Put that in your pipe: why the Maigret novels are still worth savouring

As a six-year reissue project of the series reaches completion, Scottish author Graeme Macrae Burnet explains why Simenon’s Parisian sleuth still matters, 90 years after his first caseGraeme Macrae Burnet

The Guardian

Sat 4 Jan 2020

At the beginning of Maigret and Monsieur Charles, the 75th novel in Georges Simenon’s detective series, the celebrated inspector lines up his pipes on his desk. He plays with them for a while, arranging them into amusing shapes, before selecting one that suits his mood. He has just reached a decision on the future of his career. “He had no regrets, but even so he felt a certain sadness.”

Simenon also began his writing day by lining up his pipes on his desk, and one cannot help but wonder if, as he wrote these lines, he too felt a certain sadness. It was February 1972 and, after four decades of writing up to half a dozen novels a year, Maigret and Monsieur Charles would be his last.

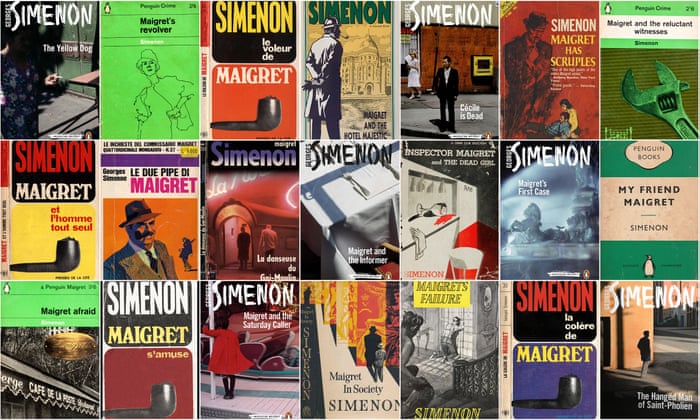

Its publication by Penguin Books later this month also marks the culmination of a six-year undertaking by the publishing house to reissue the series in its entirety, all in crisp new translations. This project has introduced a whole new audience to Simenon’s work, and provided long-standing fans with the chance to renew their acquaintance with the world of Maigret. When Simenon was asked how the Maigret novels differed from his other books – his romans durs – he described them as “sketches”. But are they more than that? Ninety years after the series was begun, are they still worth reading? Yes, and yes.

The decision Maigret has made at the beginning of the final novel is to turn down a promotion to head of the police judiciaire. “He needed to get out of his office, soak up the atmosphere and discover different worlds with each new investigation,” writes Simenon. “He needed the cafes and bars, where he so often ended up waiting, drinking a beer or a calvados.” For this is, above all, what Maigret does: he waits. And he observes. For Maigret’s mission is not merely the solving of the crimes. The apprehension of the culprit is secondary to his desire to comprehend the motivations of his opponents. In Maigret’s Childhood Friend, he tells a suspect, “I’m not judging you. I’m trying to understand.” It’s a phrase that perfectly encapsulates both Maigret’s and Simenon’s work.

At the beginning of Maigret and Monsieur Charles, the 75th novel in Georges Simenon’s detective series, the celebrated inspector lines up his pipes on his desk. He plays with them for a while, arranging them into amusing shapes, before selecting one that suits his mood. He has just reached a decision on the future of his career. “He had no regrets, but even so he felt a certain sadness.”

Simenon also began his writing day by lining up his pipes on his desk, and one cannot help but wonder if, as he wrote these lines, he too felt a certain sadness. It was February 1972 and, after four decades of writing up to half a dozen novels a year, Maigret and Monsieur Charles would be his last.

Its publication by Penguin Books later this month also marks the culmination of a six-year undertaking by the publishing house to reissue the series in its entirety, all in crisp new translations. This project has introduced a whole new audience to Simenon’s work, and provided long-standing fans with the chance to renew their acquaintance with the world of Maigret. When Simenon was asked how the Maigret novels differed from his other books – his romans durs – he described them as “sketches”. But are they more than that? Ninety years after the series was begun, are they still worth reading? Yes, and yes.

The decision Maigret has made at the beginning of the final novel is to turn down a promotion to head of the police judiciaire. “He needed to get out of his office, soak up the atmosphere and discover different worlds with each new investigation,” writes Simenon. “He needed the cafes and bars, where he so often ended up waiting, drinking a beer or a calvados.” For this is, above all, what Maigret does: he waits. And he observes. For Maigret’s mission is not merely the solving of the crimes. The apprehension of the culprit is secondary to his desire to comprehend the motivations of his opponents. In Maigret’s Childhood Friend, he tells a suspect, “I’m not judging you. I’m trying to understand.” It’s a phrase that perfectly encapsulates both Maigret’s and Simenon’s work.

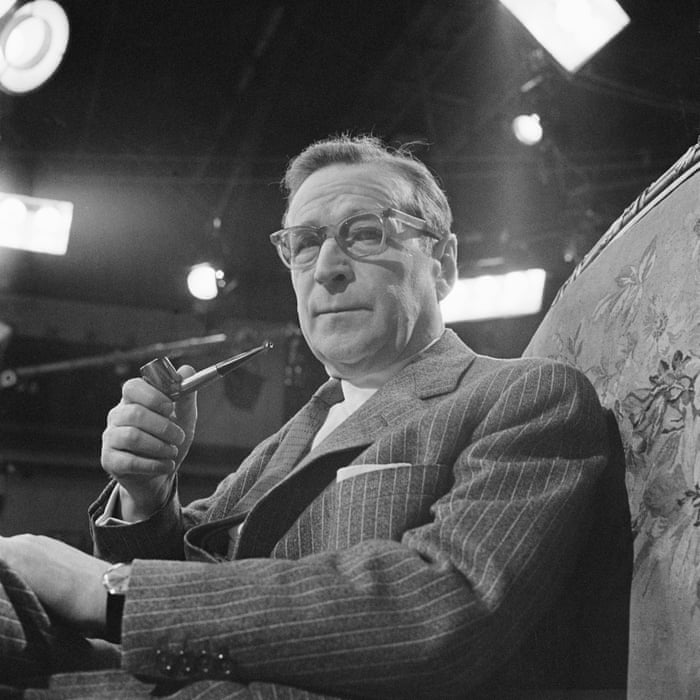

Simenon in 1962

The character of Maigret is introduced in Pietr the Latvian (1930). It’s a novel that bears some of the hallmarks of the hundreds of pulp novels Simenon had written in the previous years (a surfeit of action and exclamation marks), and this embryonic manifestation of Maigret is more of the alpha-male action hero than in the later novels: “He was a big, bony man. Iron muscles shaped his jacket sleeves. He had a way of imposing himself just by standing there.” But even at the very beginning, there was something else. Maigret has his pet theory: “Inside every wrong-doer and crook there lives a human being. What he waited and watched out for was the crack in the wall, the instant when the human being comes out from behind the opponent.”

The eponymous Pietr is an elusive figure seemingly in possession of several personalities. It is Maigret’s goal not just to gather evidence of his guilt but to break down these identities: to reach an understanding of the man. This he does through patience and observation. The climax of the novel is not the protracted chase and brawl which precedes it, but comes when the two men share a bottle of spirits in the upstairs room of an inn and Pietr unburdens himself to his confessor.

In 1948, Simenon was to provide something of a second introduction to Maigret. Maigret’s First Case predates Pietr the Latvian by some 20 years. Maigret is the 26-year-old secretary to Superintendent Le Bret of the Saint-Georges station in Paris. Simenon was by then at the height of his powers as a novelist, and the portrayal of the detective is now more nuanced. We find Maigret, the son of a Loire valley gamekeeper, cowed by the butler of a wealthy Parisian family, unsure how to act among the more seasoned cops. He is dogged, in his belief that status should not place anyone above the law, but is also riven by self-doubt and a sense of purposelessness: “Was it really a man’s work to hang around all day in a bistro, to watch a house where nothing happened?” he wonders. He recalls his early ambition to become a doctor, then more vaguely to be a kind of sage whom people consult: “a repairer of destinies, because he was able to live the lives of every sort of man, to put himself inside everybody’s mind.” This is Simenon’s supreme virtue as a novelist, to burrow beneath the surface of his characters’ behaviour; to empathise.

The plot of Maigret and Monsieur Charles concerns the murder of a wealthy playboy-lawyer, a man who like Pietr the Latvian leads a kind of double life. The prime suspect is his estranged alcoholic wife, Nathalie, a former nightclub hostess, but the question that most vexes Maigret is not that of her guilt or innocence, but that of how she can tolerate her “suffocating existence”. It is a crime novel, yes, but more than that it is an investigation into how we become what we are, and how we become entrenched in lives we might not wish to lead.

One does not read the Maigret novels in expectation of wild revelation or plot twists, but to inhabit the vividly realised world of Parisian streets, dives, bistros and high-class hotels. If the books are sketches, they are the sketches of an old master. But the thread that runs though all the books is Maigret’s inquiries into the psychology of his adversaries, and it is this unfailing humanity that makes the Maigret books truly worth reading.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/jan/04/the-enduring-depth-and-genius-of-inspector-maigret-by-graeme-macrae-burnett

No comments:

Post a Comment