So why does it make us laugh?

Shon Arieh-Lerer

”If you are in a sexy mood the night you read [my autobiography], it may stimulate you beyond recognition and rekindle memories that you haven’t recalled in years.”

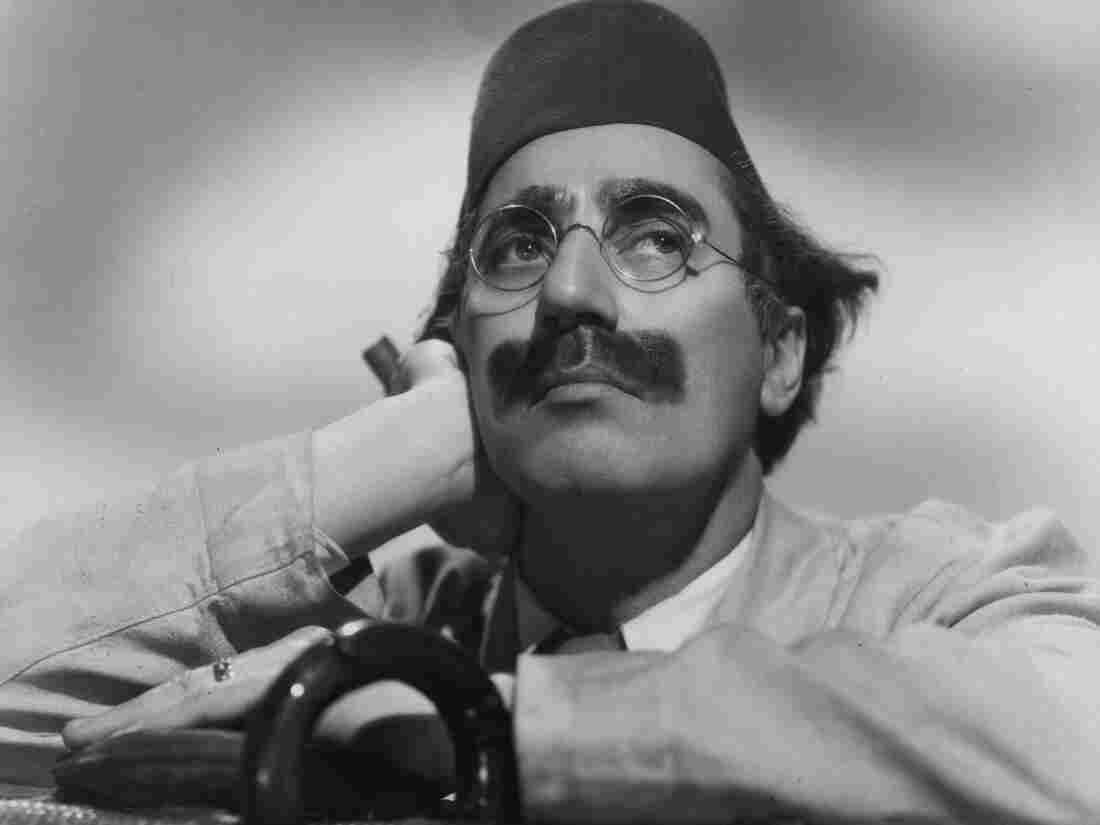

This sentence was written in a personal letter by Groucho Marx to his frenemy, T.S. Eliot. Groucho had dropped out of elementary school, and for the rest of his life strove to prove himself a man of letters, as well as to discredit men of letters. In both his private and public humor he relied heavily on words, yet had a knack for exposing all words as ultimately contentless. Hence his desire to have Eliot read his autobiography—thereby legitimizing it—as well as his need to deflate the great poet into an impotent man with a “sexy mood,” but no recent sexual activity.

This account of Groucho’s correspondence with Eliot is among a number of revealing scenes in Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, and as the book is a critical biography, all such scenes are in service of a literary and philosophical analysis. This is what explicitly distinguishes this book from previous Marx biographies: In Siegel’s hands, the details of Groucho’s life are less interesting than the broader literary argument that they illustrate, which Groucho would have found both deeply validating and kind of annoying. To any literarily or philosophically inclined Groucho fan, however, the book is a luminous delight.

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence is in itself a kind of funny title. Not only does it feature the scientifically funny hard-C sound, but it’s also deeply pretentious. And pretentiousness, being a form of ego-inflation, is among comedy’s most reliable targets. So it’s a self-defeating title: a reader who understands the comedy of existence would also make fun of the phrase “the comedy of existence.” Inspired paradox is at the heart of Siegel’s understanding of Groucho. He argues that the Marx Brothers’ comedy seeks to destroy everything, including the possibility of comedy itself. “Well, all the jokes can’t be good,” says Groucho in Animal Crackers. “You’ve got to expect that once in a while.”

”If you are in a sexy mood the night you read [my autobiography], it may stimulate you beyond recognition and rekindle memories that you haven’t recalled in years.”

This sentence was written in a personal letter by Groucho Marx to his frenemy, T.S. Eliot. Groucho had dropped out of elementary school, and for the rest of his life strove to prove himself a man of letters, as well as to discredit men of letters. In both his private and public humor he relied heavily on words, yet had a knack for exposing all words as ultimately contentless. Hence his desire to have Eliot read his autobiography—thereby legitimizing it—as well as his need to deflate the great poet into an impotent man with a “sexy mood,” but no recent sexual activity.

This account of Groucho’s correspondence with Eliot is among a number of revealing scenes in Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, and as the book is a critical biography, all such scenes are in service of a literary and philosophical analysis. This is what explicitly distinguishes this book from previous Marx biographies: In Siegel’s hands, the details of Groucho’s life are less interesting than the broader literary argument that they illustrate, which Groucho would have found both deeply validating and kind of annoying. To any literarily or philosophically inclined Groucho fan, however, the book is a luminous delight.

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence is in itself a kind of funny title. Not only does it feature the scientifically funny hard-C sound, but it’s also deeply pretentious. And pretentiousness, being a form of ego-inflation, is among comedy’s most reliable targets. So it’s a self-defeating title: a reader who understands the comedy of existence would also make fun of the phrase “the comedy of existence.” Inspired paradox is at the heart of Siegel’s understanding of Groucho. He argues that the Marx Brothers’ comedy seeks to destroy everything, including the possibility of comedy itself. “Well, all the jokes can’t be good,” says Groucho in Animal Crackers. “You’ve got to expect that once in a while.”

Siegel observes that the Brothers routinely let loose streams of cascading puns, malapropisms, word associations, and seemingly pointless slapstick that are perplexingly bad and often aggressively anti-comedic, but taken collectively become overwhelming, and thereby hilarious. In the words of the 1930s film critic Otis Ferguson: “You realize while wiping your eyes well into the second handkerchief that it is nothing so much as a hodgepodge of skylarking.” But as Siegel explains, when the bad jokes relentlessly pile on, they reduce “language to sounds, intellectual life to disorder, and emotional life to physical gestures.” In the wake of this nihilistic force, our only physical response can be laughter. The Marx Brothers’ humor therefore exists “on the threshold of first and last things—that is to say, philosophy.”

When Groucho first encounters Harpo in Duck Soup, he asks him who he is, and Harpo answers by rolling up his sleeve and revealing a tattooed image of his own face. This answer transforms Groucho’s social request for an introduction into a fundamental philosophical question: Can we ever pinpoint a person’s true identity? It also asks an even more fundamental question about representation in language: How can we point to something in the world with complete accuracy, without also being meaninglessly redundant? Harpo’s answer to “who are you?” is a visual-gag version of the Buddha’s infuriatingly honest answer to the same question. When asked who he was, he would say, gesturing to himself: I am thathagatha (the one who is like this).

When people talk about comedians as philosophers, they often mention George Carlin, Sam Kinison, or Louis C.K. These are comics whose jokes contain broader wisdom about human nature, society, language, and sometimes the humor of existence itself. These comedians are people with Something to Say. But Groucho doesn’t have anything to say. (And Harpo, for that matter, has literally nothing to say.) For Groucho it is the aggressive lack of agenda that makes him more than just a philosopher—that makes him a living philosophical force, a human argument against any attempt to make meaning of anything or stand for something. The refrain of his introductory song in Horse Feathers: “Whatever it is, I’m against it.” At the same time, standing for nothing also lets him stand for anything: “Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them ... well, I have others.”

If this essay feels more like a philosophical treatise than a book review, that’s because Siegel’s book reads more like a philosophical treatise than a biography. And yet Siegel somehow manages to make this treatise a true page-turner and a lot of fun. He applies his own philosophical acuity to the personal and socio-political aspects of Groucho’s life. He exposes the paradox behind Groucho’s misogyny, without excusing it—Siegel points out that there is a conscious impotence in Groucho’s repeated insults of women, on-screen and off: “He makes certain that it is an expression of male weakness, not male strength.” Siegel’s theory is that Groucho’s attitude toward women was a symptom of early 20th-century Jewish humor, and a result of being personally frustrated with a weak father who was prone to theatrical expressions of authority and bravado.

Siegel’s understanding of Groucho’s Jewishness is layered with useful complexity. (This book is part of Yale University Press’Jewish Lives series.) He provides a close reading of Groucho’s famous line: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as a member.” Groucho used this line in a telegram he sent to resign from an actual high-brow social club to which he felt superior. Siegel reads the line as equally self-annihilating and triumphant. So Groucho is an example of an early 20th-century Jew asserting dominance over American society by making his role as a permanent outsider part of mainstream American culture.

Siegel sees a philosophical paradox in every facet of Groucho’s life and art. Interestingly enough, the one issue on which the book is consistently ambivalent about is whether we can call the Marx Brothers “funny.” I don’t think this is so much a critical oversight on Siegel’s part as it is a testament to the Marx Brothers’ genius, as well as proof for Siegel’s argument that the Marx Brothers’ comedy destroys everything, including comedy. Siegel provides multiple arguments for how the Brothers are “something more or less than funny,” or “too nihilistic for laughter.” But at the same time he repeatedly refers to them as “funny,” too. There is a missing argumentative step that the book seems afraid to articulate, maybe because it’s self-contradictory: that this comedy, which goes too far past comedy into pure nihilism, still works as comedy, and that this in itself is funny.

When Groucho first encounters Harpo in Duck Soup, he asks him who he is, and Harpo answers by rolling up his sleeve and revealing a tattooed image of his own face. This answer transforms Groucho’s social request for an introduction into a fundamental philosophical question: Can we ever pinpoint a person’s true identity? It also asks an even more fundamental question about representation in language: How can we point to something in the world with complete accuracy, without also being meaninglessly redundant? Harpo’s answer to “who are you?” is a visual-gag version of the Buddha’s infuriatingly honest answer to the same question. When asked who he was, he would say, gesturing to himself: I am thathagatha (the one who is like this).

When people talk about comedians as philosophers, they often mention George Carlin, Sam Kinison, or Louis C.K. These are comics whose jokes contain broader wisdom about human nature, society, language, and sometimes the humor of existence itself. These comedians are people with Something to Say. But Groucho doesn’t have anything to say. (And Harpo, for that matter, has literally nothing to say.) For Groucho it is the aggressive lack of agenda that makes him more than just a philosopher—that makes him a living philosophical force, a human argument against any attempt to make meaning of anything or stand for something. The refrain of his introductory song in Horse Feathers: “Whatever it is, I’m against it.” At the same time, standing for nothing also lets him stand for anything: “Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them ... well, I have others.”

If this essay feels more like a philosophical treatise than a book review, that’s because Siegel’s book reads more like a philosophical treatise than a biography. And yet Siegel somehow manages to make this treatise a true page-turner and a lot of fun. He applies his own philosophical acuity to the personal and socio-political aspects of Groucho’s life. He exposes the paradox behind Groucho’s misogyny, without excusing it—Siegel points out that there is a conscious impotence in Groucho’s repeated insults of women, on-screen and off: “He makes certain that it is an expression of male weakness, not male strength.” Siegel’s theory is that Groucho’s attitude toward women was a symptom of early 20th-century Jewish humor, and a result of being personally frustrated with a weak father who was prone to theatrical expressions of authority and bravado.

Siegel’s understanding of Groucho’s Jewishness is layered with useful complexity. (This book is part of Yale University Press’Jewish Lives series.) He provides a close reading of Groucho’s famous line: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as a member.” Groucho used this line in a telegram he sent to resign from an actual high-brow social club to which he felt superior. Siegel reads the line as equally self-annihilating and triumphant. So Groucho is an example of an early 20th-century Jew asserting dominance over American society by making his role as a permanent outsider part of mainstream American culture.

Siegel sees a philosophical paradox in every facet of Groucho’s life and art. Interestingly enough, the one issue on which the book is consistently ambivalent about is whether we can call the Marx Brothers “funny.” I don’t think this is so much a critical oversight on Siegel’s part as it is a testament to the Marx Brothers’ genius, as well as proof for Siegel’s argument that the Marx Brothers’ comedy destroys everything, including comedy. Siegel provides multiple arguments for how the Brothers are “something more or less than funny,” or “too nihilistic for laughter.” But at the same time he repeatedly refers to them as “funny,” too. There is a missing argumentative step that the book seems afraid to articulate, maybe because it’s self-contradictory: that this comedy, which goes too far past comedy into pure nihilism, still works as comedy, and that this in itself is funny.

Because when the chips are down, the balloon goes up, and there is no hope the sun will ever shine again, you laugh. More...

Siegel offers extended analysis about how, in its essence, their work is not comedic. He quotes a bit of funny dialogue from A Night in Casablanca and then adds to the dialogue some lines from a real recorded domestic fight between Groucho and his wife, to demonstrate how easily the comedy can be transformed into drama—that it is not “essentially funny.” This misses a larger point that the Marx Brothers (and this book) seem to be making, which is that nothing is funny in essence, or not funny in essence, that comedy and drama aren’t opposed, that nothing has any essence at all. And that when we notice this, we laugh.

Siegel offers extended analysis about how, in its essence, their work is not comedic. He quotes a bit of funny dialogue from A Night in Casablanca and then adds to the dialogue some lines from a real recorded domestic fight between Groucho and his wife, to demonstrate how easily the comedy can be transformed into drama—that it is not “essentially funny.” This misses a larger point that the Marx Brothers (and this book) seem to be making, which is that nothing is funny in essence, or not funny in essence, that comedy and drama aren’t opposed, that nothing has any essence at all. And that when we notice this, we laugh.

January 23, 2016

Heard on All Things Considered

Marx was known for frequently taking aim at the rich and powerful in his comedies — but a new biography suggests a more sinister side to Julius "Groucho" Marx.

"The conventional image of Groucho was that he was on the side of the little guy, and he spoke defiantly and insolently to powerful people and wealthy people," Lee Siegel, the author of Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, tells NPR's Michel Martin. "But my feeling is that Groucho was out to deflate everybody — that he was a thoroughgoing misanthrope."

Siegel says his work aimed to get behind the comic's commonly accepted image — and find the man behind the icon.

"I wanted to get at the roots of his humor, and I wanted to get at what made him an icon," Siegel says. "You know, I just don't like the word 'icon,' because it dries up all the energies that made the icon in the first place."

This provocative biography argues that the man who is the ‘central intelligence’ of the Marx Brothers indulged in radical, nihilistic truth-telling that masked his insecurity. Seriously?

Karl Whitney

Wednesday 20 April 2016

In 1967 Groucho Marx made what now seems an unlikely appearance on conservative pundit William F Buckley’s TV show Firing Line. The show typically consisted of Buckley, a starchy, uncomfortable screen presence, who gave the impression of looking down his nose at the camera, politely putting what were often quite barbed questions to that week’s guest. Whatever Buckley’s politics, it was serious television, with a solemn atmosphere somewhere between a civics lesson and a Sunday mass. To add to the formality, the discussion was moderated by a chairman. The subject Buckley and Marx would discuss: “Is the world funny?”

The programme was an hour long, and began amiably, if stiffly, as Buckley introduced his guest. Then in his mid-70s, Groucho, whose casual attire of a blue jacket, polo neck and grey plaid trousers contrasted with Buckley’s businesslike suit and tie, was still recognisable from his heyday, when as a member of the Marx Brothers he had leered and delivered comic non sequiturs (“One morning I shot an elephant in my pyjamas. How he got in my pyjamas I don’t know”) over the course of vaudeville shows, Broadway productions and a run of classic, and some not so classic, comedy movies.

When he sat down to debate with Buckley, the greasepaint moustache and bushy eyebrows were long gone, but he was smoking his trademark cigar. He began to answer questions quite seriously, and it turned out that Groucho didn’t think the world was funny after all. Was he serious or funny? Where did the persona stop and the real Groucho begin? Lee Siegel wrestles with these questions in his provocative and perverse short critical biography of the man he calls the Marx Brothers’ “central intelligence”.

Siegel identifies a moment in the Buckley interview where Groucho goes on the attack by pointing out that the host blushes “like a young girl”. Groucho’s comedy, Siegel insists, is actually radical, nihilistic truth-telling that masks the great comedian’s insecurity; its origins lie in his childhood, with his domineering mother and weak father, and his thwarted intellectual ambitions. A quiet middle child born as Julius Marx to European Jewish emigrants, who lived on the upper east side of Manhattan, Groucho wanted to be a doctor, but instead had to leave school young to join his brothers in show business.

You might think that consistently arguing that the Marx Brothers aren’t funny is a difficult trick to pull off, and you’d be right, but it is central to Siegel’s theory that the Marxes were the same onscreen as they were off, that there was “a seamless continuity between their actual personas and their stage personas … fusing their entertainment selves with their real selves”. Instead of making riotous film comedies that seemed to fizz from the screen, they “dissolved the boundary between life and art, public and private”. It is difficult to decide whether his is a strongly held belief or a confrontational pose.

Putting aside the obvious differences between Groucho, Chico and Harpo in and out of character (Groucho’s moustache was fake; Chico, of course, wasn’t Italian; and Harpo could speak), there is considerable evidence that elements of the stage personae – Groucho’s stinginess, Chico’s gambling and womanising, and Harpo’s, well … harp playing – were the brother’s real-life attributes. After all, the stage names originated as nicknames reputedly given to them by the performer Art Fisher during a card game in 1915. The names stuck, onstage and off.

I have been a fan of the Marx Brothers since I was a child, in the early 1980s, when television stations used to fill blank spaces in the schedule with Duck Soup or Animal Crackers or A Night at the Opera, and I am as guilty of idealising their act as anyone. But even I can see the plausibility of Siegel’s version of Groucho as not a nice, avuncular figure but rather an asshole telling everyone what he really thinks of them. Where I would differ from Siegel would be in finding an asshole telling everyone what he really thinks of them funny, especially within the structure of a 1930s comedy movie.

As a child I loved the Marx Brothers’ wild energy, the way they bounced around the creaky confines of their films, intersecting awkwardly with banal, romantic subplots and subverting the musical numbers through bad dancing and off-key singing. There is no doubt that something about them had an effect on me that was more potent than the spell cast by Chaplin or, say, Abbott and Costello. Could that something have been the “shocking truthfulness” that Siegel identifies in their work?

Perhaps. But Siegel’s insistence on their unfunniness leads him into some fairly reductive and unconvincing analyses. In one memorable scene from Duck Soup, Harpo, playing a peanut vendor, teams up with Chico to infuriate a rival lemonade seller, driving him to the brink of madness. Siegel, rather unexpectedly, points out that the lemonade salesman “has done nothing wrong”, and claims that Duck Soup, supposedly an anti-fascist satire, is “actually a tour de force of undemocratic, even antidemocratic, sentiments”.

He compares their comedy unfavourably with the satire of Jonathan Swift, finding in their work no moral framework, “no stable point … from which the satire is made. Every position is invalidated, exposed to derision”. But surely such unstable, hedonistic and destructive derision is the fuel that drives their comedy? Morality seems irrelevant.

After the relative commercial failure of Duck Soup, which cut back on musical numbers and romantic subplot, the brothers moved from Paramount to MGM, where they made A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races – crowd-pleasing, well-made films that embedded the brothers in a social situation and prioritised the dreaded boy-girl storyline. One would think Siegel, who criticises Groucho’s general inability to appear “in a specific social context”, would be happy. But, no: “unfunny”.

Yet he is extremely sharp on why the Marxes were so successful as a comedy team: “at a time of rapid transition from vaudeville to silent film to talkies, [they] comprised an original synthesis of all three styles”. He is also good when addressing Groucho’s tetchiness about his origins, and his prickly relationship with high culture, especially the literary world (he conducted a passive-aggressive correspondence with TS Eliot).

There is a joke that dates back to the Marx Brothers’ Broadway play I’ll Say She Is!. Chico says: “The garbage man is here”, and Groucho replies: “Well, tell him we don’t want any.” Siegel writes that it’s “not funny”, but when, during his interview with Groucho, Buckley repeats the gag, the previously silent Firing Lineaudience laughs. Surely the joke is bombproof if even the staid Buckley can raise a chuckle with it? Groucho began the show by admitting that he is a “sad man”, but as the discussion progressed, he started to arch his back, wave the cigar, joke with the chairman and play to the audience. It is as if a switch has been flipped, and the old Groucho character has come to life again.

Perhaps the Groucho persona was just an act. In the late 1940s, as the Marx Brothers’ film career ground to a halt, Groucho began to host the quiz show You Bet Your Life, first on radio and then on TV. Siegel sees this as the point at which his personality and persona “merged comfortably, definitively, in full public view”. Yet when the producers of the show asked Groucho to wear the greasepaint and frock coat, he told them “the hell I will. That character’s dead. I’ll never go into that again.”

No comments:

Post a Comment