Brian Sewell's pungent views got people arguing – that’s what matters

The controversial art critic railed against so many things because he knew newspapers and criticism should be great popular entertainment

Jonathan Jones

Sunday 20 September 2015

Newspapers – and critics – love to pretend otherwise, sometimes even headlining the opinions of their arts commentators as “verdicts” as if we were high court judges, but in reality, a review at its best is just a bloody good read. It is a stimulating, provocative or plain annoying blast of verbal adrenalin whose purpose is to create enjoyable discussion about the arts, not to make or break artists in some terrifying Old Testament way.

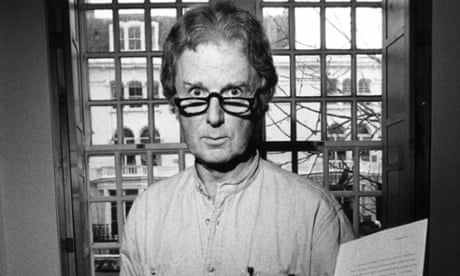

Brian Sewell, who has died aged 84, understood that and played the part of a critic brilliantly. He was the profession’s equivalent of Dame Maggie Smith in Downton Abbey, a hugely entertaining old monster. His ratings were on the Downton scale too. He was genuinely loved by legions of readers, a national celebrity. The first time I ever met him, as we waited to board a train in the early morning, a commuter came up to him to thank him for his work. That kind of enthusiasm is rare for a reviewer to experience and it was genuine and very widely shared.

When we got on the train, he said he enjoyed my work but he had imagined me as someone much younger. I sensed he also meant better looking. He was disappointed I was not someone he could take under his wing. And he was comically open about that. Sewell was as uncensored in person as he was in print.

His act may have matched the posh bitchiness of Lady Grantham but it also anticipated Jeremy Corbyn’s less elegant “authenticity” roadshow. Sewell’s own highest value as a critic was “honesty”. He believed it was honesty that distinguished him from the rivals he saw as mealy-mouthed frauds. He reviled Andrew Graham-Dixon and Waldemar Januszczak in an absurdly mean way. That was part of his honesty, as was expressing outrageous opinions that – he believed – others shared but feared to utter. Try this one for size:

“Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness. Women make up 50% or more of classes at art school. Yet they fade away in their late 20s or 30s. Maybe it’s something to do with bearing children.”

The problem with this opinion is not that it is offensive but that it is nonsense. It’s a load of cobblers. It was also baloney for Sewell to refuse to see the merits of great modern artists like Cy Twombly. He once upbraided me in person for writing an article in praise of Twombly. He couldn’t distinguish between overhyped artists who deserved to be shot down and the true modern greats. His vision, as a critic, was narrowed by this blindness to what is powerful in modern art. He had a very silly side. But so what? His views were pungent and got people arguing and that’s what matters.

We are constantly being told criticism is dead but Brian Sewell disproved that spectacularly by making himself famous for being a critic and always a critic. He was as well known for being Mr Nasty as the judges on reality television shows. The delight audiences take in seeing Paul Hollywood devastatingly dismiss a meringue is another proof that criticism is very much alive – and Sewell had the same popular appeal. Criticism is a healthy symptom of a democratic society and has been since the 18th century when reviews started appearing in magazines and newspapers. Brian Sewell kept the art of reviewing alive with panache. He is being mourned as a brave anti-populist. Actually he was a great populist.

He invented his act before the internet age, yet anticipated this new era’s appetite for provocation and argument. Sewell had the good fortune to be denouncing conceptual art in the early 90s at a time when Damien Hirst, Charles Saatchi and the Turner prize were making it notorious as never before. The Young British Artists, as much as anyone else, needed someone to express total hostility to their work, to act out the part of the arch conservative. They thrived on controversy, and so did he. Sewell slagged off trendy art far more wittily than typical conservatives who merely sounded old and tired. He assailed the schlock of the new with energy and glee. He was Punch to Tracey Emin’s Judy.

Like a thread of 10,000 hostile online comments might be today, the letter was the making of him

It was naive of art world types to write a letter to the Evening Standard in 1994 denouncing him. Like a thread of 10,000 hostile online comments might be today, it was the making of him. Sewell really scared these people, it seemed. But by the time he stopped writing he was beloved by many in the same art world that once loathed him. Contemporary art triumphed and Sewell could not stop it. Not a single word he wrote held back a Hirst or Perry or Banksy. Knowing his words were harmless, artists came to enjoy them more than anyone.

That is what I mean about Sewell being a great entertainer.

The truth is that he is as much part of the history of modern British art as any artist he dismissed. He helped to make modern art the mass entertainment we know, love or loathe. Criticism is much poorer without him, as is his former paper the Evening Standard. How will it replace such a distinctive voice? Will any paper even try to? We were royally entertained. May the old bastard rest in peace.

The controversial art critic railed against so many things because he knew newspapers and criticism should be great popular entertainment

Jonathan Jones

Sunday 20 September 2015

Newspapers – and critics – love to pretend otherwise, sometimes even headlining the opinions of their arts commentators as “verdicts” as if we were high court judges, but in reality, a review at its best is just a bloody good read. It is a stimulating, provocative or plain annoying blast of verbal adrenalin whose purpose is to create enjoyable discussion about the arts, not to make or break artists in some terrifying Old Testament way.

Brian Sewell, who has died aged 84, understood that and played the part of a critic brilliantly. He was the profession’s equivalent of Dame Maggie Smith in Downton Abbey, a hugely entertaining old monster. His ratings were on the Downton scale too. He was genuinely loved by legions of readers, a national celebrity. The first time I ever met him, as we waited to board a train in the early morning, a commuter came up to him to thank him for his work. That kind of enthusiasm is rare for a reviewer to experience and it was genuine and very widely shared.

When we got on the train, he said he enjoyed my work but he had imagined me as someone much younger. I sensed he also meant better looking. He was disappointed I was not someone he could take under his wing. And he was comically open about that. Sewell was as uncensored in person as he was in print.

His act may have matched the posh bitchiness of Lady Grantham but it also anticipated Jeremy Corbyn’s less elegant “authenticity” roadshow. Sewell’s own highest value as a critic was “honesty”. He believed it was honesty that distinguished him from the rivals he saw as mealy-mouthed frauds. He reviled Andrew Graham-Dixon and Waldemar Januszczak in an absurdly mean way. That was part of his honesty, as was expressing outrageous opinions that – he believed – others shared but feared to utter. Try this one for size:

“Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness. Women make up 50% or more of classes at art school. Yet they fade away in their late 20s or 30s. Maybe it’s something to do with bearing children.”

The problem with this opinion is not that it is offensive but that it is nonsense. It’s a load of cobblers. It was also baloney for Sewell to refuse to see the merits of great modern artists like Cy Twombly. He once upbraided me in person for writing an article in praise of Twombly. He couldn’t distinguish between overhyped artists who deserved to be shot down and the true modern greats. His vision, as a critic, was narrowed by this blindness to what is powerful in modern art. He had a very silly side. But so what? His views were pungent and got people arguing and that’s what matters.

We are constantly being told criticism is dead but Brian Sewell disproved that spectacularly by making himself famous for being a critic and always a critic. He was as well known for being Mr Nasty as the judges on reality television shows. The delight audiences take in seeing Paul Hollywood devastatingly dismiss a meringue is another proof that criticism is very much alive – and Sewell had the same popular appeal. Criticism is a healthy symptom of a democratic society and has been since the 18th century when reviews started appearing in magazines and newspapers. Brian Sewell kept the art of reviewing alive with panache. He is being mourned as a brave anti-populist. Actually he was a great populist.

He invented his act before the internet age, yet anticipated this new era’s appetite for provocation and argument. Sewell had the good fortune to be denouncing conceptual art in the early 90s at a time when Damien Hirst, Charles Saatchi and the Turner prize were making it notorious as never before. The Young British Artists, as much as anyone else, needed someone to express total hostility to their work, to act out the part of the arch conservative. They thrived on controversy, and so did he. Sewell slagged off trendy art far more wittily than typical conservatives who merely sounded old and tired. He assailed the schlock of the new with energy and glee. He was Punch to Tracey Emin’s Judy.

Like a thread of 10,000 hostile online comments might be today, the letter was the making of him

It was naive of art world types to write a letter to the Evening Standard in 1994 denouncing him. Like a thread of 10,000 hostile online comments might be today, it was the making of him. Sewell really scared these people, it seemed. But by the time he stopped writing he was beloved by many in the same art world that once loathed him. Contemporary art triumphed and Sewell could not stop it. Not a single word he wrote held back a Hirst or Perry or Banksy. Knowing his words were harmless, artists came to enjoy them more than anyone.

That is what I mean about Sewell being a great entertainer.

The truth is that he is as much part of the history of modern British art as any artist he dismissed. He helped to make modern art the mass entertainment we know, love or loathe. Criticism is much poorer without him, as is his former paper the Evening Standard. How will it replace such a distinctive voice? Will any paper even try to? We were royally entertained. May the old bastard rest in peace.

No comments:

Post a Comment