David Tindle RA: A Retrospective review – lush yet spectral

Huddersfield Art Gallery

One of the finest figurative painters of his generation, David Tindle remains unknown to many. This retrospective is long overdue

Rachel Cooke

Tindle, who now lives and works in Italy, wasn’t always unknown, of course. In a vitrine at Huddersfield Art Gallery you can see the newspaper reports that greeted his arrival on the scene in the early 50s: an angular, floppy-haired fellow who, by the critics’ account, was coming up hard on the heels of Prunella Clough, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Keith Vaughan. After a six-month stint at junior art college in Coventry and two years’ graft at a commercial art studio, Tindle had his first London exhibition aged just 19, having moved to the city to work with the theatrical scene-painter Edward Delaney (the business of painting backdrops, “working in a big flow of colour”, was to have a profound and lasting influence on his work). The exhibition changed everything. An admirer of John Minton, Tindle found the artist’s number in the telephone book and rang to invite him to see it. Minton did, and the two became friends. Also in the vitrine is Tindle’s 1952 pencil drawing of Minton, tender and reverent.

Mother and Child, 1954

Mother and Child, 1954

Through Minton, Tindle met Freud, Vaughan and the rest – older men who helped build his sense of himself as an artist. He was then “very susceptible to influence”, and you see this in the early works: Barges on the Regent’s Canal(1954, ink and watercolour on paper) shows what he learned about line from Minton; Freud exerts a clear hold on the wondrously detailed Mother and Child(1954, oil on board), a portrait of Tindle’s baby son, John, on the breast. The more abstract Paddington (1961, oil and sand on canvas) links to Frank Auerbach’s work of the same period. But already Tindle’s paintings have an extraordinary presence: there is something sacramental about the arrangement of the objects in his still lifes. Broken Egg Shell (1954, oil on board) is an extraordinary picture. At first sight it belongs to the school of William Nicholson, a study in beauty, light and shadow. But look closer and the eggshell in question seems to be out of proportion, almost planet-like on its white plate, which is itself balanced on a moonscape rather than a tablecloth. Here is the first whisper of the atmosphere that will pervade Tindle’s mature work, which plays in the most delicate way with the idea of realism.

Broken Egg Shell, 1954

Broken Egg Shell, 1954

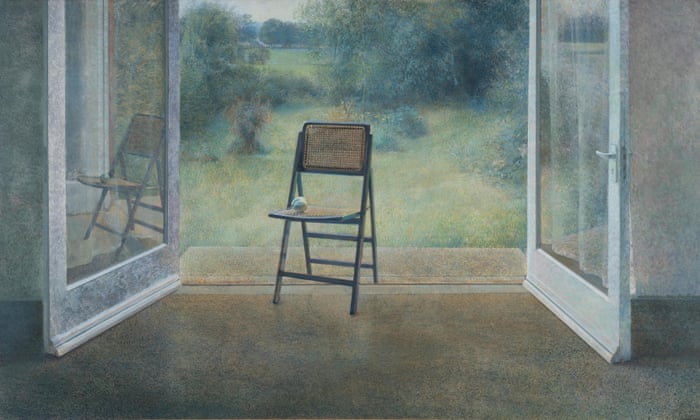

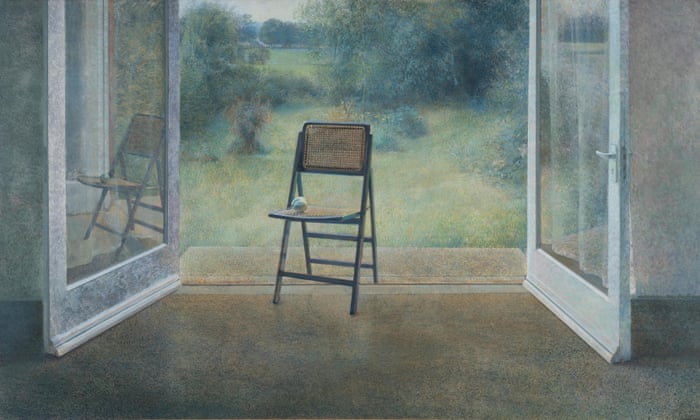

The sea change came in the early 1970s, when he swapped oil and acrylic for egg tempera, an exacting medium that helped him achieve a “crisper articulation of form”, a quality closer to a photograph. The result was, and is, stunning. He used it for still lifes and portraits (Tindle is a gorgeous, empathetic portraitist, and several are included in this show, including a study for a painting of Dirk Bogarde commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery), but its most perfect expression can be seen in the series of gardens – verdant rooms, really – that he painted through the 70s and well into the 80s: Garden, Evening (1979); Garden on the Hill, 7am (1984); Egg on a Table (1985). These have recurring motifs: doors and windows to form pictures within pictures, a theatrical framing device that may be traced back to his scenery painting days; a carefully placed chair, often featuring some kind of basketwork, and on it, perhaps, an apple. However, it’s their atmosphere, lush yet spectral, that hangs in the mind like mist.

Egg on a Table, 1985

Tindle has said that in these works “memory and presence are very close”. They are, in other words, depictions of real places, recollected in the tranquillity of the studio. I can’t really describe the powerful effect they have on me. Only the work of Michael Andrews, his near contemporary and with whom his work shares a certain tone, moves me more. The finest of them all, Garden on the Edge of the Village (1976), depicts those few moments on a cold but bright winter’s day just before dusk. We are in an allotment or cultivated field close to a farmhouse, where a small bonfire still smokes; the sky is mottled, like an old enamel mug. It is a painting that is at once both calm and urgent, an eternal scene but also a vanishing one. Tindle, you finally realise, is as interested in time as he is in place. How to capture it? Light is the key. It illuminates his work, warms it seemingly from within, humanising his extraordinary skill. But it is also a metaphor. Beyond the trees, the wall, the hedge, darkness is creeping ever closer.

David Tindle RA: A Retrospective is at Huddersfield Art Gallery until 4 February 2017

Huddersfield Art Gallery

One of the finest figurative painters of his generation, David Tindle remains unknown to many. This retrospective is long overdue

Rachel Cooke

The Guardian

Sunday 20 November 2016

Unless you live there, or close by, Huddersfield isn’t particularly easy to reach. The journey by train from Wakefield can take up to 40 minutes, the puttering two-carriage engine that works this route no match at all for the town’s magnificent neoclassical station. But never mind. Who cares about bad connections and too-weak Costa tea when at the end is one of the loveliest small exhibitions you’re likely to see this side of Brexit, and perhaps far beyond it?

Sunday 20 November 2016

Unless you live there, or close by, Huddersfield isn’t particularly easy to reach. The journey by train from Wakefield can take up to 40 minutes, the puttering two-carriage engine that works this route no match at all for the town’s magnificent neoclassical station. But never mind. Who cares about bad connections and too-weak Costa tea when at the end is one of the loveliest small exhibitions you’re likely to see this side of Brexit, and perhaps far beyond it?

Garden on the Edge of the Village, 1976

The painter David Tindle was born in Huddersfield in 1932, and though he grew up largely in Coventry, it’s this connection that has given the town’s art gallery an excuse to stage a long overdue retrospective of a career that began in the late 40s and continues still. Will this ignite new interest in him, an artist whose name is now far too little known? I hope so, and the show may yet (fingers crossed) travel. In the meantime, seek it out and you will discover, over the course of just two oblong rooms, an uncommonly exquisite painter whose sensibility, imbuing as it does the quotidian with the numinous, can be traced back to Samuel Palmer and forward to another Coventry man, George Shaw.

Baltais Dzidrais, 1979

The painter David Tindle was born in Huddersfield in 1932, and though he grew up largely in Coventry, it’s this connection that has given the town’s art gallery an excuse to stage a long overdue retrospective of a career that began in the late 40s and continues still. Will this ignite new interest in him, an artist whose name is now far too little known? I hope so, and the show may yet (fingers crossed) travel. In the meantime, seek it out and you will discover, over the course of just two oblong rooms, an uncommonly exquisite painter whose sensibility, imbuing as it does the quotidian with the numinous, can be traced back to Samuel Palmer and forward to another Coventry man, George Shaw.

Baltais Dzidrais, 1979

Tindle, who now lives and works in Italy, wasn’t always unknown, of course. In a vitrine at Huddersfield Art Gallery you can see the newspaper reports that greeted his arrival on the scene in the early 50s: an angular, floppy-haired fellow who, by the critics’ account, was coming up hard on the heels of Prunella Clough, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Keith Vaughan. After a six-month stint at junior art college in Coventry and two years’ graft at a commercial art studio, Tindle had his first London exhibition aged just 19, having moved to the city to work with the theatrical scene-painter Edward Delaney (the business of painting backdrops, “working in a big flow of colour”, was to have a profound and lasting influence on his work). The exhibition changed everything. An admirer of John Minton, Tindle found the artist’s number in the telephone book and rang to invite him to see it. Minton did, and the two became friends. Also in the vitrine is Tindle’s 1952 pencil drawing of Minton, tender and reverent.

Through Minton, Tindle met Freud, Vaughan and the rest – older men who helped build his sense of himself as an artist. He was then “very susceptible to influence”, and you see this in the early works: Barges on the Regent’s Canal(1954, ink and watercolour on paper) shows what he learned about line from Minton; Freud exerts a clear hold on the wondrously detailed Mother and Child(1954, oil on board), a portrait of Tindle’s baby son, John, on the breast. The more abstract Paddington (1961, oil and sand on canvas) links to Frank Auerbach’s work of the same period. But already Tindle’s paintings have an extraordinary presence: there is something sacramental about the arrangement of the objects in his still lifes. Broken Egg Shell (1954, oil on board) is an extraordinary picture. At first sight it belongs to the school of William Nicholson, a study in beauty, light and shadow. But look closer and the eggshell in question seems to be out of proportion, almost planet-like on its white plate, which is itself balanced on a moonscape rather than a tablecloth. Here is the first whisper of the atmosphere that will pervade Tindle’s mature work, which plays in the most delicate way with the idea of realism.

The sea change came in the early 1970s, when he swapped oil and acrylic for egg tempera, an exacting medium that helped him achieve a “crisper articulation of form”, a quality closer to a photograph. The result was, and is, stunning. He used it for still lifes and portraits (Tindle is a gorgeous, empathetic portraitist, and several are included in this show, including a study for a painting of Dirk Bogarde commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery), but its most perfect expression can be seen in the series of gardens – verdant rooms, really – that he painted through the 70s and well into the 80s: Garden, Evening (1979); Garden on the Hill, 7am (1984); Egg on a Table (1985). These have recurring motifs: doors and windows to form pictures within pictures, a theatrical framing device that may be traced back to his scenery painting days; a carefully placed chair, often featuring some kind of basketwork, and on it, perhaps, an apple. However, it’s their atmosphere, lush yet spectral, that hangs in the mind like mist.

Egg on a Table, 1985

Tindle has said that in these works “memory and presence are very close”. They are, in other words, depictions of real places, recollected in the tranquillity of the studio. I can’t really describe the powerful effect they have on me. Only the work of Michael Andrews, his near contemporary and with whom his work shares a certain tone, moves me more. The finest of them all, Garden on the Edge of the Village (1976), depicts those few moments on a cold but bright winter’s day just before dusk. We are in an allotment or cultivated field close to a farmhouse, where a small bonfire still smokes; the sky is mottled, like an old enamel mug. It is a painting that is at once both calm and urgent, an eternal scene but also a vanishing one. Tindle, you finally realise, is as interested in time as he is in place. How to capture it? Light is the key. It illuminates his work, warms it seemingly from within, humanising his extraordinary skill. But it is also a metaphor. Beyond the trees, the wall, the hedge, darkness is creeping ever closer.

David Tindle RA: A Retrospective is at Huddersfield Art Gallery until 4 February 2017

No comments:

Post a Comment