Friday, 31 January 2020

Wednesday, 29 January 2020

Nicholas Parsons RIP

Nicholas Parsons obituary

Popular broadcaster and television host best known for Sale of the Century and Radio 4’s Just a MinuteStephen Dixon

The Guardian

Tue 28 Jan 2020

Tue 28 Jan 2020

Nicholas Parsons, who has died aged 96, entertained the public during eight decades as a versatile actor, straight man for top television comedians and, most famously, as a quizmaster, notably of BBC Radio 4’s Just a Minute, which he chaired enthusiastically and with scarcely a break for more than 50 years.

In the show, which requires contestants to speak for 60 seconds on a given topic “without hesitation, repetition or deviation”, the persona he chose to project, honed to perfection during a career that began in the 1940s, was that of a quibbling pedant from the professional classes who felt he had to treat his unruly panellists with lofty asperity. “My manner can best be described as laborious, rather pompous,” he admitted disarmingly.

In reality he was, of course, as keen to get laughs at all costs as his charges, even – perhaps especially – if that meant robbing him of his dignity. For many years the show had the same panellists – Derek Nimmo, Kenneth Williams, Clement Freud and Peter Jones. Later regulars included Gyles Brandreth, Pam Ayres, Stephen Fry, Julian Clary, Sue Perkins, Graham Norton and Paul Merton. Only Parsons remained a constant. His longevity became the subject of much banter in recent years; an exchange on the topic “Oliver Cromwell” gives a flavour.

Parsons: “Well, it was 1653, not 1563 …”

Norton: “Nicholas remembers.”

Merton: “To be honest, he was doing the warm-up to Charles I’s execution.”

Norton: “He’s still got the bladder on a stick!”

Merton: “Unfortunately, for different reasons these days.”

What the panel could not rob him of, however, was his control and quick-wittedness. Having spent a lifetime in comedy, Parsons never failed to marvel at the show’s format. “The essence of comedy,” he told the Oldie in 2017, “is that you pause for effect, you repeat for emphasis, and you deviate to surprise. Yet these three things are exactly what you can’t do in Just a Minute. And it’s a comedy show, played for laughs.”

In many ways, the testily humorous chairman was just another character role for a performer who spent the first 20 years of his career mostly as a jobbing actor, often specialising in dialects. For the BBC Radio Drama Company in the 50s, in various productions he was an Italian waiter, a Greek seaman, an Egyptian camel-herder, a Scottish gillie, a Welsh miner, a Croatian freedom-fighter and a London taxi-driver, among many others.

Parsons was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire, the middle child of a doctor, Paul, and a former nurse, Nell (nee Maggs). He attended the kindergarten of Kesteven and Grantham school for girls, where Margaret Roberts, later Thatcher, was a pupil, and, after his father joined a medical practice in London, went to Colet Court prep school and then St Paul’s senior school.

School days were not particularly happy. He was dyslexic (then undiagnosed) and, while left-handed, was instructed by his mother to write with his right. “This can create a disturbance in the mind because one part of the brain controls your actions on the left, and another the right,” he wrote in a memoir in 2010. “If this is forcibly disrupted, it can result in difficulties in speech.”

In Parsons’s case it led to a life-long offstage stammer. Though highly intelligent, he struggled at school and compensated in two ways. He became a class clown to deflect from his hesitant progress in lessons, and because of his reading problem he developed a prodigious memory. All through his television career he never used an autocue because he could not read it. He simply remembered everything.

Although he wanted to be an actor from an early age, his parents were extremely unenthusiastic, his mother commenting: “Someone like you, Nicholas, will just end up as an alcoholic or some kind of pervert.” So when he left school he got a job as an engineering apprentice at a factory making marine pumps on Clydebank near Glasgow.

In the five years he was there he spent two six-month periods studying engineering at the University of Glasgow and also developed a variety act, impersonating film stars, which was successful and came to the attention of the impresario Carroll Levis, who used him on his radio show.

In 1944 Parsons applied to join the merchant navy but within a few days of being accepted was taken seriously ill with pleurisy and spent five months in hospital. At one point the family was told his chances of survival were 50-50. After his recovery he returned to work and qualified as a mechanical engineer, performing as an entertainer in the evenings, and when the second world war ended he became a full-time professional actor with the grudging support of his parents.

He made his West End stage debut in The Hasty Heart at the Aldwych in 1945, then played the lead in a tour of Arsenic and Old Lace. He was in rep in various towns for two years and also played supporting roles in many British films. He continued to perfect his comedy act for variety and cabaret, and in 1952 became resident comedian at the Windmill theatre.

Parsons was ubiquitous on radio and television in the 50s, and there was a breakthrough, in terms of public recognition, when he became straight man for the character comedian Arthur Haynes for 10 years in several ITV series written mostly by Johnny Speight.

Haynes usually played a wily and contemptuous tramp, and Parsons “Mr Nicholarse”, the authority figure dealing with him. The partnership broke up in 1966 and Parsons returned to the stage before working as foil for Benny Hill in more ITV shows from 1968 to 1971. He became a popular personality in his own right as quizmaster of Anglia Television’s Sale of the Century (1971-83) – “and now, from Norwich, it’s the quiz of the week”.

Parsons had been chairman of Just a Minute, devised by Ian Messiter, since the first broadcast in 1967. In 2017, as the show’s 50th anniversary approached, he concluded that: “It’s the fun that keeps it going.”

Parsons was appointed OBE in 2004 and CBE 10 years later. He served as rector at the University of St Andrews from 1988 to 1991, wrote two volumes of autobiography and performed his one-man show at the Edinburgh festival and around Britain for many years.

He is survived by his wife, Annie Reynolds, whom he married in 1995, and by two children, Suzy and Justin, from his first marriage, to the actor Denise Bryer, which ended in divorce.

Advertisement

• Christopher Nicholas Parsons, actor, comedian and quizmaster, born 10 October 1923; died 28 January 2020

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/jan/28/nicholas-parsons-obituary

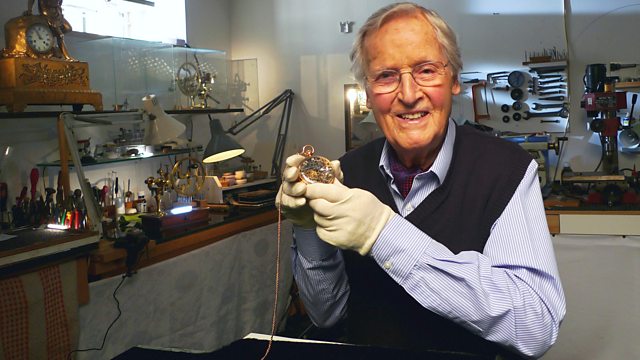

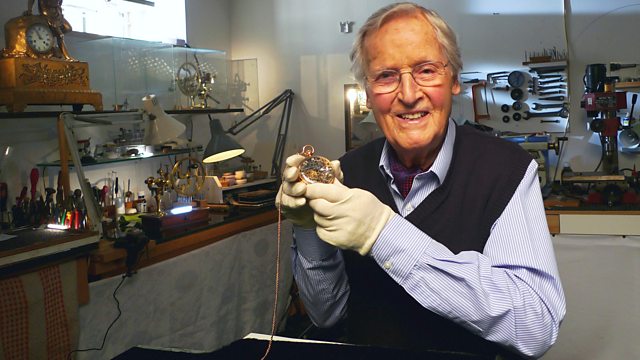

The Incredible Story of Marie Antoinette's Watch with Nicholas Parsons

Nicholas Parsons, Just a Minute host and stalwart of the entertainment world, explores his life-long enthusiasm for clocks when he goes in search of the most valuable and famous watch in the world.

The so-called Marie Antoinette, once the target of one of the biggest museum heists in history, was the masterpiece made by 18th-century genius Nicholas Breguet for that doomed queen.

Tracing the enthralling story of Breguet's rise to fame, Parsons visits Paris and Versailles, and the vaults of today's multimillion-pound Breguet business. Exploring the innovative and dazzling work of the master watchmaker, Parsons unravels the mystery behind the creation of his most precious and most brilliant work.

Parsons then heads to Israel to discover how, in the 1980s, the world's most expensive watch was stolen in a daring heist and went missing for over 20 years.

Revealing a little-known side of one of our favourite TV and radio hosts, the film offers a glimpse into Parsons's own private clock collection while also telling an enthralling tale of scientific invention, doomed decadence and daring robbery

The Incredible Story of Marie Antoinette's Watch with Nicholas Parsons

Nicholas Parsons, Just a Minute host and stalwart of the entertainment world, explores his life-long enthusiasm for clocks when he goes in search of the most valuable and famous watch in the world.

The so-called Marie Antoinette, once the target of one of the biggest museum heists in history, was the masterpiece made by 18th-century genius Nicholas Breguet for that doomed queen.

Tracing the enthralling story of Breguet's rise to fame, Parsons visits Paris and Versailles, and the vaults of today's multimillion-pound Breguet business. Exploring the innovative and dazzling work of the master watchmaker, Parsons unravels the mystery behind the creation of his most precious and most brilliant work.

Parsons then heads to Israel to discover how, in the 1980s, the world's most expensive watch was stolen in a daring heist and went missing for over 20 years.

Revealing a little-known side of one of our favourite TV and radio hosts, the film offers a glimpse into Parsons's own private clock collection while also telling an enthralling tale of scientific invention, doomed decadence and daring robbery

Monday, 27 January 2020

Sunday, 26 January 2020

Artemisia Gentileschi's Saint Catherine of Alexandria in The National Gallery

The 17th-century painter’s self-portrait, which alludes to her rape trial, is only the 20th work by a woman to enter a collection of more than 2,300 European paintings

Jonathan Jones

The Guardian

Fri 6 Jul 2018

They tried to break her on a wheel, but she survived. This is how the great female 17th-century painter Artemisia Gentileschi portrays herself in a sensational, newly uncovered masterpiece that has just been bought by the National Gallery for £3.6m – a record for her work.

Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria is a stunning collision of art and reality that sends a raw and intimate message straight from the 1600s to us. Her eyes look away, as if thinking of a painful memory, yet there is a calm in her monumental pose. She’s got the strong, muscular arms Artemisia always gave the women in her paintings and as she ponders the past, the fingers of her left hand rest on a shattered wooden wheel with vicious metal spikes embedded in its rim.

Just a few years before she painted this self-portrait, those fingers were deliberately crushed in a courtroom in Rome, when an 18-year-old Gentileschi was publicly subjected to a thumbscrew-like torture called the sibille. Cords were twisted round her fingers then pulled tight, supposedly to ensure her evidence at the trial of the man who raped her was honest.

When I saw the painting in the National Gallery’s skylit conservation workshop earlier this week, the atmosphere was intense. I was the first person from outside the gallery, since it acquired the work, to encounter the spellbinding record of her pain and courage. Just weeks ago, I had written in the Guardian about why the National Gallery urgently needs an example of this great artist’s work, so they had invited me to “come and see her”.

There’s something very special about seeing a great work of art on an easel, unframed, still with patches of surface dirt and the odd minor abrasion that will be carefully fixed before it goes on public view next year.

The painting was discovered in 2017. For centuries it had been owned by a French family, its authorship forgotten, but last December it was auctioned in Paris and bought by a London dealer. Letizia Treves, the National Gallery’s curator of baroque art, knew the museum had to have it.

This is a historic moment for the gallery. Only a tiny proportion of the art it displays is by female artists. Gentileschi’s painting has just become the 20th work by a woman to enter its collection of more than 2,300 European paintings created between the middle ages and the era of Cézanne.

As we contemplate Gentileschi’s gaze in the hidden studio, it is obvious I am not the only one who finds this an emotional moment. Treves points out the palm that Gentileschi is holding in her right hand, the symbol of her victory through martyrdom. But does this palm, wonders Treves, look like a paint brush? If so, it adds yet another autobiographical layer. They tried to break her on the wheel, but she survived to become a painter.

Larry Keith, the National Gallery’s head of conservation, who is going to restore the painting over the next six to nine months before it goes on show in 2019, points to a small patch he has already cleaned. There’s a lot of deep, subtle shadow there, he explains, that will give the painting a powerful “sculptural” quality once the remains of bad restorations and varnishes are removed.

Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593, the daughter of the painter Orazio Gentileschi. Having an artist for a father was about the only way women could get access to the training expected of artists in Renaissance and baroque Europe. Artemisia grew up in the heart of a thrilling and radical artistic subculture. Her father was a close friend of the hard-living, hard-painting Caravaggio, whose sensual, stark art blew apart convention at the end of the 1500s. As a child, Artemisia must have met Caravaggio many times. Her paintings – including this one – make plain her devotion to his art.

Fri 6 Jul 2018

They tried to break her on a wheel, but she survived. This is how the great female 17th-century painter Artemisia Gentileschi portrays herself in a sensational, newly uncovered masterpiece that has just been bought by the National Gallery for £3.6m – a record for her work.

Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria is a stunning collision of art and reality that sends a raw and intimate message straight from the 1600s to us. Her eyes look away, as if thinking of a painful memory, yet there is a calm in her monumental pose. She’s got the strong, muscular arms Artemisia always gave the women in her paintings and as she ponders the past, the fingers of her left hand rest on a shattered wooden wheel with vicious metal spikes embedded in its rim.

Just a few years before she painted this self-portrait, those fingers were deliberately crushed in a courtroom in Rome, when an 18-year-old Gentileschi was publicly subjected to a thumbscrew-like torture called the sibille. Cords were twisted round her fingers then pulled tight, supposedly to ensure her evidence at the trial of the man who raped her was honest.

When I saw the painting in the National Gallery’s skylit conservation workshop earlier this week, the atmosphere was intense. I was the first person from outside the gallery, since it acquired the work, to encounter the spellbinding record of her pain and courage. Just weeks ago, I had written in the Guardian about why the National Gallery urgently needs an example of this great artist’s work, so they had invited me to “come and see her”.

There’s something very special about seeing a great work of art on an easel, unframed, still with patches of surface dirt and the odd minor abrasion that will be carefully fixed before it goes on public view next year.

The painting was discovered in 2017. For centuries it had been owned by a French family, its authorship forgotten, but last December it was auctioned in Paris and bought by a London dealer. Letizia Treves, the National Gallery’s curator of baroque art, knew the museum had to have it.

This is a historic moment for the gallery. Only a tiny proportion of the art it displays is by female artists. Gentileschi’s painting has just become the 20th work by a woman to enter its collection of more than 2,300 European paintings created between the middle ages and the era of Cézanne.

As we contemplate Gentileschi’s gaze in the hidden studio, it is obvious I am not the only one who finds this an emotional moment. Treves points out the palm that Gentileschi is holding in her right hand, the symbol of her victory through martyrdom. But does this palm, wonders Treves, look like a paint brush? If so, it adds yet another autobiographical layer. They tried to break her on the wheel, but she survived to become a painter.

Larry Keith, the National Gallery’s head of conservation, who is going to restore the painting over the next six to nine months before it goes on show in 2019, points to a small patch he has already cleaned. There’s a lot of deep, subtle shadow there, he explains, that will give the painting a powerful “sculptural” quality once the remains of bad restorations and varnishes are removed.

Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593, the daughter of the painter Orazio Gentileschi. Having an artist for a father was about the only way women could get access to the training expected of artists in Renaissance and baroque Europe. Artemisia grew up in the heart of a thrilling and radical artistic subculture. Her father was a close friend of the hard-living, hard-painting Caravaggio, whose sensual, stark art blew apart convention at the end of the 1500s. As a child, Artemisia must have met Caravaggio many times. Her paintings – including this one – make plain her devotion to his art.

Caravaggio's Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Treves looks forward to seeing this painting hanging next to Caravaggio’s masterpieces in a few months time. It shares his raw passion for life. I see it as a dialogue with his Saint Catherine in Madrid’s Thyssen Collection. In both, there is a still, contemplative mood. Yet when you look at the sword Caravaggio’s model holds, or the spikes next to Gentileschi’s fingers, the threat of violence hangs there like a bad memory.

Gentileschi’s access to training as a painter came at a terrible price. Agostino Tassi, the painter friend her father hired as an art teacher, made ever-more menacing advances that culminated in rape. As the father of a “dishonoured” 18- year-old daughter, Orazio brought charges.

The resulting trial was a cause célèbre as witness after witness attested to Tassi’s bad character – it seemed he had previously murdered his wife. The facts of his attack on Gentileschi were clearly established, not least by her own eloquent account, where she told how she nearly stabbed him to death. Yet Tassi walked away because the Pope, for whom he was painting frescoes, protected him. It was Gentileschi’s name that was tarnished.

Gentileschi poses with the wheel, adopting the iconography of Catherine of Alexandria that had been long established by artists like Raphael (whose version is also in the National Gallery). The wheel is a symbol of suffering overcome, a reminder of violence endured.

Judith Slaying Holofernes

For us it looks like a direct allusion to her ordeal of rape, torture and humiliation. It would have had that meaning for its first audience, too. The 1612 trial made Gentileschi notorious. She painted this testimony in Florence, where she rebuilt her life and career under the patronage of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Her gory painting Judith Slaying Holofernes, which can still be seen in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, seems to fantasise revenge in its gruesome vision of a bearded man who has just woken to find one muscular woman pinioning him on his blood-spattered bed while another is halfway through hacking his head off.

No one in Gentileschi’s circles in around 1616 could be unaware of her widely publicised story. Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine is perhaps her most explicitly autobiographical work. Her famous Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, in the Royal Collection, depicts her from the side as she energetically goes to work. In the former she looks out, and we are drawn deep into her sensitive face.

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting

Artemisia is worth 10 average Old Masters. The combination of her brutalised early life and Caravaggio’s lesson that art and life are the same thing drove her to paint from a previously obscured female perspective. When she painted Judith killing Holofernes or the creepy elders spying on Susanna, she brought a personal point of view to these biblical themes. In her hands, they become studies of gender and power. She put her experience of the violent and unquestioned misogyny of her age, which meant that an 18-year-old aspiring artist was considered fodder for a sexual predator, into art that was honoured and admired by fans from the Medici to England’s Charles I.

In Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria she has truly survived. She stands by the broken wheel and defies its spikes. She proclaims her triumphant entry into a male-only profession.

Four hundred years on, that triumph is finally complete. Her vision will blaze in the National Gallery next to works by her father Orazio and her creative godfather Caravaggio. This gallery may still have pitifully few paintings by women but it matters hugely that one of them is by this truly great artist. This is one of the most important purchases the National Gallery has ever made.

Friday, 24 January 2020

Terry Jones RIP

Monty Python star whose talents were highlighted in the show that revolutionised British TV comedy

Stuart Jeffries

The Guardian

Wed 22 Jan 2020

One morning Brian Cohen, completely naked, flung open the shutters at his bedroom window to find a mob below hailing him as the Messiah. Mrs Cohen, played by Terry Jones, who has died aged 77, had something to say about that. “He’s not the Messiah. He’s a very naughty boy,” she told the disappointed crowd. It became a classic cinema moment.

The 1979 film Monty Python’s Life of Brian, a satire about an ordinary Jewish boy mistaken for the Messiah, which Jones directed and co-wrote with his fellow Pythons Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle and Michael Palin, was banned by 39 British local authorities, and by Ireland and Norway. Jones and his chums were unrepentant: they even launched a Swedish poster campaign with the slogan: “So funny it was banned in Norway.”

As for Jones’s performance as Mandy Cohen, it united two leading facets of the funnyman’s repertoire: his fondness for female impersonation, and his passion for historical revisionism. The latter was evident not just in his work for Monty Python – in which his historian’s sensibility proved essential to the satire of Arthurian England in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), which he co-directed and co-wrote – but also in several documentaries and books in which he stood up for what he took to be the misrepresented Middle Ages.

“We think of medieval England as being a place of unbelievable cruelty and darkness and superstition,” he said. “We think of it as all being about fair maidens in castles, and witch-burning, and a belief that the world was flat. Yet all these things are wrong.”

Arguably, without Jones, Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-74) would not have revolutionised British TV comedy. He was key in developing the show’s distinctively trippy, stream-of-consciousness format, where each surreal set-up (the Lumberjack Song, the upper-class twit of the year show, the dead parrot, or the fish-slapping dance) flowed into the next, unpunctuated by punchlines.

For all his directorial flair, though, Jones may well be best remembered for creating such characters as Arthur “Two Sheds” Jackson, Cardinal Biggles of the Spanish Inquisition, the Scottish poet Ewan McTeagle and the monstrous musician rodent beater in the mouse organ sketch who hits specially tuned mice with mallets.

Thanks to the show’s success, Jones was able to diversify into working as a writer, poet, librettist, film director, comedian, actor and historian. “I’ve been very lucky to have been able to act, write and direct and not have to choose just the one thing,” he said.

Jones was a second world war baby, born in Colwyn Bay, north Wales, and brought up by his mother, Dilys (nee Newnes), and grandmother, while his father, Alick Jones, was stationed with the RAF in India. He recalled meeting his father for the first time when he returned from war service: “Through plumes of steam at the end of the platform, he appeared – this lone figure in a forage cap and holding a kit bag. He ran over and kissed my mum, then my brother, then bent down and picked me up and planted one right on me. I’d only ever been kissed by the smooth lips of a lady up until that point, so his bristly moustache was quite disturbing.”

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-expressandstar-mna.s3.amazonaws.com/public/CGGXPEVAFBFHJDFG7MA5NY5ARE.jpg)

When he was four, the family moved to Surrey so his father could take up an appointment as a bank clerk. Terry attended primary school in Esher and the Royal Grammar school in Guildford. He studied English at St Edmund Hall, Oxford, and developed a lifelong interest in medieval history as a result of reading Chaucer.

At Oxford, he started the Experimental Theatre Company with his friend and contemporary Michael Rudman, performing everything from Brecht to cabaret. He also met Palin and the historian Robert Hewson, and collaborated with them on a satire on the death penalty called Hang Down Your Head and Die. It was set in a circus ring, with Jones playing the condemned man. He and Palin then worked together on the Oxford Revue, a satirical sketch show they performed at the 1964 Edinburgh festival, where he met David Frost as well as Chapman, Idle and Cleese.

After graduation, he was hired as a copywriter for Anglia Television and then taken on as a script editor at the BBC, where he worked as joke writer for BBC2’s Late Night Line-Up (1964-72). Jones and Palin became fixtures on the booming TV satire scene, writing for, among other BBC shows, The Frost Report (1966-67) and The Kathy Kirby Show (1964), as well as the ITV comedy sketch series Do Not Adjust Your Set (1967-69).

In 1967, he and Palin were invited to write and perform for Twice a Fortnight, a BBC sketch show that provided a training ground not only for a third of the Pythons (Jones and Palin), but two-thirds of the Goodies (Graeme Garden and Bill Oddie) and the co-creator of the 1980s political sitcom Yes Minister, Jonathan Lynn.

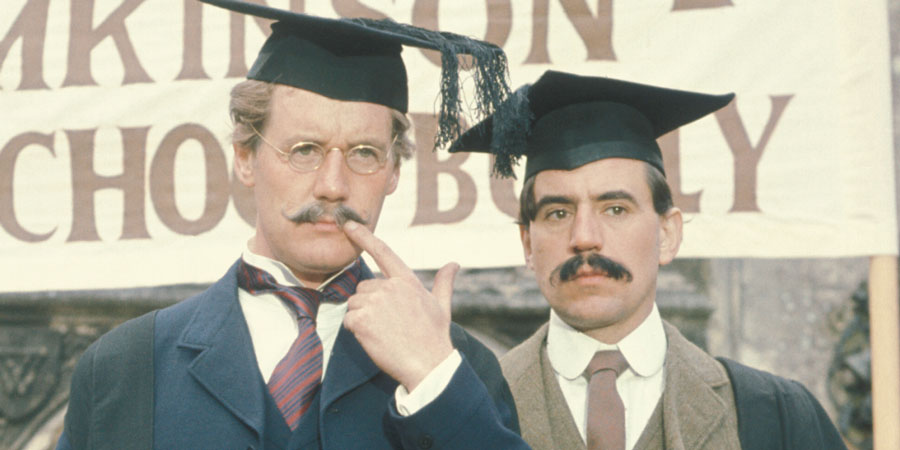

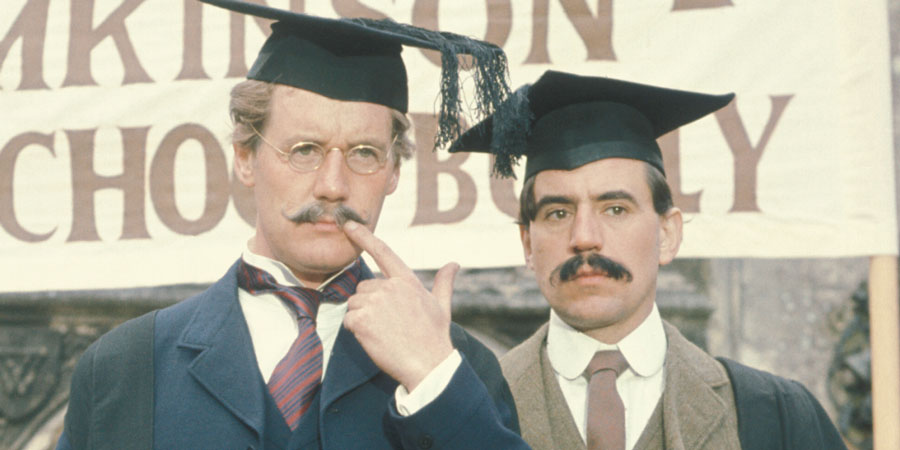

Jones and Palin wrote and starred in The Complete and Utter History of Britain (1969) for LWT. Its conceit was to relate historical incidents as if TV had existed at the time. In one sketch, Samuel Pepys was a chat show host; in another, a young couple of ancient Britons looking for their first home were shown around the brand-new Stonehenge. “It’s got character, charm – and a slab in the middle,” said the estate agent.

In the same year, he became one of the six founders of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. They expected the show to be quickly decommissioned by BBC bosses. “Every episode we’d be there biting our nails hoping someone might find it funny. Right up until the middle of the second series John Cleese’s mum was still sending him job adverts for supermarket managers cut out from her local newspaper,” Jones recalled. “It was only when they started receiving sackfuls of correspondence from school kids saying they loved it that we knew we were saved.”

After Python finished its run on TV, Jones went on to direct several films with the troupe. The first, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, was, he recalled, “a disaster when we first showed it. The audiences would laugh for the first five minutes and then silence, nothing. So we re-cut it. Then we’d show it in different cities, saying, ‘We’re worried about our film, would you come and look at it?’ And as a result people would come and they’d all be terribly worried about it too, so it was a nightmare.”

He had more fun co-writing and directing two series for the BBC called Ripping Yarns (1976-79) in which Palin starred as a series of heroic characters in mock-adventure stories, among them Across the Andes by Frog, and Roger of the Raj, sending up interwar literature aimed at schoolboys.

Jones directed and starred in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, which some religious groups denounced for supposedly mocking Christianity. Jones defended the film: “It wasn’t about what Christ was saying, but about the people who followed him – the ones who for the next 2,000 years would torture and kill each other because they couldn’t agree on what he was saying about peace and love.”

In 1983 he directed Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, in which he made, perhaps, his most disgusting appearance, as Mr Creosote, a ludicrously obese diner, who is served dishes while vomiting repeatedly.

During this decade Jones diversified, proving there was life after Python. In 1980, he published Chaucer’s Knight: The Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary, arguing that the supposed paragon of Christian virtue could be demonstrated to be, if one studied the battles Chaucer claimed he was involved in, a typical, perhaps even vicious, mercenary. He also set out to overturn the idea of Richard II presented in the work of Shakespeare “who paints him more like sort of a weak … unmanly character”. Jones portrayed the king as a victim of spin: “There’s a possibility that Richard was actually a popular king,” he said.

He wrote children’s books, starting with The Saga of Erik the Viking (1983), which he composed originally for his son, Bill. A book of rhymes, The Curse of the Vampire’s Socks (1989), featured such characters as the Sewer Kangaroo and Moby Duck.

In 1987, he directed Personal Services, a film about the madam of a suburban brothel catering for older men, starring Julie Walters. The story was inspired by the experiences of the Streatham brothel-keeper Cynthia Payne. Jones proudly related that three of four films banned in Ireland were directed by him – The Life of Brian, The Meaning of Life and Personal Services.

Two years later, he directed Erik the Viking, a film adaptation of his book, with Tim Robbins in the title role of a young Norseman who declines to go into the family line of raping and pillaging. In 1996, he adapted Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows for the big screen, giving himself the role of Mr Toad, with Ratty and Mole played by Idle and Steve Coogan. But it was rarely screened in cinemas. “It was ruined by studio politicking between Disney and Columbia Tristar,” he said. “We made a really nice film but no one saw it. It didn’t make any money, even though it was well reviewed.”

Jones was also unfortunate with his next film project. Absolutely Anything, based on a script he wrote with the screenwriter Gavin Scott, concerned aliens coming to Earth and giving one person absolute power. Plans were scuppered when a movie with a similar premise, Bruce Almighty, starring Jim Carrey, was released in 2003. Only in 2015 did Jones manage to film Absolutely Anything, in which Simon Pegg, playing a mild-mannered schoolteacher, is given miraculous powers by a council of CGI aliens voiced by Jones and his former Monty Python colleagues. Robin Williams, in one of his last roles, voiced Pegg’s dog.

Jones made well-received history documentaries, including in 2002 The Hidden History of Egypt, The Hidden History of Rome and The Hidden History of Sex & Love, in which he examined the diets, hygiene, careers, sex lives and domestic arrangements of the ancient world, often appearing in the films as an ancient character, sometimes dressed as a woman.

In his book Who Murdered Chaucer? (2003), he wondered if the poet had been killed on behalf of King Henry IV for being politically troublesome.

He wrote for the Guardian, about the poll tax, nuclear power and the ozone layer. He became a vocal opponent of the Iraq war, and his articles on the subject were collected under the title Terry Jones’s War on the War on Terror (2004).

In his 2006 BBC series Barbarians, Jones sought to show that supposedly primitive Celts and savage Goths were nothing of the kind and that the ancient Greeks and Persians were neither as ineffectual nor as effete as the ancient Romans supposed. Best of all, he sought to demonstrate that it was not the Vandals and other north European tribes who destroyed Rome but Rome itself, thanks to the loss of its African tax base.

When Jones was asked what he would like on his tombstone, he did not want to be remembered as a Python, perhaps surprisingly, but for his writing and historical work. “Maybe a description of me as a writer of children’s books or maybe as the man who restored Richard II’s reputation. I think those are my best bits.”

In 2016, it was announced that Jones had been diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia, a form of dementia that impairs the ability to communicate. He and his family and friends spoke about his experiences to help others living with the condition.

Jones is survived by his second wife, Anna (nee Söderström), whom he married in 2012, and their daughter, Siri; and by Bill and Sally, the children of his first marriage, to Alison Telfer, which ended in divorce.

• Terence Graham Parry Jones, writer, actor and director, born 1 February 1942; died 21 January 2020

Wed 22 Jan 2020

One morning Brian Cohen, completely naked, flung open the shutters at his bedroom window to find a mob below hailing him as the Messiah. Mrs Cohen, played by Terry Jones, who has died aged 77, had something to say about that. “He’s not the Messiah. He’s a very naughty boy,” she told the disappointed crowd. It became a classic cinema moment.

The 1979 film Monty Python’s Life of Brian, a satire about an ordinary Jewish boy mistaken for the Messiah, which Jones directed and co-wrote with his fellow Pythons Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle and Michael Palin, was banned by 39 British local authorities, and by Ireland and Norway. Jones and his chums were unrepentant: they even launched a Swedish poster campaign with the slogan: “So funny it was banned in Norway.”

As for Jones’s performance as Mandy Cohen, it united two leading facets of the funnyman’s repertoire: his fondness for female impersonation, and his passion for historical revisionism. The latter was evident not just in his work for Monty Python – in which his historian’s sensibility proved essential to the satire of Arthurian England in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), which he co-directed and co-wrote – but also in several documentaries and books in which he stood up for what he took to be the misrepresented Middle Ages.

“We think of medieval England as being a place of unbelievable cruelty and darkness and superstition,” he said. “We think of it as all being about fair maidens in castles, and witch-burning, and a belief that the world was flat. Yet all these things are wrong.”

Arguably, without Jones, Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-74) would not have revolutionised British TV comedy. He was key in developing the show’s distinctively trippy, stream-of-consciousness format, where each surreal set-up (the Lumberjack Song, the upper-class twit of the year show, the dead parrot, or the fish-slapping dance) flowed into the next, unpunctuated by punchlines.

For all his directorial flair, though, Jones may well be best remembered for creating such characters as Arthur “Two Sheds” Jackson, Cardinal Biggles of the Spanish Inquisition, the Scottish poet Ewan McTeagle and the monstrous musician rodent beater in the mouse organ sketch who hits specially tuned mice with mallets.

Thanks to the show’s success, Jones was able to diversify into working as a writer, poet, librettist, film director, comedian, actor and historian. “I’ve been very lucky to have been able to act, write and direct and not have to choose just the one thing,” he said.

Jones was a second world war baby, born in Colwyn Bay, north Wales, and brought up by his mother, Dilys (nee Newnes), and grandmother, while his father, Alick Jones, was stationed with the RAF in India. He recalled meeting his father for the first time when he returned from war service: “Through plumes of steam at the end of the platform, he appeared – this lone figure in a forage cap and holding a kit bag. He ran over and kissed my mum, then my brother, then bent down and picked me up and planted one right on me. I’d only ever been kissed by the smooth lips of a lady up until that point, so his bristly moustache was quite disturbing.”

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-expressandstar-mna.s3.amazonaws.com/public/CGGXPEVAFBFHJDFG7MA5NY5ARE.jpg)

When he was four, the family moved to Surrey so his father could take up an appointment as a bank clerk. Terry attended primary school in Esher and the Royal Grammar school in Guildford. He studied English at St Edmund Hall, Oxford, and developed a lifelong interest in medieval history as a result of reading Chaucer.

At Oxford, he started the Experimental Theatre Company with his friend and contemporary Michael Rudman, performing everything from Brecht to cabaret. He also met Palin and the historian Robert Hewson, and collaborated with them on a satire on the death penalty called Hang Down Your Head and Die. It was set in a circus ring, with Jones playing the condemned man. He and Palin then worked together on the Oxford Revue, a satirical sketch show they performed at the 1964 Edinburgh festival, where he met David Frost as well as Chapman, Idle and Cleese.

After graduation, he was hired as a copywriter for Anglia Television and then taken on as a script editor at the BBC, where he worked as joke writer for BBC2’s Late Night Line-Up (1964-72). Jones and Palin became fixtures on the booming TV satire scene, writing for, among other BBC shows, The Frost Report (1966-67) and The Kathy Kirby Show (1964), as well as the ITV comedy sketch series Do Not Adjust Your Set (1967-69).

In 1967, he and Palin were invited to write and perform for Twice a Fortnight, a BBC sketch show that provided a training ground not only for a third of the Pythons (Jones and Palin), but two-thirds of the Goodies (Graeme Garden and Bill Oddie) and the co-creator of the 1980s political sitcom Yes Minister, Jonathan Lynn.

Jones and Palin wrote and starred in The Complete and Utter History of Britain (1969) for LWT. Its conceit was to relate historical incidents as if TV had existed at the time. In one sketch, Samuel Pepys was a chat show host; in another, a young couple of ancient Britons looking for their first home were shown around the brand-new Stonehenge. “It’s got character, charm – and a slab in the middle,” said the estate agent.

In the same year, he became one of the six founders of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. They expected the show to be quickly decommissioned by BBC bosses. “Every episode we’d be there biting our nails hoping someone might find it funny. Right up until the middle of the second series John Cleese’s mum was still sending him job adverts for supermarket managers cut out from her local newspaper,” Jones recalled. “It was only when they started receiving sackfuls of correspondence from school kids saying they loved it that we knew we were saved.”

After Python finished its run on TV, Jones went on to direct several films with the troupe. The first, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, was, he recalled, “a disaster when we first showed it. The audiences would laugh for the first five minutes and then silence, nothing. So we re-cut it. Then we’d show it in different cities, saying, ‘We’re worried about our film, would you come and look at it?’ And as a result people would come and they’d all be terribly worried about it too, so it was a nightmare.”

He had more fun co-writing and directing two series for the BBC called Ripping Yarns (1976-79) in which Palin starred as a series of heroic characters in mock-adventure stories, among them Across the Andes by Frog, and Roger of the Raj, sending up interwar literature aimed at schoolboys.

Jones directed and starred in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, which some religious groups denounced for supposedly mocking Christianity. Jones defended the film: “It wasn’t about what Christ was saying, but about the people who followed him – the ones who for the next 2,000 years would torture and kill each other because they couldn’t agree on what he was saying about peace and love.”

In 1983 he directed Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, in which he made, perhaps, his most disgusting appearance, as Mr Creosote, a ludicrously obese diner, who is served dishes while vomiting repeatedly.

During this decade Jones diversified, proving there was life after Python. In 1980, he published Chaucer’s Knight: The Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary, arguing that the supposed paragon of Christian virtue could be demonstrated to be, if one studied the battles Chaucer claimed he was involved in, a typical, perhaps even vicious, mercenary. He also set out to overturn the idea of Richard II presented in the work of Shakespeare “who paints him more like sort of a weak … unmanly character”. Jones portrayed the king as a victim of spin: “There’s a possibility that Richard was actually a popular king,” he said.

He wrote children’s books, starting with The Saga of Erik the Viking (1983), which he composed originally for his son, Bill. A book of rhymes, The Curse of the Vampire’s Socks (1989), featured such characters as the Sewer Kangaroo and Moby Duck.

In 1987, he directed Personal Services, a film about the madam of a suburban brothel catering for older men, starring Julie Walters. The story was inspired by the experiences of the Streatham brothel-keeper Cynthia Payne. Jones proudly related that three of four films banned in Ireland were directed by him – The Life of Brian, The Meaning of Life and Personal Services.

Two years later, he directed Erik the Viking, a film adaptation of his book, with Tim Robbins in the title role of a young Norseman who declines to go into the family line of raping and pillaging. In 1996, he adapted Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows for the big screen, giving himself the role of Mr Toad, with Ratty and Mole played by Idle and Steve Coogan. But it was rarely screened in cinemas. “It was ruined by studio politicking between Disney and Columbia Tristar,” he said. “We made a really nice film but no one saw it. It didn’t make any money, even though it was well reviewed.”

Jones was also unfortunate with his next film project. Absolutely Anything, based on a script he wrote with the screenwriter Gavin Scott, concerned aliens coming to Earth and giving one person absolute power. Plans were scuppered when a movie with a similar premise, Bruce Almighty, starring Jim Carrey, was released in 2003. Only in 2015 did Jones manage to film Absolutely Anything, in which Simon Pegg, playing a mild-mannered schoolteacher, is given miraculous powers by a council of CGI aliens voiced by Jones and his former Monty Python colleagues. Robin Williams, in one of his last roles, voiced Pegg’s dog.

Jones made well-received history documentaries, including in 2002 The Hidden History of Egypt, The Hidden History of Rome and The Hidden History of Sex & Love, in which he examined the diets, hygiene, careers, sex lives and domestic arrangements of the ancient world, often appearing in the films as an ancient character, sometimes dressed as a woman.

In his book Who Murdered Chaucer? (2003), he wondered if the poet had been killed on behalf of King Henry IV for being politically troublesome.

He wrote for the Guardian, about the poll tax, nuclear power and the ozone layer. He became a vocal opponent of the Iraq war, and his articles on the subject were collected under the title Terry Jones’s War on the War on Terror (2004).

In his 2006 BBC series Barbarians, Jones sought to show that supposedly primitive Celts and savage Goths were nothing of the kind and that the ancient Greeks and Persians were neither as ineffectual nor as effete as the ancient Romans supposed. Best of all, he sought to demonstrate that it was not the Vandals and other north European tribes who destroyed Rome but Rome itself, thanks to the loss of its African tax base.

When Jones was asked what he would like on his tombstone, he did not want to be remembered as a Python, perhaps surprisingly, but for his writing and historical work. “Maybe a description of me as a writer of children’s books or maybe as the man who restored Richard II’s reputation. I think those are my best bits.”

In 2016, it was announced that Jones had been diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia, a form of dementia that impairs the ability to communicate. He and his family and friends spoke about his experiences to help others living with the condition.

Jones is survived by his second wife, Anna (nee Söderström), whom he married in 2012, and their daughter, Siri; and by Bill and Sally, the children of his first marriage, to Alison Telfer, which ended in divorce.

• Terence Graham Parry Jones, writer, actor and director, born 1 February 1942; died 21 January 2020

Wednesday, 22 January 2020

David Lynch - What Did Jack Do

David Lynch grills a monkey in a new short on Netflix

It’s your basic hard-boiled cop interrogation, except with a primate and an experimental master.

Charles Bramesco

Little White Lies

20 January 2020

How’s this for a Monday morning surprise: David Lynch has released his first proper new work since 2018’s disturbing yet mesmerizing “Ant Head”, and you can watch it right now. “WHAT DID JACK DO” appeared without warning today on Netflix, ripping open a portal into a surreal noir netherworld to break up the streaming binges – and just in time for Lynch’s 74th birthday!

Filmed in 2016, the 17-minute short was shown for the first time at the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in 2017 and then again at Lynch’s Festival of Disruption one year later. After floating around for a few years, the deep-pocketed benefactors at Netflix have given it a fitting home, where Lynch devotees can watch and rewatch as they obsessively search for clues unlocking its meaning.

In the short, the filmmaker portrays a tough-customer cop at a train station, interrogating a small primate that he suspects of murder. He grills the little monkey while the suspect delivers classically Lynchian non sequiturs about birds, until the animal launches into a musical number of strangulated passion and scampers away.

What it all means is anyone’s guess, as is the usual case with the sui generis work of Lynch. The familiar atmosphere of stark unease has returned, as has the elaborate background hiss of his meticulous sound design, and the faint genre signifiers that most recently informed the Twin Peaks series. It’s Lynch doing Lynch, and as long as he still have the space in the industry to do that, we can count it as a win.

Which is to say that while the short’s meaning may be inscrutable, its larger significance to the business of film is clear. Lynch subsists primarily on the generosity of institutional benefactors these days, most recently Showtime and now Netflix.

And even that is tenuous; anyone with an impression of Netflix’s business model understands that they’ve licensed this short not out of any desire to foster a culture of independent film, or even to champion the work of Lynch and his ilk. He’s a name, and the cachet attached to that name can get checks signed.

WHAT DID JACK DO is streaming now on Netflix worldwide.

How’s this for a Monday morning surprise: David Lynch has released his first proper new work since 2018’s disturbing yet mesmerizing “Ant Head”, and you can watch it right now. “WHAT DID JACK DO” appeared without warning today on Netflix, ripping open a portal into a surreal noir netherworld to break up the streaming binges – and just in time for Lynch’s 74th birthday!

Filmed in 2016, the 17-minute short was shown for the first time at the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in 2017 and then again at Lynch’s Festival of Disruption one year later. After floating around for a few years, the deep-pocketed benefactors at Netflix have given it a fitting home, where Lynch devotees can watch and rewatch as they obsessively search for clues unlocking its meaning.

In the short, the filmmaker portrays a tough-customer cop at a train station, interrogating a small primate that he suspects of murder. He grills the little monkey while the suspect delivers classically Lynchian non sequiturs about birds, until the animal launches into a musical number of strangulated passion and scampers away.

What it all means is anyone’s guess, as is the usual case with the sui generis work of Lynch. The familiar atmosphere of stark unease has returned, as has the elaborate background hiss of his meticulous sound design, and the faint genre signifiers that most recently informed the Twin Peaks series. It’s Lynch doing Lynch, and as long as he still have the space in the industry to do that, we can count it as a win.

Which is to say that while the short’s meaning may be inscrutable, its larger significance to the business of film is clear. Lynch subsists primarily on the generosity of institutional benefactors these days, most recently Showtime and now Netflix.

And even that is tenuous; anyone with an impression of Netflix’s business model understands that they’ve licensed this short not out of any desire to foster a culture of independent film, or even to champion the work of Lynch and his ilk. He’s a name, and the cachet attached to that name can get checks signed.

WHAT DID JACK DO is streaming now on Netflix worldwide.

In case you haven't seen Ant Head from 2018:

Monday, 20 January 2020

Saturday, 18 January 2020

Tullio Crali: A Futurist Life review

The Forces of the Bend, 1930

Tullio Crali: A Futurist Life review – a head-on revelation

The lifelong Italian futurist shared his peers’ obsession with planes and fast cars. But, as this riveting first UK show reveals, his radiant, humane paintings set him apart

Laura Cumming

Sun 12 Jan 2020

The Italian painter Tullio Crali ought not to be quite such a head-on revelation. After all, his astonishing vision of a solo pilot nose-diving straight into a canyon of skyscrapers, light shattering round his helmeted head, is one of the great masterpieces of futurist art. Yet this riveting survey at the Estorick Collection comes as a surprise from first to last, and not only because it is his first in Britain.

Crali (1910-2000) is a strange case, in life as in art. He grew up in Zadar, on what is now the Croatian coast, but which once belonged to Italy. His family moved to north-eastern Italy in 1922, and it was there, at the age of 15, that he created his first futurist work after reading an article about the movement.

Jonathan Monoplane (1988, detail)

Crali fell hard for the futurist manifesto, with its addiction to motion, speed, modernity and roaring machinery – from the espresso maker to the Gatling gun, the aeroplane to the hurtling motorcar, notoriously described by Marinetti, futurist leader, as “more beautiful than the victory of Samothrace”.

But Crali’s own painting of a car rushing round a bend is more sophisticated than anything by his contemporaries. The vehicle itself is long gone, leaving only the hint of a wheel among magnificent curving vectors of black, cream and red – scintillating traces of its fast departure.

And though he was as committed as his colleagues to the plane as ultimate futurist symbol, Crali’s aeropittura, as they are called, are frequently more original. A terrific painting at the start of this show, called Tricolour Wings (1932), has the plane ascending in sudden stages, scattering its target markings up through the sky like urgent thought bubbles. The plane’s geometry, repeated as if in stop-start motion, perfectly describes the sharp sensation of sudden uplift, catching at each new thermal current. And the sky around it – running all the way from hyperreal clouds to gracious, Titianesque beauty – amounts to a painted collage.

Broken Engine (1931)

Indeed, though you could never mistake him for anything else, Crali often seems the odd man out of the futurist gang. For one thing, he is a tremendous colourist. Planes rise into moonlight-blue skies or descend through lavender mists. The scarlet stripes of a biplane burn like a cigarette among pearl-grey clouds. And in a work such as Broken Engine, the polished wood of the slowing propeller shines gold against smoke and slate-blue heavens, its deco sheen ineffably glorified.

Roarings of an Aeroplane (1927)

What is more, there is an undeniably human aspect to Crali’s art. People get into the picture. There are two vast seamen at the prow of a gigantic battleship, trying to steer the ship through a storm with their muckle hands. A female figure raises her shapely arms like elegant wings and the blue air around her vibrates. He can paint the most complicated machinery – steam-driven pistons in a shipyard, or high-rising cranes – and there will be an intimation of human beings moving about below.

Assault of Motors (1968)

Crali himself kept on moving. He left Italy after the second world war for an art school in Paris, remaining there for almost a decade. His drawings of the city describe the brasseries, stairwells and metal chairs of the Jardin du Luxembourg, the shadows along the Seine embankment: Paris, in his words, as “mysterious, deep and moody”. In the 60s he quit Paris for Cairo, then back to Italy, eventually ending up in Milan.

But somehow Crali’s art stands still, as the man does not. In the late 1980s he is still painting aeroplanes as if they were brand new inventions, still showing solo pilots swooping about in glass cockpits. It is as if the international space race never happened.

And his devotion to futurism never seems to waver, even though Marinetti died in 1944 and the movement had its final meeting in 1950. It is hard to decipher Crali’s own politics from anything he wrote or painted; the curators of this show emphasise his belief in futurism as an aesthetic rather than political ideology. But the association with Mussolini’s fascism can hardly be ignored.

The Eruption (1977)

So perhaps that is why his later career lies in shadow. The Estorick is showing a number of Crali’s Sassintesi – startling collages of stones, seaweed and assorted bric-a-brac found on beaches and presented upright, on canvases. These appear entirely novel. And every now and again they hit the mark, when Crali takes some sea-carved rock and twists it out of kilter, so that it suddenly looks like a rushing futurist figure.

But he is at his best when most liberated from the movement. One of the most beautiful works in this show is a landscape of Ostia in late evening sun, as the shadows of hill and vale deepen, and rays of dying light arch between earth and sky. Translucent green patches stand for trees and clouds, and everything meets at the vanishing point of the ocean, radiant and serene – perhaps the most beautiful scene Crali ever painted.

• Tullio Crali: A Futurist Life is at the Estorick Collection, London, from 15 January until 11 April

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/jan/12/tullio-crali-a-futurist-life-estorick-collection-review

https://www.estorickcollection.com/exhibitions/tullio-crali-a-futurist-life

Friday, 17 January 2020

Wednesday, 15 January 2020

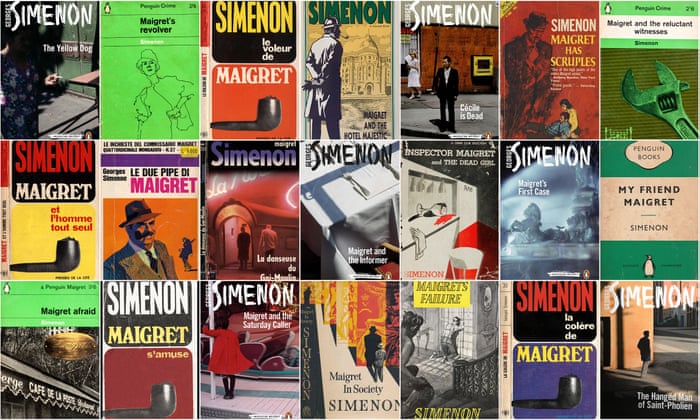

Maigret over four decades...

Put that in your pipe: why the Maigret novels are still worth savouring

As a six-year reissue project of the series reaches completion, Scottish author Graeme Macrae Burnet explains why Simenon’s Parisian sleuth still matters, 90 years after his first caseGraeme Macrae Burnet

The Guardian

Sat 4 Jan 2020

At the beginning of Maigret and Monsieur Charles, the 75th novel in Georges Simenon’s detective series, the celebrated inspector lines up his pipes on his desk. He plays with them for a while, arranging them into amusing shapes, before selecting one that suits his mood. He has just reached a decision on the future of his career. “He had no regrets, but even so he felt a certain sadness.”

Simenon also began his writing day by lining up his pipes on his desk, and one cannot help but wonder if, as he wrote these lines, he too felt a certain sadness. It was February 1972 and, after four decades of writing up to half a dozen novels a year, Maigret and Monsieur Charles would be his last.

Its publication by Penguin Books later this month also marks the culmination of a six-year undertaking by the publishing house to reissue the series in its entirety, all in crisp new translations. This project has introduced a whole new audience to Simenon’s work, and provided long-standing fans with the chance to renew their acquaintance with the world of Maigret. When Simenon was asked how the Maigret novels differed from his other books – his romans durs – he described them as “sketches”. But are they more than that? Ninety years after the series was begun, are they still worth reading? Yes, and yes.

The decision Maigret has made at the beginning of the final novel is to turn down a promotion to head of the police judiciaire. “He needed to get out of his office, soak up the atmosphere and discover different worlds with each new investigation,” writes Simenon. “He needed the cafes and bars, where he so often ended up waiting, drinking a beer or a calvados.” For this is, above all, what Maigret does: he waits. And he observes. For Maigret’s mission is not merely the solving of the crimes. The apprehension of the culprit is secondary to his desire to comprehend the motivations of his opponents. In Maigret’s Childhood Friend, he tells a suspect, “I’m not judging you. I’m trying to understand.” It’s a phrase that perfectly encapsulates both Maigret’s and Simenon’s work.

At the beginning of Maigret and Monsieur Charles, the 75th novel in Georges Simenon’s detective series, the celebrated inspector lines up his pipes on his desk. He plays with them for a while, arranging them into amusing shapes, before selecting one that suits his mood. He has just reached a decision on the future of his career. “He had no regrets, but even so he felt a certain sadness.”

Simenon also began his writing day by lining up his pipes on his desk, and one cannot help but wonder if, as he wrote these lines, he too felt a certain sadness. It was February 1972 and, after four decades of writing up to half a dozen novels a year, Maigret and Monsieur Charles would be his last.

Its publication by Penguin Books later this month also marks the culmination of a six-year undertaking by the publishing house to reissue the series in its entirety, all in crisp new translations. This project has introduced a whole new audience to Simenon’s work, and provided long-standing fans with the chance to renew their acquaintance with the world of Maigret. When Simenon was asked how the Maigret novels differed from his other books – his romans durs – he described them as “sketches”. But are they more than that? Ninety years after the series was begun, are they still worth reading? Yes, and yes.

The decision Maigret has made at the beginning of the final novel is to turn down a promotion to head of the police judiciaire. “He needed to get out of his office, soak up the atmosphere and discover different worlds with each new investigation,” writes Simenon. “He needed the cafes and bars, where he so often ended up waiting, drinking a beer or a calvados.” For this is, above all, what Maigret does: he waits. And he observes. For Maigret’s mission is not merely the solving of the crimes. The apprehension of the culprit is secondary to his desire to comprehend the motivations of his opponents. In Maigret’s Childhood Friend, he tells a suspect, “I’m not judging you. I’m trying to understand.” It’s a phrase that perfectly encapsulates both Maigret’s and Simenon’s work.

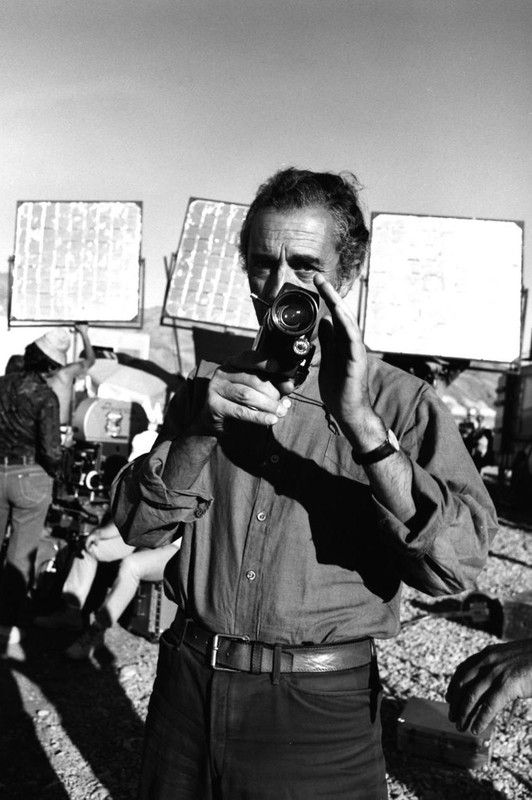

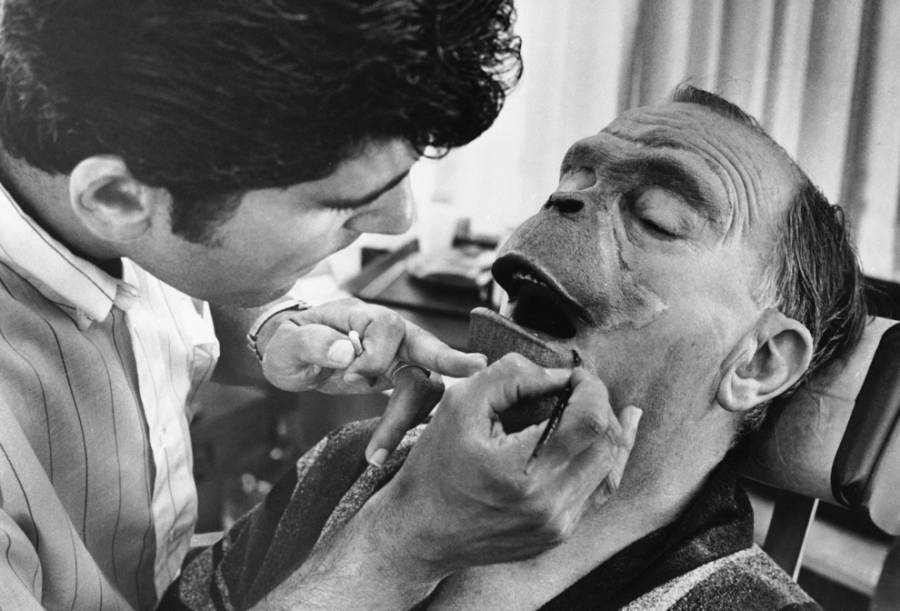

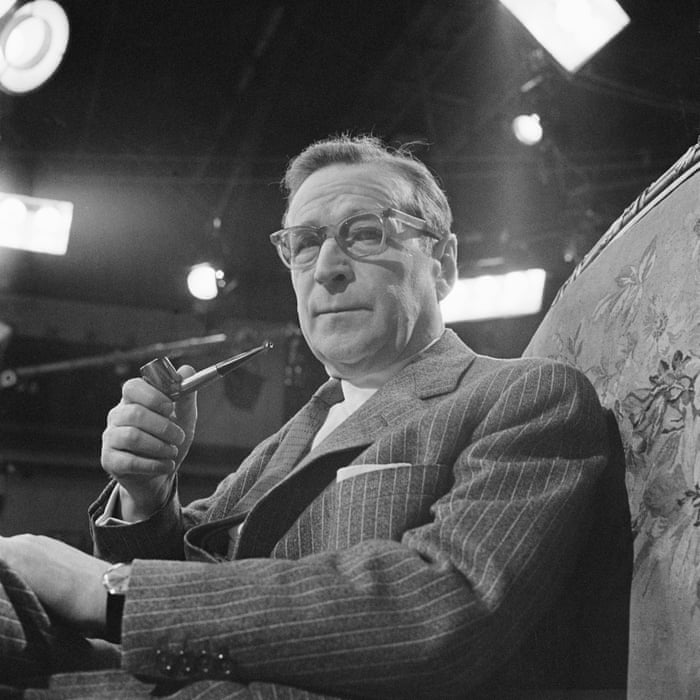

Simenon in 1962

The character of Maigret is introduced in Pietr the Latvian (1930). It’s a novel that bears some of the hallmarks of the hundreds of pulp novels Simenon had written in the previous years (a surfeit of action and exclamation marks), and this embryonic manifestation of Maigret is more of the alpha-male action hero than in the later novels: “He was a big, bony man. Iron muscles shaped his jacket sleeves. He had a way of imposing himself just by standing there.” But even at the very beginning, there was something else. Maigret has his pet theory: “Inside every wrong-doer and crook there lives a human being. What he waited and watched out for was the crack in the wall, the instant when the human being comes out from behind the opponent.”

The eponymous Pietr is an elusive figure seemingly in possession of several personalities. It is Maigret’s goal not just to gather evidence of his guilt but to break down these identities: to reach an understanding of the man. This he does through patience and observation. The climax of the novel is not the protracted chase and brawl which precedes it, but comes when the two men share a bottle of spirits in the upstairs room of an inn and Pietr unburdens himself to his confessor.

In 1948, Simenon was to provide something of a second introduction to Maigret. Maigret’s First Case predates Pietr the Latvian by some 20 years. Maigret is the 26-year-old secretary to Superintendent Le Bret of the Saint-Georges station in Paris. Simenon was by then at the height of his powers as a novelist, and the portrayal of the detective is now more nuanced. We find Maigret, the son of a Loire valley gamekeeper, cowed by the butler of a wealthy Parisian family, unsure how to act among the more seasoned cops. He is dogged, in his belief that status should not place anyone above the law, but is also riven by self-doubt and a sense of purposelessness: “Was it really a man’s work to hang around all day in a bistro, to watch a house where nothing happened?” he wonders. He recalls his early ambition to become a doctor, then more vaguely to be a kind of sage whom people consult: “a repairer of destinies, because he was able to live the lives of every sort of man, to put himself inside everybody’s mind.” This is Simenon’s supreme virtue as a novelist, to burrow beneath the surface of his characters’ behaviour; to empathise.

The plot of Maigret and Monsieur Charles concerns the murder of a wealthy playboy-lawyer, a man who like Pietr the Latvian leads a kind of double life. The prime suspect is his estranged alcoholic wife, Nathalie, a former nightclub hostess, but the question that most vexes Maigret is not that of her guilt or innocence, but that of how she can tolerate her “suffocating existence”. It is a crime novel, yes, but more than that it is an investigation into how we become what we are, and how we become entrenched in lives we might not wish to lead.

One does not read the Maigret novels in expectation of wild revelation or plot twists, but to inhabit the vividly realised world of Parisian streets, dives, bistros and high-class hotels. If the books are sketches, they are the sketches of an old master. But the thread that runs though all the books is Maigret’s inquiries into the psychology of his adversaries, and it is this unfailing humanity that makes the Maigret books truly worth reading.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/jan/04/the-enduring-depth-and-genius-of-inspector-maigret-by-graeme-macrae-burnett

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)