Self-Portrait as a Painter (1887-88) by Vincent van Gogh; and Self-Portrait with Palette (1926) by Edvard Munch.

Side by side, Edvard Munch and Vincent van Gogh scream the birth of expressionism

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

The exhibition Munch: Van Gogh shows the two artists, who never met, shared a passionate desire to paint the savage intensity of life – and it casts fresh light on the Dutchman’s tragedy

Jonathan Jones

Wednesday 23 September 2015

A gunshot and a scream reverberate through the yellow house, echo across the fjord, and fill a new exhibition at the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam with pity and terror.

In 1890 Vincent van Gogh fatally shot himself in the French countryside. Three years later the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch was walking near Oslo’s fjord at sunset. As the sun went down, he remembered years later, he was seized by a dreadful vision:

“The air became like blood – with piercing strands of fire ... I felt a great scream – and I actually heard a great scream.”

Wednesday 23 September 2015

A gunshot and a scream reverberate through the yellow house, echo across the fjord, and fill a new exhibition at the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam with pity and terror.

In 1890 Vincent van Gogh fatally shot himself in the French countryside. Three years later the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch was walking near Oslo’s fjord at sunset. As the sun went down, he remembered years later, he was seized by a dreadful vision:

“The air became like blood – with piercing strands of fire ... I felt a great scream – and I actually heard a great scream.”

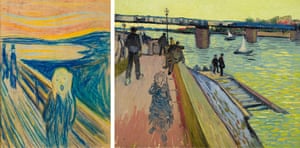

Munch’s 1893 crayon drawing The Scream, on loan from Oslo’s Munch Museum, now hangs near Van Gogh’s Wheatfield under Thunderclouds, which he painted in the last months of his life. The sky for Van Gogh has become a gorgeously thick and wet, yet oppressively dense and massive smear of blue and white. Meanwhile the sky for Munch, in The Scream, is a sinister aurora borealis, a radioactive blaze. We are left to guess what Van Gogh’s blue soup of a sky says about his emotional state. Munch leaves no such ambiguity. He portrays himself as a robed, monk-like figure, his eyes dots of pain in a hairless skull, his mouth an oval of anguish.

Other walkers stand insensitive before the fjord. Only the isolated artist can hear the scream that is tearing nature itself apart.

Seeing Munch and Van Gogh side by side is a journey to the birth of expressionism. They never met, and Van Gogh never knew Munch existed – although Munch, who lived until 1944, certainly got to know eventually about Van Gogh. Yet both artists intuited something similar. They felt the world crying out to express itself in colours. They heard a music, or a scream, in nature that connected artist and sky, artist and fields. The way they set down this holistic, extreme sensitivity created a new kind of art.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Yellow House (1888); and Red Virginia Creeper (1898-1900), by Edvard Munch

Munch: Van Gogh compares some of the greatest masterpieces of two of the greatest modern artists. Munch, besides one of his four versions of The Scream, is represented by his even more terrifying vision of a house that seems to drip blood, Red Virginia Creeper (1898-1900), his darkly erotic Madonna (1895-97), and many more such shocking revelations of the fin de siecle. Van Gogh replies with works like Starry Night over the Rhone (1888) and The Yellow House (1888). It is like a drama by Strindberg in which the two most intense artists who ever lived rage in mutual madness.

Munch - Starry Night, 1922-1924

Van Gogh - Starry Night over Rhone, 1888

Munch was the friend Van Gogh never found. The one man who might have understood him. When he rented the Yellow House in Arles and decorated it with bright paintings of sunflowers, Van Gogh was dreaming of utopia. He hoped this house would become an art colony where painters worked like brothers. Instead he got Paul Gauguin as a house guest and the dream ended in self harm and hospitalisation. Would Munch have been a better painting companion? In his 1889 painting Summer Night: Inger on the Beach, nature is a numinous, living presence that infuses the painting with inner light, just as Van Gogh’s stars spark in the blue.

Both these northerners were set alight by French impressionism and both admired Gauguin’s abstract, symbolic boldness. Munch’s nightmarish lithographs of lonely souls and depraved sexuality owe more to Gauguin than Van Gogh does, even though it was Van Gogh who lived with Gauguin. But the similarities between Munch and Van Gogh are ultimately less telling than their differences.

This exhibition casts a radically new light on the tragedy of Van Gogh. If a psychiatrist were asked which of these painters was affected by mental health issues, which was most troubled, the diagnosis would be easy. Obviously, Munch is the morbid, seriously disturbed artist here. It is Munch who wears sickness on his sleeve. It’s not just his self-portrait as a screaming ghoul. What about his print Jealousy, in which a bearded youth gazes big-eyed into nothingness while a woman shows her body to a voyeuristic man? Or Red Virginia Creeper, in which blood covers a house and seeps into a muddy path, while the same tortured face gazes into an abyss of horror?

By comparison Van Gogh is free from all morbidity, despair, or self-pity. He liked to close his letters “with a handshake” and recommended smoking a pipe, like he did, to stay sane and happy. His paintings, next to those of Munch, are golden dreams of harmony and hope. He sees a magic in nature, a divine energy. The sound he hears is not a scream but a shout of exultation.

Munch is a macabre poet of darkness, vampires, murder. His art is erotic and perverse. Van Gogh, in the cornfield, is a believer. He is all love.

Until the crows come screaming.

Munch: Van Gogh is at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, from 25 September to 17 January 2016

No comments:

Post a Comment