Alasdair Gray obituary

Artist in words and pictures whose novel Lanark sparked a creative flowering in his native Scotland

James Campbell

The Guardian

Sun 29 Dec 2019

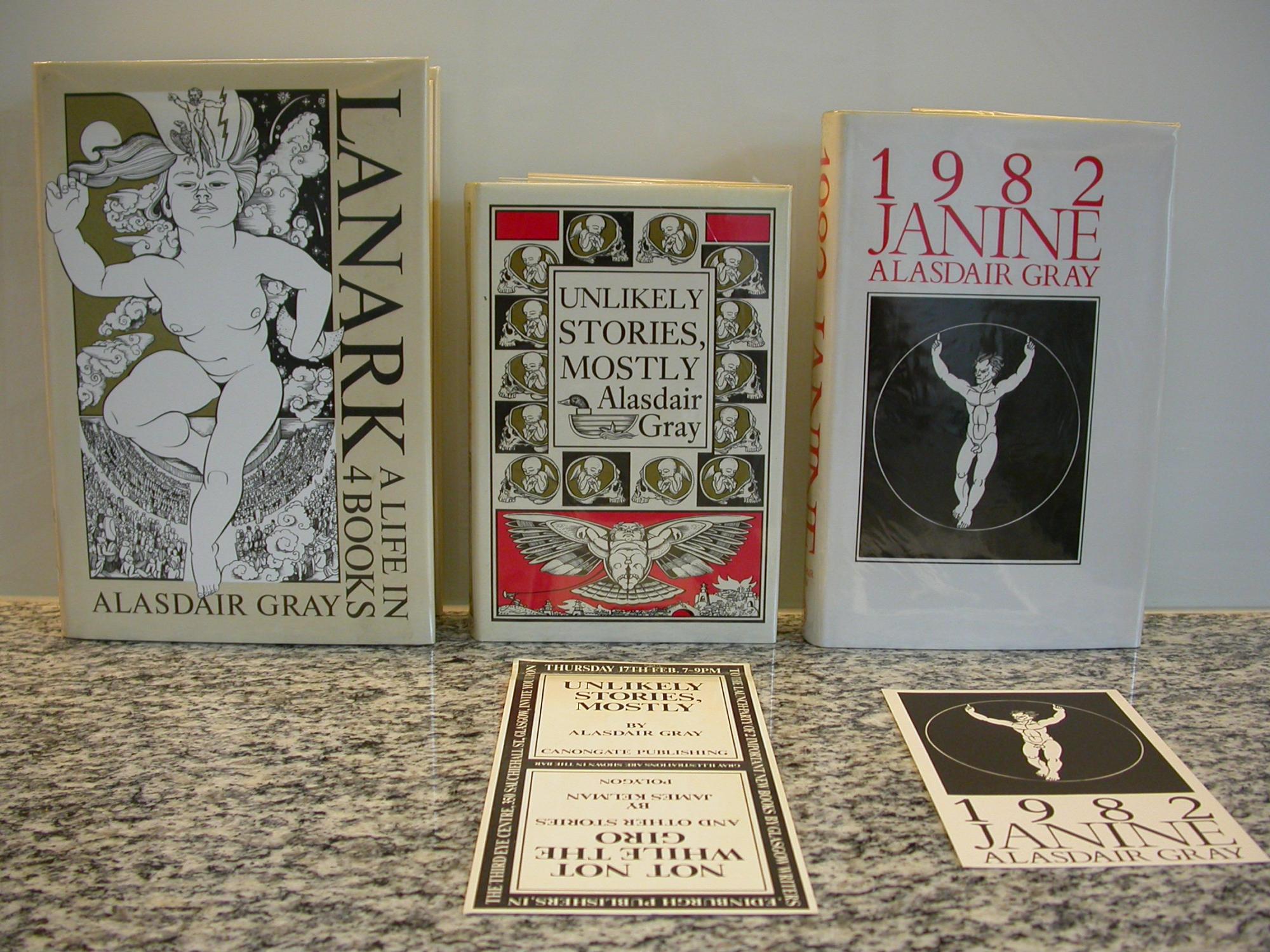

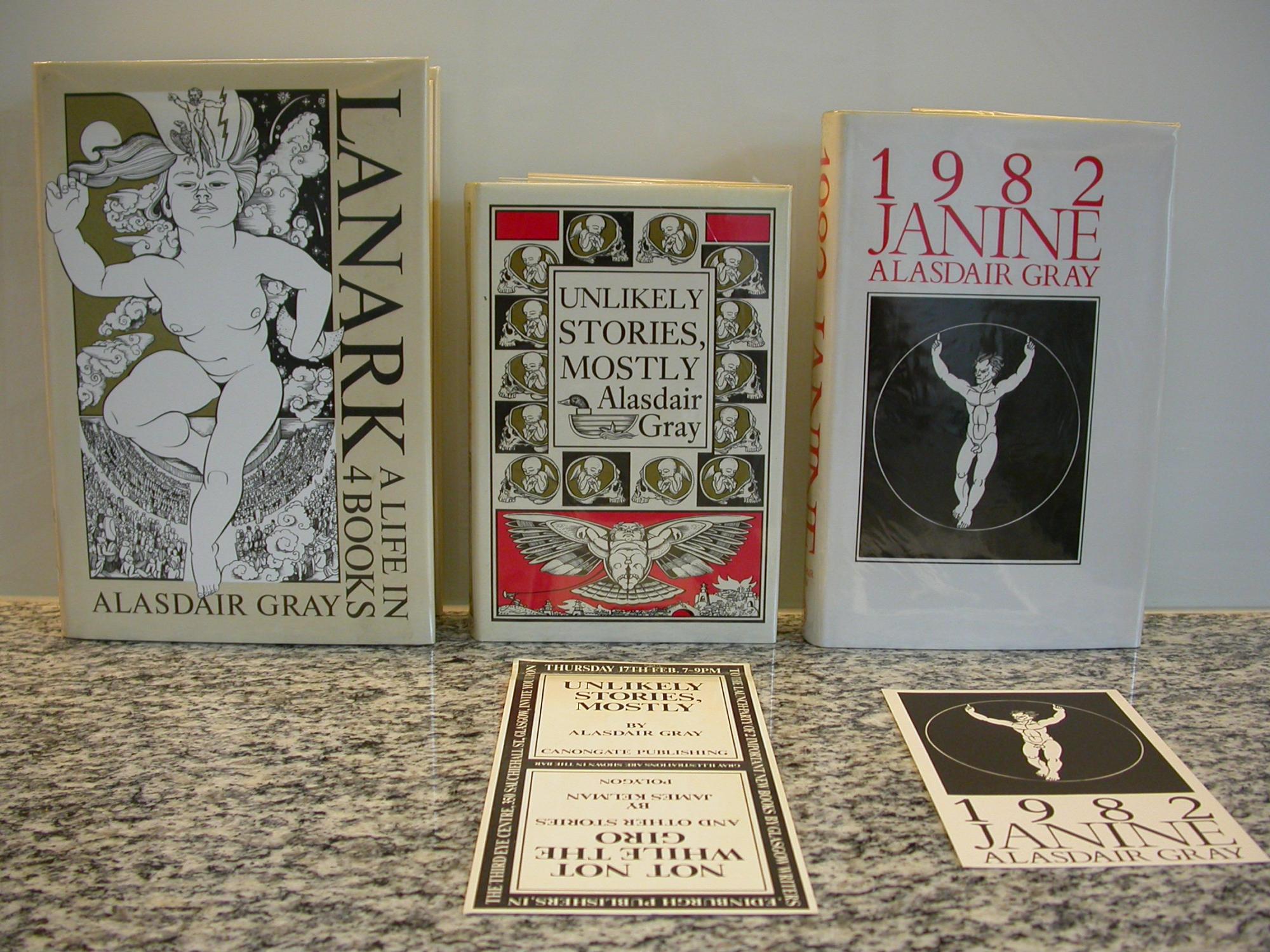

Alasdair Gray, who has died aged 85, was the father figure of the renaissance in Scottish literature and art which began in the penultimate decade of the 20th century. Gray’s great novel Lanark (1981) was an almost preposterously ambitious concoction of thinly disguised autobiography, science fiction, formal playfulness (the four-part story opened at Book Three) and graphic design by the author on a monumental scale. Scottish fiction, which had lain in a depressed state for years, suddenly took off in unexpected directions.

Irvine Welsh, Alan Warner, AL Kennedy and Janice Galloway, among others, were all Gray’s bairns. Authors invited Gray to illustrate their books. Little magazines sported his self-portraits and cursive designs on their covers. A graphic artist known locally for his eccentric appearance and behaviour became, at the age of nearly 50, a central figure of the literary world.

Born in Riddrie, in the east of Glasgow, Alasdair was the son of working-class parents with an inclination towards “Fabian, non-revolutionary socialism”. His mother Amy (nee Fleming) worked in a clothing warehouse, but nurtured a love of music, particularly opera. His father, Alexander, who ended his working life as a builder’s labourer, sought consolation in the countryside, and was a founder member of the Scottish Youth Hostels Association.

Sun 29 Dec 2019

Alasdair Gray, who has died aged 85, was the father figure of the renaissance in Scottish literature and art which began in the penultimate decade of the 20th century. Gray’s great novel Lanark (1981) was an almost preposterously ambitious concoction of thinly disguised autobiography, science fiction, formal playfulness (the four-part story opened at Book Three) and graphic design by the author on a monumental scale. Scottish fiction, which had lain in a depressed state for years, suddenly took off in unexpected directions.

Irvine Welsh, Alan Warner, AL Kennedy and Janice Galloway, among others, were all Gray’s bairns. Authors invited Gray to illustrate their books. Little magazines sported his self-portraits and cursive designs on their covers. A graphic artist known locally for his eccentric appearance and behaviour became, at the age of nearly 50, a central figure of the literary world.

Born in Riddrie, in the east of Glasgow, Alasdair was the son of working-class parents with an inclination towards “Fabian, non-revolutionary socialism”. His mother Amy (nee Fleming) worked in a clothing warehouse, but nurtured a love of music, particularly opera. His father, Alexander, who ended his working life as a builder’s labourer, sought consolation in the countryside, and was a founder member of the Scottish Youth Hostels Association.

Self Portrait, Night Street, 1953

Their efforts to hold to a life of imagination or adventure, while bound to the necessities of raising a family in an imposing industrial city, infused Gray’s own artistic vision and political instinct. He was a lifelong socialist and Scottish nationalist, who lived in the city of his birth all his life, save for a four-year spell during the second world war, when the family moved to Yorkshire.

The publication in 2010 of A Life in Pictures, a combined visual and verbal autobiography and an essential companion to Lanark, revealed not only how much of Gray’s novel was straightforwardly personal, but that the formative events of his life took place in a relatively brief period of his late teens. His mother died in 1952, before he turned 18. In the same year, he was admitted to Glasgow College of Art, despite lacking the necessary paper qualifications. There, he immediately impressed both his teachers and fellow students with fantastic, even visionary, projects; but his artistic stature was cruelly undermined by social failures, particularly involving the opposite sex.

Lanark: design for the title page, Book 4, 1982

Gray suffered from chronic eczema and an accompanying shyness which gave rise to unpredictable outbursts and an excitable delivery that remained characteristic all through his life. Lanark, like later novels including 1982, Janine (1984) and Something Leather (1990), is blistering with sexual frustration. Romantic proposals are rejected with misplaced kindliness; healthy erotic wishes are twisted into ugly shapes. The realistic portion of Lanark ends with a prostitute recoiling at the sight of the hero’s reptilian skin, which precipitates his descent to perdition.

Some of the pictures he painted at art school were still being exhibited many years later. One was Night Street Self Portrait (1953), which depicts a brooding figure in half-darkness against a background of kissing lovers and happy families. A black cat depicted nine times suggests that life is draining away. During the same period, Gray drew a remarkable Marriage Feast at Cana, in which the faces of the disciples are modelled on travellers on the Glasgow underground railway. The picture exists only in reproduction, the original having been lost after having been “left too long with a photocopying shop. When I went to collect it the firm no longer existed.”

Immediately after leaving art school, in 1958, Gray received a commission (unpaid, apart from expenses) to paint a set of murals on the subject of the Creation, in Greenhead Church of Scotland church in Glasgow. “I showed God as the third sentence of Genesis says,” Gray wrote in A Life in Pictures, “moving over the waters, not like a dove as sometimes depicted, but more like Superman.” The building was neglected over the following decade, and was demolished in 1970, leading to the loss of what Gray called “my best and biggest mural painting”. He did several other murals: in Belleisle Street synagogue, in Greenbank church, on the walls of private houses, among other places. Among the last he carried out (2012) was the 40ft mural for the entrance hall of Hillhead subway station in the West End of Glasgow. In addition to local landmarks, including the university, it has a section devoted to “All kinds of folk” – “hard workers”, “head cases”, “queer fishes” and so on, all represented in Gray’s typical witty and accessible style.

Some of the pictures he painted at art school were still being exhibited many years later. One was Night Street Self Portrait (1953), which depicts a brooding figure in half-darkness against a background of kissing lovers and happy families. A black cat depicted nine times suggests that life is draining away. During the same period, Gray drew a remarkable Marriage Feast at Cana, in which the faces of the disciples are modelled on travellers on the Glasgow underground railway. The picture exists only in reproduction, the original having been lost after having been “left too long with a photocopying shop. When I went to collect it the firm no longer existed.”

Immediately after leaving art school, in 1958, Gray received a commission (unpaid, apart from expenses) to paint a set of murals on the subject of the Creation, in Greenhead Church of Scotland church in Glasgow. “I showed God as the third sentence of Genesis says,” Gray wrote in A Life in Pictures, “moving over the waters, not like a dove as sometimes depicted, but more like Superman.” The building was neglected over the following decade, and was demolished in 1970, leading to the loss of what Gray called “my best and biggest mural painting”. He did several other murals: in Belleisle Street synagogue, in Greenbank church, on the walls of private houses, among other places. Among the last he carried out (2012) was the 40ft mural for the entrance hall of Hillhead subway station in the West End of Glasgow. In addition to local landmarks, including the university, it has a section devoted to “All kinds of folk” – “hard workers”, “head cases”, “queer fishes” and so on, all represented in Gray’s typical witty and accessible style.

Cowcaddens Streetscape in the Fifties, 1964

The impulse to write as well as draw emerged in childhood. While at art school, he began a novel called Portrait of the Artist as a Young Scot, which contained the seed that grew into Lanark, almost 30 years later. In the 1960s and 70s, he wrote plays for radio, television and the stage, including some which would later be converted into novels. The Fall of Kelvin Walker (1985), his third novel, began life as a TV play in 1968. McGrotty and Ludmilla (1990) and Mavis Belfrage (1996) had similar origins. Some 20 of these plays were later collected in A Gray Play Book (2009). It included The Cave of Polyphemus, written in 1944, when he was nine.

Many writers have had subsidiary careers at the easel, just as artists have written books. What set Gray apart was a determination to integrate the different skills in the process of bookmaking. A words-only version of Lanark, without the elaborate plates, would be tantamount to an abridged edition. His collection of tales, Unlikely Stories, Mostly (1983), was likewise lavishly decorated. In these and other instances, Gray employed motifs and images which became recognisable staples of his design: amazonian women; biblically bearded men; a foetus inside a skull; self-portraits (often showing the subject drawing the artist); doves and dogs; and always an impish figure at the end holding a sign saying “Goodbye”.

Another recurring habit was to introduce portraits of friends into his work, including the church murals. The Scottish writers James Kelman, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead, among many others, have found themselves immortalised in this way. When I asked Gray to sign a copy of his book Old Men in Love (2007), he took it and drew my portrait on the endpaper (handing it back with “Hmmm. Not very flattering”).

Faust in his Study, 1958

In 1961, Gray married Inge Sørensen, a Danish nurse then in her teens. They bought the wedding ring from a jeweller’s shop on the way to the registry office. “I believe she married me because she found me more interesting than men with steady jobs and money,” Gray stated – not out of boastfulness but as an explanation for an otherwise puzzling acceptance. He and Inge had a son, Andrew, the subject of many affectionate portraits. The couple separated after eight years and later divorced. He had a long relationship with another Danish woman, Bethsy Gray, and in the late 1980s met Morag McAlpine. They married in 1991. She died in 2014.

Even at the height of his literary and artistic success (in the autumn of 2010 there were two Gray exhibitions showing in Edinburgh at the same time), Gray feared poverty. “I am a well-known writer who cannot make a living from his writing,” he would say. Despite the status of Lanark, its sales never equalled its reputation.

The impulse to write as well as draw emerged in childhood. While at art school, he began a novel called Portrait of the Artist as a Young Scot, which contained the seed that grew into Lanark, almost 30 years later. In the 1960s and 70s, he wrote plays for radio, television and the stage, including some which would later be converted into novels. The Fall of Kelvin Walker (1985), his third novel, began life as a TV play in 1968. McGrotty and Ludmilla (1990) and Mavis Belfrage (1996) had similar origins. Some 20 of these plays were later collected in A Gray Play Book (2009). It included The Cave of Polyphemus, written in 1944, when he was nine.

Many writers have had subsidiary careers at the easel, just as artists have written books. What set Gray apart was a determination to integrate the different skills in the process of bookmaking. A words-only version of Lanark, without the elaborate plates, would be tantamount to an abridged edition. His collection of tales, Unlikely Stories, Mostly (1983), was likewise lavishly decorated. In these and other instances, Gray employed motifs and images which became recognisable staples of his design: amazonian women; biblically bearded men; a foetus inside a skull; self-portraits (often showing the subject drawing the artist); doves and dogs; and always an impish figure at the end holding a sign saying “Goodbye”.

Another recurring habit was to introduce portraits of friends into his work, including the church murals. The Scottish writers James Kelman, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead, among many others, have found themselves immortalised in this way. When I asked Gray to sign a copy of his book Old Men in Love (2007), he took it and drew my portrait on the endpaper (handing it back with “Hmmm. Not very flattering”).

Faust in his Study, 1958

In 1961, Gray married Inge Sørensen, a Danish nurse then in her teens. They bought the wedding ring from a jeweller’s shop on the way to the registry office. “I believe she married me because she found me more interesting than men with steady jobs and money,” Gray stated – not out of boastfulness but as an explanation for an otherwise puzzling acceptance. He and Inge had a son, Andrew, the subject of many affectionate portraits. The couple separated after eight years and later divorced. He had a long relationship with another Danish woman, Bethsy Gray, and in the late 1980s met Morag McAlpine. They married in 1991. She died in 2014.

Even at the height of his literary and artistic success (in the autumn of 2010 there were two Gray exhibitions showing in Edinburgh at the same time), Gray feared poverty. “I am a well-known writer who cannot make a living from his writing,” he would say. Despite the status of Lanark, its sales never equalled its reputation.

Eden and After, 1956

Moreover, any book by him threatened high production costs, and even the most indulgent of his publishers – Canongate in Edinburgh, and Cape and Bloomsbury in London, all catered to his demand for full artistic control – felt the need to pass at least some of the burden back to the author. The unearthly metropolis in which Duncan Thaw arrives after death in Lanark is called Unthank, and is not all that far removed from Glasgow in certain respects.

Gray’s pictorial autobiography contains many tales of an ungrateful city press – his church murals, like his early exhibitions, were practically ignored, if not mocked. At the beginning of the 21st century, Gray was reduced to applying to the Scottish Artists’ Benevolent Fund for money. Residual resentments were apt to surface in remarks such as: “Lanark won the publishers – not me – a design award.”

A peculiarity of Gray’s graphic work is that it sometimes appears at its best in reproduction. He himself observed that his art lacked “tactile values”. Different portraits – often gorgeous to look at, with particular attention paid to background details such as flowers in a vase or a sofa covering – tend to have similar atmospheres. A Conservative politician breathes the same air as an experimental poet. “My portraits show me as an illustrative decorator,” Gray said, in one of many perceptive comments about his own work in A Life in Pictures.

He related his definite-outline method to “fear or distrust” of “anything liable to shift or depart”. Much of his best work was executed in the spirit of friendship. As he promoted fellow writers, he enjoyed painting friends and their children. He had a likable tendency to idealise his sitters, making them appear more innocent than they were in life.

Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man (Seven Days, 2004)

In person, Gray himself presented an arresting spectacle. He had what was once described as a “benignly nutty professor” persona, with “thick spectacles and haywire hair”.

There was a high-pitched laugh which always threatened to leave mirth behind and enter the realm of mania. He would turn up for an appointment, half an hour late, in paint-stained trench-coat, with turned-up flannels flapping well above sandalled feet. Much of the time he was humorous and kind, but could snap impatiently at a remark he considered ill-thought-out, especially with reference to Scottish politics. His ideas about independence are contained in the pamphlet Why Scots Should Rule Scotland (1992).

In 1977, he was Glasgow’s official artist recorder, painting portraits and streetscapes for the People’s Palace Local History Museum. The major project of his later years – perhaps the greatest of his non-literary career – was the mural decoration of Oran Mor, an arts and leisure centre in the converted Kelvinside parish church, at the northern corner of Glasgow’s Byres Road.

Òran Mór

Sponsored by the owner, Colin Beattie, Gray began the work in 2002, lying on his back on a scaffold like a Clydeside Michelangelo, painting constellations of the zodiac in each of 12 ceiling sections. A stream of stars streaks across the central roof beam. The apse is dedicated to his favourite subject, the Creation. In is an astonishing achievement, which required the work of several assistants in addition to the artist himself.

Following a serious fall into a basement outside his home in the summer of 2015, Gray was hospitalised with a broken back, though he later returned to work. A dramatisation of Lanark by the playwright David Grieg was presented at the Edinburgh international festival that year.

His Collected Verse (2010) was followed by Every Short Story 1951-2012. Hell and Purgatory, the first two parts of his version of Dante’s Divine Comedy, “decorated and Englished in prosaic verse”, appeared in 2018 and 2019. In November Gray received the inaugural Saltire Society Scottish Lifetime Achievement award.

He is survived by Andrew and a granddaughter.

• Alasdair Gray, writer and artist, born 28 December 1934; died 29 December 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment