Robert Rauschenberg, Pearl Street Studio, c1955

Robert Rauschenberg review – six sensational decades of work finally reveal the man in full

Tate Modern, London

Driven by an insatiable curiosity, the groundbreaking artist took the triumphs and wreckage of American life and turned them into art – and this brilliant show captures his extraordinary range

Adrian Searle

The Guardian

Tuesday 29 November 2016

From first to last, Tate Modern’s Robert Rauschenberg show is almost impossibly rich and rewarding. Paintings made with dirt and paintings of nothing at all, images that encapsulate the achievements and disasters of 1960s America, a stuffed goat that looks like it has been feeding from a painter’s palette, and a mud-bath gurgling liquid cement like a lava pool. The exhibition moves through a life and career at gathering pace, from the early 1950s to the artist’s death in 2008. Room after room arrest us with yet another creative swerve, a shift in medium, scale, formal attack and presence.

Estate, 1963

In the 1950s, Rauschenberg dragged wreckage from the downtown streets of New York to his cold-water loft and made plangent, sour and lovely art that reflected his surroundings. He got Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning, whom he greatly revered, to give him a drawing so he could erase it. He used a car tyre to track a drawing across a scroll of paper, and made blank paintings of uninterrupted rollered-on whiteness that inspired his friend John Cage’s never entirely silent 4’33’, where ambient sounds fall before a silent piano. Rauschenberg’s white painting reflects only light, gathers dust, stands as mute potential. You need only do this once. He made red paintings and black paintings and paintings that combined and complicated the medium in unexpected ways. Each new move was a foil to the last, and he kept on moving.

Charlene, 1954

Rauschenberg’s early work was inspired by his surroundings, by a trip to Italy with his then lover Cy Twombly, and by the artists and poets he met at Black Mountain College in the late 1940s, including Bauhaus expatriots Josef and Anni Albers. Albers taught the relativity of visual experience – how the experience of colour, for example, was entirely dependant on its surroundings – and this relational approach stayed with Rauschenberg throughout his career. In his art, one thing always leads to another in an endless chain of relations and reactions.

Canto XIV: Circle Seven, Round 3, The Violent Against God, Nature, and Art, from the series Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno, 1959-60

Just when you think you have the measure of him, he is off again. Weaving and feinting through the years, via artistic collaborations and relationships (with Jasper Johns and Merce Cunningham, with Cage and Warhol, with dancers and scientists), stepping aside from the mainstream and going his own way, Rauschenberg stayed ahead of the pack.

Accounting for the dramatic shifts that accompanied his insatiable curiosity, the exhibition risks incoherence, or diminishing the variety of his art and preoccupations in favour of an abbreviated and smoothed-out pocket-book history. Yet the show maintains surprise, even though he was so prolific that much is missing.

Retroactive II, 1964

His art used what was around him, repurposing and recontextualising the everyday. Rauschenberg could be downbeat and beat-up, he could be slick and sharp and glossy, or move from the glutinous red paintings to the sheer, glamorous surfaces of the silkscreen paintings, with their blown up images of Jack Kennedy, old masters and astronauts. He adumbrated the flavour of his times.

Monogram, 1955-59

“What was great about the 50s,” remarked American composer Morton Feldman, “is that for one brief moment – maybe say six weeks – nobody understood art.” But somehow Rauschenberg kept definitions at bay throughout his career, allowing himself less the task of understanding than that of making. Sometimes it must have seemed as if his art almost made itself. He never tried to sew things up. That is the unenviable job of exhibitions.

Untitled (Spread), 1983

Other Rauschenberg shows have afforded a tighter view; here we see the man in full, or as near as we can get. This retrospective considers the variety and development of Rauschenberg’s art over almost six decades. While his relationships with other artists remain key, it is his own achievement that counts. Never has the phrase “losing yourself in the work”, the ego suspended, felt so appropriate as with Rauschenberg, who said he never had the equivalent of writer’s block. Even when he was caught for years in cycles of drinking and depression, the work went on: umbrellas and parachutes, full-body X-rays, dead radios and stopped clocks, tin cans, dead presidents, dances and pratfalls.

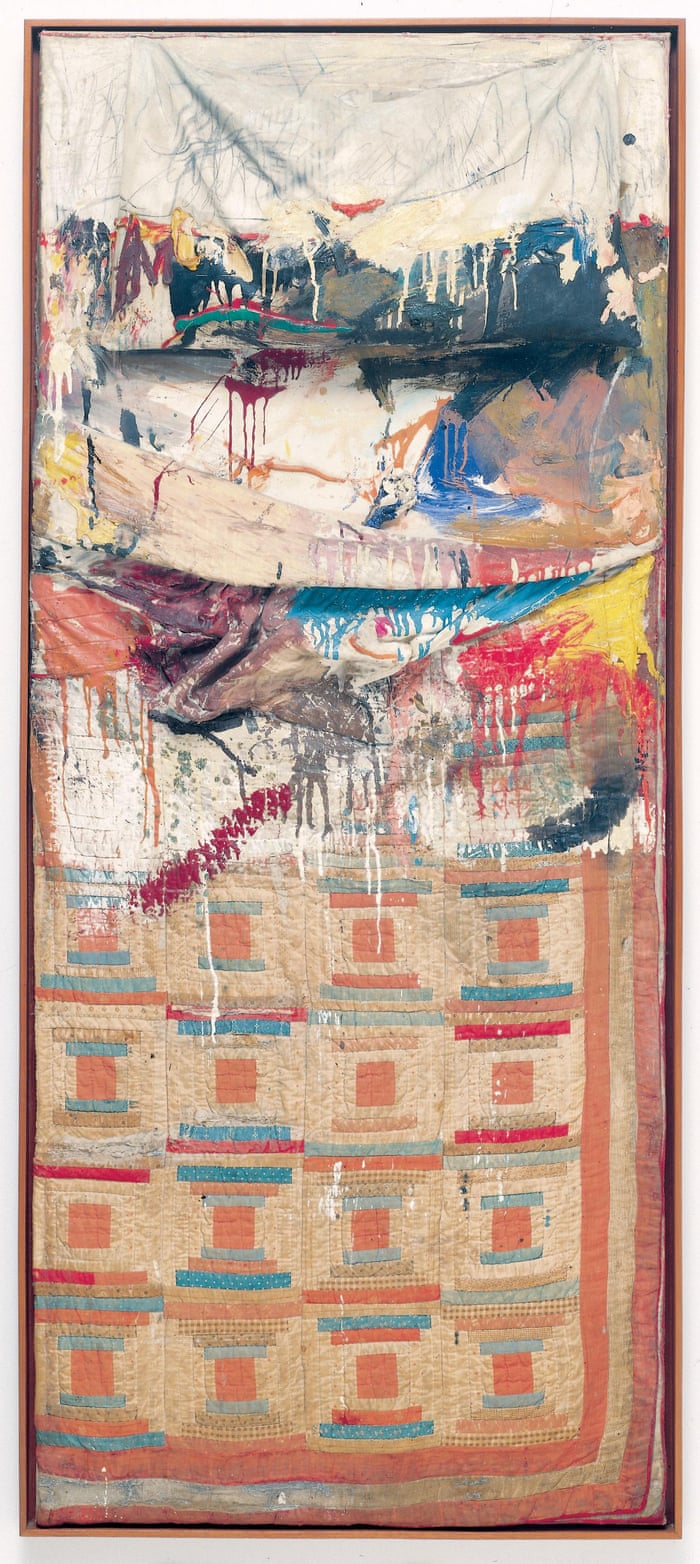

Bed, 1955

There is a painting made with a real sheet, quilt and pillow, like a gloriously squalid and filthy painter’s lie-in. He made paintings incorporating handkerchiefs, parasols; one has a plaster dog tethered to it. There are two almost identical paintings – even the paint smears and drips are the same. The same, but different. I spent ages staring from one to the other. I found myself stuttering between one moment and the next.

Another incorporates a One Way street sign, pointing out of the picture, redirecting our attention away from art and back to real life, a place where illusions end and life begins. Go on doing this sort of thing too long and the gags become boringly rhetorical. So he stopped making them.

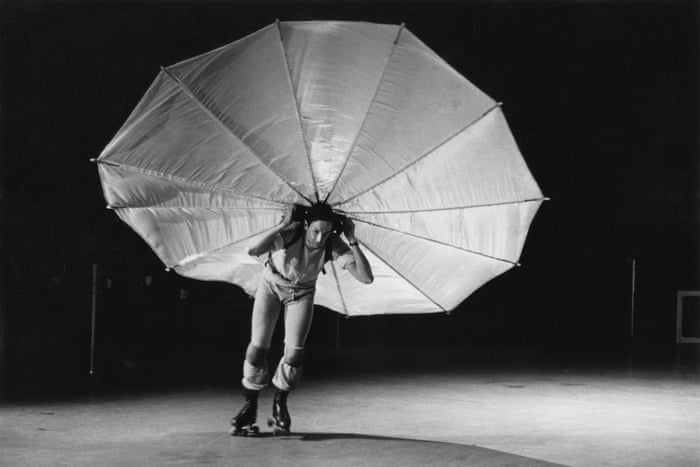

Rauschenberg’s restlessness and curiosity are invigorating. One minute he is in the studio, the next painting on stage with Merce Cunningham, or careening about in his own dance piece on roller skates, or making an artwork on a microchip to be sent into space. The filmed performances in the show are tantalising glimpses of an art that was lived.

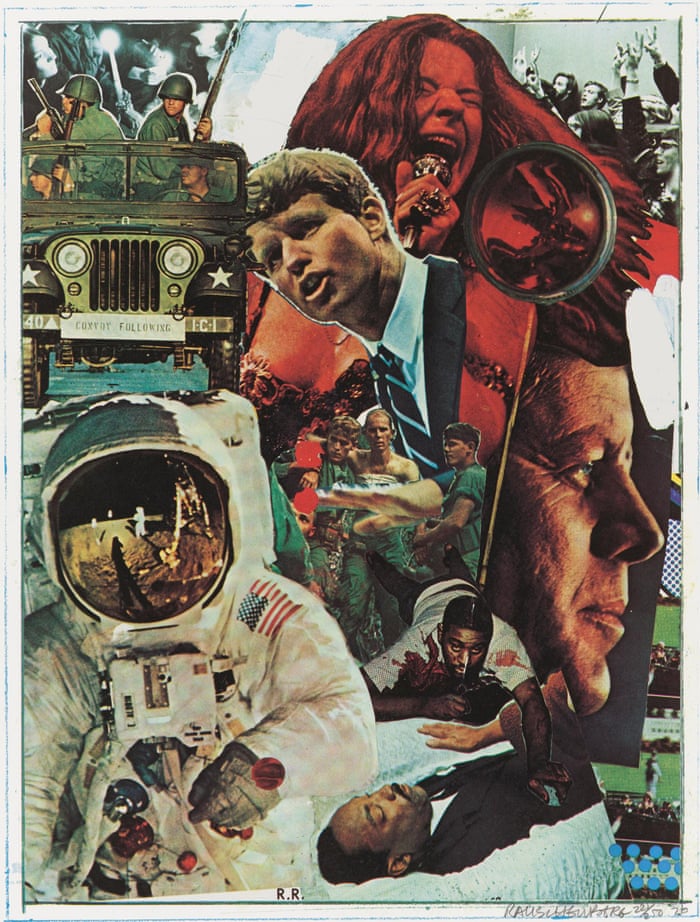

Signs, 1970

Mourning JFK, Martin Luther King and Janis Joplin, he spliced their images with borrowed images of the war in Vietnam, peace protesters and race-riots. Commissioned as a Time magazine cover in 1970, it was rejected, as if the montage were too much. It was the 60s itself that was the problem. After this comes a light-filled room of eviscerated cardboard packaging, opened-up boxes and hanging fabrics, abstractions as lovely and sparse as the earlier works were dense and complicated. Rauschenberg’s works from the 70s seem a deliberate counterpoint, as relaxed as they were terse.

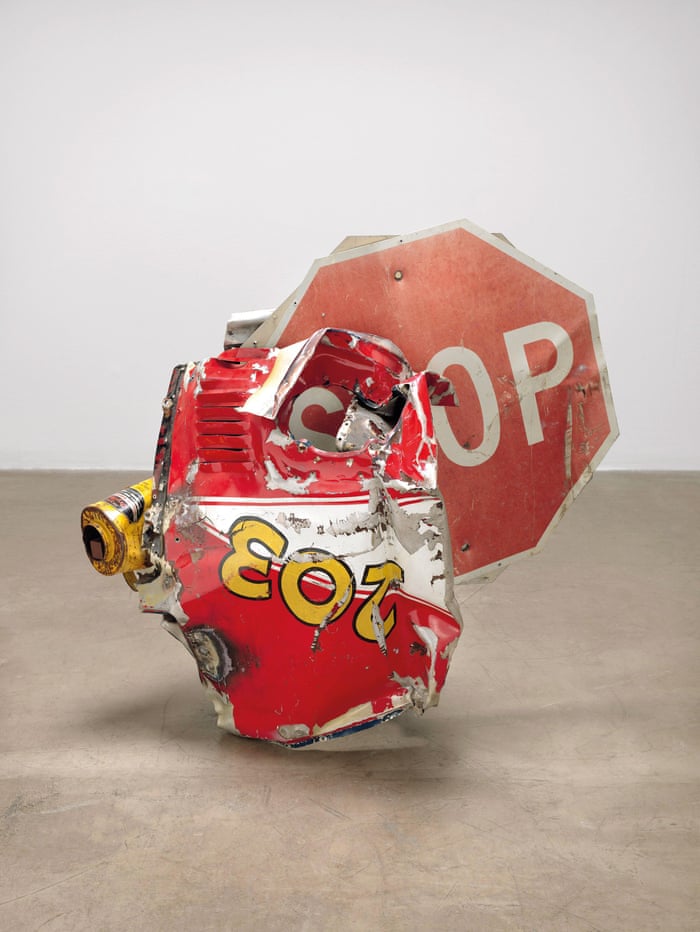

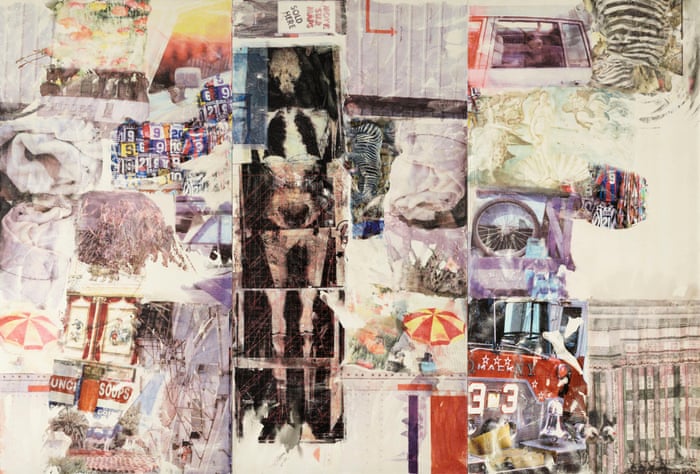

Stop Side Early Winter glut, 1987

Then he starts recomplicating things again, revving up after letting go, travelling, taking photographs, rescuing bits of mangled metal and letting them stand for themselves. The inkjet paintings in the last room, with their juddering montages of photographic imagery, both hark back to the density of his combines and silkscreen paintings, and predict the visual and mental cacophonies of the internet age, which was only just beginning in the artist’s last years.

In one late work a skeleton X-ray is surrounded and besieged by a welter of signs and snapshots: a zebra drinking, a wall calendar’s flurry of expired dates. Rauschenberg’s art is still timely. It’s time.

• Robert Rauschenberg is at Tate Modern, London, 1 December to 2 April.

• Robert Rauschenberg is at Tate Modern, London, 1 December to 2 April.

No comments:

Post a Comment