Switch House, Tate Modern, London

From the tears of Man Ray to the Paris of Robert Frank and the manspread of Salvador Dali, this astounding collection is a history of modernist photography

Adrian Searle

The Guardian

Tuesday 8 November 2016

Sir Elton John’s image, his glasses askew and playing up for the camera in Irving Penn’s 1997 portrait, greets visitors to The Radical Eye. It is an endearing gag, leaving one unprepared for an exhibition as serious as it is surprising, and which could serve as a short course in the development of photography from around 1910 to 1950. The Sir Elton John collection currently contains more than 8,000 works, and even though there are fewer than a couple of hundred here, what a selection it is.

Nusch by Man Ray, 1935

Tate only began to collect photography seriously and systematically in 2009 – late in the game, they could never hope to afford works of this range and quality. This show marks the beginning of a long-term collaboration between the institution and Elton John and David Furnish, who have agreed to give works to the nation. Theirs is a collection anyone would give their eye-teeth for.

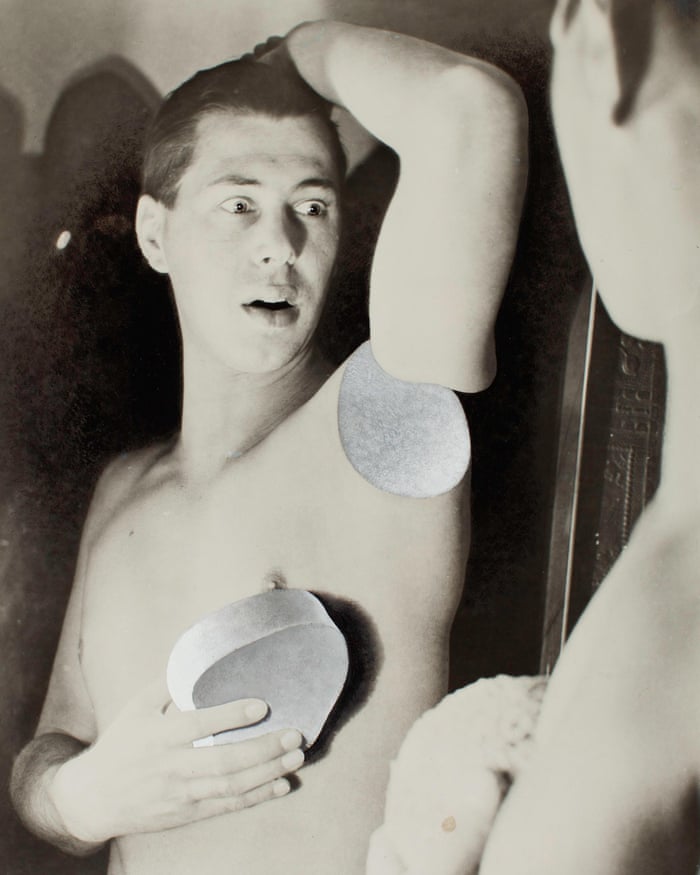

Self-Portrait by Herbert Bayer, 1932

It’s a foundational body of work, with as many surprises as there are photographs that forever reappear in anthologies and exhibitions. From Bauhaus abstraction to 1930s social documentary, via the staged and the casual, studio portraits and street photography, surrealism and still life, this is no idiot rich guy collection of trophy art. Sir Elton says he has never bought a work for profit. He has educated himself as he has gone on, beginning to collect photographs after a period in rehab for alcohol addiction in the late 80s. The collection now has a director, a curator (a former gallerist from Atlanta, where Elton has a home), and doubtless conservators to look after it.

Glass Tears by Man Ray, 1932

Tuesday 8 November 2016

Sir Elton John’s image, his glasses askew and playing up for the camera in Irving Penn’s 1997 portrait, greets visitors to The Radical Eye. It is an endearing gag, leaving one unprepared for an exhibition as serious as it is surprising, and which could serve as a short course in the development of photography from around 1910 to 1950. The Sir Elton John collection currently contains more than 8,000 works, and even though there are fewer than a couple of hundred here, what a selection it is.

Nusch by Man Ray, 1935

Tate only began to collect photography seriously and systematically in 2009 – late in the game, they could never hope to afford works of this range and quality. This show marks the beginning of a long-term collaboration between the institution and Elton John and David Furnish, who have agreed to give works to the nation. Theirs is a collection anyone would give their eye-teeth for.

Self-Portrait by Herbert Bayer, 1932

It’s a foundational body of work, with as many surprises as there are photographs that forever reappear in anthologies and exhibitions. From Bauhaus abstraction to 1930s social documentary, via the staged and the casual, studio portraits and street photography, surrealism and still life, this is no idiot rich guy collection of trophy art. Sir Elton says he has never bought a work for profit. He has educated himself as he has gone on, beginning to collect photographs after a period in rehab for alcohol addiction in the late 80s. The collection now has a director, a curator (a former gallerist from Atlanta, where Elton has a home), and doubtless conservators to look after it.

Glass Tears by Man Ray, 1932

What he doesn’t have an eye for is picture frames, which are often intrusive and over-elaborate; all that gold and distressed silver gilding, all those deluxe mats and rebates. After a while, I stopped noticing and the images themselves carried me away. It is evident that Elton appreciates photographs not just as images, but as objects, from the postage stamp-sized André Kertész 1917 Underwater Swimmer, Esztergom, Hungary, which the collector regards as the most important photograph in his collection, to Man Ray’s 1932 Larmes or Glass Tears, bought for a record sum at auction in 1993, in which a woman’s carefully made-up face has glass beads stuck to her cheeks, like a modern eroticised saint. Elton already owned a modern copy of Kertész’s Swimmer, with its refracted body and veins of light, but later bought the photographer’s original print, which bears the pencil marks where he cropped the image. A little grey thing, all its detail and tonalities leap out when you get up close.

Underwater Swimmer, Esztergom, Hungary by André Kertész, 1917

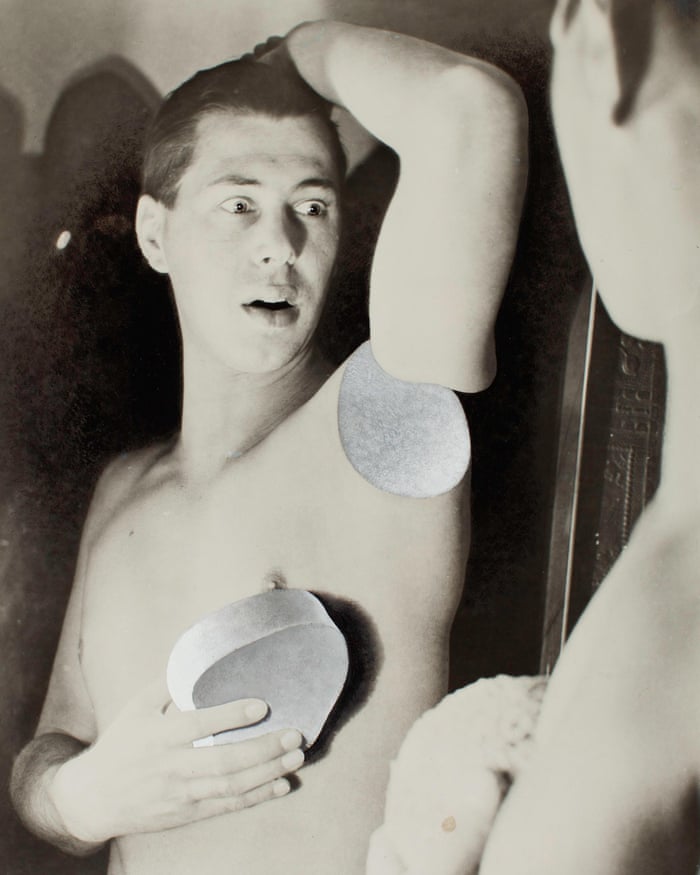

The quality of some of the prints here, let alone the images, is astounding – Edward Steichen’s portrait of silent movie star Gloria Swanson, peering out at us from behind a black, flower-decorated veil, looks almost embossed with light and shade, while László Moholy-Nagy’s 1928 vertical view down into a snowbound courtyard beneath the Berlin Radio Tower (not printed until the 1940s) has the subtlest tonalities. Werner Mantz’s 1928 view down an empty stairwell is as vertiginous as the century. Its plainness is terrifying.

View from the Berlin Radio Tower in Winter by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, 1928

One of Robert Frank’s 1949 Paris photos, looking across the sandy walk near the Place de la Concorde, is the best print of this shot that I have ever seen – every small gradation is there. Instead of a picture of a couple taking a selfie, I’m suddenly alert to the emptiness in the shot, the shadow on a bit of gravel, the foreground sweeping away, bright with light on a misty day. I could go on and on. There’s so much here.

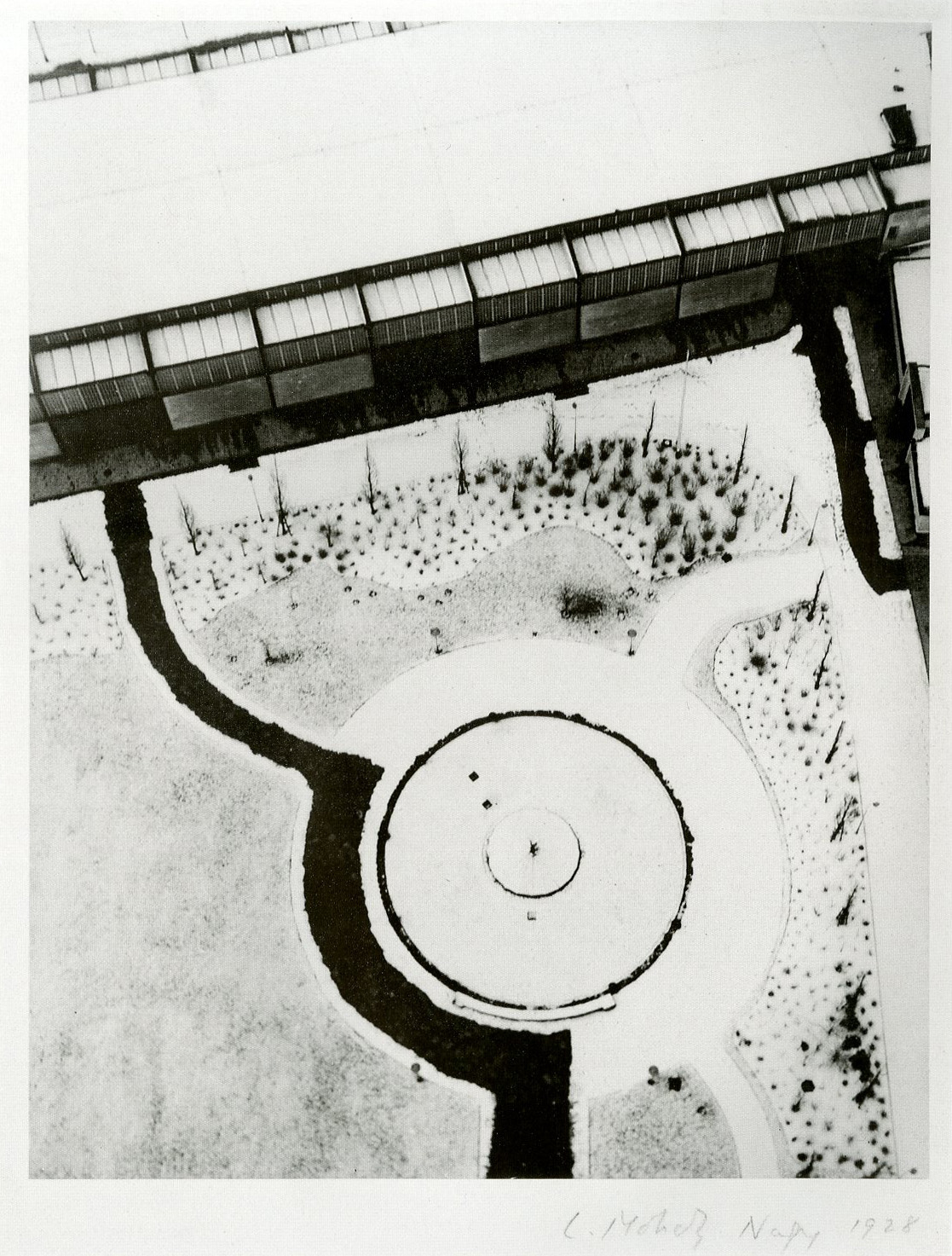

Salvador Dali in New York by Irving Penn, 1947

Elton clearly loves a portrait. Penn’s 1948 series in which Duke Ellington, Noel Coward, Joe Louis, Salvador Dalí and others pose in the tight corner between two angled walls are opportunities for their subjects to perform for the camera. Dalí manspreads aggressively; Coward poses as though he were determined to remain insouciant as the walls close in, as if he were a bookmark between the pages. There are theatrical portraits with pensive actors toying with masks; there’s beefcake, including two half-dressed men together in a pre-war Paris gay club by Brassaï. Later we come to the accusatory silent gazes of Evans’s dirt-poor whites in Alabama, and Dorothea Lange’s breadlines and homeless wandering boys, who still have pride if not much hope. Man Ray’s portraits of famous artists – Derain, Matisse, Yves Tanguy (which the collector refers to as Phil Collins) – take up one section of the show.

Christ or Chaos by Walker Evans, 1946

On the way there are photograms and shirt collars, Mondrian’s pipe in an ashtray, Herbert Bayer’s boules in the sand and Josef Sudek’s rows of teacups. Some things are easy to miss in the long runs of images: Albert Renger-Patzsch’s tremendous Mountain Forest in Winter; Diane Arbus’s early Room With Lamp and Light Fixture, New York City.

Gas Tanks by Imogen Cunningham, 1927

Imogen Cunningham’s 1927 Gas Tanks hangs next to Jaromir Funke’s 1923 Photographic Construction, pitching a staged, tabletop still life next to huge industrial cylinders and gas-holders under the sky. Funke’s staged, artificially-lit still life appears to depict a vast abstracted landscape, while Cunningham’s gas tanks look like a closeup, as near and quotidian as a plate of Cézanne’s apples. Such juxtapositions really count. I’ll have to go back. I had no idea The Radical Eye would be so impressive. It makes you want to root around the rest of what Sir Elton owns – who knows what’s in there.

The Radical Eye is at Switch House, Tate Modern, London, 10 November-7 May.

No comments:

Post a Comment