Paddy Ashdown obituary

Former leader of the Liberal Democrats who helped transform party into a British political forceStephen Bates

The Guardian

Sat 22 Dec 2018

Paddy Ashdown, who has died aged 77, was perhaps the most unlikely leader the Liberal strand of British politics has ever had. A former captain in the Royal Marines, ex-diplomat and, it was rumoured, a spy, he became the first leader of the Liberal Democrats in 1988 and led them over the next 11 years to their best electoral results at that time for three-quarters of a century. Although he never quite achieved the parliamentary breakthrough he hoped for, still less a realignment of the parties of the left in coalition with Labour, the Lib Dems became a significant and influential third force in British politics.

It was no mean achievement for a man who was regarded as uncollegiate by many of his colleagues and was a moderate speaker and poor Commons performer. What he was able to do, with hard-driving and ruthless ambition, was to turn the party from a bunch of egotistical oddballs and individualists at Westminster – in his words “a funny little herbivorous think-tank on the edges of British politics” – into a national movement that earnestly believed it could win a measure of power and convinced a swathe of the soft-left electorate that it was capable of doing so.

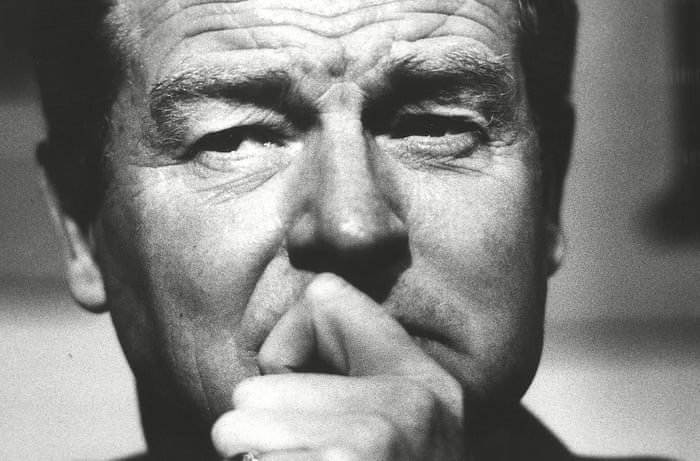

Square-jawed, eyes narrowed as if constantly scanning the horizon, resolutely refusing to confirm or deny that he knew how to kill a man with his bare hands from his days fighting communist insurgents in the jungles of Borneo with the Marines’ Special Boat Section, Ashdown looked like a leader of a more militant party than he actually led. If he was helped in the early 1990s by voters’ growing disillusionment with the Tories and initial reluctance in southern shire constituencies to trust Labour, he also had to overcome a ramshackle and near-bankrupt national party machine and often nonexistent local organisations.

Ashdown accomplished this despite coming from a non-liberal party background and not even having been a member of, or voting for, the party until he was in his mid-thirties. He had always been a Labour voter – not necessarily a career advantage in the officers’ mess or the diplomatic service – until being converted one day, he claimed, by a local Liberal canvasser who came knocking at his Somerset cottage door during the general election campaign in January 1974.

He recalled in his memoirs: “I definitely remember that he wore an orange anorak, looked unprepossessing and had a squeaky voice to match … My memory may be playing tricks when it tells me he also had sandals and a wispy beard. I told him pretty roughly that I certainly would not vote Liberal unless (which I considered highly unlikely) he could persuade me that I should. I don’t know quite what happened next. But two hours later, having discussed liberalism at length in our front room, I discovered that this was what I had really always been … Liberalism was an old coat that had been hanging in my cupboard … just waiting to be taken down and put on.” He was never able to track down this evangelist again.

Ashdown was the oldest of seven children, born in New Delhi, the son of John Ashdown, an Ulster Protestant who was an Indian army captain and his Ulster Catholic wife, Lois (nee Hudson), who had been an army nurse. The family did not return to Northern Ireland until after the end of the war, when his father invested his savings in a pig farm and then a market garden, both of which failed. Ashdown was christened Jeremy John Durham but gained his nickname, Paddy, from his Irish accent when his father managed to obtain a place for him at Bedford school, where he himself had been educated. The accent was soon lost, though the nickname never was, and there Ashdown obtained a military scholarship, which paid the school fees. He excelled at sport, but not academic study. He failed his French O-level, though later became proficient in several languages, including Mandarin, Hindi, Malay, Serbo-Croat, German and indeed French.

He joined the Royal Marines straight from school at about the time his parents decided to make a new life in Australia. Ashdown served for 12 years in the Marines and saw action as a commando in Kuwait, Borneo, Hong Kong and Northern Ireland where, in the early days of the Troubles, he was once required to arrest the Catholic civil rights activist and future fellow MP John Hume on the streets of Belfast. In interviews many years later, Ashdown insisted that had he been an Ulster Catholic he would probably have joined the IRA, or at least campaigned for civil rights himself.

His fluency in Chinese led to a posting with the diplomatic service, formally as first secretary to the UK’s mission to the United Nations in Geneva, where he was allegedly – Ashdown was coy on the matter – required to listen in on the conversations of the Chinese delegation and cultivate contacts. But he threw up his promising diplomatic career for family life in Norton-sub-Hamdon, a Somerset village near Yeovil with his wife, Jane, whom he had met at a military ball when he was 20, and their two small children, and joined the local Liberal association. He wrote in his memoirs that the decision was naive to the point of irresponsibility: “It just also happens to be the best decision I … made in my life.”

Ashdown was quickly chosen as the party’s candidate in a safe Tory seat and, with energy and dedication, set about reviving the moribund association and launching the sort of grassroots activist campaigns for which the Liberals later became famous: canvassing, issuing press releases, fundraising, and needling the complacent local Tories.

He spent time on the dole, but eventually managed to get a clerical job with the local Westland helicopter firm and later with the short-lived Morland sheepskin company. Then, when he and his wife got down to their last £150, they decided that he would give up political ambition and return to the Foreign Office if nothing came up within a month. They were saved by the unexpected arrival of a £1,000 grant from the Rowntree Trust, arranged by national Liberal friends.

Ashdown calculated that it would need three elections in his constituency to beat the Tories, but in the event it took only two. He was elected – one of five new Liberal MPs – in the Thatcher landslide election of 1983 and arrived at Westminster to find the party riven by personal rivalries and its alliance with the Social Democratic party, led by David Owen, growing increasingly fractious.

The parties’ failure to make a breakthrough in the 1987 general election led to the emergence of the Social and Liberal Democratic party – inevitably immediately dubbed “Salads” in the press. A name change resulted in the emergence of the Liberal Democrats, who absorbed most of the SDP remnant while shedding a few diehard Liberals. Following the resignation of the previous Liberal leader, David Steel, Ashdown won the support of 72% of the party faithful against 28% for his rival, Alan Beith. The membership was demoralised and the party was on the verge of bankruptcy, grateful for the new leader’s dynamism, but not instinctively sympathetic to someone who had only been a member for 14 years and an MP for five.

Ashdown struggled to make an impression in the chamber against Labour and Tory heckling and could be smug, humourless and patronising. “I am not a natural speaker,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I tend to speak too fast, my voice has a habit of rising in register when I am nervous. I have a poor sense of timing for jokes and I tend to lose all light and shade in my delivery when under pressure.”

Disaffected colleagues joked that the message on his answerphone said: “Please leave a message after the high moral tone.” Nor did he support all traditional Liberals’ articles of faith, proclaiming himself a multilateralist and an opponent of the proposed European takeover of Westland in his constituency. Colleagues complained that he did not think deeply about issues or listen to their views, but took off on high profile “listening to the people” nationwide tours instead.

As the 1992 general election approached, Ashdown sought an injunction against press revelations of an affair five years earlier with his former Commons secretary, Tricia Howard, which had been discovered by burglars who had broken into his solicitor’s office and stolen papers from a safe. News of the affair came out anyway, producing the memorable Sun headline “Paddy Pantsdown”. Far from the feared electoral disaster, the party’s standing in the polls went up. Ashdown’s marriage survived, but the hoped-for breakthrough at the election, leading to a realignment on the left, once more failed to materialise: the party gained just one seat, for a total of 20.

This was however followed by a series of sweeping byelection victories in safe Tory constituencies at Newbury, Christchurch and Eastleigh and before the 1997 election, Ashdown engaged in secret talks the Labour leader, Tony Blair, about forming a coalition. In the event, Blair won a landslide victory. Nevertheless, the Lib Dems gained nearly 18% of the vote and more than doubled their representation to 46 seats, their best result in more than 70 years.

By then Ashdown’s focus had shifted elsewhere, to the war in former Yugoslavia. He had first visited Sarajevo after the 1992 election to study what was happening as a former military man and grew increasingly passionate about the crisis and outraged at the west’s apparent indifference to the slaughter going on there. “It was a moral imperative, a terrible vision of the future … I was obsessed by the nightmare of it all,” he wrote. “There was this sense of guilt and anger.” His regular visits were fraught with danger and at Westminster he harried John Major’s government for its lack of action.

This took a more concrete form after he stood down from the Lib Dem leadership in 1999 and from the Commons at the general election two years later. Following the war in Kosovo, he was made high representative of the International Community and EU special representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina for four years from 2002. The role gave him plenipotentiary powers to sack politicians and even judges, to issue decrees and set up institutions from his office in Sarajevo, though supervised by the allied powers. In 2007 the British and US governments offered him a similar role in Afghanistan, but he was rejected by the Afghan president, Hamid Karzai.

Instead Ashdown remained active in Lib Dem politics. He was made a life peer in 2001 and turned to writing books: two volumes of diaries, his memoirs, A Fortunate Life, and well-received histories of incidents in the second world war: the Royal Marines’ disastrous attempt to destroy German shipping at Bordeaux in 1942 and the French resistance’s battle on the Vercours plateau in 1944. He became president of Unicef UK in 2009.

In 2015 he supervised the Lib Dems’ disastrous general election campaign, following their period of coalition with the Tories under Nick Clegg’s leadership, which saw them lose 49 of their 57 seats. He revealed, in November of this year, that he had been diagnosed with bladder cancer. “I have known for about three weeks that I am suffering from a cancer of the bladder,” he told Somerset Live. “I’m being effectively and wonderfully looked after by everyone at Yeovil hospital.”

He had told the Observer in 2013 that he was not sad never to have been prime minister: “Not really, not any longer. Am I proud to have been the founder leader of a party that survived against the odds and has done bloody well in the first coalition government at an exceedingly difficult time? Yeah, I burn with pride about that.”

He is survived by Jane and their daughter, Kate and son, Simon.

• Jeremy John Durham (Paddy) Ashdown, Lord Ashdown of Norton-sub-Hamdon, born 27 February 1941; died 22 December 2018.

Sat 22 Dec 2018

Paddy Ashdown, who has died aged 77, was perhaps the most unlikely leader the Liberal strand of British politics has ever had. A former captain in the Royal Marines, ex-diplomat and, it was rumoured, a spy, he became the first leader of the Liberal Democrats in 1988 and led them over the next 11 years to their best electoral results at that time for three-quarters of a century. Although he never quite achieved the parliamentary breakthrough he hoped for, still less a realignment of the parties of the left in coalition with Labour, the Lib Dems became a significant and influential third force in British politics.

It was no mean achievement for a man who was regarded as uncollegiate by many of his colleagues and was a moderate speaker and poor Commons performer. What he was able to do, with hard-driving and ruthless ambition, was to turn the party from a bunch of egotistical oddballs and individualists at Westminster – in his words “a funny little herbivorous think-tank on the edges of British politics” – into a national movement that earnestly believed it could win a measure of power and convinced a swathe of the soft-left electorate that it was capable of doing so.

Square-jawed, eyes narrowed as if constantly scanning the horizon, resolutely refusing to confirm or deny that he knew how to kill a man with his bare hands from his days fighting communist insurgents in the jungles of Borneo with the Marines’ Special Boat Section, Ashdown looked like a leader of a more militant party than he actually led. If he was helped in the early 1990s by voters’ growing disillusionment with the Tories and initial reluctance in southern shire constituencies to trust Labour, he also had to overcome a ramshackle and near-bankrupt national party machine and often nonexistent local organisations.

Ashdown accomplished this despite coming from a non-liberal party background and not even having been a member of, or voting for, the party until he was in his mid-thirties. He had always been a Labour voter – not necessarily a career advantage in the officers’ mess or the diplomatic service – until being converted one day, he claimed, by a local Liberal canvasser who came knocking at his Somerset cottage door during the general election campaign in January 1974.

He recalled in his memoirs: “I definitely remember that he wore an orange anorak, looked unprepossessing and had a squeaky voice to match … My memory may be playing tricks when it tells me he also had sandals and a wispy beard. I told him pretty roughly that I certainly would not vote Liberal unless (which I considered highly unlikely) he could persuade me that I should. I don’t know quite what happened next. But two hours later, having discussed liberalism at length in our front room, I discovered that this was what I had really always been … Liberalism was an old coat that had been hanging in my cupboard … just waiting to be taken down and put on.” He was never able to track down this evangelist again.

Ashdown was the oldest of seven children, born in New Delhi, the son of John Ashdown, an Ulster Protestant who was an Indian army captain and his Ulster Catholic wife, Lois (nee Hudson), who had been an army nurse. The family did not return to Northern Ireland until after the end of the war, when his father invested his savings in a pig farm and then a market garden, both of which failed. Ashdown was christened Jeremy John Durham but gained his nickname, Paddy, from his Irish accent when his father managed to obtain a place for him at Bedford school, where he himself had been educated. The accent was soon lost, though the nickname never was, and there Ashdown obtained a military scholarship, which paid the school fees. He excelled at sport, but not academic study. He failed his French O-level, though later became proficient in several languages, including Mandarin, Hindi, Malay, Serbo-Croat, German and indeed French.

He joined the Royal Marines straight from school at about the time his parents decided to make a new life in Australia. Ashdown served for 12 years in the Marines and saw action as a commando in Kuwait, Borneo, Hong Kong and Northern Ireland where, in the early days of the Troubles, he was once required to arrest the Catholic civil rights activist and future fellow MP John Hume on the streets of Belfast. In interviews many years later, Ashdown insisted that had he been an Ulster Catholic he would probably have joined the IRA, or at least campaigned for civil rights himself.

His fluency in Chinese led to a posting with the diplomatic service, formally as first secretary to the UK’s mission to the United Nations in Geneva, where he was allegedly – Ashdown was coy on the matter – required to listen in on the conversations of the Chinese delegation and cultivate contacts. But he threw up his promising diplomatic career for family life in Norton-sub-Hamdon, a Somerset village near Yeovil with his wife, Jane, whom he had met at a military ball when he was 20, and their two small children, and joined the local Liberal association. He wrote in his memoirs that the decision was naive to the point of irresponsibility: “It just also happens to be the best decision I … made in my life.”

Ashdown was quickly chosen as the party’s candidate in a safe Tory seat and, with energy and dedication, set about reviving the moribund association and launching the sort of grassroots activist campaigns for which the Liberals later became famous: canvassing, issuing press releases, fundraising, and needling the complacent local Tories.

He spent time on the dole, but eventually managed to get a clerical job with the local Westland helicopter firm and later with the short-lived Morland sheepskin company. Then, when he and his wife got down to their last £150, they decided that he would give up political ambition and return to the Foreign Office if nothing came up within a month. They were saved by the unexpected arrival of a £1,000 grant from the Rowntree Trust, arranged by national Liberal friends.

Ashdown calculated that it would need three elections in his constituency to beat the Tories, but in the event it took only two. He was elected – one of five new Liberal MPs – in the Thatcher landslide election of 1983 and arrived at Westminster to find the party riven by personal rivalries and its alliance with the Social Democratic party, led by David Owen, growing increasingly fractious.

The parties’ failure to make a breakthrough in the 1987 general election led to the emergence of the Social and Liberal Democratic party – inevitably immediately dubbed “Salads” in the press. A name change resulted in the emergence of the Liberal Democrats, who absorbed most of the SDP remnant while shedding a few diehard Liberals. Following the resignation of the previous Liberal leader, David Steel, Ashdown won the support of 72% of the party faithful against 28% for his rival, Alan Beith. The membership was demoralised and the party was on the verge of bankruptcy, grateful for the new leader’s dynamism, but not instinctively sympathetic to someone who had only been a member for 14 years and an MP for five.

Ashdown struggled to make an impression in the chamber against Labour and Tory heckling and could be smug, humourless and patronising. “I am not a natural speaker,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I tend to speak too fast, my voice has a habit of rising in register when I am nervous. I have a poor sense of timing for jokes and I tend to lose all light and shade in my delivery when under pressure.”

Disaffected colleagues joked that the message on his answerphone said: “Please leave a message after the high moral tone.” Nor did he support all traditional Liberals’ articles of faith, proclaiming himself a multilateralist and an opponent of the proposed European takeover of Westland in his constituency. Colleagues complained that he did not think deeply about issues or listen to their views, but took off on high profile “listening to the people” nationwide tours instead.

As the 1992 general election approached, Ashdown sought an injunction against press revelations of an affair five years earlier with his former Commons secretary, Tricia Howard, which had been discovered by burglars who had broken into his solicitor’s office and stolen papers from a safe. News of the affair came out anyway, producing the memorable Sun headline “Paddy Pantsdown”. Far from the feared electoral disaster, the party’s standing in the polls went up. Ashdown’s marriage survived, but the hoped-for breakthrough at the election, leading to a realignment on the left, once more failed to materialise: the party gained just one seat, for a total of 20.

This was however followed by a series of sweeping byelection victories in safe Tory constituencies at Newbury, Christchurch and Eastleigh and before the 1997 election, Ashdown engaged in secret talks the Labour leader, Tony Blair, about forming a coalition. In the event, Blair won a landslide victory. Nevertheless, the Lib Dems gained nearly 18% of the vote and more than doubled their representation to 46 seats, their best result in more than 70 years.

By then Ashdown’s focus had shifted elsewhere, to the war in former Yugoslavia. He had first visited Sarajevo after the 1992 election to study what was happening as a former military man and grew increasingly passionate about the crisis and outraged at the west’s apparent indifference to the slaughter going on there. “It was a moral imperative, a terrible vision of the future … I was obsessed by the nightmare of it all,” he wrote. “There was this sense of guilt and anger.” His regular visits were fraught with danger and at Westminster he harried John Major’s government for its lack of action.

This took a more concrete form after he stood down from the Lib Dem leadership in 1999 and from the Commons at the general election two years later. Following the war in Kosovo, he was made high representative of the International Community and EU special representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina for four years from 2002. The role gave him plenipotentiary powers to sack politicians and even judges, to issue decrees and set up institutions from his office in Sarajevo, though supervised by the allied powers. In 2007 the British and US governments offered him a similar role in Afghanistan, but he was rejected by the Afghan president, Hamid Karzai.

Instead Ashdown remained active in Lib Dem politics. He was made a life peer in 2001 and turned to writing books: two volumes of diaries, his memoirs, A Fortunate Life, and well-received histories of incidents in the second world war: the Royal Marines’ disastrous attempt to destroy German shipping at Bordeaux in 1942 and the French resistance’s battle on the Vercours plateau in 1944. He became president of Unicef UK in 2009.

In 2015 he supervised the Lib Dems’ disastrous general election campaign, following their period of coalition with the Tories under Nick Clegg’s leadership, which saw them lose 49 of their 57 seats. He revealed, in November of this year, that he had been diagnosed with bladder cancer. “I have known for about three weeks that I am suffering from a cancer of the bladder,” he told Somerset Live. “I’m being effectively and wonderfully looked after by everyone at Yeovil hospital.”

He had told the Observer in 2013 that he was not sad never to have been prime minister: “Not really, not any longer. Am I proud to have been the founder leader of a party that survived against the odds and has done bloody well in the first coalition government at an exceedingly difficult time? Yeah, I burn with pride about that.”

He is survived by Jane and their daughter, Kate and son, Simon.

• Jeremy John Durham (Paddy) Ashdown, Lord Ashdown of Norton-sub-Hamdon, born 27 February 1941; died 22 December 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment