Wes Craven, Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream director, dies at 76

Veteran Hollywood horror director, who made the A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream film franchises, dies after being diagnosed with brain cancer

Monica Tan

Monday 31 August 2015

Wes Craven, veteran writer and director of some of Hollywood’s most famous successful film franchises, has died at the age of 76.

The director of A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream died on Sunday night at his Los Angeles home after being diagnosed with brain cancer, the Hollywood Reporter confirmed.

Craven was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and directed his first feature film, The Last House on the Left, in 1972 following a master’s degree in philosophy and writing at Johns Hopkins University and an early career in teaching.

With 1982’s Swamp Thing, Craven moved into directing big-budget films, and had a huge hit when he wrote and directed A Nightmare on Elm Street two years later.

The popularity of the film and its terrifying antagonist Freddy Krueger established Craven’s reputation as a director of the teen slashers, able to blend gore with wry humour and create memorable film villains.

His mantle as the king of horror continued throughout the 90s, with his Scream franchise setting the tone for numerous imitators. Scream took $173m in worldwide box office takings, with its 1997 sequel falling just short of half a million in matching its predecessor.

Craven only occasionally strayed from the horror genre, including the sentimental Music of the Heart starring Meryl Streep, and his 2005 psychological thriller Red Eye.

Director of Bridesmaids and the Ghostbusters reboot Paul Feig tweeted his respects, calling Craven “one of a kind” and thanking him for “all the years of scares and fun”. Leigh Whannell, co-creator of the blockbuster horror film franchise Saw, tweeted: “any horror fan says goodbye to Wes Craven with a heavy heart. He gifted my generation with so many memories”.

Actor Rose McGowan tweeted that Craven was “the kindest man, the gentlest man, and one of the smartest men I’ve known” and hoped the news had “a plot twist”.

Jamie Kennedy, who played Randy Meeks in Scream, credited Craven with launching his career. “Thank you for believing in me and giving me a chance,” he tweeted.

Craven was remembered for uncovering fresh talent, casting a relatively unknown Johnny Depp for A Nightmare on Elm Street and is credited with giving Sharon Stone (Deadly Blessing, 1981) and Bruce Willis (an episode of The Twilight Zone) their first featured roles.

In a 2014 interview with Filmmaker Magazine, Craven said he was amazed by A Nightmare on Elm Street’s longevity in popular culture. He reflected on his life and career, including leaving graduate school having only seen “maybe three films in the theatre” due to his strict religious upbringing.

His move to a small town in upstate New York, where he frequented an art theatre that showed European films, set him on a new career course. “It just knocked me off my chair, the imagination and everything … guys like Bergman and Fellini really appealed to me and the idea of film-making just somehow rang my bell,” he said.

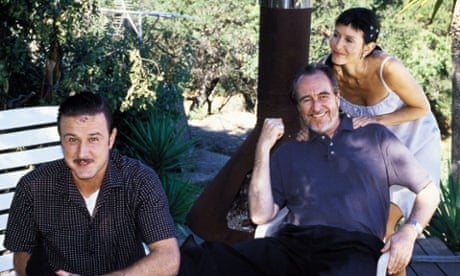

Craven is survived by his wife, Iya Labunka, a film producer and production manager. The pair were married in 2004 and worked together on 2011’s Scream 4. He has two children, Jonathan and Jessica Craven, from his first marriage to Bonnie Broecker. He also has a stepdaughter, Nina Tarnawsky.

http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/aug/31/wes-craven-nightmare-on-elm-street-and-scream-director-dies-at-76

Veteran Hollywood horror director, who made the A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream film franchises, dies after being diagnosed with brain cancer

Monica Tan

Monday 31 August 2015

Wes Craven, veteran writer and director of some of Hollywood’s most famous successful film franchises, has died at the age of 76.

The director of A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream died on Sunday night at his Los Angeles home after being diagnosed with brain cancer, the Hollywood Reporter confirmed.

Craven was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and directed his first feature film, The Last House on the Left, in 1972 following a master’s degree in philosophy and writing at Johns Hopkins University and an early career in teaching.

With 1982’s Swamp Thing, Craven moved into directing big-budget films, and had a huge hit when he wrote and directed A Nightmare on Elm Street two years later.

The popularity of the film and its terrifying antagonist Freddy Krueger established Craven’s reputation as a director of the teen slashers, able to blend gore with wry humour and create memorable film villains.

His mantle as the king of horror continued throughout the 90s, with his Scream franchise setting the tone for numerous imitators. Scream took $173m in worldwide box office takings, with its 1997 sequel falling just short of half a million in matching its predecessor.

Craven only occasionally strayed from the horror genre, including the sentimental Music of the Heart starring Meryl Streep, and his 2005 psychological thriller Red Eye.

Director of Bridesmaids and the Ghostbusters reboot Paul Feig tweeted his respects, calling Craven “one of a kind” and thanking him for “all the years of scares and fun”. Leigh Whannell, co-creator of the blockbuster horror film franchise Saw, tweeted: “any horror fan says goodbye to Wes Craven with a heavy heart. He gifted my generation with so many memories”.

Actor Rose McGowan tweeted that Craven was “the kindest man, the gentlest man, and one of the smartest men I’ve known” and hoped the news had “a plot twist”.

Jamie Kennedy, who played Randy Meeks in Scream, credited Craven with launching his career. “Thank you for believing in me and giving me a chance,” he tweeted.

Craven was remembered for uncovering fresh talent, casting a relatively unknown Johnny Depp for A Nightmare on Elm Street and is credited with giving Sharon Stone (Deadly Blessing, 1981) and Bruce Willis (an episode of The Twilight Zone) their first featured roles.

In a 2014 interview with Filmmaker Magazine, Craven said he was amazed by A Nightmare on Elm Street’s longevity in popular culture. He reflected on his life and career, including leaving graduate school having only seen “maybe three films in the theatre” due to his strict religious upbringing.

His move to a small town in upstate New York, where he frequented an art theatre that showed European films, set him on a new career course. “It just knocked me off my chair, the imagination and everything … guys like Bergman and Fellini really appealed to me and the idea of film-making just somehow rang my bell,” he said.

Craven is survived by his wife, Iya Labunka, a film producer and production manager. The pair were married in 2004 and worked together on 2011’s Scream 4. He has two children, Jonathan and Jessica Craven, from his first marriage to Bonnie Broecker. He also has a stepdaughter, Nina Tarnawsky.

Wes Craven: the mainstream horror maestro inspired by Ingmar Bergman

It was the Swedish auteur who prompted the late director to pursue a career in movie-making. His influence can be traced right through Craven’s brilliant, chilling career

Peter Bradshaw

Monday 31 August 2015

Wes Craven’s career is a startling link between the European arthouse and Hollywood exploitation horror. This was no movie brat, growing up obsessively watching movies on VHS, getting steeped in trash-celluloid lore, knowing scenes by heart and shooting his own homemade version on Super 8 at the age of nine in the way we might expect of a hugely successful genre director.

In any case, his upbringing was before the era of video (he was born in 1939) and his strictly religious parents hardly let him go to the cinema at all. In fact, after an initial plan to go into teaching, Craven’s move to New York from his hometown of Cleveland as a young man introduced him to arthouse theatres where he was electrified by the work of directors like Ingmar Bergman: it was this that inspired him to go into film-making and he had the idea of remaking Bergman’s 1960 film Virgin Spring as The Last House on the Left in 1972 — three years before Woody Allen’s Love and Death pastiched Bergman, among other high European masters, in an obviously cod-reverential way.

Craven took from Virgin Spring the idea of people enacting revenge for the rape and murder of their daughter, but in a more obviously secularised, ironised and sensational style. Wes Craven could be said to have invented, or at least popularised the modern rape-revenge genre and ironically did so in the same era when the name “Bergman” became a widely understood talk-show punchline for jokes about Hollywood trash vs highbrow Europeans.

Despite helping Meryl Streep to an Oscar nomination with his atypical 1999 movie Music of the Heart, a syrupy film about an inspirational teacher, Craven of course became a horror maestro, with a flair for developing sequel-spawning properties. He began his career with the potent, influential The Hills Have Eyes about the family being targeted by a sinister group in the desert.

But it was his great franchises Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream (co-written with Kevin Williamson) which gave him his legendary status. Nightmare on Elm Street was an endlessly quotable, malleable phrase for headline-writers all over the English-speaking world, especially in the UK where “Elm” was always being replaced with “Downing”. Each franchise crucially had its horribly familiar, nightmarishly recognisable villain-hero: Freddy Krueger and Ghostface.

Nightmare on Elm Street had the brilliant idea of the demon haunting one’s dreams – that grotesque figure in a hat, burned face and clawed glove. The young Johnny Depp was in the first Nightmare: did Freddy Krueger inspire a kind of romanticised, Jekyllised version in Edward Scissorhands? Nightmare collapsed the distinction between dreams and reality, and perhaps even hinted at an awareness of the horror genre’s own status as the culturally licensed bad dream.

But it was actually Scream which was the really playfully self-referential movie series, a franchise which became a key text for the 1990s fashion for postmodernism and all things meta. It spoofed and pastiched the scary genre itself, drawing attention to its own tropes and tricks, knowingly tipping the wink to fans. The title was originally going to be Scary Movie, a tag gratefully picked up by the Wayans brothers in their own out-and-out send-up movie series.

Again, Craven was a pioneer: he popularised this element of sophistication, laying the groundwork for a picture like, say, The Cabin in the Woods, scripted by Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard. But Scream isn’t just a comedy. There is something genuinely disturbing about the elongated dropped jaw of Ghostface, distended in its endless silent scream. When I saw this film first, I thought of the ghost of Jacob Marley in A Christmas Carol: taking off the bandage around his head, his lower jaw drops down to his chest.

Not everyone admired Craven’s style. David Thomson wrote: “… the postmodern self-reflection of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare and the Scream pictures … amounts to a frenzied redoubling of nastiness because no one really believes in it.” Well, it is an accusation which could be perennially levelled at all horror movies or even fairground rides: dark, scary thrills do not have much in the way of moral edification. But horror films can be lethally brilliant, immersive experiences. Those are what Wes Craven provided.

It was the Swedish auteur who prompted the late director to pursue a career in movie-making. His influence can be traced right through Craven’s brilliant, chilling career

Peter Bradshaw

Monday 31 August 2015

Wes Craven’s career is a startling link between the European arthouse and Hollywood exploitation horror. This was no movie brat, growing up obsessively watching movies on VHS, getting steeped in trash-celluloid lore, knowing scenes by heart and shooting his own homemade version on Super 8 at the age of nine in the way we might expect of a hugely successful genre director.

In any case, his upbringing was before the era of video (he was born in 1939) and his strictly religious parents hardly let him go to the cinema at all. In fact, after an initial plan to go into teaching, Craven’s move to New York from his hometown of Cleveland as a young man introduced him to arthouse theatres where he was electrified by the work of directors like Ingmar Bergman: it was this that inspired him to go into film-making and he had the idea of remaking Bergman’s 1960 film Virgin Spring as The Last House on the Left in 1972 — three years before Woody Allen’s Love and Death pastiched Bergman, among other high European masters, in an obviously cod-reverential way.

Craven took from Virgin Spring the idea of people enacting revenge for the rape and murder of their daughter, but in a more obviously secularised, ironised and sensational style. Wes Craven could be said to have invented, or at least popularised the modern rape-revenge genre and ironically did so in the same era when the name “Bergman” became a widely understood talk-show punchline for jokes about Hollywood trash vs highbrow Europeans.

Despite helping Meryl Streep to an Oscar nomination with his atypical 1999 movie Music of the Heart, a syrupy film about an inspirational teacher, Craven of course became a horror maestro, with a flair for developing sequel-spawning properties. He began his career with the potent, influential The Hills Have Eyes about the family being targeted by a sinister group in the desert.

But it was his great franchises Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream (co-written with Kevin Williamson) which gave him his legendary status. Nightmare on Elm Street was an endlessly quotable, malleable phrase for headline-writers all over the English-speaking world, especially in the UK where “Elm” was always being replaced with “Downing”. Each franchise crucially had its horribly familiar, nightmarishly recognisable villain-hero: Freddy Krueger and Ghostface.

Nightmare on Elm Street had the brilliant idea of the demon haunting one’s dreams – that grotesque figure in a hat, burned face and clawed glove. The young Johnny Depp was in the first Nightmare: did Freddy Krueger inspire a kind of romanticised, Jekyllised version in Edward Scissorhands? Nightmare collapsed the distinction between dreams and reality, and perhaps even hinted at an awareness of the horror genre’s own status as the culturally licensed bad dream.

But it was actually Scream which was the really playfully self-referential movie series, a franchise which became a key text for the 1990s fashion for postmodernism and all things meta. It spoofed and pastiched the scary genre itself, drawing attention to its own tropes and tricks, knowingly tipping the wink to fans. The title was originally going to be Scary Movie, a tag gratefully picked up by the Wayans brothers in their own out-and-out send-up movie series.

Again, Craven was a pioneer: he popularised this element of sophistication, laying the groundwork for a picture like, say, The Cabin in the Woods, scripted by Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard. But Scream isn’t just a comedy. There is something genuinely disturbing about the elongated dropped jaw of Ghostface, distended in its endless silent scream. When I saw this film first, I thought of the ghost of Jacob Marley in A Christmas Carol: taking off the bandage around his head, his lower jaw drops down to his chest.

Not everyone admired Craven’s style. David Thomson wrote: “… the postmodern self-reflection of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare and the Scream pictures … amounts to a frenzied redoubling of nastiness because no one really believes in it.” Well, it is an accusation which could be perennially levelled at all horror movies or even fairground rides: dark, scary thrills do not have much in the way of moral edification. But horror films can be lethally brilliant, immersive experiences. Those are what Wes Craven provided.

No comments:

Post a Comment