Faithful and Disappointing

The Importance of Elsewhere - Philip Larkin’s Photographs, Richard Bradford, Frances Lincoln, 2015, 208pp, £25 (hardcover)

Larkin’s friend and early publisher Jean Hartley always maintained that it was Maeve Brennan, not Monica Jones, who was the great love of Larkin’s life. Certainly, the photographs the poet took of both women are a study in contrasts. A typical early portrait of Monica in the book shows the flamboyant university lecturer in her office at Leicester in 1947; arms folded assertively, a cigarette between her fingers, while directing her trademark unflinching stare at the camera. At least early on in their relationship, Larkin would carefully construct his portraits of Monica, including a highly stylised photograph in the garden of her Leicester flat. The picture prompted Larkin to reveal, in a letter to his lover in January 1951, that the dress she wore ‘arouses the worst in me’. But it’s also fair to say that as Monica aged and gained weight, Larkin’s photographs of her became more casual and less erotically charged. (A quotation from his poem, ‘Lines on a Young Lady’s Photograph Album,’ is relevant here: ‘But o, photography! as no art is,/Faithful and disappointing!’) In stark contrast, Larkin’s pictures of Maeve are far less obviously sexual, presenting his later love interest as pure, like an idealised, muse-like figure. Although the pictures are warm and intimate, they also capture something of the personal and moral reticence of the devout Roman Catholic. For example, Larkin photographed Maeve staring through long grass in 1961, suggesting her reserved, unobtainable quality. For Bradford, Maeve was ‘plain, bright enough but unsophisticated,’ speculating the poet was attracted to his library colleague precisely because of her objections to sex outside marriage. Contrasting the two women in Larkin’s life, Bradford believes that ‘Monica challenged him, intellectually and emotionally, while Maeve mirrored the parts of his temperament that he had largely concealed or subdued, particularly his crippling anxiety, shyness and insularity.’ The author believes Maeve is often photographed ‘in an Edwardian time warp,’ adding, rather cruelly, that ‘Larkin took care to capture a physiognomy that was not classically handsome, one which combined the combative features of maleness with a weary acceptance of middle age’ In fact, some of the pictures of Maeve in the book contradict this blunt estimate. In most of the photographs featured, Maeve is smiling naturally and unaffectedly for the camera, for example, in a hotel in Hornsea or in the countryside. While Bradford calls Maeve ‘happily uncultured’ in such pictures, there is an undeniable emotional warmth in the portraits, as though Larkin is also smiling behind the camera. But it’s difficult to find a photograph of a smiling Monica.

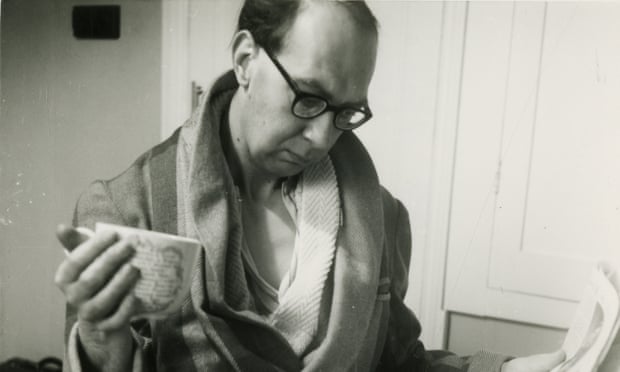

Larkin’s photographic self-portraits possess a haunted, Hopperesque quality. Never at ease with his own appearance, this physical disquiet is reflected in his pictures. But he persisted in taking photographs of himself with a timer, suggesting either an abiding need for self analysis, a desire to sharpen his camera skills or simple egotism. In one of his earliest self-portraits, taken in his room at St John’s, Oxford, Larkin is reflected in a mirror, the young poet looking suitably introspective. When not taking bleak, existential pictures of his empty bedrooms in Belfast or Pearson Park, Hull - which are almost visual evocations of the poem ‘Mr Bleaney’ - a typically glum Larkin is pictured holding a wicker rabbit, in a picture sequence taken by Monica in 1962. But good as some of Larkin’s interior shots and portraits are, his pictures of street scenes are some of the strong- est images in the book. These include an evocative study - inscribed ‘To the Match’- taken in 1949, showing Leicester City fans on their way to the Filbert Street ground, wrapped in a ghostly half-light. Larkin’s time in Belfast proved extremely fruitful for both his poetry and photography. There are several pictures of mass marches through the streets of Belfast and of the Walls of Derry. A return visit to Ireland by Larkin in 1969 produced more striking images, including a colour shot of Belfast before the 12 July festivities. Also featured are some of the idyllic rural scenes Larkin photographed in the East Riding countryside, including Laxton, Yokefleet, Kilpin and Faxfleet, the images providing a lush, visual complement to lyrically upbeat poems such as ‘Cut Grass’ and ‘The Trees.’

But there’s also a sense that as Larkin’s poetic muse abandoned him, his interest in photography also waned. Some of the final pictures in Brad- ford’s book have a casual, almost throwaway quality. And the starkness of Larkin’s later verse, most notably the death-obsessed ‘Aubade,’ finds a visual equivalent in the book’s final, echoing images. One photograph shows the older Monica Jones, wearing a rather frumpy dress, staring blankly out of a window, while the adjacent picture captures Larkin’s mother, Eva, shortly before her death, staring stoically into space. Both images could reasonably be captioned with these lines from ‘Aubade:’ ‘The sure extinction that we travel to/ And shall be lost in always.’ Collectively, the photographs in The Importance of Elsewhere provide numerous visual insights into Larkin’s life and poetry.

http://www.thelondonmagazine.org/

Terry Kelly

The London Magazine

December/January 2016

Memorability is one of the most striking features of Philip Larkin’s poetry. Certain lines and images from his work remain indelibly fixed in the minds of his many admirers. From the philosophically elevated - ‘What will survive of us is love’ - to the starkly demotic - ‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad’ - Larkin’s lines are permanently lodged in our imaginative memories. As the critic Ian Hamilton stated, ‘More often than any other English poet since the war, Larkin gave us lines that it is unlikely we’ll be able to forget.’ But apart from creating verse which repeatedly passes the quotability test, Larkin was also a lifelong keen amateur photographer, lavishing on his pictures the same kind of care and attention and eye for detail he brought to his verse. And these photographic qualities helped nur- ture his poetry, adding to its often picture-sharp memorability. While he was certainly no Cartier-Bresson or Bill Brandt, Larkin’s skilful pictures undoubtedly influenced his poetry, while also providing insights into his literary imagination. Plus, the numerous formal and informal pictures he took of family members, including his long-suffering mother, Eva, lovers Monica Jones, Maeve Brennan and Betty Mackereth, as well as university colleagues and the various places where he lived and worked, represent an unrivalled visual commentary on his life. All these qualities make Richard Bradford’s book a welcome addition to the Larkin canon. Although some may accuse accuse Bradford of barrel-scraping or bloating the already considerable posthumous Larkin estate, devotees of the poet will welcome this visual treasure trove from one of the twentieth century’s greatest lyric poets. Many of the dozens of photographs in the volume, drawn from the 5,000-strong Larkin photographic archive at Hull History Centre, will be new to even his most dedicated readers, making the book essential reading for his huge readership.

In a perceptive foreword, Mark Haworth-Booth, former curator of photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum, reveals that Larkin’s father, Sydney, gave his son his first camera, a Houghton-Butcher Ensign Carbine no. 5, now preserved at Hull History Centre. A diligent student of photography, Larkin kept up to date with the art form through magazines such as Lilliput and Picture Post. (While Librarian at the University of Hull, Larkin acquired a complete run of Picture Post, from 1938 to 1957). Although many of Larkin’s photographs are of domestic scenes, there was a wider, documentary aspect to his work with a camera, which in turn inspired his poetry. Haworth-Booth: ‘Larkin used photography to sharpen his connection with the broader social landscape towards which he was simultaneously reaching in his poems’. This fruitful chemistry between the visual and poetic is evident in the memorable exterior images outside the train carriage immortalised in ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ or the panoramic sweep of a poem like ‘Here’: ‘Swerving east, from rich industrial shadows/ And traffic all night north...’ A photograph of Rooney’s the jewellers in Dublin was taken during Larkin’s creatively productive sojourn in Belfast, which resulted in a poem which gives Bradford’s book its title. Haworth-Booth speculates that Larkin’s evocative street study was the inspiration for the much later poem, ‘Dublinesque,’ about an Irish funeral. There are even more direct visual-poetic links between snaps Larkin took at the Bellingham Country Show in Northumberland and ‘Show Saturday,’ a poem added very late in the day to High Windows (1974), the poet’s final collection. A Larkin picture of wrestlers grappling with one another was later transmuted into an image of amateur sportsmen involved in ‘long immobile strainings that end in unbalance.’

The book is divided into two sections, the first providing a biographical backdrop to Larkin’s photographs ‘Before Hull’ - including family, friends, early girlfriend Ruth Bowman, Oxford, Wellington, Leicester, Belfast, Monica Jones - and the second looking at ‘Hull and Elsewhere,’ featuring Maeve Brennan, poets, Hull scenes and holiday snaps. As the book reveals, Larkin often cropped his photographs with great skill to emphasise an aspect of a scene, or, as in the case of his famous self-portrait at the border town Coldstream, to underline the essential Englishness of his subject matter. Significantly, given the influence he had on the poet’s life, ‘Before Hull’ opens with one of his earliest photographs, of his father, Sydney, taken at 1 Manor Road, Coventry, when Larkin was just eleven. In a nice, ironic twist, Sydney is captured simultaneously taking a photograph of his young son. The book features several pictures of Sydney in domestic or relaxed outdoor contexts, softening the rather severe image we have of Larkin’s father. Early images also feature the Larkin family holidaying in Germa- ny and Folkestone in the 1930s. There are even several pictures of Kitty, Larkin’s rather shadowy sister.

Bradford thinks Larkin ‘tried desperately to reinvent himself’ at Oxford, turning into the kind of louche aesthete we find in Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall. The poet also set about photographing his talented contemporar- ies at wartime Oxford, lifelong friend Kingsley Amis included. After failing conscription because of his poor eyesight, Bradford believes Larkin assumed ‘the role of visual elegist, roaming through St John’s with a camera he had brought from Coventry, once his father’s, and photographing friends and contemporaries, some of whom he hardly knew.’ According to Bradford, the captions Larkin composed for pictures of these wartime friends ‘invite comparison with a ‘lost in action’ reference in dispatches, or even a gravestone.’ The intense relationship which developed at Oxford between Larkin and Kingsley Amis has already been explored by Brad- ford in a previous book and he suggests in The Importance of Elsewhere that Amis ‘had effectively taken control of Larkin’ at this stage in their lives. The book features numerous pictures of Amis and his girlfriend and future wife, Hilly, who is captured in voluptuous, seductive poses by Larkin. The portraits in the new book are testament to the flirtatious relationship between Larkin and Hilly. (Larkin would later take similar pictures of his on-off girlfriend, Patsy Strang.)

Memorability is one of the most striking features of Philip Larkin’s poetry. Certain lines and images from his work remain indelibly fixed in the minds of his many admirers. From the philosophically elevated - ‘What will survive of us is love’ - to the starkly demotic - ‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad’ - Larkin’s lines are permanently lodged in our imaginative memories. As the critic Ian Hamilton stated, ‘More often than any other English poet since the war, Larkin gave us lines that it is unlikely we’ll be able to forget.’ But apart from creating verse which repeatedly passes the quotability test, Larkin was also a lifelong keen amateur photographer, lavishing on his pictures the same kind of care and attention and eye for detail he brought to his verse. And these photographic qualities helped nur- ture his poetry, adding to its often picture-sharp memorability. While he was certainly no Cartier-Bresson or Bill Brandt, Larkin’s skilful pictures undoubtedly influenced his poetry, while also providing insights into his literary imagination. Plus, the numerous formal and informal pictures he took of family members, including his long-suffering mother, Eva, lovers Monica Jones, Maeve Brennan and Betty Mackereth, as well as university colleagues and the various places where he lived and worked, represent an unrivalled visual commentary on his life. All these qualities make Richard Bradford’s book a welcome addition to the Larkin canon. Although some may accuse accuse Bradford of barrel-scraping or bloating the already considerable posthumous Larkin estate, devotees of the poet will welcome this visual treasure trove from one of the twentieth century’s greatest lyric poets. Many of the dozens of photographs in the volume, drawn from the 5,000-strong Larkin photographic archive at Hull History Centre, will be new to even his most dedicated readers, making the book essential reading for his huge readership.

In a perceptive foreword, Mark Haworth-Booth, former curator of photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum, reveals that Larkin’s father, Sydney, gave his son his first camera, a Houghton-Butcher Ensign Carbine no. 5, now preserved at Hull History Centre. A diligent student of photography, Larkin kept up to date with the art form through magazines such as Lilliput and Picture Post. (While Librarian at the University of Hull, Larkin acquired a complete run of Picture Post, from 1938 to 1957). Although many of Larkin’s photographs are of domestic scenes, there was a wider, documentary aspect to his work with a camera, which in turn inspired his poetry. Haworth-Booth: ‘Larkin used photography to sharpen his connection with the broader social landscape towards which he was simultaneously reaching in his poems’. This fruitful chemistry between the visual and poetic is evident in the memorable exterior images outside the train carriage immortalised in ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ or the panoramic sweep of a poem like ‘Here’: ‘Swerving east, from rich industrial shadows/ And traffic all night north...’ A photograph of Rooney’s the jewellers in Dublin was taken during Larkin’s creatively productive sojourn in Belfast, which resulted in a poem which gives Bradford’s book its title. Haworth-Booth speculates that Larkin’s evocative street study was the inspiration for the much later poem, ‘Dublinesque,’ about an Irish funeral. There are even more direct visual-poetic links between snaps Larkin took at the Bellingham Country Show in Northumberland and ‘Show Saturday,’ a poem added very late in the day to High Windows (1974), the poet’s final collection. A Larkin picture of wrestlers grappling with one another was later transmuted into an image of amateur sportsmen involved in ‘long immobile strainings that end in unbalance.’

The book is divided into two sections, the first providing a biographical backdrop to Larkin’s photographs ‘Before Hull’ - including family, friends, early girlfriend Ruth Bowman, Oxford, Wellington, Leicester, Belfast, Monica Jones - and the second looking at ‘Hull and Elsewhere,’ featuring Maeve Brennan, poets, Hull scenes and holiday snaps. As the book reveals, Larkin often cropped his photographs with great skill to emphasise an aspect of a scene, or, as in the case of his famous self-portrait at the border town Coldstream, to underline the essential Englishness of his subject matter. Significantly, given the influence he had on the poet’s life, ‘Before Hull’ opens with one of his earliest photographs, of his father, Sydney, taken at 1 Manor Road, Coventry, when Larkin was just eleven. In a nice, ironic twist, Sydney is captured simultaneously taking a photograph of his young son. The book features several pictures of Sydney in domestic or relaxed outdoor contexts, softening the rather severe image we have of Larkin’s father. Early images also feature the Larkin family holidaying in Germa- ny and Folkestone in the 1930s. There are even several pictures of Kitty, Larkin’s rather shadowy sister.

Bradford thinks Larkin ‘tried desperately to reinvent himself’ at Oxford, turning into the kind of louche aesthete we find in Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall. The poet also set about photographing his talented contemporar- ies at wartime Oxford, lifelong friend Kingsley Amis included. After failing conscription because of his poor eyesight, Bradford believes Larkin assumed ‘the role of visual elegist, roaming through St John’s with a camera he had brought from Coventry, once his father’s, and photographing friends and contemporaries, some of whom he hardly knew.’ According to Bradford, the captions Larkin composed for pictures of these wartime friends ‘invite comparison with a ‘lost in action’ reference in dispatches, or even a gravestone.’ The intense relationship which developed at Oxford between Larkin and Kingsley Amis has already been explored by Brad- ford in a previous book and he suggests in The Importance of Elsewhere that Amis ‘had effectively taken control of Larkin’ at this stage in their lives. The book features numerous pictures of Amis and his girlfriend and future wife, Hilly, who is captured in voluptuous, seductive poses by Larkin. The portraits in the new book are testament to the flirtatious relationship between Larkin and Hilly. (Larkin would later take similar pictures of his on-off girlfriend, Patsy Strang.)

Larkin’s friend and early publisher Jean Hartley always maintained that it was Maeve Brennan, not Monica Jones, who was the great love of Larkin’s life. Certainly, the photographs the poet took of both women are a study in contrasts. A typical early portrait of Monica in the book shows the flamboyant university lecturer in her office at Leicester in 1947; arms folded assertively, a cigarette between her fingers, while directing her trademark unflinching stare at the camera. At least early on in their relationship, Larkin would carefully construct his portraits of Monica, including a highly stylised photograph in the garden of her Leicester flat. The picture prompted Larkin to reveal, in a letter to his lover in January 1951, that the dress she wore ‘arouses the worst in me’. But it’s also fair to say that as Monica aged and gained weight, Larkin’s photographs of her became more casual and less erotically charged. (A quotation from his poem, ‘Lines on a Young Lady’s Photograph Album,’ is relevant here: ‘But o, photography! as no art is,/Faithful and disappointing!’) In stark contrast, Larkin’s pictures of Maeve are far less obviously sexual, presenting his later love interest as pure, like an idealised, muse-like figure. Although the pictures are warm and intimate, they also capture something of the personal and moral reticence of the devout Roman Catholic. For example, Larkin photographed Maeve staring through long grass in 1961, suggesting her reserved, unobtainable quality. For Bradford, Maeve was ‘plain, bright enough but unsophisticated,’ speculating the poet was attracted to his library colleague precisely because of her objections to sex outside marriage. Contrasting the two women in Larkin’s life, Bradford believes that ‘Monica challenged him, intellectually and emotionally, while Maeve mirrored the parts of his temperament that he had largely concealed or subdued, particularly his crippling anxiety, shyness and insularity.’ The author believes Maeve is often photographed ‘in an Edwardian time warp,’ adding, rather cruelly, that ‘Larkin took care to capture a physiognomy that was not classically handsome, one which combined the combative features of maleness with a weary acceptance of middle age’ In fact, some of the pictures of Maeve in the book contradict this blunt estimate. In most of the photographs featured, Maeve is smiling naturally and unaffectedly for the camera, for example, in a hotel in Hornsea or in the countryside. While Bradford calls Maeve ‘happily uncultured’ in such pictures, there is an undeniable emotional warmth in the portraits, as though Larkin is also smiling behind the camera. But it’s difficult to find a photograph of a smiling Monica.

Larkin’s photographic self-portraits possess a haunted, Hopperesque quality. Never at ease with his own appearance, this physical disquiet is reflected in his pictures. But he persisted in taking photographs of himself with a timer, suggesting either an abiding need for self analysis, a desire to sharpen his camera skills or simple egotism. In one of his earliest self-portraits, taken in his room at St John’s, Oxford, Larkin is reflected in a mirror, the young poet looking suitably introspective. When not taking bleak, existential pictures of his empty bedrooms in Belfast or Pearson Park, Hull - which are almost visual evocations of the poem ‘Mr Bleaney’ - a typically glum Larkin is pictured holding a wicker rabbit, in a picture sequence taken by Monica in 1962. But good as some of Larkin’s interior shots and portraits are, his pictures of street scenes are some of the strong- est images in the book. These include an evocative study - inscribed ‘To the Match’- taken in 1949, showing Leicester City fans on their way to the Filbert Street ground, wrapped in a ghostly half-light. Larkin’s time in Belfast proved extremely fruitful for both his poetry and photography. There are several pictures of mass marches through the streets of Belfast and of the Walls of Derry. A return visit to Ireland by Larkin in 1969 produced more striking images, including a colour shot of Belfast before the 12 July festivities. Also featured are some of the idyllic rural scenes Larkin photographed in the East Riding countryside, including Laxton, Yokefleet, Kilpin and Faxfleet, the images providing a lush, visual complement to lyrically upbeat poems such as ‘Cut Grass’ and ‘The Trees.’

But there’s also a sense that as Larkin’s poetic muse abandoned him, his interest in photography also waned. Some of the final pictures in Brad- ford’s book have a casual, almost throwaway quality. And the starkness of Larkin’s later verse, most notably the death-obsessed ‘Aubade,’ finds a visual equivalent in the book’s final, echoing images. One photograph shows the older Monica Jones, wearing a rather frumpy dress, staring blankly out of a window, while the adjacent picture captures Larkin’s mother, Eva, shortly before her death, staring stoically into space. Both images could reasonably be captioned with these lines from ‘Aubade:’ ‘The sure extinction that we travel to/ And shall be lost in always.’ Collectively, the photographs in The Importance of Elsewhere provide numerous visual insights into Larkin’s life and poetry.

No comments:

Post a Comment