Bogside of Londonderry, 1971

McCullin’s images brought the Vietnam war, starvation in Biafra, civil wars, post-colonial and nearer-to-home sectarian conflicts in Derry and Belfast, into our houses and into our heads in a way that television coverage never could.

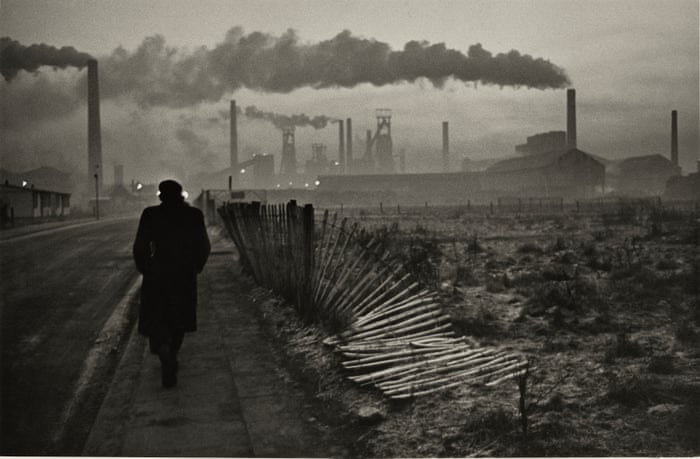

Early shift, West Hartlepool Steelworks, County Durham, 1963

Sometimes McCullin had to walk away. Sometimes I had to walk away from certain images, too. After a few rooms, I had to take a break from the grieving and the corpses, the starving and the terrified. Our hunger for images may be insatiable, but it becomes hard to concentrate and to give each image, taken at who knows what cost, its due.

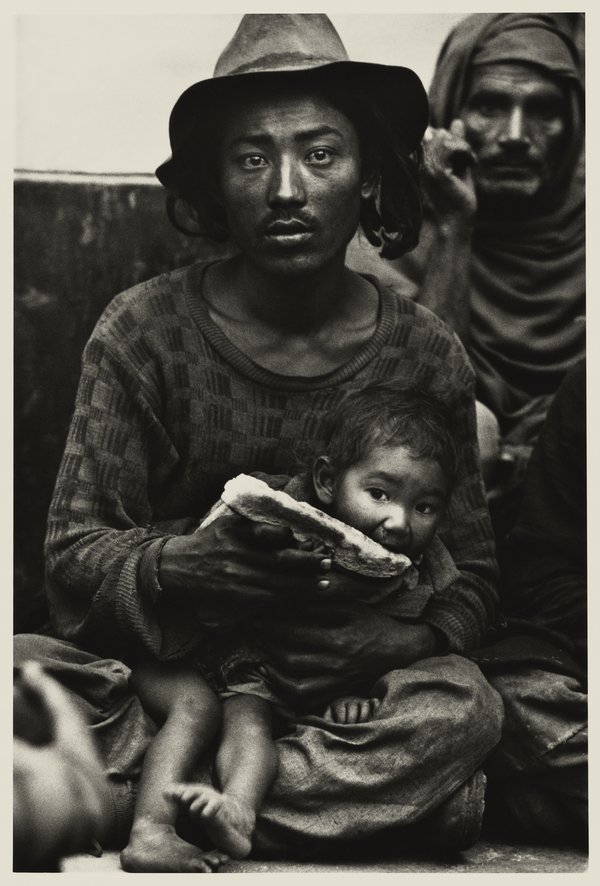

Strange Travellers: a destitute Tibetan family in the booking hall of railways station at dawn, Delhi, 1965

There is a visceral quality to McCullin’s photographs, in their analogue tonalities, the depth of their blacks and greys, the clarities and dimming of their whites, their strong and weak light, their focus, their attendance on the unconscionable. His insistence on black and white seems to lend his photographs an extra veracity, a sullen, stark truthfulness, stripped of any glamour. McCullin did more than record, even though the situations in which he frequently found himself necessitated instantaneous responses, before the mind with its mortal fear and terror, disgust, moral outrage and doubt, empathy, self-justification, self hate, all the qualms, had a chance to kick in.

Photography, he has said, chose him. The exhilaration of danger and the sound of gunfire found him, as much as he sought it out over his long career. Conflict was always round the corner for McCullin, even growing up in low-ceilinged rooms and poverty in Finsbury Park. Down the road, a man shepherds a flock to an abattoir through a grim north London dawn.

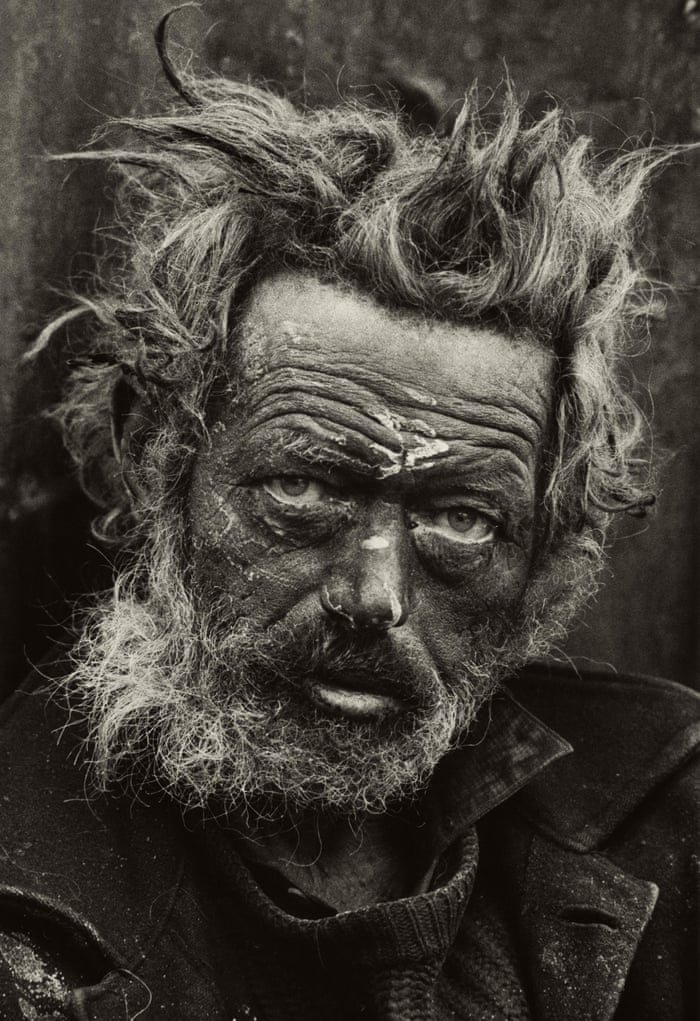

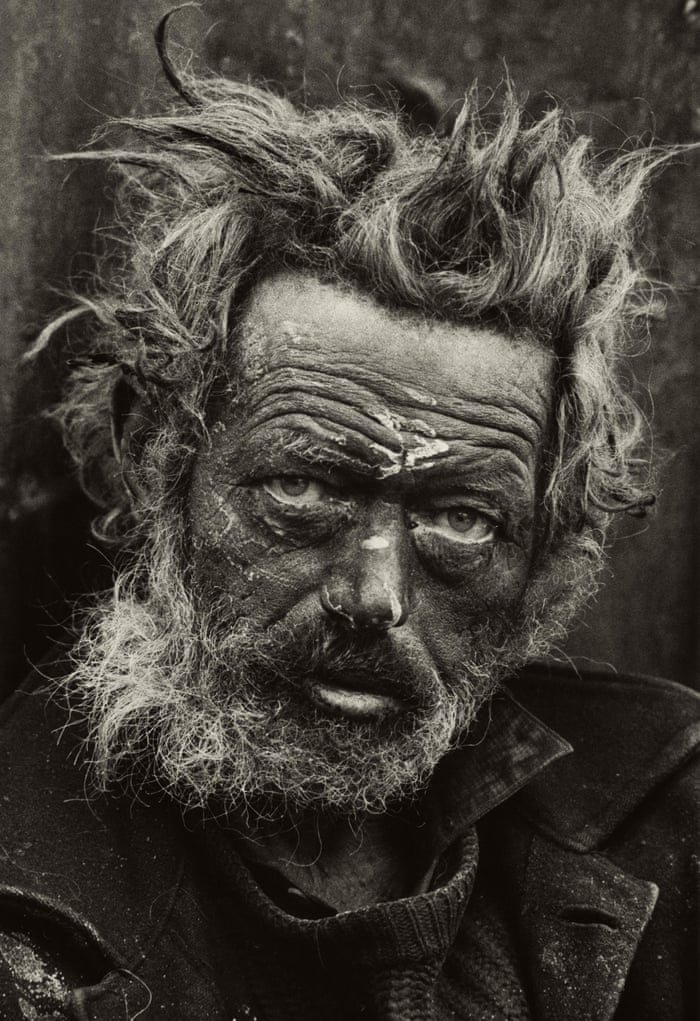

Homeless Irishman, Spitalfields, London, 1970

Where the homeless stood around reeking fires of rubbish in Spitalfields market half a century ago, they sleep in corporate doorways now. The wars continue. There is no end to the poverty, nor to the atrocities. Looking away is not an option.

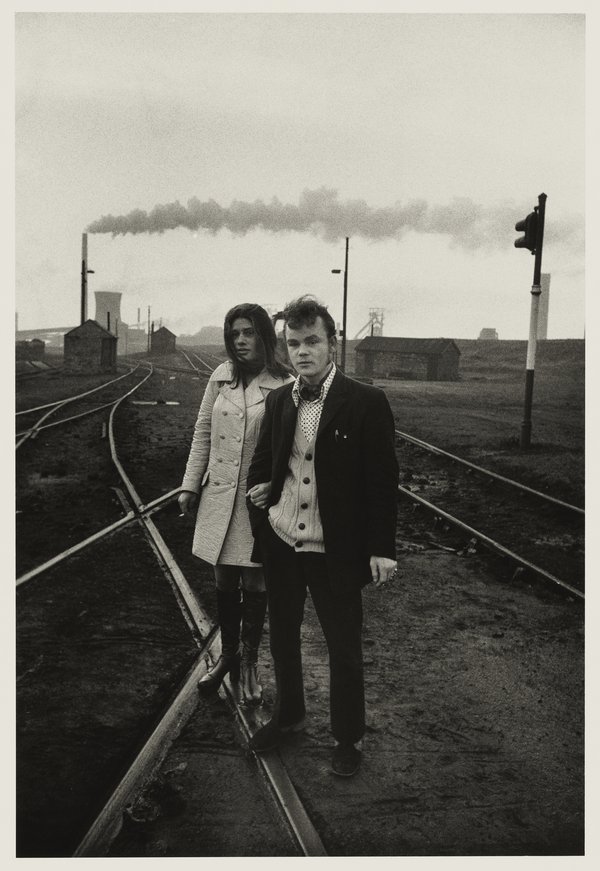

Consett, County Durham, 1974

At Tate Britain, London, from 5 February to 6 May.

No comments:

Post a Comment