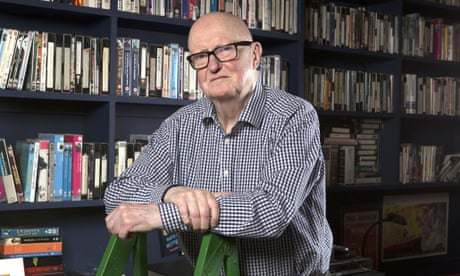

Philip French, much-loved Observer film critic, dies at the age of 82

The award-winning reviewer, who wrote for The Observer for 52 years, has died, two years after retiring

Catherine Shoard

Tuesday 27 October 2015

Philip French, who was the Observer’s film critic for 35 years, has died. Following several years of ill health, French suffered a heart attack on Tuesday morning at the age of 82.

He is survived by his wife, Kersti, sons Sean, Patrick and Karl, and 10 grandchildren.

French became one of the country’s best-loved film writers after becoming the chief critic at the Observer in 1978 following a distinguished career at the BBC.

He was named the British Press Awards Critic of the Year in 2009 and given an OBE in the 2013 New Year Honours for services to film. Later that year, when he turned 80, French retired from his position at the Observer, but continued to write every week for the paper.

Observer editor John Mulholland said he was “a giant figure” in the paper’s history and “part of its soul for the past 50 years”.

“He was a brilliant critic whose erudition and judgement were respected by generations of cinema lovers and film-makers alike. He was also a joy to work with, unfailingly warm and generous to colleagues and to the thousands of readers he encountered. He is revered as one of the most astute critics of his generation, whose love of film shone through his lucid and engaging writing. He will be missed sorely, but he will be remembered with affection and respect by his legion of admirers.”

Speaking to the Guardian this morning, his son Sean remembered a man who took seriously his role as a cultural commentator, “pointing people to the excitement and pleasure of the cinema and guiding them to what he thought was important”.

“He was extremely moral about his work. He didn’t see it in any frivolous way. One of the most shocking things to him was the idea of leaving a screening before the credits had rolled. It was one of the worst signs of decadence.”

Even in his final years, French continued his passion for cinema, watching even more movies than when a full-time reviewer.

“He was never going to be one to dig the garden,” said Karl. “And so while being immobile would be catastrophic for some people, keeping his mind alert was what mattered.”

“I think he’d be very happy to be remembered as a film critic,” said Patrick. “He thought it was useful. Right up to day he died, he did what he loved.”

French was born in Liverpool in 1933. He developed an early love of movies – westerns and musicals in particular – as an antidote to bleak, post-war Britain. Even when unfashionable, he championed Hollywood product right through his career.

Employed as a radio producer by the BBC from 1959, French spent a lot of time in America and was highly-knowledgable about US politics as well as culture.

He began his writing career as a reporter for the Bristol Evening Post in 1967 before working as a theatre critic at the New Statesman. French went full-time at the Observer in 1978, a paper for which he started writing in 1963.

Fellow journalists have paid tribute to the writer, with Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw calling him “a great cinephile and a lovely man” and the Times’s Kate Muir a “wonderful, erudite film critic”. Others praised his “immense warmth, wit and good humour” and well as his generosity and eagerness to share his knowledge.

Mark Kermode, who took over as chief Observer film critic in 2013, said:

Philip’s noble, erudite writing elevated film criticism to the level of art. His judgement was acute but always generous, his prose beautiful, his knowledge breathtaking. He was an inspiration to an entire generation of film critics, and was always wonderfully supportive of his colleagues; encouraging, wise and kind. He is irreplaceable.

Sean said that his father was much like the man readers encountered on the page: erudite, enthusiastic and playful.

“If readers felt they knew him it’s because he put his personality into the writing. He was a very funny man, with a slightly grim comic view of the world and this obsessive thing about puns.”

One of the lines of which French remained most proud, he recalled, was the opening line of an essay on British cinema and the Post Office: “I don’t know much about philately, but I know what I lick.”

http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/oct/27/philip-french-much-loved-observer-film-critic-dies-at-the-age-of-82

'I figured I'd retire gradually, just ride off into the sunset ...'

Clint Eastwood is one of the legends of American cinema, and still prodigious at 76 having just completed two acclaimed films. Tonight he is in line for yet another Oscar - some journey for the cowboy who first appeared in Rawhide in 1959. Last week in Paris the Observer's own legend, film critic Philip French, met the American director to discuss a shared love of westerns, the Golden Age of Hollywood and a lifetime in films.

Philip French

Sunday 25 February 2007

Clint Eastwood is the last major figure in international cinema to have served, and benefited from, an extended apprenticeship. Born in May 1930, the son of a blue-collar oil worker who moved around California during the Depression, he had numerous jobs, an interrupted education and an obligatory stretch in the army before becoming a minor contract performer at Universal. Luck intervened when he was signed up to play Rowdy Yates in the long-running TV western series, Rawhide. Luck intervened again when Italian director Sergio Leone, searching for a cheap Hollywood star, brought Eastwood to Italy in 1964 for the first major spaghetti western, A Fistful of Dollars. Eastwood continued to work on Rawhide while two profitable sequels were made, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. This trilogy of violent, cynical movies made him world famous.

Hollywood rushed in and Eastwood became a star. Most important, he established a long-running partnership with maverick director Don Siegel. Their major success was the controversial cop movie Dirty Harry (1971), and Eastwood made his directorial debut the same year in Play Misty for Me, in which Siegel had a cameo role.

After that, Eastwood took his career in his own hands, acting, directing and producing. His first, fully achieved masterwork was The Outlaw Josey Wales, made in the bicentennial year of 1976, and he went on to win Oscars for best film and director on two films, Unforgiven and Million Dollar Baby.

At 76, he has reached his peak with two movies about the Second World War battle for Iwo Jima. Flags of Our Fathers looked at three of the American invaders who helped raise Old Glory over Mount Suribachi and, as a result of an iconic photograph, were whisked home to figure in war-bond rallies. Letters From Iwo Jima, made in Japanese, looks at the invasion from the Japanese point of view. The latter has been nominated for best picture, director and screenplay at tonight's Oscars.

I first met Clint Eastwood 30 years ago at an extraordinary conference of historians, sociologists and film-makers gathered at Sun Valley, Idaho, in the bicentennial week of 1976 to address ourselves to the theme, 'Western Movies: Myths and Images', organised by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Levi-Strauss Corporation, the so-called Cowboys' Tailor. I was there to give a lecture on 'Politics and the Western'. Eastwood was the guest of honour, presenting the world premiere of The Outlaw Josey Wales. I'd rarely encountered a film-maker so open and relaxed.

When we met in Paris last week, he was the subject of the latest editions of France's movie journals, Cahiers du cinema and Positif, and visible everywhere. Looking fit, upright, relaxed, cheerful, he flashed that welcoming grin that is the other side of the taut, menacing face of the Man With No Name in the Leone westerns and the ironically quizzical Inspector Harry Callaghan.

Our conversation took place at the Ritz, the day before he received the Legion d'honneur from President Jacques Chirac.

PHILIP FRENCH What drives you on? You've been involved as director, producer, actor in more than 60 movies in the past 40-50 years and yet a contemporary like Warren Beatty makes one film every five or six years and Terrence Malick makes one every 15 years. Is it the fun of making movies? Is it the Protestant work ethic?

CLINT EASTWOOD It's just a bit of work ethic. It becomes part of my life and, if I have any virtues, which are probably not many, I get fairly decisive about things. When I find something I like, I usually know it pretty soon and I don't have to talk myself into much. I probably shoot from the hip a little more than Warren Beatty or other people. They probably ponder things more and I say: I like this, let's go. I don't sit and dwell on it too much. I dwell on it as I make it.

I guess everybody's a little different. Warren got up at the Golden Globes and he says: 'How do you it - having to do two pictures in one year?' But when I was growing up, Howard Hawks and Raoul Walsh and all those directors made several pictures in one year. There's no big deal. Nowadays, everybody makes a deal that you can't do it, it's an impossible feat. It wasn't an impossible feat. Some of those B movie guys would get the script on Friday night and Monday morning you're starting and here's your cast. They just went with it. It's like being a musician. If you play every day, your embouchure is strong. If you play once every two years, you have to build up all over again.

PF There is a lot of quiet subversion in your movies. The historical revisionism, challenging the conventions of the western, especially in Unforgiven, the treatment of euthanasia in Million Dollar Baby. Are you able to get away with, or to put these ideas across, because you are perceived as a conservative, an upholder of traditional views?

CE I don't know. I heard people criticise me who hadn't even seen Million Dollar Baby. I've heard people say he's done this thing about euthanasia and they'd get all upset. I'd go - wait a second, have you seen the picture? Are you interested in the people? Are you interested in the plight of a man who has never had a relationship with the daughter he wanted to have a relationship with? There'd been something in their history that has been negative and he finally finds the surrogate daughter that he loves desperately and then loses her. Did they really analyse the circumstances? No - so they make a critical judgment. If you analyse the circumstance then it becomes an interesting challenge.

I'm not really conservative. I'm conservative on certain things. I believe in less government. I believe in fiscal responsibility and all those things that maybe Republicans used to believe in but don't any more. Consequently, I think the difference in my country, the difference in the parties, is there's no difference. There are just a lot of people trying to keep their jobs. I'm cynical in that aspect.

I think I can make them [challenging movies] because I do them boldly and because I'm at an age where ... what can they do to me? Once you're past 70, what the hell can they do to you?

You just go ahead and do it. If you put your toe in the water, it's not going to work. You have to jump in.

PF You just spoke about your age. How did you feel about the physical toll and the challenge of it as you were about to embark on this project, with the budgets, the locations, large complicated scripts?

CE No problem. I felt fine. I was in a good physical and mental condition. I have the advantage of a lot of years of experience, and if I can't put it together, then I should not be doing it. You have to feel confident. If you don't, then you're going to be hesitant and defensive, and there'll be a lot of things working against you. In my career as a director, there's always been some point where you get halfway through it, or three-quarters, and you go: what is this thing all about and why am I telling the story. Does anybody really care about seeing this? At that time you have to say: OK, forget that and just go ahead. What were your first impressions, all the things you remember when you fell in love with the project? Put your head down and continue. You can never look back. I don't have that now. I had that maybe 15, 20 years ago. I'd get that moment, the reflective moment. It would come and pass real quickly but now I know it's going to be there, so I don't pay any attention to it. It's just a little bird talking. You just say: get out.

PF Which of the directors from the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood would you most have liked to work with and will regret not having worked with?

CE When I came into the business in the Fifties, a lot of those people were starting to retire. I knew Billy Wilder socially and would have loved to work with him. I did work with Bill Wellman on the Second World War film Lafayette Escadrille. I would have liked to work with Mr [Howard] Hawks and Mr [Raoul] Walsh. I once talked to Alfred Hitchcock about working with him. He had a screenplay in mind but he was just in retirement. I asked: when does he want to do this? They said: well, he's probably not going to do the picture - he's just at that stage where he's not physically up to it. I said: OK, I'd love to go meet with him. So I did, and that was great fun. Working with Don Siegel was close to that [working with the greats] because he had worked for so many of those golden age people as second unit director. I learnt what it's like to make something out of nothing. Don used to love to tell a story about Jack Warner. He told Warner that something was too difficult. Warner looked at him and said: 'When is it not difficult? Get out there and do it.'

PF We first met 30 years ago. Would you have been surprised if someonehad said to you then that you would make 30 more movies in the next 30 years but only two of them would be westerns?

CE You're the first person who has pointed this out to me, but I'm surprised. I remember that conference very well. There were a lot of people in the western genre who are no longer with us and it was a fascinating time. I did Josey Wales, and then Pale Rider and Unforgiven. I guess, because I had done quite a few westerns in the early days, that I might have made a few more, but I got away from it in the later Seventies and Eighties, and we were doing The Escape from Alcatraz and Every Which Way But Loose and Bronco Billy. I went off in different directions.

But in 1980, I read a script called The William Munney Killings, which was the working title of Unforgiven; I thought, gee, this would be a great western, but I think I should be a little bit older to do it. And so I bought the screenplay and put it in a drawer, and then, about 1990 or 91, I thought: whatever happened to that? I read it and fell in love with it all over again, and I said that this is nice, and this should be my last western.

PF When it opened, The Outlaw Josey Wales was seen as a political film, an allegory about Vietnam and its aftermath, presented as being about the Civil War. How conscious were you of using the western in that way?

CE I was conscious of it to the extent that I thought it was different from some of the westerns I had done, where the lone person comes to town, gets into conflict. In Josey Wales, from the very beginning, the hero was a person who was a fugitive from war and from the tragedy of war, and all he wanted to do was be left alone. It seemed like the more he tried to be left alone, the more things happened around him, and he was destined to be a warrior whether he liked it or not. But yes, I tried to show, even in that film, the futility of it all. I guess nothing's different today.

PF John Wayne once said that whenever he received a script that wasn't set in the west, he always tried to imagine what it would be like as a western. Does that seem overly reductive to you and how do you react to and evaluate the scripts you come across?

CE I evaluate the scripts or the book, or whatever I'm taking the material from, on its merit. I never compare them to a western. I don't feel I'm married to the genre, though I was brought up in the west, rode some horses when I was young, and fantasised about the western, as everybody did. When I see a story, I ask: is this something I'd like to be in? Is this something I'd like to see? And if I'd like to see it, would I like to tell it?

Now, in senior years, I look at it more from a directorial standpoint. In the early days, I would have looked at a film project like Million Dollar Baby [which Eastwood directed and starred in] and first thought: is this something I'd like to be in? Whereas my first thought of Million Dollar Baby was: is this something I'd like to direct, and then [second] would I like to be in it? Because I'd just finished Mystic River [directing], I was mostly interested in being behind the camera, figuring that my retirement would be rather gradual, and then some day they'll say, get out from behind the camera, and I'll go into the sunset. But right now, I've been enjoying things the way they are.

PF How did you come across James Bradley's book Flags of Our Fathers? It obviously wasn't a film you'd see yourself as being in.

CE A friend of mine is the owner and publisher of the Carmel Pine Cone, the local newspaper in the Monterey peninsula, and he called me one day and asked: have you read this book, Flags of Our Fathers? So I read it and found in it, in a non-fictional way, what we'd done in Bridges of Madison County in a fictional way: having the child find out about their parents after they had passed away. Here was a true story of a guy who didn't know what his father did and the mystery is: why didn't his father ever confide in him about the story? Then we find it was the experience of war, and the guilt of false heroism and all kinds of stuff that made him somewhat of a recluse.

I became fascinated by that, and I tried to buy the book. But it had already been bought by DreamWorks, so I thought Steven Spielberg had some plans for this property. A couple of years after that, I was at an event and Steven came up to me and said: have you ever read Flags of Our Fathers? I told him I'd always liked the book, and he said: would you consider coming over to our company to take it over and direct it? And I said OK. The conversation was just that long. We shook hands and that was it.

PF The emotive word 'father' in the title. Is that important to you personally, in regard to the generation before you, particularly of your father, and what they went through in the Depression and the Second World War?

CE Yes. You always think of what your father did as a young man. My father wasn't in the military, but the great majority of people were at that particular time. We'd just come out of the Depression and went into the war. That's what made America such a good fighting force. It's because they were a bunch of skinny kids off of farms, and out of cities, and they weren't going to have any of this being attacked.

PF When did the idea emerge of making two movies, one from the American point of view, one from the Japanese? Was Spielberg immediately responsive ?

CE The idea occurred at a meeting between Spielberg, screenwriter Paul Haggis and myself. We were talking, philosophising, about the screenplay and how it should be done. I said: I wanted to go to Iwo Jima to look at the island: would it be it feasible to film there? It had been given back to the Japanese in the mid-Sixties, and I didn't know what to expect. We visited the governor of Tokyo - Iwo Jima comes under his jurisdiction - and he gave us approval to look at the island and feel how it was for the marines to come on that deep black sand, with 100lbs on their backs, and climb through that with people shooting at you.

At that point, I started thinking: what was it like for the defenders? I climbed into the caves, through tunnels no bigger than a fireplace, and so I became interested: what are these guys like? I started reading material on General Kuribayashi [the Japanese commander at Iwo Jima] and Baron Nishi [a tank commander]. These people had lived in America and had friends there, and with a few changes of the political structure would have remained friends.

And what's so different about Kuribayashi from every other father in every other country and every other society? Really nothing. All of a sudden, a rich story emerged that would not only be different but would maybe give us some of the communality between the young people being sent off to war, regardless of what society they're in, what culture they're from.

PF You've made two very different movies. One is about horrendous sacrifice that was part of a victory in a just war, as it was considered at the time, and is, by most people, still considered. The other film is a tragic story of defeat and the destruction of a culture. Did you see this when you were conceiving the movies?

CE Yes, I saw the possibilities of this. I wanted to tell full, separate stories and analyse what it is that defeated a group of people, the last elements of a certain mentality, a certain type of culture. The last just war. I'm sure people go into wars thinking they're just, but the Second World War was the great unification of people, because being attacked by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor changed America's mentality. There was a great division in the country then over isolationism: 'We shouldn't be bothering about the European war, that's somebody else's problem', as opposed to the other group that said: 'Yes, we should be coming to their aid.' And there we are. We go off into Korea, which was a police action, it wasn't called a war, and then Vietnam and everything. I guess the Second World War is the last war we really wanted to win.

PF In making a revisionist picture, do you think you've been harder on your own country than on the Japanese? Is there a certain imbalance?

CE No, I don't think so, because they're just different. I wouldn't call them unbalanced because I believe that the American hierarchy, as portrayed in Flags of Our Fathers, was not portrayed in a bad way. You can see the urgency because of the war-time mentality. But by the same token, you can see the sadness in it, the mass confusion of it all. But we're not showing the story of MacArthur or any of the generals or admirals of the Pacific War. We see General Kuribayashi through the eyes of a conscriptee. I don't think there's a lack of balance there; I think that it's just different. I suppose you could have told Flags of Our Fathers from the viewpoint of a military commander, and that would have been different, but these pictures are about the common man - the common man that's required to, at an average age of 19, go abroad and do all this stuff. And I'm sure that the Japanese average was similar, if not younger. The films are meant to be about them.

PF When you were making Letters From Iwo Jima, did you think that you were making not an American film but a Japanese movie? And were you influenced by your experience on the sets of the films with Sergio Leone where the director had to communicate in non-verbal ways or through translators?

CE I just approached it like I was telling a Japanese story of the Japanese people; I didn't think of it in terms of an American movie. I always thought, here's what we're doing story-wise - and I wasn't taking sides in it really. Sergio had the same obstacle as I had. He didn't speak English at all at that time, and I didn't speak Japanese. We had to communicate through interpreters and it worked out OK. The thing we had to overcome here, which Sergio didn't have to overcome, is we had to tell the story in the dialect of 65 years ago, which is a different Japanese dialect than they use now and a lot of different vocabulary. We had a few older Japanese actors, who knew of the older style and so we were aware of that. So not only am I doing it with a language I don't know, I'm doing it with a dialect I've never heard of. When we recorded the kids - because that was a real instance where [a group of children] made this live radio broadcast and sung a song for the men on Iwo Jima - we had to make sure that they learnt the dialect. It was tricky because it had never been recorded. It had only been sent out over the airwaves at that time.

PF Is there anything that has surprised or pleased you about the response you had to the two movies in both Japan and in America?

CE Yes. The response has been really good in Japan. I didn't know what it was going to be, to tell you the truth, as it's bringing this story that no Japanese studied at school. No great volumes have been written about it, and most of the veterans of Iwo Jima were just like Bradley [one of the American flag-raisers depicted in Flags of Our Fathers], only more so. They just didn't talk about it.

I never had the pleasure of meeting any of them because we couldn't find any who wanted to talk about it. It's a little bit different for the Japanese to have some gringo come in there and tell some story they have heard very little of or, for some of the older generation, that has stayed buried. The men of the Iwo Jima Association, I think, were glad to see some tribute being paid to the 21,000 men who were buried, and the 8,000-12,000 still interred in the island with no identification possible. I think they were looking for some closure, and from the letters I've gotten there seems to be an appreciation.

PF What are the war movies you've most admired in the past that have influenced you, and you would most like your films to be compared with?

CE Well, I'd like them to be not compared with anything. I'd like them to be on their own. Films I liked were always obscure little films: Lewis Milestone's A Walk in the Sun, Sam Fuller's Steel Helmet, Ted Post's Vietnam film Go Tell the Spartans. I haven't seen Milestone's All Quiet on the Western Front in many years, but it looked at the First World War from the German point of view, and maybe there's a certain similarity to Flags of Our Fathers and Letters From Iwo Jima. I'm an aficionado, like everyone else, of Akira Kurosawa. His Samurai movie Yojimbo became A Fistful of Dollars. My admiration for him as a director led me into the career I had with Leone and beyond. Circumstances. The wheel goes around.

PF A final question. If you were walking past the National Film Archives and it was burning down, and you could rush in and pick out two films to preserve for posterity, which would you choose?

CE I'd probably have to grab three: Bill Wellman's The Ox-Bow Incident, The Grapes of Wrath from John Ford and Steinbeck, and John Huston's The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

On a winning streak: Eastwood at the Oscars

1993 Won Best Director and Best Picture for Unforgiven. Nominated for Best Actor; lost out to Al Pacino for Scent of a Woman

Eastwood recalls that unlike most people he did not want to be woken at 5.30am western time with the nomination news: 'I said: "Just leave it on my machine." I don't want to be studiedly blase. Maybe if the news was bad I was afraid I'd lay there and fret or something.'

2004 Nominated for Best Director and Best Picture for Mystic River. Lost out to Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King

2005 Won Best Director and Best Picture for Million Dollar Baby. Nominated for Best Actor; lost out to Jamie Foxx for Ray

At 74 Eastwood became the oldest person to win the Best Director Oscar (having faced strong competition from Martin Scorsese for The Aviator), but showed no sign of slowing down in his acceptance speech: 'I'm just lucky to be here. Lucky to be still working. And I watched Sidney Lumet, who is 80, and I figure, I'm just a kid. I've got a lot of stuff to do yet.'

2007 Nominated for Best Director and Best Picture for Letters from Iwo Jima. He faces competition from Babel, The Queen, The Departed and Little Miss Sunshine and once again squares up to Martin Scorsese for Best Director.

He is one of only three living directors to have directed two Best Picture winners (the others are Milos Forman and Francis Ford Coppola). The only director to win three Best Movie Oscars is William Wyler.

Eastwood on acting and directing:

'I like being behind the camera instead of in front of it. I can wear what I want. Will I act again? I never say never. I'm not looking to take it easy.'

Clint's best five films chosen by Philip French

Bird (1988)

Forest Whitaker plays Charlie Parker.

The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

His first masterpiece as actor-director, a western allegory on Vietnam.

Unforgiven (1992)

Bleak revisionist western, both realistic and mythic. It won Eastwood two Oscars, for Best FIlm and Best Director.

Million Dollar Baby (2004)

Feminist boxing movie about love, ambition, ageing and family responsibilities.

Flags of Our Fathers/ Letters From Iwo Jima (2006)

A Second World War diptych, as inseparable as the first two Godfather films.

... and his most underrated: A Perfect World (1993)

A road-movie thriller set in Texas on the eve of the Kennedy assassination.

No comments:

Post a Comment