Wednesday, 30 November 2016

Tuesday, 29 November 2016

Donald Fagen Interview

Marc Myers

JazzWax

8 July 2011

Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, co-founders of Steely Dan, wrote life's soundtrack for anyone who attended college in the 1970s. Their music was adored by dorm-bound jazz heads who sought contemporary music but didn't want to give up the sound of horns and an acoustic piano. In today's Wall Street Journal (go here), I interview Mr. Fagen, catching up with him just before the start of Steely Dan's world tour last Saturday. My outtakes from our conversation are below.

In addition to original melody lines, slinky riffs and sophisticated harmonies, Steely Dan's appeal rests heavily in Fagen and Becker's lyrics. They are complex and random, in a poetic way. At times, lines seem joined just for the sake of hearing them bang against each other, like row boats roped close together.

Steely Dan's music hits jazz fans particularly hard. This may be due partly to the '70s cutlure, when jazz was played too loud and too fast by many fusion artists. The music also tends to be personal. Back then, you owned something called a stereo. Which usually meant a receiver, turntable and a pair of heavy speakers, You had to burn the plastic ends of cables to expose the wire to attach your speakers. You also needed to know how to balance your turntable's tonearm once the cartridge was attached. And then there were the many milk crates of LPs—heavy and highly organized. Music at college was a physical experience, and you were intimately involved with the records you owned.

Steely Dan was part of that scene for those who cared about music. Fagen and Becker's recording technique was pinpoint sharp, and a good stereo system teased out all of the texture. But for years, most people had no idea what Donald Fagen or Walter Becker looked like—or whether Steely Dan had a consistent band personnel. They never toured, and were reportedly highly introverted—the equivalent today, I suppose, of computer hackers.

When I told friends of a certain age a few weeks ago that I had interviewed Donald Fagen, their email answers were remarkably similar: "Fagen? A God. So envious." For years I've wanted to tell Mr. Fagen how much I appreciated Ajaand how it got me through the Boston Blizzard of '78. I finally had that chance a couple of weeks ago. Talk about closure.

Here are the outtakes from my Wall Street Journal interview with the 63-year-old Donald Fagen:

Marc Myers: Sorry to hear about the passing of Roger Nichols, your long-time engineer. For the average listener, what did he bring to your albums?

Donald Fagen: Thank you. Roger was able to execute the kind of production we were looking for in terms of sound. From the beginning in the early 1970s, Walter and I were looking for the hi-fidelity sound that you didn’t hear too much in rock music at the time. Roger was familiar with the jazz records that Walter and I used to listen to growing up. Roger taught us about recording—what mikes to use and so on. The ideal engineer for all of us was Rudy Van Gelder. The technique he used was simple but not that easy to get down in a studio. A studio isn’t live. It’s kind of dry and clear.

MM: Who specifically named the band after a sex toy?

DF: It was a spur of the moment thing in '72. We needed aname quickly. They had an album cover made up, and Walter and I were both fans of William Burroughs. We would have come up with something else but we went with it. Now, of course, we’re stuck with it. I like it, though. It’s a good name. We weren’t trying to shock or anything. In those days you didn’t think much about those things. It's not like today, where every inside joke is immediately exposed.

MM: Do you see a lot of people under age 45 at your concerts?

DF: We don’t care as long as people come [laughs]. We’re sort of free of audience influence. We want everyone to have a good time. We figure that the both of us are our ideal fans and figure that they’re going to like what we like. Who says audiences know more than we do about what’s good?

MM: Did you have music training before or after Bard College?

DF: I took some piano lessons but I trained myself by ear. I did it the way jazz musicians used to learn—by slowing down jazz records and playing along until you figured out what they were doing. At first I used to imitate Red Garland. Of course, I never achieved that level. Then I listened to Bud Powell and Bill Evans. I liked Horace Silver but not a lot. I was so snobby in high school. I didn’t like funky jazz that much. I never bought Blue Note records. I thought Alfred Lion had too much influence over the music that was being played and recorded. Now, of course, I like those albums.

MM: Do you and Walter Becker still care what each other thinks?

DF: We’ve had our moments. Between 1980 and 1985, we split up. The break wasn’t really anything personal. We just ran out of steam. A few years later we started writing again. Our relationship is based on entertaining ourselves.

MM: Which poets did you read?

DF: In high school I was heavy into W.B. Yeats. I read Richard Ellmann’s biography of Yeats. I read all of his works. I also liked William Blake. And Lawrence Ferlinghetti. I had older cousins who were jazz fans and sort of beatniks. I’d see these slim volumes of Ferlinghetti's laying around their house and I’d pick them up.

MM: How do you come up with such imaginative word combos in your lyrics?

DF: It’s mostly intuitive. I grew up in New Jersey and traveled into New York a lot. I went to public school, and the way kids used to talk got into the songs. It's demotic slang. Walter and I enjoy making up our own slang. We'd make up slang advertising slogans.

MM: For example?

DF: For example, in Josie [from Aja], a street gang uses a weapon called a "battle apple." I don't know what that is, but it sounded better than anything else we could come up with.

MM: What else did you read?

DF: Walter and I enjoyed reading science fiction as kids.Writers like Alfred Bester, Fredric Brown and Robert Heinlein. They were mainly writing satire under the guise of science fiction. They created this alternate reality that's sort of like this one. They all had a sense of humor. Frederic Brown, Theodore Sturgeon and Frederik Pohl also were great science fiction writers. Cyril Kornbluth, too. They got you to think expansively.

MM: Was Horace Silver a major influence?

DF: How do you mean?

MM: I hear Peg in Outlaw and Aja in Moon Rays. Or am I hearing things?

DF: Interesting. There was no thought of that.

MM: What about the intro to Rikki Don't Lose That Number and Silver's Song for My Father?

DF: There was never a conscious thought about picking upHorace Silver's intro. We wrote this Brazilian bass line and when drummer Jim Gordon heard it, he played his figures. As for the piano line, I think I had heard it on an old Sergio Mendes album. Maybe that's where Horace heard it, too [laughs].

MM: Do you still enjoy Woody Herman’s Chick, Donald, Walter & Woodrow from 1978?

DF: Very much. We were invited to the session back then, and it was a lot of fun meeting Woody and the guys in his band. I thought the charts of our songs were smart.

MM: Among rock musicians, you have perhaps the strongest affinity for jazz and jazz musicians. Is it the outcast thing?

DF: Being an outcast is secondary. The primary motive is the music and freedom. Walter and I started out as hardcore jazz fans. When we were growing up, there were still late-night radio shows. Walter and I were both insomniacs. We'd find these jazz shows on the radio and go into them. We were 10 or 11 years old.

MM: What were you listening to in the late '50s?

DF: I was buying Chuck Berry records at the time—or I had my mother buy them for me. Around the time rock went vanilla I discovered all these radio shows. So I gave all my rock records to my younger sister and only listened to jazz. I loved the mystique of the nighttime radio scene. You’d see these pictures of Coltrane, Monk and Miles—these dark blue photos on album covers. After a while I subscribed toDown Beat. When I was 13 or 14, my cousin started to get me into the Village Vanguard, where I saw Coleman Hawkins, Charles Mingus, Count Basie and so many others. [Owner] Max [Gordon] got to know me and let me sit near the drums and nurse a Coke.

MM: What about a Donald Fagen jazz album?

DF: I’ve always thought of my style as quirky. I always thought I could do something the way Thelonious Monk does, where he has his own eccentric way of improvising that wouldn't require great speed. But it seems the more I practice, the worse I get. I started late, and muscles and reflexes don't develop properly. Fingers four and five don't work so well.

MM: You're married to Libby Titus. What’s it like for two Type-A songwriters to be married to each other? Do you fight over the piano?

DF: [Laughs] Libby got out of music years ago to produce. She was producing some live shows in small venues when we met. She's no longer producing.

MM: I wonder why her albums are no longer in print? They're quite good.

DF: Yeah, I think so.

MM: Your upcoming tour schedule looks like a triathlon. Is touring as arduous as it looks?

DF: At this point I’m used to traveling. We travel well. We have a chartered plane for a lot of it. And nice hotels. I’m 63, so I get tired. On these tours, you tend to do a lot of sleeping. You don’t go back the hotel and cut loose.

MM: Sometimes you don’t seem comfortable on stage. Is it boredom? Stage fright?

DF: I’ve never been comfortable as a lead performer. I never wanted to be a singer particularly. But we couldn’t find anyone to be the lead singer who had the right attitude to put over the material. We tried. At one point we asked Loudon Wainwright but he was underwhelmed by the idea. The music needs that smirky feel. I just do it without thinking.

MM: From the creator’s standpoint, what makes Aja magical?

DF: That’s for the listeners to decide. We just make ‘em.

MM: But isn't there something special there?

DF: The only thing I can say is that we used a lot of session musicians then. We were hiring session musicians who we thought were right for the material. Right around that time, in the mid-‘70s, there was a style change, a paradigm shift, in the way session musicians were playing. Younger players had started to add more jazz flavored stuff in their playing. In the early days, it was hard to find a player who was familiar with r&b's backbeat and could negotiate jazz harmony with ease. And a jazz player tended to play much looser than we required. But by the mid-‘70s, there were players like Steve Gadd and Larry Carlton who could do both. They had no trouble playing jazz chords and also had a very rhythmic sense.

MM: Aja is very much a jazz album.

DF: Well, I don’t really label them. When I think of jazz, I think of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. The change in our sound had to do with the musicians we were using more than what we were doing.

MM: What haven’t you ever told anyone before about the album Aja?

DF: Wow. Well, I know that halfway through we decided we wanted to go back to NY and do some tracks with some of the people we knew in the city. We felt that although there were great musicians in L.A., we were missing a little bit of soul from the days we were doing New York sessions. Half the album was done in L.A. and half was done in New York. We brought Larry Carlton back with us to New York to supervise. Other than Larry, we used New York players. It gave the album soul. We were able to use Paul Griffin and Don Grolnick on keyboards and engineer Elliot Scheiner—guys we knew from the early days. Also drummers like Rick Marotta and Bernard Purdie.

MM: You seem to take special pleasure in singing Hey Nineteen. Why?

DF: I know the audience likes it, and also it’s maybe a little simpler than our other stuff. It’s easy to sing. I don’t have to think about it that much. By the way—getting back to something you said earlier—if I seem uncomfortable on stage, it’s because I am. Not being a trained singer—I mean, I have had some coaching over the years—In order to sing what’s not the easiest stuff to sing, because I’m basically singing a lot of horn lines and stuff like that. I have to really concentrate. You know, I’d really rather be playing in a way. But I’ve come to enjoy the singing part as well.

MM: You seem to be playing different characters up there.

DF: Everyone has a stage persona. It’s hard to escape that. I don’t really have an act. That’s just it. Sort of what you see is what you get. I sort of have to psychologically prepare myself to not give a shit—what I look like and so on. Then I just go out and do it. That’s just it. I just grew up that way. I can’t help it.

MM: In your band, is Michael Leonhart related to the jazz bass player Jay Leonhart?

DF: Yes, Michael is his son. We have two of his children in our band. Michael is the trumpet player and his sister Carolyn is one of our singers.

MM: Will the Steely Dan catalog finally be remastered with today's technology? What’s holding it up?

DF: You got me. They don’t really communicate with me. As the years go by, you kind of lose touch with that stuff. We have always been very careful with the mastering process.

MM: But you’d be open to it now?

DF: Yeah, sure.

MM: Who specifically named the band after a sex toy?

DF: It was a spur of the moment thing in '72. We needed aname quickly. They had an album cover made up, and Walter and I were both fans of William Burroughs. We would have come up with something else but we went with it. Now, of course, we’re stuck with it. I like it, though. It’s a good name. We weren’t trying to shock or anything. In those days you didn’t think much about those things. It's not like today, where every inside joke is immediately exposed.

MM: Do you see a lot of people under age 45 at your concerts?

DF: We don’t care as long as people come [laughs]. We’re sort of free of audience influence. We want everyone to have a good time. We figure that the both of us are our ideal fans and figure that they’re going to like what we like. Who says audiences know more than we do about what’s good?

MM: Did you have music training before or after Bard College?

DF: I took some piano lessons but I trained myself by ear. I did it the way jazz musicians used to learn—by slowing down jazz records and playing along until you figured out what they were doing. At first I used to imitate Red Garland. Of course, I never achieved that level. Then I listened to Bud Powell and Bill Evans. I liked Horace Silver but not a lot. I was so snobby in high school. I didn’t like funky jazz that much. I never bought Blue Note records. I thought Alfred Lion had too much influence over the music that was being played and recorded. Now, of course, I like those albums.

MM: Do you and Walter Becker still care what each other thinks?

DF: We’ve had our moments. Between 1980 and 1985, we split up. The break wasn’t really anything personal. We just ran out of steam. A few years later we started writing again. Our relationship is based on entertaining ourselves.

MM: Which poets did you read?

DF: In high school I was heavy into W.B. Yeats. I read Richard Ellmann’s biography of Yeats. I read all of his works. I also liked William Blake. And Lawrence Ferlinghetti. I had older cousins who were jazz fans and sort of beatniks. I’d see these slim volumes of Ferlinghetti's laying around their house and I’d pick them up.

MM: How do you come up with such imaginative word combos in your lyrics?

DF: It’s mostly intuitive. I grew up in New Jersey and traveled into New York a lot. I went to public school, and the way kids used to talk got into the songs. It's demotic slang. Walter and I enjoy making up our own slang. We'd make up slang advertising slogans.

MM: For example?

DF: For example, in Josie [from Aja], a street gang uses a weapon called a "battle apple." I don't know what that is, but it sounded better than anything else we could come up with.

MM: What else did you read?

DF: Walter and I enjoyed reading science fiction as kids.Writers like Alfred Bester, Fredric Brown and Robert Heinlein. They were mainly writing satire under the guise of science fiction. They created this alternate reality that's sort of like this one. They all had a sense of humor. Frederic Brown, Theodore Sturgeon and Frederik Pohl also were great science fiction writers. Cyril Kornbluth, too. They got you to think expansively.

MM: Was Horace Silver a major influence?

DF: How do you mean?

MM: I hear Peg in Outlaw and Aja in Moon Rays. Or am I hearing things?

DF: Interesting. There was no thought of that.

MM: What about the intro to Rikki Don't Lose That Number and Silver's Song for My Father?

DF: There was never a conscious thought about picking upHorace Silver's intro. We wrote this Brazilian bass line and when drummer Jim Gordon heard it, he played his figures. As for the piano line, I think I had heard it on an old Sergio Mendes album. Maybe that's where Horace heard it, too [laughs].

MM: Do you still enjoy Woody Herman’s Chick, Donald, Walter & Woodrow from 1978?

DF: Very much. We were invited to the session back then, and it was a lot of fun meeting Woody and the guys in his band. I thought the charts of our songs were smart.

MM: Among rock musicians, you have perhaps the strongest affinity for jazz and jazz musicians. Is it the outcast thing?

DF: Being an outcast is secondary. The primary motive is the music and freedom. Walter and I started out as hardcore jazz fans. When we were growing up, there were still late-night radio shows. Walter and I were both insomniacs. We'd find these jazz shows on the radio and go into them. We were 10 or 11 years old.

MM: What were you listening to in the late '50s?

DF: I was buying Chuck Berry records at the time—or I had my mother buy them for me. Around the time rock went vanilla I discovered all these radio shows. So I gave all my rock records to my younger sister and only listened to jazz. I loved the mystique of the nighttime radio scene. You’d see these pictures of Coltrane, Monk and Miles—these dark blue photos on album covers. After a while I subscribed toDown Beat. When I was 13 or 14, my cousin started to get me into the Village Vanguard, where I saw Coleman Hawkins, Charles Mingus, Count Basie and so many others. [Owner] Max [Gordon] got to know me and let me sit near the drums and nurse a Coke.

MM: What about a Donald Fagen jazz album?

DF: I’ve always thought of my style as quirky. I always thought I could do something the way Thelonious Monk does, where he has his own eccentric way of improvising that wouldn't require great speed. But it seems the more I practice, the worse I get. I started late, and muscles and reflexes don't develop properly. Fingers four and five don't work so well.

MM: You're married to Libby Titus. What’s it like for two Type-A songwriters to be married to each other? Do you fight over the piano?

DF: [Laughs] Libby got out of music years ago to produce. She was producing some live shows in small venues when we met. She's no longer producing.

MM: I wonder why her albums are no longer in print? They're quite good.

DF: Yeah, I think so.

MM: Your upcoming tour schedule looks like a triathlon. Is touring as arduous as it looks?

DF: At this point I’m used to traveling. We travel well. We have a chartered plane for a lot of it. And nice hotels. I’m 63, so I get tired. On these tours, you tend to do a lot of sleeping. You don’t go back the hotel and cut loose.

MM: Sometimes you don’t seem comfortable on stage. Is it boredom? Stage fright?

DF: I’ve never been comfortable as a lead performer. I never wanted to be a singer particularly. But we couldn’t find anyone to be the lead singer who had the right attitude to put over the material. We tried. At one point we asked Loudon Wainwright but he was underwhelmed by the idea. The music needs that smirky feel. I just do it without thinking.

MM: From the creator’s standpoint, what makes Aja magical?

DF: That’s for the listeners to decide. We just make ‘em.

MM: But isn't there something special there?

DF: The only thing I can say is that we used a lot of session musicians then. We were hiring session musicians who we thought were right for the material. Right around that time, in the mid-‘70s, there was a style change, a paradigm shift, in the way session musicians were playing. Younger players had started to add more jazz flavored stuff in their playing. In the early days, it was hard to find a player who was familiar with r&b's backbeat and could negotiate jazz harmony with ease. And a jazz player tended to play much looser than we required. But by the mid-‘70s, there were players like Steve Gadd and Larry Carlton who could do both. They had no trouble playing jazz chords and also had a very rhythmic sense.

MM: Aja is very much a jazz album.

DF: Well, I don’t really label them. When I think of jazz, I think of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. The change in our sound had to do with the musicians we were using more than what we were doing.

MM: What haven’t you ever told anyone before about the album Aja?

DF: Wow. Well, I know that halfway through we decided we wanted to go back to NY and do some tracks with some of the people we knew in the city. We felt that although there were great musicians in L.A., we were missing a little bit of soul from the days we were doing New York sessions. Half the album was done in L.A. and half was done in New York. We brought Larry Carlton back with us to New York to supervise. Other than Larry, we used New York players. It gave the album soul. We were able to use Paul Griffin and Don Grolnick on keyboards and engineer Elliot Scheiner—guys we knew from the early days. Also drummers like Rick Marotta and Bernard Purdie.

MM: You seem to take special pleasure in singing Hey Nineteen. Why?

DF: I know the audience likes it, and also it’s maybe a little simpler than our other stuff. It’s easy to sing. I don’t have to think about it that much. By the way—getting back to something you said earlier—if I seem uncomfortable on stage, it’s because I am. Not being a trained singer—I mean, I have had some coaching over the years—In order to sing what’s not the easiest stuff to sing, because I’m basically singing a lot of horn lines and stuff like that. I have to really concentrate. You know, I’d really rather be playing in a way. But I’ve come to enjoy the singing part as well.

MM: You seem to be playing different characters up there.

DF: Everyone has a stage persona. It’s hard to escape that. I don’t really have an act. That’s just it. Sort of what you see is what you get. I sort of have to psychologically prepare myself to not give a shit—what I look like and so on. Then I just go out and do it. That’s just it. I just grew up that way. I can’t help it.

MM: In your band, is Michael Leonhart related to the jazz bass player Jay Leonhart?

DF: Yes, Michael is his son. We have two of his children in our band. Michael is the trumpet player and his sister Carolyn is one of our singers.

MM: Will the Steely Dan catalog finally be remastered with today's technology? What’s holding it up?

DF: You got me. They don’t really communicate with me. As the years go by, you kind of lose touch with that stuff. We have always been very careful with the mastering process.

MM: But you’d be open to it now?

DF: Yeah, sure.

From the excellent JazzWax site: http://www.jazzwax.com/2011/07/interview-donald-fagen.html

Monday, 28 November 2016

Sunday, 27 November 2016

Saturday, 26 November 2016

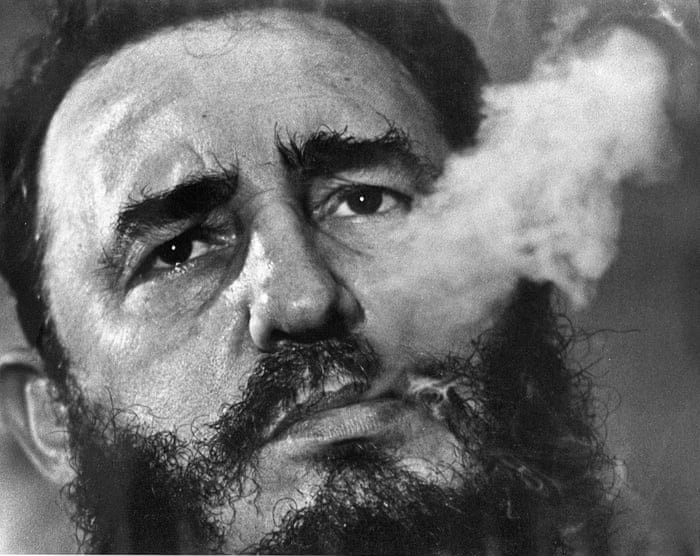

Fidel Castro RIP

Cuba’s revolutionary leader, Fidel Castro, dies aged 90

The comandante overthrew Batista, established a communist state and survived countless American assassination attemptsRory Carroll

The Guardian

Saturday 26 November 2016

Fidel Castro has died at the age of 90, bringing an end to an era for the country, Latin America and world.

The revolutionary icon, one of the world’s best-known and most controversial leaders, survived countless US assassination attempts and premature obituaries, but in the end proved mortal and died late on Friday night after a long battle with illness.

Given the former president’s age and health problems, the announcement of Castro’s death had long been expected. But when it came it was still a shock: thecomandante – a figurehead for armed struggle across the developing world – was no more. It was news that friends and foes had long dreaded and yearned for respectively.

Castro’s younger brother Raúl, who assumed the presidency of Cuba in 2006 after Fidel suffered a near-fatal intestinal ailment, announced the revolutionary leader’s death on television on Friday night.

“With profound sadness I am appearing to inform our people and our friends across [Latin] America and the world that today, 25 November 2016, at 10.29pm, Fidel Castro, the commander in chief of the Cuban revolution, died,” he said.

“In accordance with his wishes, his remains will be cremated.”

Raúl Castro said that further details of the posthumous tribute would be released on Saturday, concluding his address with the famous revolutionary slogan: “Onwards to victory!”

Castro survived long enough to see Raúl negotiate an opening with the outgoing US president, Barack Obama, in December 2014, when Washington and Havana announced they would move to restore diplomatic ties for the first time since they were severed in 1961.

After outlasting nine occupants of the White House, he cautiously blessed the historic deal with his lifelong enemy in a letter published after a month-long silence.

The thaw in relations was crowned when Obama visited the island earlier this year. Castro did not meet Obama and days later wrote a scathing column condemning the US president’s “honey-coated” words and reminding Cubans of the many US attempts to overthrow and weaken the communist government.

As in life, in death Castro was deeply divisive. The announcement of his death was widely greeted online with celebration and condemnation of a “cruel dictator” and his repressive regime.

Others mourned the passing of “a fighter of US imperialism” and a “charismatic icon”.

In Miami, home to the largest diaspora of expatriate Cubans, people took to the streets celebrating his death, singing, dancing, and waving Cuban flags. As pots and pans were banged in jubilation, there were chants of “Cuba Libre!” (Cuba is Free) and “el viejo murió” (the old man is dead). Previous false reports of Castro’s death have triggered cavalcades of cheering, flag-waving revellers.

Cuba’s Communist party and state apparatus has prepared for this moment since July 2006 when Castro underwent emergency intestinal surgery and ceded power to his brother, Raúl, who remains in charge.

Fidel wrote occasional columns for the party paper, Granma, and made very occasional public appearances – most recently at the 2016 Communist party congress – but otherwise kept a very low profile.

Despite the mixed reactions to his death, one thing all could agree on was that this extraordinary figure had left his mark on history.

More than half a century ago, his guerrilla army of “bearded ones” replaced Fulgencio Batista’s corrupt dictatorship with communist rule which challenged the US and turned the island into a cold-war crucible.

He fended off a CIA-backed invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 as well as many assassination attempts. His alliance with Moscow helped trigger the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, a 13-day showdown with the US that brought the world closer to the brink of nuclear war than it has ever been.

The US had long counted on Castro’s mortality as a “biological solution” to communism in the Caribbean but, since officially succeeding his brother in 2008, Raúl has cemented his own authority while overseeing cautious economic reforms, and agreeing the momentous deal to restore diplomatic relations between Cuba and the US in late 2014.

By Raúl’s own admission, however, Fidel is irreplaceable. By force of charisma, intellect and political cunning the lawyer-turned-guerrilla embodied the revolution. Long before his passing, however, Cubans had started to move on, with increased migration to the US and an explosion of small private businesses.

His greatest legacy is free healthcare and education, which have given Cuba some of the region’s best human development statistics. But he is also responsible for the central planning blunders and stifling government controls that – along with the US embargo – have strangled the economy, leaving most Cubans scrabbling for decent food and desperate for better living standards.

The man who famously declared “history will absolve me” leaves a divided legacy. Older Cubans who remember brutal times under Batista tend to emphasise the revolution’s accomplishments. Younger Cubans are more likely to rail against gerontocracy, repression and lost opportunity. But even they refer to Castro by the more intimate name of Fidel.

Since largely vanishing from public view he has been a spectral presence, occasionally surfacing in what became a trademark tracksuit, to urge faith in the revolution. It was a long goodbye that accustomed Cubans to his mortality.

Latin America’s leftist leaders will mourn the passing of a figure who was perceived less as a communist and more as a nationalist symbol of regional pride and defiance against the “gringo” superpower.

Fidel Castro’s funeral and cremation are expected to attract numerous foreign heads of state, intellectuals and artists.

Saturday 26 November 2016

Fidel Castro has died at the age of 90, bringing an end to an era for the country, Latin America and world.

The revolutionary icon, one of the world’s best-known and most controversial leaders, survived countless US assassination attempts and premature obituaries, but in the end proved mortal and died late on Friday night after a long battle with illness.

Given the former president’s age and health problems, the announcement of Castro’s death had long been expected. But when it came it was still a shock: thecomandante – a figurehead for armed struggle across the developing world – was no more. It was news that friends and foes had long dreaded and yearned for respectively.

Castro’s younger brother Raúl, who assumed the presidency of Cuba in 2006 after Fidel suffered a near-fatal intestinal ailment, announced the revolutionary leader’s death on television on Friday night.

“With profound sadness I am appearing to inform our people and our friends across [Latin] America and the world that today, 25 November 2016, at 10.29pm, Fidel Castro, the commander in chief of the Cuban revolution, died,” he said.

“In accordance with his wishes, his remains will be cremated.”

Raúl Castro said that further details of the posthumous tribute would be released on Saturday, concluding his address with the famous revolutionary slogan: “Onwards to victory!”

Castro survived long enough to see Raúl negotiate an opening with the outgoing US president, Barack Obama, in December 2014, when Washington and Havana announced they would move to restore diplomatic ties for the first time since they were severed in 1961.

After outlasting nine occupants of the White House, he cautiously blessed the historic deal with his lifelong enemy in a letter published after a month-long silence.

The thaw in relations was crowned when Obama visited the island earlier this year. Castro did not meet Obama and days later wrote a scathing column condemning the US president’s “honey-coated” words and reminding Cubans of the many US attempts to overthrow and weaken the communist government.

As in life, in death Castro was deeply divisive. The announcement of his death was widely greeted online with celebration and condemnation of a “cruel dictator” and his repressive regime.

Others mourned the passing of “a fighter of US imperialism” and a “charismatic icon”.

In Miami, home to the largest diaspora of expatriate Cubans, people took to the streets celebrating his death, singing, dancing, and waving Cuban flags. As pots and pans were banged in jubilation, there were chants of “Cuba Libre!” (Cuba is Free) and “el viejo murió” (the old man is dead). Previous false reports of Castro’s death have triggered cavalcades of cheering, flag-waving revellers.

Cuba’s Communist party and state apparatus has prepared for this moment since July 2006 when Castro underwent emergency intestinal surgery and ceded power to his brother, Raúl, who remains in charge.

Fidel wrote occasional columns for the party paper, Granma, and made very occasional public appearances – most recently at the 2016 Communist party congress – but otherwise kept a very low profile.

Despite the mixed reactions to his death, one thing all could agree on was that this extraordinary figure had left his mark on history.

More than half a century ago, his guerrilla army of “bearded ones” replaced Fulgencio Batista’s corrupt dictatorship with communist rule which challenged the US and turned the island into a cold-war crucible.

He fended off a CIA-backed invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 as well as many assassination attempts. His alliance with Moscow helped trigger the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, a 13-day showdown with the US that brought the world closer to the brink of nuclear war than it has ever been.

The US had long counted on Castro’s mortality as a “biological solution” to communism in the Caribbean but, since officially succeeding his brother in 2008, Raúl has cemented his own authority while overseeing cautious economic reforms, and agreeing the momentous deal to restore diplomatic relations between Cuba and the US in late 2014.

By Raúl’s own admission, however, Fidel is irreplaceable. By force of charisma, intellect and political cunning the lawyer-turned-guerrilla embodied the revolution. Long before his passing, however, Cubans had started to move on, with increased migration to the US and an explosion of small private businesses.

His greatest legacy is free healthcare and education, which have given Cuba some of the region’s best human development statistics. But he is also responsible for the central planning blunders and stifling government controls that – along with the US embargo – have strangled the economy, leaving most Cubans scrabbling for decent food and desperate for better living standards.

The man who famously declared “history will absolve me” leaves a divided legacy. Older Cubans who remember brutal times under Batista tend to emphasise the revolution’s accomplishments. Younger Cubans are more likely to rail against gerontocracy, repression and lost opportunity. But even they refer to Castro by the more intimate name of Fidel.

Since largely vanishing from public view he has been a spectral presence, occasionally surfacing in what became a trademark tracksuit, to urge faith in the revolution. It was a long goodbye that accustomed Cubans to his mortality.

Latin America’s leftist leaders will mourn the passing of a figure who was perceived less as a communist and more as a nationalist symbol of regional pride and defiance against the “gringo” superpower.

Fidel Castro’s funeral and cremation are expected to attract numerous foreign heads of state, intellectuals and artists.

Friday, 25 November 2016

Dead Poets Society #17 Siegfried Sassoon: Suicide in the Trenches

Suicide in the Trenches by Siegfried Sassoon

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled early with the lark.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you'll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

Thursday, 24 November 2016

Last night's set lists

Ron Elderly: -

My Home Town

The Way You Look Tonight

I'll See You In My Dreams

Autumn Leaves

Da Elderly: -

Love Song

In The Morning Light

Mellow My Mind

There Stands The Glass

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Price Of Love

Country Roads

You Got It

Yes I Will

Just when you think you've seen it all - only at The Habit open mic night would someone bring a piano!! Said piano just made it through the door, something it had failed to do across the road at the Snickleway Inn - note to performers...always check the width of the doorway before wheeling your piano all the way to the gig!!

All told it was a rather quiet night performer-wise with some folks getting a second chance to play - and there was room for 4 songs each this week. There was a strong showing for the songs of Elton John, David Bowie and Ray LaMontagne. After the open mic finished, The Elderly Brothers kept the audience entertained with unplugged requests including songs by Elvis, Neil Young and The Beatles. Another fun-packed night.

My Home Town

The Way You Look Tonight

I'll See You In My Dreams

Autumn Leaves

Da Elderly: -

Love Song

In The Morning Light

Mellow My Mind

There Stands The Glass

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Price Of Love

Country Roads

You Got It

Yes I Will

Just when you think you've seen it all - only at The Habit open mic night would someone bring a piano!! Said piano just made it through the door, something it had failed to do across the road at the Snickleway Inn - note to performers...always check the width of the doorway before wheeling your piano all the way to the gig!!

All told it was a rather quiet night performer-wise with some folks getting a second chance to play - and there was room for 4 songs each this week. There was a strong showing for the songs of Elton John, David Bowie and Ray LaMontagne. After the open mic finished, The Elderly Brothers kept the audience entertained with unplugged requests including songs by Elvis, Neil Young and The Beatles. Another fun-packed night.

Wednesday, 23 November 2016

Geoff Hattersley - The Only Son at the Fish 'n' Chip Shop

He lived with his mother till he was forty-five

and no one was allowed to touch his head.

He worked on a novel for twenty years

without writing a word. He didn’t like people

who wrote novels. He often drank. One glass of beer

was too many, two glasses weren’t enough.

Travel brochures were as far as he went.

A football match, one time. He often said

Why would anyone want to think about a potato?

He painted his door with nobody’s help.

GEOFF HATTERSLEY

From Back of Beyond: New and Selected Poems (Smith/Doorstop Books, 2006)

Tuesday, 22 November 2016

David Tindle Retrospective at Huddersfield Art Gallery

David Tindle RA: A Retrospective review – lush yet spectral

Huddersfield Art Gallery

One of the finest figurative painters of his generation, David Tindle remains unknown to many. This retrospective is long overdue

Rachel Cooke

Tindle, who now lives and works in Italy, wasn’t always unknown, of course. In a vitrine at Huddersfield Art Gallery you can see the newspaper reports that greeted his arrival on the scene in the early 50s: an angular, floppy-haired fellow who, by the critics’ account, was coming up hard on the heels of Prunella Clough, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Keith Vaughan. After a six-month stint at junior art college in Coventry and two years’ graft at a commercial art studio, Tindle had his first London exhibition aged just 19, having moved to the city to work with the theatrical scene-painter Edward Delaney (the business of painting backdrops, “working in a big flow of colour”, was to have a profound and lasting influence on his work). The exhibition changed everything. An admirer of John Minton, Tindle found the artist’s number in the telephone book and rang to invite him to see it. Minton did, and the two became friends. Also in the vitrine is Tindle’s 1952 pencil drawing of Minton, tender and reverent.

Mother and Child, 1954

Mother and Child, 1954

Through Minton, Tindle met Freud, Vaughan and the rest – older men who helped build his sense of himself as an artist. He was then “very susceptible to influence”, and you see this in the early works: Barges on the Regent’s Canal(1954, ink and watercolour on paper) shows what he learned about line from Minton; Freud exerts a clear hold on the wondrously detailed Mother and Child(1954, oil on board), a portrait of Tindle’s baby son, John, on the breast. The more abstract Paddington (1961, oil and sand on canvas) links to Frank Auerbach’s work of the same period. But already Tindle’s paintings have an extraordinary presence: there is something sacramental about the arrangement of the objects in his still lifes. Broken Egg Shell (1954, oil on board) is an extraordinary picture. At first sight it belongs to the school of William Nicholson, a study in beauty, light and shadow. But look closer and the eggshell in question seems to be out of proportion, almost planet-like on its white plate, which is itself balanced on a moonscape rather than a tablecloth. Here is the first whisper of the atmosphere that will pervade Tindle’s mature work, which plays in the most delicate way with the idea of realism.

Broken Egg Shell, 1954

Broken Egg Shell, 1954

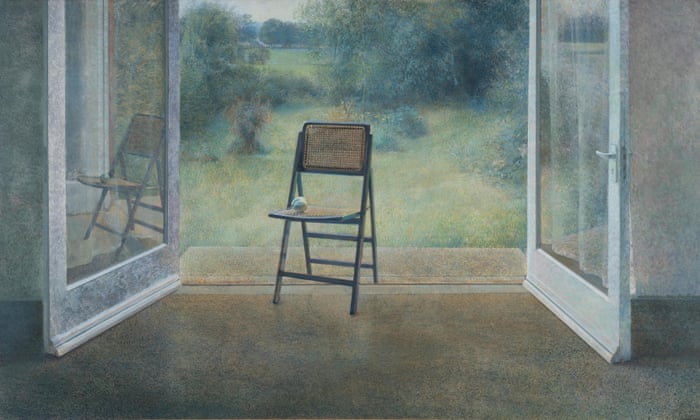

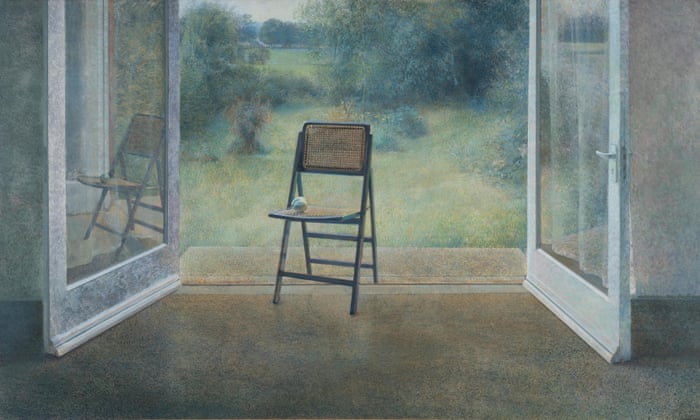

The sea change came in the early 1970s, when he swapped oil and acrylic for egg tempera, an exacting medium that helped him achieve a “crisper articulation of form”, a quality closer to a photograph. The result was, and is, stunning. He used it for still lifes and portraits (Tindle is a gorgeous, empathetic portraitist, and several are included in this show, including a study for a painting of Dirk Bogarde commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery), but its most perfect expression can be seen in the series of gardens – verdant rooms, really – that he painted through the 70s and well into the 80s: Garden, Evening (1979); Garden on the Hill, 7am (1984); Egg on a Table (1985). These have recurring motifs: doors and windows to form pictures within pictures, a theatrical framing device that may be traced back to his scenery painting days; a carefully placed chair, often featuring some kind of basketwork, and on it, perhaps, an apple. However, it’s their atmosphere, lush yet spectral, that hangs in the mind like mist.

Egg on a Table, 1985

Tindle has said that in these works “memory and presence are very close”. They are, in other words, depictions of real places, recollected in the tranquillity of the studio. I can’t really describe the powerful effect they have on me. Only the work of Michael Andrews, his near contemporary and with whom his work shares a certain tone, moves me more. The finest of them all, Garden on the Edge of the Village (1976), depicts those few moments on a cold but bright winter’s day just before dusk. We are in an allotment or cultivated field close to a farmhouse, where a small bonfire still smokes; the sky is mottled, like an old enamel mug. It is a painting that is at once both calm and urgent, an eternal scene but also a vanishing one. Tindle, you finally realise, is as interested in time as he is in place. How to capture it? Light is the key. It illuminates his work, warms it seemingly from within, humanising his extraordinary skill. But it is also a metaphor. Beyond the trees, the wall, the hedge, darkness is creeping ever closer.

David Tindle RA: A Retrospective is at Huddersfield Art Gallery until 4 February 2017

Huddersfield Art Gallery

One of the finest figurative painters of his generation, David Tindle remains unknown to many. This retrospective is long overdue

Rachel Cooke

The Guardian

Sunday 20 November 2016

Unless you live there, or close by, Huddersfield isn’t particularly easy to reach. The journey by train from Wakefield can take up to 40 minutes, the puttering two-carriage engine that works this route no match at all for the town’s magnificent neoclassical station. But never mind. Who cares about bad connections and too-weak Costa tea when at the end is one of the loveliest small exhibitions you’re likely to see this side of Brexit, and perhaps far beyond it?

Sunday 20 November 2016

Unless you live there, or close by, Huddersfield isn’t particularly easy to reach. The journey by train from Wakefield can take up to 40 minutes, the puttering two-carriage engine that works this route no match at all for the town’s magnificent neoclassical station. But never mind. Who cares about bad connections and too-weak Costa tea when at the end is one of the loveliest small exhibitions you’re likely to see this side of Brexit, and perhaps far beyond it?

Garden on the Edge of the Village, 1976

The painter David Tindle was born in Huddersfield in 1932, and though he grew up largely in Coventry, it’s this connection that has given the town’s art gallery an excuse to stage a long overdue retrospective of a career that began in the late 40s and continues still. Will this ignite new interest in him, an artist whose name is now far too little known? I hope so, and the show may yet (fingers crossed) travel. In the meantime, seek it out and you will discover, over the course of just two oblong rooms, an uncommonly exquisite painter whose sensibility, imbuing as it does the quotidian with the numinous, can be traced back to Samuel Palmer and forward to another Coventry man, George Shaw.

Baltais Dzidrais, 1979

The painter David Tindle was born in Huddersfield in 1932, and though he grew up largely in Coventry, it’s this connection that has given the town’s art gallery an excuse to stage a long overdue retrospective of a career that began in the late 40s and continues still. Will this ignite new interest in him, an artist whose name is now far too little known? I hope so, and the show may yet (fingers crossed) travel. In the meantime, seek it out and you will discover, over the course of just two oblong rooms, an uncommonly exquisite painter whose sensibility, imbuing as it does the quotidian with the numinous, can be traced back to Samuel Palmer and forward to another Coventry man, George Shaw.

Baltais Dzidrais, 1979

Tindle, who now lives and works in Italy, wasn’t always unknown, of course. In a vitrine at Huddersfield Art Gallery you can see the newspaper reports that greeted his arrival on the scene in the early 50s: an angular, floppy-haired fellow who, by the critics’ account, was coming up hard on the heels of Prunella Clough, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Keith Vaughan. After a six-month stint at junior art college in Coventry and two years’ graft at a commercial art studio, Tindle had his first London exhibition aged just 19, having moved to the city to work with the theatrical scene-painter Edward Delaney (the business of painting backdrops, “working in a big flow of colour”, was to have a profound and lasting influence on his work). The exhibition changed everything. An admirer of John Minton, Tindle found the artist’s number in the telephone book and rang to invite him to see it. Minton did, and the two became friends. Also in the vitrine is Tindle’s 1952 pencil drawing of Minton, tender and reverent.

Through Minton, Tindle met Freud, Vaughan and the rest – older men who helped build his sense of himself as an artist. He was then “very susceptible to influence”, and you see this in the early works: Barges on the Regent’s Canal(1954, ink and watercolour on paper) shows what he learned about line from Minton; Freud exerts a clear hold on the wondrously detailed Mother and Child(1954, oil on board), a portrait of Tindle’s baby son, John, on the breast. The more abstract Paddington (1961, oil and sand on canvas) links to Frank Auerbach’s work of the same period. But already Tindle’s paintings have an extraordinary presence: there is something sacramental about the arrangement of the objects in his still lifes. Broken Egg Shell (1954, oil on board) is an extraordinary picture. At first sight it belongs to the school of William Nicholson, a study in beauty, light and shadow. But look closer and the eggshell in question seems to be out of proportion, almost planet-like on its white plate, which is itself balanced on a moonscape rather than a tablecloth. Here is the first whisper of the atmosphere that will pervade Tindle’s mature work, which plays in the most delicate way with the idea of realism.

The sea change came in the early 1970s, when he swapped oil and acrylic for egg tempera, an exacting medium that helped him achieve a “crisper articulation of form”, a quality closer to a photograph. The result was, and is, stunning. He used it for still lifes and portraits (Tindle is a gorgeous, empathetic portraitist, and several are included in this show, including a study for a painting of Dirk Bogarde commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery), but its most perfect expression can be seen in the series of gardens – verdant rooms, really – that he painted through the 70s and well into the 80s: Garden, Evening (1979); Garden on the Hill, 7am (1984); Egg on a Table (1985). These have recurring motifs: doors and windows to form pictures within pictures, a theatrical framing device that may be traced back to his scenery painting days; a carefully placed chair, often featuring some kind of basketwork, and on it, perhaps, an apple. However, it’s their atmosphere, lush yet spectral, that hangs in the mind like mist.

Egg on a Table, 1985

Tindle has said that in these works “memory and presence are very close”. They are, in other words, depictions of real places, recollected in the tranquillity of the studio. I can’t really describe the powerful effect they have on me. Only the work of Michael Andrews, his near contemporary and with whom his work shares a certain tone, moves me more. The finest of them all, Garden on the Edge of the Village (1976), depicts those few moments on a cold but bright winter’s day just before dusk. We are in an allotment or cultivated field close to a farmhouse, where a small bonfire still smokes; the sky is mottled, like an old enamel mug. It is a painting that is at once both calm and urgent, an eternal scene but also a vanishing one. Tindle, you finally realise, is as interested in time as he is in place. How to capture it? Light is the key. It illuminates his work, warms it seemingly from within, humanising his extraordinary skill. But it is also a metaphor. Beyond the trees, the wall, the hedge, darkness is creeping ever closer.

David Tindle RA: A Retrospective is at Huddersfield Art Gallery until 4 February 2017

Monday, 21 November 2016

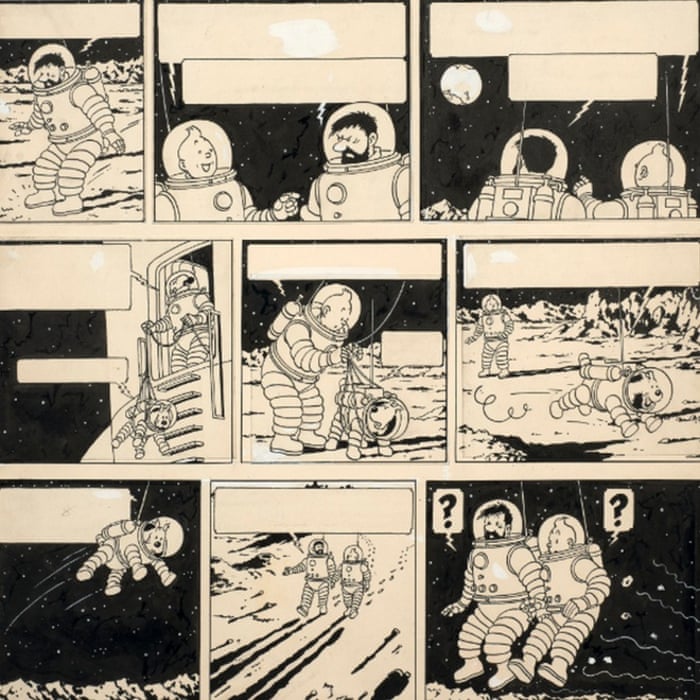

Tintin exploring the moon - a bargain at €1.55m...

Tintin drawing sells for record €1.55m in Paris auction

Original artwork by Hergé from Explorers on the Moon was expected to sell for between €700,000 and €900,000

Agence France-Presse in Paris

The Guardian

Saturday 19 November 2016

An original drawing from the popular Tintin adventure Explorers on the Moon has sold for a record €1.55m (£1.3m) in Paris, auction house Artcurial has announced.

The 50cm x 35cm drawing in Chinese ink by the Belgian cartoonist known as Hergé shows the boy reporter, his dog, Snowy, and sailor Captain Haddock wearing spacesuits and walking on the moon while looking at Earth. It had been expected to sell for between €700,000 and €900,000.

“It’s simply fantastic. It’s an exceptional price for an exceptional piece,” said Artcurial’s comics expert, Eric Leroy. He described Explorers on the Moon as “a key moment in the history of comic book art ... it has become legendary for many lovers and collectors of comic strips”.

Leroy added: “It is one of the most important from Hergé’s postwar period, on the same level as Tintin in Tibet and The Castafiore Emerald.” The 1954 book is viewed as one of Hergé’s masterpieces.

Saturday’s sale was a record for a single cartoon drawing. In 2012, the 1932 cover illustration of Tintin in America fetched €1.3m.

Hergé already holds the world record for the sale of a comic strip. A double-page ink drawing that served as the inside cover for all the Tintin adventures published between 1937 and 1958, sold for €2.65m to an American fan two years ago.

Original Tintin comic book drawings have been fetching millions at auctions in recent years. In February 2015, the original cover design for The Shooting Star almost matched the record when it was sold for €2.5m.

In May the original artwork for the last two pages of the King Ottokar’s Sceptre book sold for $1.2m (£1m), while in October 2015, a double-page slate from the same Tintin book fetched more than €1.5m. That same month, an Asian investor paid $1.2m for a drawing from The Blue Lotus book, published in 1936, of Tintin and Snowy in Shanghai.

Alongside the moon drawings, Artcurial also sold 20 ink sketches Hergé created for a series of new year greeting cards known as his “snow cards”. The drawings, including Tintin and Snowy skiing, or hapless detectives the Thompson twins ice-skating, brought in €1.2m.

Prices for cartoon art have multiplied tenfold in the last decade, according to gallery owner Daniel Maghen.

The 1954 Explorers on the Moon completes the lunar adventure started in Destination Moon (1953).

The sales come as Tintin-mania again grips Paris, with Hergé the subject of a huge retrospective exhibition at the Grand Palais.

Hergé sold about 230m Tintin books by the time of his death in 1983.

Sunday, 20 November 2016

Saturday, 19 November 2016

Mose Allison RIP

Mose Allison: farewell to a satirical blues and jazz master

From grooving with Stan Getz to piano-thumping in London’s Soho, Allison never lost his caustic charm or the earthiness of his southern rootsJohn Fordham

The Guardian

Wednesday 16 November 2016

When I was 16, I was torn between trying to learn to play guitar like the Shadows’ Hank Marvin or the Indianapolis bebop marvel Wes Montgomery. Me and my mate Dave used to stumble through Montgomery tunes on a couple of battered semi-acoustics, and after half an hour or so of it, in which we even bored ourselves, we’d play jazz LPs instead – Montgomery’s hip-looking albums for the Riverside label, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue or Porgy and Bess or Sketches of Spain, with a good many of Gil Evans’ beautiful orchestral nuances excised by the shortcomings of the Dansette record player. Everybody we listened to was purely an instrumentalist – except for Mose Allison.

I thought Dave had let the side down at first by buying a record with singing on it, but Mose did things I didn’t know singers did. His lyrics were poetic, intelligent, satirical, and mostly they didn’t seem to be about love. His quirky piano-playing was jazzy but it was oddly inflected, as if he’d learned it like a second language. He seemed to understand bebop (I heard, with fascination, that he’d been a sideman for cool-jazz saxophone star Stan Getz), but he was deeply rooted in the earthiness of the blues. He was a white kid at home and accepted in an African-American musical world, just like we wanted to be. He could write wonderful ironic poetry, as well as the kind of blistering putdown you vainly dreamed of being able come out with in the presence of a smartass.

Wednesday 16 November 2016

When I was 16, I was torn between trying to learn to play guitar like the Shadows’ Hank Marvin or the Indianapolis bebop marvel Wes Montgomery. Me and my mate Dave used to stumble through Montgomery tunes on a couple of battered semi-acoustics, and after half an hour or so of it, in which we even bored ourselves, we’d play jazz LPs instead – Montgomery’s hip-looking albums for the Riverside label, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue or Porgy and Bess or Sketches of Spain, with a good many of Gil Evans’ beautiful orchestral nuances excised by the shortcomings of the Dansette record player. Everybody we listened to was purely an instrumentalist – except for Mose Allison.

I thought Dave had let the side down at first by buying a record with singing on it, but Mose did things I didn’t know singers did. His lyrics were poetic, intelligent, satirical, and mostly they didn’t seem to be about love. His quirky piano-playing was jazzy but it was oddly inflected, as if he’d learned it like a second language. He seemed to understand bebop (I heard, with fascination, that he’d been a sideman for cool-jazz saxophone star Stan Getz), but he was deeply rooted in the earthiness of the blues. He was a white kid at home and accepted in an African-American musical world, just like we wanted to be. He could write wonderful ironic poetry, as well as the kind of blistering putdown you vainly dreamed of being able come out with in the presence of a smartass.

More than three decades later in the 1990s, when I started regularly hearing him play live on what became his twice-yearly trips to the Pizza Express Jazz Club in Soho, London, it was wonderful to hear how much of the old bite and unsentimental realism remained, that he was still producing new material, and that his resourcefulness as a piano improviser had, if anything, expanded. In his lean, wise, grey-bearded 70s, he would arrive on stage as if passing through to a more urgent appointment somewhere else, throw his jacket on the piano lid and barrel through classic songs at headlong speed, draining them and moving on as if he were leaving empties on a bar. He didn’t talk much or tell anecdotes about what must have been a fascinating life, preferring to thumbnail-sketch the biographies and credit the importance of the southern country and blues artists, famous or unknown, whose work he would often cover. And he would play a great deal of piano, mixing insistent, boogying grooves with unexpectedly ornate flourishes and fills, without ever letting an underlying and hard-hit chordal punctuation stay quiet for long.

Timeless Allison lyrics – “Ever since the world ended, I don’t get out so much”, “Your mind’s on vacation but your mouth’s working overtime” and “Y’know if silence was golden, you couldn’t raise a dime” – never lost their caustic charm, and as the ages of many of his fans advanced along with him, it was also gratifying to witness him turning his scalpel on what life as a senior citizen could feel like. “The young man is the man of the hour, 35 years of purchasing power,” the octogenarian Allison would snap, over a rocking piano vamp and glittering boppish rejoinders that sounded as if he was still 35 himself – winding up Old Man Blues with the indictment: “An old man ain’t nothin’ in the USA.” In this new political era, we’ll miss him even more.

Friday, 18 November 2016

Dead Poets Society #16 Stevie Smith: Alone in the Woods

Alone in the Woods by Stevie Smith

The bitter hostility of the sky and the trees

Nature has taught her creatures to hate

Man that fusses and fumes

Unquiet man

As the sap rises in the trees

As the sap paints the trees a violent green

So rises the wrath of Nature's creatures

At man

So paints the face of Nature a violent green.

Nature is sick at man

Sick at his fuss and fume

Sick at his agonies

Sick at his gaudy mind

That drives his body

Ever more quickly

More and more

In the wrong direction.

Thursday, 17 November 2016

Last night's set lists

At The Habit, York

Ron Elderly: -

You Better Move On

No Expectations

Da Elderly: -

Tell Me Why

Southern Man

Only Love Can Break Your Heart

Birds*

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Sound Of Silence

True Love ways

If I Fell

So Sad

Out Of Time

The Habit was full from the off, with plenty of punters and players. Local maestro Chris Helme brought the house down with a magical rendition of Paul Simon's Peace Like A River and our host finished off the evening with his very own ribald version of Hallelujah.

Ron Elderly: -

You Better Move On

No Expectations

Da Elderly: -

Tell Me Why

Southern Man

Only Love Can Break Your Heart

Birds*

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Sound Of Silence

True Love ways

If I Fell

So Sad

Out Of Time

The Habit was full from the off, with plenty of punters and players. Local maestro Chris Helme brought the house down with a magical rendition of Paul Simon's Peace Like A River and our host finished off the evening with his very own ribald version of Hallelujah.

Not the same night, but you get the picture...

Some punters we were chatting to let it be known that they were Rolling Stones fans, so Ron obliged with a couple of numbers. In honour of the great man's recent birthday (71st), yours truly selected some songs from Neil Young's After The Gold Rush album, prompted by regular acapella singer Chris, who had asked me earlier to accompany him on Birds*. The Elderlys set contained songs that we haven't performed for a while - I totally messed up the intro to If I Fell, but recovered without too much damage being done. Thankfully Out Of Time went down a storm!!

Some punters we were chatting to let it be known that they were Rolling Stones fans, so Ron obliged with a couple of numbers. In honour of the great man's recent birthday (71st), yours truly selected some songs from Neil Young's After The Gold Rush album, prompted by regular acapella singer Chris, who had asked me earlier to accompany him on Birds*. The Elderlys set contained songs that we haven't performed for a while - I totally messed up the intro to If I Fell, but recovered without too much damage being done. Thankfully Out Of Time went down a storm!!

Wednesday, 16 November 2016

Tuesday, 15 November 2016

Bob Dylan: The 1966 Live Recordings

D.A. PENNEBAKER

Video A new short film made to accompany the release of the boxed set “Bob Dylan: The 1966 Live Recordings” features previously unseen footage of the tour, onstage and off, shot by D.A. Pennebaker.

Ben Sisario

The New York Times

10 November 2016

"THAT’S it — that sounds like the original,” Richard Alderson said, with a knowing nod.

Sitting in his living room in the West Village, Mr. Alderson was cranking up Bob Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” as recorded in Liverpool, England, on May 14, 1966, in a version never released before: raw and clear, direct from the tapes that Mr. Alderson made as the live-sound engineer for Mr. Dylan’s 1966 tour.

That tour, on which Mr. Dylan was backed up by musicians who became the Band, has attained almost mythic status as a tableau of confrontation, as Mr. Dylan’s folk fans rejected his embrace of electric rock ’n’ roll. In its most famous incident, an audience member in Manchester, England, blurted out, “Judas!” (In response, Mr. Dylan told his band to “play loud” — adding an expletive that made the instruction spiteful, joyous or both.)

Some of these shows have long circulated in bootleg versions. But on Friday, Columbia/Legacy will release every known recording from the tour as a 36-CD boxed set, “Bob Dylan: The 1966 Live Recordings,” most of which have never been heard in any form. It is a monumental addition to the corpus just as Mr. Dylan has been named the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The new boxed set is the latest archival release from Mr. Dylan, after “The Basement Tapes Complete” (six CDs) and “The Cutting Edge 1965-1966” (up to 18 CDs), that have been gobbled up by fans. For Mr. Dylan, there may also be a more prosaic motivation for the release: to secure European copyright protection on the recordings. (The works are eligible if released before they’re 50 years old.)

As the sound man, Mr. Alderson had a front-row seat on the historic tour. In an interview with The New York Times, and in a short film made by the record company, he reminisced about the demands of the job and the perplexing crowd reactions. The video includes previously unseen footage of the tour, onstage and off, shot by D. A. Pennebaker, who directed the film “Dont Look Back,” about Mr. Dylan’s 1965 tour.

Boxes of master audiotapes from 1966

A particular challenge of the 1966 tour, Mr. Alderson said, was building a sound system at a time when most theaters were ill equipped for a loud, amplified band.

“There was kind of no precedent for it,” Mr. Alderson, now 79, said as a terrier puppy yipped at his heels, and a pile of Dylan bootlegs sat on the coffee table for comparison.

The recordings trace Mr. Dylan’s tour through the United States, Australia, Britain and Europe, repeating the same two-part set with virtually no changes. In the first, acoustic half, he sang incantatory versions of “Visions of Johanna” and “Desolation Row”; for the second half, the entire band’s full-throttled takes on “Like a Rolling Stone” do not always drown out the jeers.

Even in the exhaustively documented field of Dylan studies, Mr. Alderson has been nearly lost in plain sight. He ran the tape machine for Mr. Dylan’s shows at the Gaslight Cafe in 1962 but was uncredited on the official release of those recordings in 2005. He also appears, unidentified, in “No Direction Home,” a documentary by Martin Scorsese that was also released that year. His name is barely in the Dylan history books (of which there are many).

“Nobody really wants to give me any credit,” Mr. Alderson said. “When I brought up the fact that I’m in the Scorsese film — I’m on screen with Dylan in some of the most important parts — the response was, ‘We thought it was some other Richard.’”

Mr. Alderson’s own career offers some explanation for the lapse. He was hired for the 1966 Dylan tour after recording Nina Simone at Carnegie Hall and building a live sound system for Harry Belafonte. After the tour ended, Mr. Dylan had a motorcycle accident and withdrew; Mr. Alderson ran his own studio — recording avant-garde jazz and rock bands like the Fugs — before burning out in 1969 and leaving for Mexico.

Richard Alderson, the sound engineer who recorded the performances on Mr. Dylan’s 1966 tour

FRED R. CONRAD FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

“I stayed in Mexico the entire time that Nixon was president,” Mr. Alderson said. “I completely lost touch with the New York recording scene.”

The audiotapes from the Dylan tour were made to accompany film footage being shot of the shows, some of which were used for the famously disjointed film “Eat the Document.”

Once the tour ended, Mr. Alderson turned over the tapes, which sat in refrigerated storage for five decades in Mr. Dylan’s extensive archives. Mr. Alderson reconnected with the Dylan circle over the last year as the boxed set came together, but his involvement was minimal. Until an interview with The Times, he had not heard the recordings in 50 years.

Richard Alderson, left, with Bob Dylan on tour in 1966.

D.A. PENNEBAKER

Speaking now, Mr. Alderson is still a little cranky but is clearly thrilled by the belated attention. He said that working with Mr. Dylan in 1966 was “more like working with a friend,” even though the video captures his old client bossing him around in no uncertain terms. And he doesn’t overthink the magic that went into capturing the tour on tape.

“You put good microphones up in front of good music,” Mr. Alderson says in the video, “and it sounds good.”

He was also careful to note his gratitude to Sony Music, the parent company of Columbia/Legacy, and to the Dylan camp for including his name in the official credits: “Mixing board tapes recorded by Richard Alderson.”

Sitting in his living room in the West Village, Mr. Alderson was cranking up Bob Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” as recorded in Liverpool, England, on May 14, 1966, in a version never released before: raw and clear, direct from the tapes that Mr. Alderson made as the live-sound engineer for Mr. Dylan’s 1966 tour.

That tour, on which Mr. Dylan was backed up by musicians who became the Band, has attained almost mythic status as a tableau of confrontation, as Mr. Dylan’s folk fans rejected his embrace of electric rock ’n’ roll. In its most famous incident, an audience member in Manchester, England, blurted out, “Judas!” (In response, Mr. Dylan told his band to “play loud” — adding an expletive that made the instruction spiteful, joyous or both.)

Some of these shows have long circulated in bootleg versions. But on Friday, Columbia/Legacy will release every known recording from the tour as a 36-CD boxed set, “Bob Dylan: The 1966 Live Recordings,” most of which have never been heard in any form. It is a monumental addition to the corpus just as Mr. Dylan has been named the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The new boxed set is the latest archival release from Mr. Dylan, after “The Basement Tapes Complete” (six CDs) and “The Cutting Edge 1965-1966” (up to 18 CDs), that have been gobbled up by fans. For Mr. Dylan, there may also be a more prosaic motivation for the release: to secure European copyright protection on the recordings. (The works are eligible if released before they’re 50 years old.)

As the sound man, Mr. Alderson had a front-row seat on the historic tour. In an interview with The New York Times, and in a short film made by the record company, he reminisced about the demands of the job and the perplexing crowd reactions. The video includes previously unseen footage of the tour, onstage and off, shot by D. A. Pennebaker, who directed the film “Dont Look Back,” about Mr. Dylan’s 1965 tour.

Boxes of master audiotapes from 1966

A particular challenge of the 1966 tour, Mr. Alderson said, was building a sound system at a time when most theaters were ill equipped for a loud, amplified band.

“There was kind of no precedent for it,” Mr. Alderson, now 79, said as a terrier puppy yipped at his heels, and a pile of Dylan bootlegs sat on the coffee table for comparison.

The recordings trace Mr. Dylan’s tour through the United States, Australia, Britain and Europe, repeating the same two-part set with virtually no changes. In the first, acoustic half, he sang incantatory versions of “Visions of Johanna” and “Desolation Row”; for the second half, the entire band’s full-throttled takes on “Like a Rolling Stone” do not always drown out the jeers.

Even in the exhaustively documented field of Dylan studies, Mr. Alderson has been nearly lost in plain sight. He ran the tape machine for Mr. Dylan’s shows at the Gaslight Cafe in 1962 but was uncredited on the official release of those recordings in 2005. He also appears, unidentified, in “No Direction Home,” a documentary by Martin Scorsese that was also released that year. His name is barely in the Dylan history books (of which there are many).

“Nobody really wants to give me any credit,” Mr. Alderson said. “When I brought up the fact that I’m in the Scorsese film — I’m on screen with Dylan in some of the most important parts — the response was, ‘We thought it was some other Richard.’”

Mr. Alderson’s own career offers some explanation for the lapse. He was hired for the 1966 Dylan tour after recording Nina Simone at Carnegie Hall and building a live sound system for Harry Belafonte. After the tour ended, Mr. Dylan had a motorcycle accident and withdrew; Mr. Alderson ran his own studio — recording avant-garde jazz and rock bands like the Fugs — before burning out in 1969 and leaving for Mexico.

Richard Alderson, the sound engineer who recorded the performances on Mr. Dylan’s 1966 tour

FRED R. CONRAD FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

“I stayed in Mexico the entire time that Nixon was president,” Mr. Alderson said. “I completely lost touch with the New York recording scene.”

The audiotapes from the Dylan tour were made to accompany film footage being shot of the shows, some of which were used for the famously disjointed film “Eat the Document.”

Once the tour ended, Mr. Alderson turned over the tapes, which sat in refrigerated storage for five decades in Mr. Dylan’s extensive archives. Mr. Alderson reconnected with the Dylan circle over the last year as the boxed set came together, but his involvement was minimal. Until an interview with The Times, he had not heard the recordings in 50 years.

Richard Alderson, left, with Bob Dylan on tour in 1966.

D.A. PENNEBAKER

Speaking now, Mr. Alderson is still a little cranky but is clearly thrilled by the belated attention. He said that working with Mr. Dylan in 1966 was “more like working with a friend,” even though the video captures his old client bossing him around in no uncertain terms. And he doesn’t overthink the magic that went into capturing the tour on tape.

“You put good microphones up in front of good music,” Mr. Alderson says in the video, “and it sounds good.”

He was also careful to note his gratitude to Sony Music, the parent company of Columbia/Legacy, and to the Dylan camp for including his name in the official credits: “Mixing board tapes recorded by Richard Alderson.”

Monday, 14 November 2016

Leon Russell RIP

Jon Pareles

The New York Times

13 November 2016

Leon Russell, the longhaired, scratchy-voiced pianist, guitarist, songwriter and bandleader who moved from playing countless recording sessions to making hits on his own, died on Sunday in Nashville. He was 74.

His website said he had died in his sleep but gave no specific cause.

Mr. Russell’s health had incurred significant setbacks in recent years. In 2010, he underwent surgery for a brain fluid leak and was treated for heart failure. In July he had a heart attack and was scheduled for further surgery, according to a news release from the historical society of Oklahoma, his home state.

With his trademark top hat, hair well past his shoulders, a long, lush beard, an Oklahoma drawl and his fingers splashing two-fisted barrelhouse piano chords, Mr. Russell cut a flamboyant figure in the early 1970s. He led Joe Cocker’s band Mad Dogs & Englishmen, appeared at George Harrison’s 1971 Concert for Bangladesh in New York City and had numerous hits of his own, including “Tight Rope.”

Many of his songs became hits for others, among them “Superstar” (written with Bonnie Bramlett) for the Carpenters, “Delta Lady” for Mr. Cocker and “This Masquerade” for George Benson. More than 100 acts have recorded“A Song for You,” which Mr. Russell said he wrote in 10 minutes.

By the time he released his first solo album, in 1970, he had already played on hundreds of songs as one of the top studio musicians in Los Angeles. He was in Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound Orchestra, and he played sessions for Frank Sinatra, Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, the Ventures and the Monkees, among many others. His piano playing is heard on “Mr. Tambourine Man” by the Byrds, “A Taste of Honey” by Herb Alpert, “Live With Me” by the Rolling Stones and all of the Beach Boys’ early albums, including “Pet Sounds.”

The music Mr. Russell made on his own put a scruffy, casual surface on rich musical hybrids, interweaving soul, country, blues, jazz, gospel, pop and classical music. Like Willie Nelson, who collaborated with him, and Ray Charles, whose 1993 recording of “A Song for You” won a Grammy Award, Mr. Russell made a broad, sophisticated palette of American music sound down-home and natural.Photo

After his popularity had peaked in the 1970s, he shied away from self-promotion and largely set aside rock, though he kept performing. But he was prized as a musicians’ musician, collaborating with Elvis Costello and Elton John, among others. In 2011, after making a duet album with Mr. John, “The Union,” he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. At the ceremony, Mr. John called him “the master of space and time”and added, “He sang, he wrote and he played just how I wanted to do it.”

Leon Russell was born Claude Russell Bridges in Lawton, Okla., on April 2, 1942. An injury to his upper vertebrae at birth caused a slight paralysis on his right side that would shape his music: A resulting delayed reaction time in his right hand forced him to think ahead about what it would play. “It gave me a very strong sense of duality,” he said last year in a Public Radio International interview.

He started classical piano lessons when he was 4, played baritone horn in his high school marching band and also learned trumpet. At 14 he started gigging in Oklahoma; since it was a dry state at the time, he could play clubs without being old enough to drink. Soon after he graduated from high school, Jerry Lee Lewis hired him and his band to back him on tour for two months.

He moved to Los Angeles in the late 1950s and found club work and then studio work; he learned to play guitar, and he began calling himself Leon Russell, taking the name Leon from a friend who had lent him an ID so he could play California club dates while underage.

His music-making drew on both his classical training and his Southern roots, and he played everything from standards to surf-rock, from million-sellers to pop throwaways. He was glimpsed on television as a member of the Shindogs, the house band for the prime-time rock show “Shindig!” in the mid-1960s, and was in the house band for the 1964 concert film, “The T.A.M.I. Show.”

In 1967, he built a home studio and began working with the guitarist Marc Benno as the Asylum Choir, which released its debut album in 1968. He also started a record label, Shelter, in 1969 with the producer Denny Cordell. Mr. Russell drew more recognition as a co-producer, arranger and musician on Mr. Cocker’s second album, “Joe Cocker!,” which included Mr. Russell’s song “Delta Lady.”

When Mr. Cocker’s Grease Band fell apart days before an American tour, Mr. Russell assembled Mad Dogs & Englishmen, a big, boisterous band that included three drummers and a 10-member choir. Its 1970 double live album and a tour film became a showcase for Mr. Russell as well as for Mr. Cocker; the album reached No. 2 on the Billboard album chart.Photo