Saturday, 30 April 2016

Friday, 29 April 2016

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence - reviews

Groucho Marx’s Comedy Is Pure, Bleak Nihilism

So why does it make us laugh?

http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/books/2016/01/groucho_marx_the_comedy_of_existence_by_lee_siegel_reviewed.html

Groucho Marx Spared No One — And His Biographer Isn't Pulling Punches, Either

January 23, 2016

Heard on All Things Considered

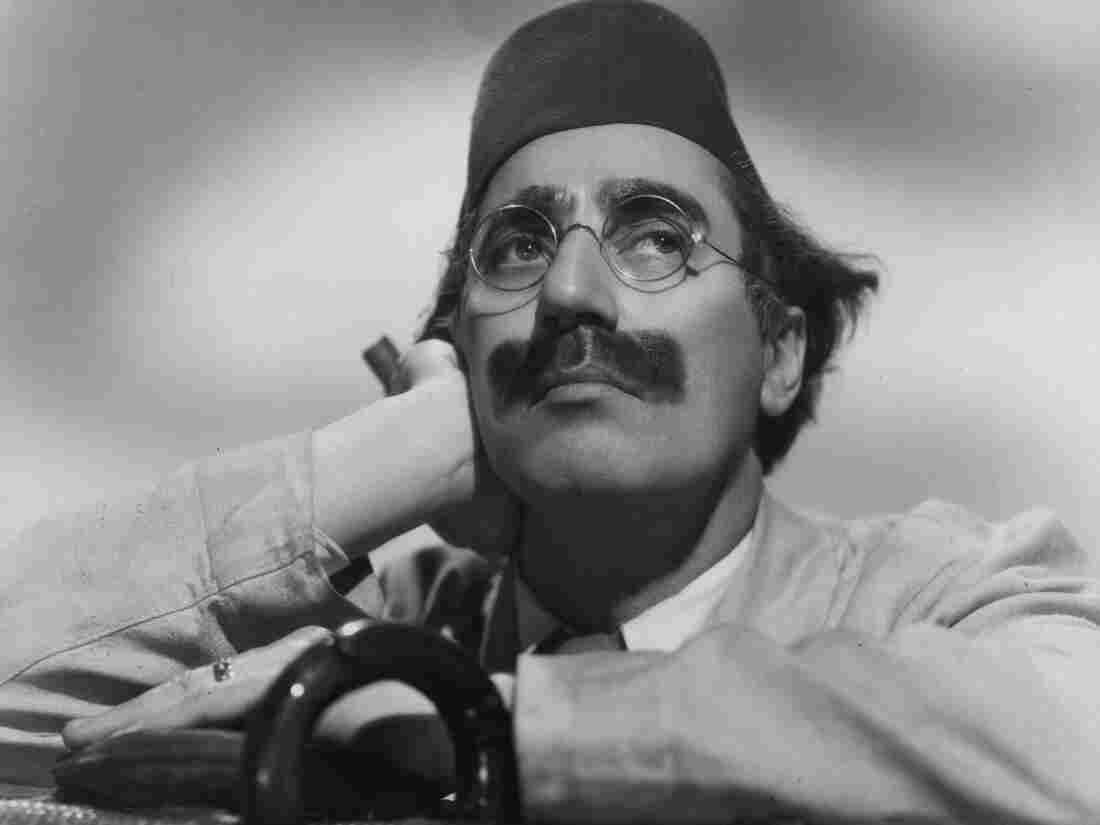

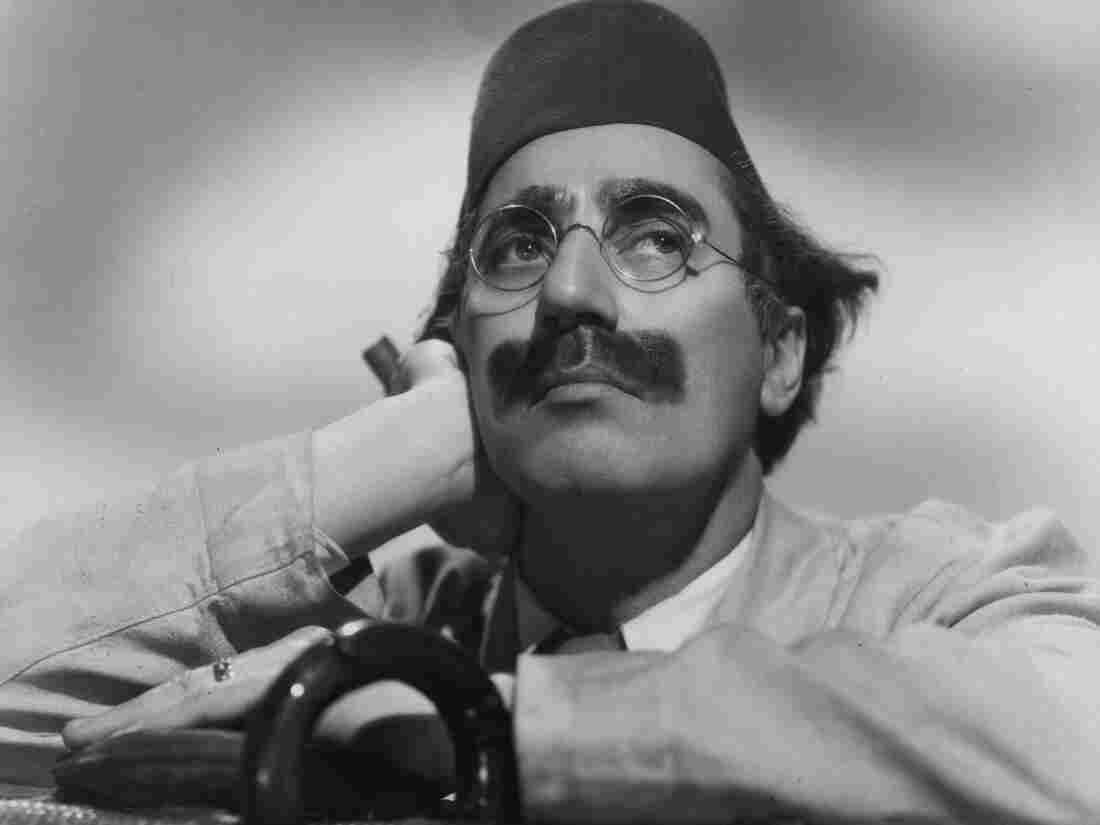

While not everyone has seen Groucho Marx's films, many people would still recognize the comedian. His bushy black eyebrows, thick mustache and ever-present cigar have long been iconic.

Marx was known for frequently taking aim at the rich and powerful in his comedies — but a new biography suggests a more sinister side to Julius "Groucho" Marx.

"The conventional image of Groucho was that he was on the side of the little guy, and he spoke defiantly and insolently to powerful people and wealthy people," Lee Siegel, the author of Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, tells NPR's Michel Martin. "But my feeling is that Groucho was out to deflate everybody — that he was a thoroughgoing misanthrope."

Siegel says his work aimed to get behind the comic's commonly accepted image — and find the man behind the icon.

"I wanted to get at the roots of his humor, and I wanted to get at what made him an icon," Siegel says. "You know, I just don't like the word 'icon,' because it dries up all the energies that made the icon in the first place."

http://www.npr.org/2016/01/23/464125023/the-comedy-of-existence-says-groucho-marx-went-after-everyone

Groucho Marx by Lee Siegel review – apparently, he wasn’t funny

This provocative biography argues that the man who is the ‘central intelligence’ of the Marx Brothers indulged in radical, nihilistic truth-telling that masked his insecurity. Seriously?

Karl Whitney

Wednesday 20 April 2016

In 1967 Groucho Marx made what now seems an unlikely appearance on conservative pundit William F Buckley’s TV show Firing Line. The show typically consisted of Buckley, a starchy, uncomfortable screen presence, who gave the impression of looking down his nose at the camera, politely putting what were often quite barbed questions to that week’s guest. Whatever Buckley’s politics, it was serious television, with a solemn atmosphere somewhere between a civics lesson and a Sunday mass. To add to the formality, the discussion was moderated by a chairman. The subject Buckley and Marx would discuss: “Is the world funny?”

The programme was an hour long, and began amiably, if stiffly, as Buckley introduced his guest. Then in his mid-70s, Groucho, whose casual attire of a blue jacket, polo neck and grey plaid trousers contrasted with Buckley’s businesslike suit and tie, was still recognisable from his heyday, when as a member of the Marx Brothers he had leered and delivered comic non sequiturs (“One morning I shot an elephant in my pyjamas. How he got in my pyjamas I don’t know”) over the course of vaudeville shows, Broadway productions and a run of classic, and some not so classic, comedy movies.

When he sat down to debate with Buckley, the greasepaint moustache and bushy eyebrows were long gone, but he was smoking his trademark cigar. He began to answer questions quite seriously, and it turned out that Groucho didn’t think the world was funny after all. Was he serious or funny? Where did the persona stop and the real Groucho begin? Lee Siegel wrestles with these questions in his provocative and perverse short critical biography of the man he calls the Marx Brothers’ “central intelligence”.

Siegel identifies a moment in the Buckley interview where Groucho goes on the attack by pointing out that the host blushes “like a young girl”. Groucho’s comedy, Siegel insists, is actually radical, nihilistic truth-telling that masks the great comedian’s insecurity; its origins lie in his childhood, with his domineering mother and weak father, and his thwarted intellectual ambitions. A quiet middle child born as Julius Marx to European Jewish emigrants, who lived on the upper east side of Manhattan, Groucho wanted to be a doctor, but instead had to leave school young to join his brothers in show business.

You might think that consistently arguing that the Marx Brothers aren’t funny is a difficult trick to pull off, and you’d be right, but it is central to Siegel’s theory that the Marxes were the same onscreen as they were off, that there was “a seamless continuity between their actual personas and their stage personas … fusing their entertainment selves with their real selves”. Instead of making riotous film comedies that seemed to fizz from the screen, they “dissolved the boundary between life and art, public and private”. It is difficult to decide whether his is a strongly held belief or a confrontational pose.

Putting aside the obvious differences between Groucho, Chico and Harpo in and out of character (Groucho’s moustache was fake; Chico, of course, wasn’t Italian; and Harpo could speak), there is considerable evidence that elements of the stage personae – Groucho’s stinginess, Chico’s gambling and womanising, and Harpo’s, well … harp playing – were the brother’s real-life attributes. After all, the stage names originated as nicknames reputedly given to them by the performer Art Fisher during a card game in 1915. The names stuck, onstage and off.

I have been a fan of the Marx Brothers since I was a child, in the early 1980s, when television stations used to fill blank spaces in the schedule with Duck Soup or Animal Crackers or A Night at the Opera, and I am as guilty of idealising their act as anyone. But even I can see the plausibility of Siegel’s version of Groucho as not a nice, avuncular figure but rather an asshole telling everyone what he really thinks of them. Where I would differ from Siegel would be in finding an asshole telling everyone what he really thinks of them funny, especially within the structure of a 1930s comedy movie.

As a child I loved the Marx Brothers’ wild energy, the way they bounced around the creaky confines of their films, intersecting awkwardly with banal, romantic subplots and subverting the musical numbers through bad dancing and off-key singing. There is no doubt that something about them had an effect on me that was more potent than the spell cast by Chaplin or, say, Abbott and Costello. Could that something have been the “shocking truthfulness” that Siegel identifies in their work?

Perhaps. But Siegel’s insistence on their unfunniness leads him into some fairly reductive and unconvincing analyses. In one memorable scene from Duck Soup, Harpo, playing a peanut vendor, teams up with Chico to infuriate a rival lemonade seller, driving him to the brink of madness. Siegel, rather unexpectedly, points out that the lemonade salesman “has done nothing wrong”, and claims that Duck Soup, supposedly an anti-fascist satire, is “actually a tour de force of undemocratic, even antidemocratic, sentiments”.

He compares their comedy unfavourably with the satire of Jonathan Swift, finding in their work no moral framework, “no stable point … from which the satire is made. Every position is invalidated, exposed to derision”. But surely such unstable, hedonistic and destructive derision is the fuel that drives their comedy? Morality seems irrelevant.

After the relative commercial failure of Duck Soup, which cut back on musical numbers and romantic subplot, the brothers moved from Paramount to MGM, where they made A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races – crowd-pleasing, well-made films that embedded the brothers in a social situation and prioritised the dreaded boy-girl storyline. One would think Siegel, who criticises Groucho’s general inability to appear “in a specific social context”, would be happy. But, no: “unfunny”.

Yet he is extremely sharp on why the Marxes were so successful as a comedy team: “at a time of rapid transition from vaudeville to silent film to talkies, [they] comprised an original synthesis of all three styles”. He is also good when addressing Groucho’s tetchiness about his origins, and his prickly relationship with high culture, especially the literary world (he conducted a passive-aggressive correspondence with TS Eliot).

There is a joke that dates back to the Marx Brothers’ Broadway play I’ll Say She Is!. Chico says: “The garbage man is here”, and Groucho replies: “Well, tell him we don’t want any.” Siegel writes that it’s “not funny”, but when, during his interview with Groucho, Buckley repeats the gag, the previously silent Firing Lineaudience laughs. Surely the joke is bombproof if even the staid Buckley can raise a chuckle with it? Groucho began the show by admitting that he is a “sad man”, but as the discussion progressed, he started to arch his back, wave the cigar, joke with the chairman and play to the audience. It is as if a switch has been flipped, and the old Groucho character has come to life again.

Perhaps the Groucho persona was just an act. In the late 1940s, as the Marx Brothers’ film career ground to a halt, Groucho began to host the quiz show You Bet Your Life, first on radio and then on TV. Siegel sees this as the point at which his personality and persona “merged comfortably, definitively, in full public view”. Yet when the producers of the show asked Groucho to wear the greasepaint and frock coat, he told them “the hell I will. That character’s dead. I’ll never go into that again.”

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/20/groucho-marx-the-comedy-of-existence-lee-siegel-review-biography

So why does it make us laugh?

Shon Arieh-Lerer

”If you are in a sexy mood the night you read [my autobiography], it may stimulate you beyond recognition and rekindle memories that you haven’t recalled in years.”

This sentence was written in a personal letter by Groucho Marx to his frenemy, T.S. Eliot. Groucho had dropped out of elementary school, and for the rest of his life strove to prove himself a man of letters, as well as to discredit men of letters. In both his private and public humor he relied heavily on words, yet had a knack for exposing all words as ultimately contentless. Hence his desire to have Eliot read his autobiography—thereby legitimizing it—as well as his need to deflate the great poet into an impotent man with a “sexy mood,” but no recent sexual activity.

This account of Groucho’s correspondence with Eliot is among a number of revealing scenes in Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, and as the book is a critical biography, all such scenes are in service of a literary and philosophical analysis. This is what explicitly distinguishes this book from previous Marx biographies: In Siegel’s hands, the details of Groucho’s life are less interesting than the broader literary argument that they illustrate, which Groucho would have found both deeply validating and kind of annoying. To any literarily or philosophically inclined Groucho fan, however, the book is a luminous delight.

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence is in itself a kind of funny title. Not only does it feature the scientifically funny hard-C sound, but it’s also deeply pretentious. And pretentiousness, being a form of ego-inflation, is among comedy’s most reliable targets. So it’s a self-defeating title: a reader who understands the comedy of existence would also make fun of the phrase “the comedy of existence.” Inspired paradox is at the heart of Siegel’s understanding of Groucho. He argues that the Marx Brothers’ comedy seeks to destroy everything, including the possibility of comedy itself. “Well, all the jokes can’t be good,” says Groucho in Animal Crackers. “You’ve got to expect that once in a while.”

”If you are in a sexy mood the night you read [my autobiography], it may stimulate you beyond recognition and rekindle memories that you haven’t recalled in years.”

This sentence was written in a personal letter by Groucho Marx to his frenemy, T.S. Eliot. Groucho had dropped out of elementary school, and for the rest of his life strove to prove himself a man of letters, as well as to discredit men of letters. In both his private and public humor he relied heavily on words, yet had a knack for exposing all words as ultimately contentless. Hence his desire to have Eliot read his autobiography—thereby legitimizing it—as well as his need to deflate the great poet into an impotent man with a “sexy mood,” but no recent sexual activity.

This account of Groucho’s correspondence with Eliot is among a number of revealing scenes in Lee Siegel’s Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, and as the book is a critical biography, all such scenes are in service of a literary and philosophical analysis. This is what explicitly distinguishes this book from previous Marx biographies: In Siegel’s hands, the details of Groucho’s life are less interesting than the broader literary argument that they illustrate, which Groucho would have found both deeply validating and kind of annoying. To any literarily or philosophically inclined Groucho fan, however, the book is a luminous delight.

Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence is in itself a kind of funny title. Not only does it feature the scientifically funny hard-C sound, but it’s also deeply pretentious. And pretentiousness, being a form of ego-inflation, is among comedy’s most reliable targets. So it’s a self-defeating title: a reader who understands the comedy of existence would also make fun of the phrase “the comedy of existence.” Inspired paradox is at the heart of Siegel’s understanding of Groucho. He argues that the Marx Brothers’ comedy seeks to destroy everything, including the possibility of comedy itself. “Well, all the jokes can’t be good,” says Groucho in Animal Crackers. “You’ve got to expect that once in a while.”

Siegel observes that the Brothers routinely let loose streams of cascading puns, malapropisms, word associations, and seemingly pointless slapstick that are perplexingly bad and often aggressively anti-comedic, but taken collectively become overwhelming, and thereby hilarious. In the words of the 1930s film critic Otis Ferguson: “You realize while wiping your eyes well into the second handkerchief that it is nothing so much as a hodgepodge of skylarking.” But as Siegel explains, when the bad jokes relentlessly pile on, they reduce “language to sounds, intellectual life to disorder, and emotional life to physical gestures.” In the wake of this nihilistic force, our only physical response can be laughter. The Marx Brothers’ humor therefore exists “on the threshold of first and last things—that is to say, philosophy.”

When Groucho first encounters Harpo in Duck Soup, he asks him who he is, and Harpo answers by rolling up his sleeve and revealing a tattooed image of his own face. This answer transforms Groucho’s social request for an introduction into a fundamental philosophical question: Can we ever pinpoint a person’s true identity? It also asks an even more fundamental question about representation in language: How can we point to something in the world with complete accuracy, without also being meaninglessly redundant? Harpo’s answer to “who are you?” is a visual-gag version of the Buddha’s infuriatingly honest answer to the same question. When asked who he was, he would say, gesturing to himself: I am thathagatha (the one who is like this).

When people talk about comedians as philosophers, they often mention George Carlin, Sam Kinison, or Louis C.K. These are comics whose jokes contain broader wisdom about human nature, society, language, and sometimes the humor of existence itself. These comedians are people with Something to Say. But Groucho doesn’t have anything to say. (And Harpo, for that matter, has literally nothing to say.) For Groucho it is the aggressive lack of agenda that makes him more than just a philosopher—that makes him a living philosophical force, a human argument against any attempt to make meaning of anything or stand for something. The refrain of his introductory song in Horse Feathers: “Whatever it is, I’m against it.” At the same time, standing for nothing also lets him stand for anything: “Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them ... well, I have others.”

If this essay feels more like a philosophical treatise than a book review, that’s because Siegel’s book reads more like a philosophical treatise than a biography. And yet Siegel somehow manages to make this treatise a true page-turner and a lot of fun. He applies his own philosophical acuity to the personal and socio-political aspects of Groucho’s life. He exposes the paradox behind Groucho’s misogyny, without excusing it—Siegel points out that there is a conscious impotence in Groucho’s repeated insults of women, on-screen and off: “He makes certain that it is an expression of male weakness, not male strength.” Siegel’s theory is that Groucho’s attitude toward women was a symptom of early 20th-century Jewish humor, and a result of being personally frustrated with a weak father who was prone to theatrical expressions of authority and bravado.

Siegel’s understanding of Groucho’s Jewishness is layered with useful complexity. (This book is part of Yale University Press’Jewish Lives series.) He provides a close reading of Groucho’s famous line: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as a member.” Groucho used this line in a telegram he sent to resign from an actual high-brow social club to which he felt superior. Siegel reads the line as equally self-annihilating and triumphant. So Groucho is an example of an early 20th-century Jew asserting dominance over American society by making his role as a permanent outsider part of mainstream American culture.

Siegel sees a philosophical paradox in every facet of Groucho’s life and art. Interestingly enough, the one issue on which the book is consistently ambivalent about is whether we can call the Marx Brothers “funny.” I don’t think this is so much a critical oversight on Siegel’s part as it is a testament to the Marx Brothers’ genius, as well as proof for Siegel’s argument that the Marx Brothers’ comedy destroys everything, including comedy. Siegel provides multiple arguments for how the Brothers are “something more or less than funny,” or “too nihilistic for laughter.” But at the same time he repeatedly refers to them as “funny,” too. There is a missing argumentative step that the book seems afraid to articulate, maybe because it’s self-contradictory: that this comedy, which goes too far past comedy into pure nihilism, still works as comedy, and that this in itself is funny.

When Groucho first encounters Harpo in Duck Soup, he asks him who he is, and Harpo answers by rolling up his sleeve and revealing a tattooed image of his own face. This answer transforms Groucho’s social request for an introduction into a fundamental philosophical question: Can we ever pinpoint a person’s true identity? It also asks an even more fundamental question about representation in language: How can we point to something in the world with complete accuracy, without also being meaninglessly redundant? Harpo’s answer to “who are you?” is a visual-gag version of the Buddha’s infuriatingly honest answer to the same question. When asked who he was, he would say, gesturing to himself: I am thathagatha (the one who is like this).

When people talk about comedians as philosophers, they often mention George Carlin, Sam Kinison, or Louis C.K. These are comics whose jokes contain broader wisdom about human nature, society, language, and sometimes the humor of existence itself. These comedians are people with Something to Say. But Groucho doesn’t have anything to say. (And Harpo, for that matter, has literally nothing to say.) For Groucho it is the aggressive lack of agenda that makes him more than just a philosopher—that makes him a living philosophical force, a human argument against any attempt to make meaning of anything or stand for something. The refrain of his introductory song in Horse Feathers: “Whatever it is, I’m against it.” At the same time, standing for nothing also lets him stand for anything: “Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them ... well, I have others.”

If this essay feels more like a philosophical treatise than a book review, that’s because Siegel’s book reads more like a philosophical treatise than a biography. And yet Siegel somehow manages to make this treatise a true page-turner and a lot of fun. He applies his own philosophical acuity to the personal and socio-political aspects of Groucho’s life. He exposes the paradox behind Groucho’s misogyny, without excusing it—Siegel points out that there is a conscious impotence in Groucho’s repeated insults of women, on-screen and off: “He makes certain that it is an expression of male weakness, not male strength.” Siegel’s theory is that Groucho’s attitude toward women was a symptom of early 20th-century Jewish humor, and a result of being personally frustrated with a weak father who was prone to theatrical expressions of authority and bravado.

Siegel’s understanding of Groucho’s Jewishness is layered with useful complexity. (This book is part of Yale University Press’Jewish Lives series.) He provides a close reading of Groucho’s famous line: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as a member.” Groucho used this line in a telegram he sent to resign from an actual high-brow social club to which he felt superior. Siegel reads the line as equally self-annihilating and triumphant. So Groucho is an example of an early 20th-century Jew asserting dominance over American society by making his role as a permanent outsider part of mainstream American culture.

Siegel sees a philosophical paradox in every facet of Groucho’s life and art. Interestingly enough, the one issue on which the book is consistently ambivalent about is whether we can call the Marx Brothers “funny.” I don’t think this is so much a critical oversight on Siegel’s part as it is a testament to the Marx Brothers’ genius, as well as proof for Siegel’s argument that the Marx Brothers’ comedy destroys everything, including comedy. Siegel provides multiple arguments for how the Brothers are “something more or less than funny,” or “too nihilistic for laughter.” But at the same time he repeatedly refers to them as “funny,” too. There is a missing argumentative step that the book seems afraid to articulate, maybe because it’s self-contradictory: that this comedy, which goes too far past comedy into pure nihilism, still works as comedy, and that this in itself is funny.

Because when the chips are down, the balloon goes up, and there is no hope the sun will ever shine again, you laugh. More...

Siegel offers extended analysis about how, in its essence, their work is not comedic. He quotes a bit of funny dialogue from A Night in Casablanca and then adds to the dialogue some lines from a real recorded domestic fight between Groucho and his wife, to demonstrate how easily the comedy can be transformed into drama—that it is not “essentially funny.” This misses a larger point that the Marx Brothers (and this book) seem to be making, which is that nothing is funny in essence, or not funny in essence, that comedy and drama aren’t opposed, that nothing has any essence at all. And that when we notice this, we laugh.

Siegel offers extended analysis about how, in its essence, their work is not comedic. He quotes a bit of funny dialogue from A Night in Casablanca and then adds to the dialogue some lines from a real recorded domestic fight between Groucho and his wife, to demonstrate how easily the comedy can be transformed into drama—that it is not “essentially funny.” This misses a larger point that the Marx Brothers (and this book) seem to be making, which is that nothing is funny in essence, or not funny in essence, that comedy and drama aren’t opposed, that nothing has any essence at all. And that when we notice this, we laugh.

January 23, 2016

Heard on All Things Considered

Marx was known for frequently taking aim at the rich and powerful in his comedies — but a new biography suggests a more sinister side to Julius "Groucho" Marx.

"The conventional image of Groucho was that he was on the side of the little guy, and he spoke defiantly and insolently to powerful people and wealthy people," Lee Siegel, the author of Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence, tells NPR's Michel Martin. "But my feeling is that Groucho was out to deflate everybody — that he was a thoroughgoing misanthrope."

Siegel says his work aimed to get behind the comic's commonly accepted image — and find the man behind the icon.

"I wanted to get at the roots of his humor, and I wanted to get at what made him an icon," Siegel says. "You know, I just don't like the word 'icon,' because it dries up all the energies that made the icon in the first place."

This provocative biography argues that the man who is the ‘central intelligence’ of the Marx Brothers indulged in radical, nihilistic truth-telling that masked his insecurity. Seriously?

Karl Whitney

Wednesday 20 April 2016

In 1967 Groucho Marx made what now seems an unlikely appearance on conservative pundit William F Buckley’s TV show Firing Line. The show typically consisted of Buckley, a starchy, uncomfortable screen presence, who gave the impression of looking down his nose at the camera, politely putting what were often quite barbed questions to that week’s guest. Whatever Buckley’s politics, it was serious television, with a solemn atmosphere somewhere between a civics lesson and a Sunday mass. To add to the formality, the discussion was moderated by a chairman. The subject Buckley and Marx would discuss: “Is the world funny?”

The programme was an hour long, and began amiably, if stiffly, as Buckley introduced his guest. Then in his mid-70s, Groucho, whose casual attire of a blue jacket, polo neck and grey plaid trousers contrasted with Buckley’s businesslike suit and tie, was still recognisable from his heyday, when as a member of the Marx Brothers he had leered and delivered comic non sequiturs (“One morning I shot an elephant in my pyjamas. How he got in my pyjamas I don’t know”) over the course of vaudeville shows, Broadway productions and a run of classic, and some not so classic, comedy movies.

When he sat down to debate with Buckley, the greasepaint moustache and bushy eyebrows were long gone, but he was smoking his trademark cigar. He began to answer questions quite seriously, and it turned out that Groucho didn’t think the world was funny after all. Was he serious or funny? Where did the persona stop and the real Groucho begin? Lee Siegel wrestles with these questions in his provocative and perverse short critical biography of the man he calls the Marx Brothers’ “central intelligence”.

Siegel identifies a moment in the Buckley interview where Groucho goes on the attack by pointing out that the host blushes “like a young girl”. Groucho’s comedy, Siegel insists, is actually radical, nihilistic truth-telling that masks the great comedian’s insecurity; its origins lie in his childhood, with his domineering mother and weak father, and his thwarted intellectual ambitions. A quiet middle child born as Julius Marx to European Jewish emigrants, who lived on the upper east side of Manhattan, Groucho wanted to be a doctor, but instead had to leave school young to join his brothers in show business.

You might think that consistently arguing that the Marx Brothers aren’t funny is a difficult trick to pull off, and you’d be right, but it is central to Siegel’s theory that the Marxes were the same onscreen as they were off, that there was “a seamless continuity between their actual personas and their stage personas … fusing their entertainment selves with their real selves”. Instead of making riotous film comedies that seemed to fizz from the screen, they “dissolved the boundary between life and art, public and private”. It is difficult to decide whether his is a strongly held belief or a confrontational pose.

Putting aside the obvious differences between Groucho, Chico and Harpo in and out of character (Groucho’s moustache was fake; Chico, of course, wasn’t Italian; and Harpo could speak), there is considerable evidence that elements of the stage personae – Groucho’s stinginess, Chico’s gambling and womanising, and Harpo’s, well … harp playing – were the brother’s real-life attributes. After all, the stage names originated as nicknames reputedly given to them by the performer Art Fisher during a card game in 1915. The names stuck, onstage and off.

I have been a fan of the Marx Brothers since I was a child, in the early 1980s, when television stations used to fill blank spaces in the schedule with Duck Soup or Animal Crackers or A Night at the Opera, and I am as guilty of idealising their act as anyone. But even I can see the plausibility of Siegel’s version of Groucho as not a nice, avuncular figure but rather an asshole telling everyone what he really thinks of them. Where I would differ from Siegel would be in finding an asshole telling everyone what he really thinks of them funny, especially within the structure of a 1930s comedy movie.

As a child I loved the Marx Brothers’ wild energy, the way they bounced around the creaky confines of their films, intersecting awkwardly with banal, romantic subplots and subverting the musical numbers through bad dancing and off-key singing. There is no doubt that something about them had an effect on me that was more potent than the spell cast by Chaplin or, say, Abbott and Costello. Could that something have been the “shocking truthfulness” that Siegel identifies in their work?

Perhaps. But Siegel’s insistence on their unfunniness leads him into some fairly reductive and unconvincing analyses. In one memorable scene from Duck Soup, Harpo, playing a peanut vendor, teams up with Chico to infuriate a rival lemonade seller, driving him to the brink of madness. Siegel, rather unexpectedly, points out that the lemonade salesman “has done nothing wrong”, and claims that Duck Soup, supposedly an anti-fascist satire, is “actually a tour de force of undemocratic, even antidemocratic, sentiments”.

He compares their comedy unfavourably with the satire of Jonathan Swift, finding in their work no moral framework, “no stable point … from which the satire is made. Every position is invalidated, exposed to derision”. But surely such unstable, hedonistic and destructive derision is the fuel that drives their comedy? Morality seems irrelevant.

After the relative commercial failure of Duck Soup, which cut back on musical numbers and romantic subplot, the brothers moved from Paramount to MGM, where they made A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races – crowd-pleasing, well-made films that embedded the brothers in a social situation and prioritised the dreaded boy-girl storyline. One would think Siegel, who criticises Groucho’s general inability to appear “in a specific social context”, would be happy. But, no: “unfunny”.

Yet he is extremely sharp on why the Marxes were so successful as a comedy team: “at a time of rapid transition from vaudeville to silent film to talkies, [they] comprised an original synthesis of all three styles”. He is also good when addressing Groucho’s tetchiness about his origins, and his prickly relationship with high culture, especially the literary world (he conducted a passive-aggressive correspondence with TS Eliot).

There is a joke that dates back to the Marx Brothers’ Broadway play I’ll Say She Is!. Chico says: “The garbage man is here”, and Groucho replies: “Well, tell him we don’t want any.” Siegel writes that it’s “not funny”, but when, during his interview with Groucho, Buckley repeats the gag, the previously silent Firing Lineaudience laughs. Surely the joke is bombproof if even the staid Buckley can raise a chuckle with it? Groucho began the show by admitting that he is a “sad man”, but as the discussion progressed, he started to arch his back, wave the cigar, joke with the chairman and play to the audience. It is as if a switch has been flipped, and the old Groucho character has come to life again.

Perhaps the Groucho persona was just an act. In the late 1940s, as the Marx Brothers’ film career ground to a halt, Groucho began to host the quiz show You Bet Your Life, first on radio and then on TV. Siegel sees this as the point at which his personality and persona “merged comfortably, definitively, in full public view”. Yet when the producers of the show asked Groucho to wear the greasepaint and frock coat, he told them “the hell I will. That character’s dead. I’ll never go into that again.”

Thursday, 28 April 2016

Last night's set lists

At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

Autumn Leaves

Need Your Love So Bad

The Way You Look Tonight

Da Elderly: -

My Friend The Sun

Into The Light

Baby What You Want Me To Do

The Elderly Brothers: -

All I Have To Do Is Dream

Let It Be Me

Things We Said Today

Baby It's You

Bring It On Home To Me

Bird Dog

You Got It

Given the cold weather and intermittent hail/rain, the meagre turnout wasn't such a surprise. Nonetheless a few hardy punters and stalwarts of the open mic night braved the elements. Not unexpectedly there were a couple of tributes to Prince - Purple Rain and Little Red Corvette. Yours truely debuted a Family song from 1972 and brought back, after a long absence, a favourite Jimmy Reed song from 1959.

Ron Elderly: -

Autumn Leaves

Need Your Love So Bad

The Way You Look Tonight

Da Elderly: -

My Friend The Sun

Into The Light

Baby What You Want Me To Do

The Elderly Brothers: -

All I Have To Do Is Dream

Let It Be Me

Things We Said Today

Baby It's You

Bring It On Home To Me

Bird Dog

You Got It

Given the cold weather and intermittent hail/rain, the meagre turnout wasn't such a surprise. Nonetheless a few hardy punters and stalwarts of the open mic night braved the elements. Not unexpectedly there were a couple of tributes to Prince - Purple Rain and Little Red Corvette. Yours truely debuted a Family song from 1972 and brought back, after a long absence, a favourite Jimmy Reed song from 1959.

Wednesday, 27 April 2016

Bill Evans: Some Other Time review

RESONANCE • 1968/2016

Some Other Time is a newly unearthed Bill Evans studio album, initially recorded in 1968 in Germany but not released until this month. It still sounds fresh and alive almost 50 years later.

Mark Richardson

Executive Editor

23 April 2016

Casual jazz fans know Bill Evans through his association with Miles Davis. Kind of Blue, the one jazz album you own if you only own one, features Evans on piano on four of the five tracks, and his brief liner notes sketch out the group's approach to improvisation in poetic and accessible terms. When you learn a bit more about Kind of Blue, you learn that Davis actually envisioned the record with Evans in mind. And though for years Davis was listed as the album's sole composer, Evans wrote "Blue in Green" (he eventually received credit.)

Another Kind of Blue piece, "Flamenco Sketches," was partly based on Evans' arrangement of "Some Other Time," the Leonard Bernstein standard. (Evans had earlier used the slow opening vamp as a building block to his breathtaking solo piano composition "Peace Piece"). So though he may not be an especially famous jazz musician, Bill Evans played an integral role in shaping the most famous jazz recording of all time, and the arc of his discography is a rewarding one for those branching off from classic Miles. "Some Other Time" continued to be a touchstone piece for Evans for the rest of his life, appearing regularly on his albums (notably on his duet record with Tony Bennett). And now it's become the title track to a newly unearthed studio album, one recorded in 1968 in Germany but not released until this month.

Jazz in general overflows with archival material. It's a live medium, and recordings of shows have been common since the early part of the last century. Studio LPs could typically be cut in a couple of days, which generally meant a wealth of unused songs and outtakes. But it's somewhat rare to have a true unreleased album—a collection of songs recorded together at a session with the thought of a specific release that never saw the light of day.

Some Other Time: The Lost Session From the Black Forest is one of these. It was recorded when Evans was on tour in Europe with a trio that included Eddie Gomez on bass and, on drums, a young Jack DeJohnette, who would go on to much greater fame with Miles Davis, Keith Jarrett, and as a leader himself. It was cut between stops on a European tour by German producer Joachim-Ernst Berendt, with the idea that the rights and a release plan would be figured out later. This particular group had only been documented on record just once, onAt the Montreux Jazz Festival, recorded five days prior to this date. So the existence of an unheard studio album by the trio is a significant addition to the Evans story.

23 April 2016

Casual jazz fans know Bill Evans through his association with Miles Davis. Kind of Blue, the one jazz album you own if you only own one, features Evans on piano on four of the five tracks, and his brief liner notes sketch out the group's approach to improvisation in poetic and accessible terms. When you learn a bit more about Kind of Blue, you learn that Davis actually envisioned the record with Evans in mind. And though for years Davis was listed as the album's sole composer, Evans wrote "Blue in Green" (he eventually received credit.)

Another Kind of Blue piece, "Flamenco Sketches," was partly based on Evans' arrangement of "Some Other Time," the Leonard Bernstein standard. (Evans had earlier used the slow opening vamp as a building block to his breathtaking solo piano composition "Peace Piece"). So though he may not be an especially famous jazz musician, Bill Evans played an integral role in shaping the most famous jazz recording of all time, and the arc of his discography is a rewarding one for those branching off from classic Miles. "Some Other Time" continued to be a touchstone piece for Evans for the rest of his life, appearing regularly on his albums (notably on his duet record with Tony Bennett). And now it's become the title track to a newly unearthed studio album, one recorded in 1968 in Germany but not released until this month.

Jazz in general overflows with archival material. It's a live medium, and recordings of shows have been common since the early part of the last century. Studio LPs could typically be cut in a couple of days, which generally meant a wealth of unused songs and outtakes. But it's somewhat rare to have a true unreleased album—a collection of songs recorded together at a session with the thought of a specific release that never saw the light of day.

Some Other Time: The Lost Session From the Black Forest is one of these. It was recorded when Evans was on tour in Europe with a trio that included Eddie Gomez on bass and, on drums, a young Jack DeJohnette, who would go on to much greater fame with Miles Davis, Keith Jarrett, and as a leader himself. It was cut between stops on a European tour by German producer Joachim-Ernst Berendt, with the idea that the rights and a release plan would be figured out later. This particular group had only been documented on record just once, onAt the Montreux Jazz Festival, recorded five days prior to this date. So the existence of an unheard studio album by the trio is a significant addition to the Evans story.

The piano/bass/drums trio setting is where Evans did his most important and lasting work. He thrived on both the limitations and the possibilities of the set-up, and returned to it constantly over the course of his quarter-century recording career. He generally favored truly collaborative improvising in the setup; the bassist in his trio was expected to contribute melodically and harmonically, in addition to rhythmically, and he could often be heard soloing alongside the pianist. Eddie Gomez, heard on this album, was a steady partner of Evans' for a decade, and the level of empathy between the two players is something to behold. On "What Kind of Fool Am I?," Gomez's dancing lines darts between Evans' bass notes, almost serving as a third hand on the piano. On the immortal title track, Gomez seems like half a conversation, accenting and commenting on Evans' melodic flourishes. For his part, DeJohnette offers tasteful and low-key accompaniment, heavy on the brushwork and soft textures on cymbals—he was more of a role-player at this point in his career. But the three together feel like a true unit.

The tracklist on Some Other Time is heavy on standards, with a few Evans original sprinkled in. To love the American songbook is to be in love with harmony, and Evans never stopped discovering new possibilities in old and frequently played songs. He had a way of phrasing chord progressions for maximum impact, and he used space as virtually another instrument. Evans recorded "My Funny Valentine" many times in a number of different arrangements, often uptempo, but here he drags it out into an achingly poignant ballad that picks up speed as it goes. In his autobiography, Miles Davis famously described Evans' tone as sounding like "like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall," and the tumble of notes on the faster sections of "My Funny Valentine" evince that crystalline loveliness. In addition to the material planned for the original LP, there's a second LP of outtakes and alternate versions that feels very much on par with the first disc.

Evans' art has endured in part because he has a brilliant combination of formal sophistication and accessibility; critics and his fellow musicians heard the genius in his approach to chords, his lightness of touch, and his open-eared support of others in his band, while listeners could put on his records and simply bask in their beauty, how Evans' continual foregrounding of emotion made the sad songs extra wrenching and the happy ones extra buoyant. He was sometimes criticized for an approach that could sound like "cocktail piano," meaning that it wasn't terribly heavy on dynamics and tended to be lower key and generally pretty, but this turned out to be another strength. If you wanted jazz in the background while engaging in another activity, Evans was your man, and if you wanted to listen closely and hear a standard like "Some Other Time" pushed to the limits of expression by his ear for space, he was there for that too.

Evans was one of those jazz artists who changed relatively little over the course of their career. His style developed and his sound had subtle shifts in emphasis over time, but his general approach to music was remarkably consistent, and he remained apart from most of the fashionable trends that wound through the jazz of his era. His first studio date as a leader, in 1956, was just a year after Charlie Parker's death, with bebop very much still au courant; his last, in 1979, the year before his death, was the year Chuck Mangione was nominated for a Grammy for the discofied light jazz funk of "Feels So Good." In both of those years, Evans recorded small-group acoustic jazz albums featuring his standard trio, playing a mix of standards and a few originals. About midway between those two bookends came this set, recorded in a small studio in Germany and left on the shelf, and it still sounds fresh and alive almost 50 years later.

Tuesday, 26 April 2016

Monday, 25 April 2016

Billy Paul RIP

Billy Paul obituary

American singer who scored a massive hit with the soul classic Me and Mrs Jones

Dave Laing

Monday 25 April 2016

Me and Mrs Jones, which tells the tale of a man’s infatuation with his married lover, was one of the classic soul songs of the 1970s. It was performed with jazzy cool by Billy Paul, who has died of pancreatic cancer aged 81. A key figure in the success of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff’s “Philly sound”, in his best performances Paul combined jazz technique with rhythm and blues fervour.

He was born Paul Williams in North Philadelphia. His was a musical family – and he studied his mother’s collection of jazz records by such singers as Nat King Cole and Billie Holiday. Paul made his first radio broadcast at the age of 11, before studying at the West Philadelphia Music school and the Granoff School of Music. At 16 he appeared at Club Harlem in Philadelphia on the same bill as the saxophonist Charlie Parker. Paul recalled that: “Bird told me if I kept struggling I’d go a long way; and I’ve never forgotten his words.”

He was soon playing at venues outside Pennsylvania – and in 1951, at the Apollo theatre in Harlem, New York, his manager persuaded him to create a stage name to avoid confusion with the saxophonist Paul Williams. In 1957 his career was interrupted by military service. Paul was posted to Germany, where his unit included both Elvis Presley and Gary Crosby, son of Bing. According to Paul, Elvis was not interested in playing music during his military service, but Paul and Crosby formed a jazz band which toured throughout Germany.

Returning to his civilian life, Paul resumed his career as a jazz singer, until in 1967, Gamble and Huff signed him to a recording deal. The first album, Feelin’ Good at the Cadillac Club (1968), was a recreation of Paul’s club act, but its successor, Ebony Woman (1970), added a more contemporary soul element. It sold enough copies to become a Top 20 hit on the soul charts.

In 1970, Gamble and Huff started their Philadelphia International label with backing from CBS Records. Following the Motown model, they set up their own studios, Sigma Sound, with its own group of session musicians. Paul became one of the label’s stalwarts, alongside Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, the O’Jays and Archie Bell.

Paul released the album Going East in 1971, before Me and Mrs Jones and its accompanying album, 360 Degrees of Billy Paul, made the commercial breakthrough the following year. A British reviewer attributed the song’s success to its “slyly insinuating mixture of iced vocal and emotive story line”.

The single sold over 2m copies in the US alone and became an international hit, reaching No 12 in Britain early in 1973. That year, Paul toured Europe with the O’Jays and the Intruders, recording a live album at the London show. Me and Mrs Jones went on to win the Grammy award for best male rhythm and blues vocal performance, despite strong competition from Ray Charles and Curtis Mayfield.

American singer who scored a massive hit with the soul classic Me and Mrs Jones

Dave Laing

Monday 25 April 2016

Me and Mrs Jones, which tells the tale of a man’s infatuation with his married lover, was one of the classic soul songs of the 1970s. It was performed with jazzy cool by Billy Paul, who has died of pancreatic cancer aged 81. A key figure in the success of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff’s “Philly sound”, in his best performances Paul combined jazz technique with rhythm and blues fervour.

He was born Paul Williams in North Philadelphia. His was a musical family – and he studied his mother’s collection of jazz records by such singers as Nat King Cole and Billie Holiday. Paul made his first radio broadcast at the age of 11, before studying at the West Philadelphia Music school and the Granoff School of Music. At 16 he appeared at Club Harlem in Philadelphia on the same bill as the saxophonist Charlie Parker. Paul recalled that: “Bird told me if I kept struggling I’d go a long way; and I’ve never forgotten his words.”

He was soon playing at venues outside Pennsylvania – and in 1951, at the Apollo theatre in Harlem, New York, his manager persuaded him to create a stage name to avoid confusion with the saxophonist Paul Williams. In 1957 his career was interrupted by military service. Paul was posted to Germany, where his unit included both Elvis Presley and Gary Crosby, son of Bing. According to Paul, Elvis was not interested in playing music during his military service, but Paul and Crosby formed a jazz band which toured throughout Germany.

Returning to his civilian life, Paul resumed his career as a jazz singer, until in 1967, Gamble and Huff signed him to a recording deal. The first album, Feelin’ Good at the Cadillac Club (1968), was a recreation of Paul’s club act, but its successor, Ebony Woman (1970), added a more contemporary soul element. It sold enough copies to become a Top 20 hit on the soul charts.

In 1970, Gamble and Huff started their Philadelphia International label with backing from CBS Records. Following the Motown model, they set up their own studios, Sigma Sound, with its own group of session musicians. Paul became one of the label’s stalwarts, alongside Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, the O’Jays and Archie Bell.

Paul released the album Going East in 1971, before Me and Mrs Jones and its accompanying album, 360 Degrees of Billy Paul, made the commercial breakthrough the following year. A British reviewer attributed the song’s success to its “slyly insinuating mixture of iced vocal and emotive story line”.

The single sold over 2m copies in the US alone and became an international hit, reaching No 12 in Britain early in 1973. That year, Paul toured Europe with the O’Jays and the Intruders, recording a live album at the London show. Me and Mrs Jones went on to win the Grammy award for best male rhythm and blues vocal performance, despite strong competition from Ray Charles and Curtis Mayfield.

The follow-up to Me and Mrs Jones was Am I Black Enough for You?, a controversial paean to black power which alienated many radio station managers and much of the white audience that had bought its predecessor. Paul’s only subsequent mainstream pop hit was to be Thanks for Saving My Life in 1974.*

His recordings nevertheless remained popular with black audiences, despite further controversy over the title of a 1976 single Let’s Make a Baby. Although the lyrics also had a strong black pride element in their reference to raising a child to “walk around with his head held tall”, the song’s sexual content led some moral leaders, including the Rev Jesse Jackson, to urge broadcasters to ban the disc.

Paul continued to record for Gamble and Huff’s company until 1980. A highlight of his later albums was a version of Paul McCartney’s song Let ’Em In, to whose lyrics Billy Paul added references to heroes of the civil rights struggle, including Malcolm X and Medgar Evers. Two decades later, Paul sued Philadelphia International for underpayment of royalties for Me and Mrs Jones and was awarded $500,000 by the jury.

In later years, he continued to appear at clubs and jazz festivals in the US and abroad. A biographical film, Am I Black Enough for You?, directed by Göran Hugo Olsson, was released in 2009.

After a brief period in hospital, Paul died at his home in Blackwood, New Jersey. He is survived by his wife, Blanche, who managed his career for many years.

• Billy Paul (Paul Williams) singer, born 1 December 1934; died 24 April 2016

* Although, in the UK, Let 'Em In got to No. 26 in 1977.

Wenger Out!

I say this, of course, with tongue firmly planted in cheek. Oh, the luxury of finishing in the top four almost every year and getting onto Europe. Oh, to have had a manager of his worth and intelligence over the last few years instead of Gullit, Pardew, Souness, Allardyce, Kinnear and Carver (Carver?!). Then again, oh, to have an owner who had some pride in his club and knew what he was doing...

Meanwhile, in the real world, we plunge inexorably down to the Championship.

Sunday, 24 April 2016

Dave and Phil Alvin with The Guilty Ones - review

Dave Alvin and Phil Alvin with the Guilty Ones, Manchester, Ruby Lounge, 18-04-16

By Little Bill Broonzy

When Dave and Phil Alvin took to the stage in Manchester’s Ruby Lounge on Monday night it was the latest chapter in one of the more heart-warming stories in rock’n’roll.

Known primarily as the co-founders of legendary roots rock band the Blasters, the brothers, tired of feuding, had long ago gone their separate ways. Dave, the Fender strutting songwriter in the band had grown weary of providing words for his big brother and lead vocalist Phil, so in 1986 he quit the Blasters.

Subsequently Dave went on to produce a string of critically acclaimed solo albums, with his band the Guilty Men, with most of the material being self penned. He won a Grammy in 2000 for his album of traditional material, “Public Domain”.

Phil meanwhile, returned to academia as a professor of mathematics at California State University, touring with the Blasters during semester breaks, playing to ever smaller audiences in bars around the USA. And thus the greatest voice in modern blues music faded into the background.

And so it may have remained had it not been for a health scare in July 2012, when Phil, touring in Spain with the Blasters was hospitalised with complications of MRSA. Whilst in a Spanish hospital he flat lined and was pronounced dead before being resuscitated by a young Spanish doctor.

This prompted a gradual reconciliation. In 2014 the brothers recorded their first studio album in 30 years. “Common Ground” a collection of Big Bill Broonzy covers was nominated for a Grammy in 2015. The Alvins toured the world with Dave’s latest band the Guilty Ones. Nobody got killed, and they decided to do it again.

Last year, they followed this up with the suitably titled “Lost Time”, another collection of traditional blues songs, ranging from the 30’s to the 50’s. This gig in Manchester was part of the UK tour to promote the album.

The venue was ideal; a grimy, dimly lit blues club with maybe 100 people in attendance. The band was supremely tight. Two lead guitarists, Dave and the exceptional Chris Miller taking it in turns to run searing solos; Brad Fordham keeping it tight on bass and the amazing Lisa Pankratz on drums.

But the star of the show is Big Phil. The whole set is geared around showcasing his gigantic singing voice, a musical instrument in itself. Dave restricts himself to a handful of vocals, all the time introducing songs with stories about his big brother, whilst Phil powers his way through a set comprising of blues standards, old Blasters songs and a couple of Dave’s more recent numbers.

The band played a straight two hour set which left the audience screaming for more. Highlights included the Blasters classics “American Music” and “Marie Marie”, plus blues standards like “Truckin Little Woman” and “World’s in a Bad Condition”. The Islington gig, which your reviewer was also lucky enough to attend, included an astonishing version of the James Brown classic “Please Please Please”, in which Phil Alvin brought the house down.

Throughout it all, the brothers displayed an easy going spirit of kinship and harmony which belied their turbulent past. Heart-warming, really. “Lost Time” indeed

By Little Bill Broonzy

When Dave and Phil Alvin took to the stage in Manchester’s Ruby Lounge on Monday night it was the latest chapter in one of the more heart-warming stories in rock’n’roll.

Known primarily as the co-founders of legendary roots rock band the Blasters, the brothers, tired of feuding, had long ago gone their separate ways. Dave, the Fender strutting songwriter in the band had grown weary of providing words for his big brother and lead vocalist Phil, so in 1986 he quit the Blasters.

Subsequently Dave went on to produce a string of critically acclaimed solo albums, with his band the Guilty Men, with most of the material being self penned. He won a Grammy in 2000 for his album of traditional material, “Public Domain”.

Phil meanwhile, returned to academia as a professor of mathematics at California State University, touring with the Blasters during semester breaks, playing to ever smaller audiences in bars around the USA. And thus the greatest voice in modern blues music faded into the background.

And so it may have remained had it not been for a health scare in July 2012, when Phil, touring in Spain with the Blasters was hospitalised with complications of MRSA. Whilst in a Spanish hospital he flat lined and was pronounced dead before being resuscitated by a young Spanish doctor.

This prompted a gradual reconciliation. In 2014 the brothers recorded their first studio album in 30 years. “Common Ground” a collection of Big Bill Broonzy covers was nominated for a Grammy in 2015. The Alvins toured the world with Dave’s latest band the Guilty Ones. Nobody got killed, and they decided to do it again.

Last year, they followed this up with the suitably titled “Lost Time”, another collection of traditional blues songs, ranging from the 30’s to the 50’s. This gig in Manchester was part of the UK tour to promote the album.

The venue was ideal; a grimy, dimly lit blues club with maybe 100 people in attendance. The band was supremely tight. Two lead guitarists, Dave and the exceptional Chris Miller taking it in turns to run searing solos; Brad Fordham keeping it tight on bass and the amazing Lisa Pankratz on drums.

But the star of the show is Big Phil. The whole set is geared around showcasing his gigantic singing voice, a musical instrument in itself. Dave restricts himself to a handful of vocals, all the time introducing songs with stories about his big brother, whilst Phil powers his way through a set comprising of blues standards, old Blasters songs and a couple of Dave’s more recent numbers.

The band played a straight two hour set which left the audience screaming for more. Highlights included the Blasters classics “American Music” and “Marie Marie”, plus blues standards like “Truckin Little Woman” and “World’s in a Bad Condition”. The Islington gig, which your reviewer was also lucky enough to attend, included an astonishing version of the James Brown classic “Please Please Please”, in which Phil Alvin brought the house down.

Throughout it all, the brothers displayed an easy going spirit of kinship and harmony which belied their turbulent past. Heart-warming, really. “Lost Time” indeed

Saturday, 23 April 2016

Friday, 22 April 2016

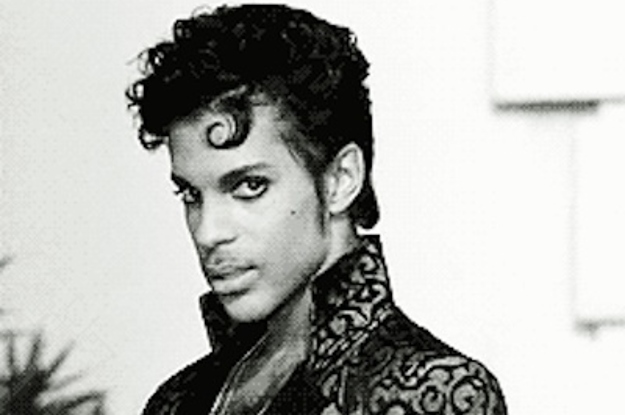

Prince RIP

Purple Rain singer whose sprawling career spanned decades and genres dies at his Paisley Park recording studio in his home state of Minnesota

Ed Pilkington, Harriet Gibsone and Amanda Holpuch

Thursday 21 April 2016

The unique and endlessly creative artist Prince has died at his Paisley Park home, outside Minneapolis, aged 57, leaving behind him a gaping hole in musical genres as diverse as R&B, rock, funk and pop.

The death was announced by his publicist Yvette Noel-Schure after police had been called to the premises which double as his music studio in the Minnesota city. No details were immediately given for the cause of death, though last week he was rushed to hospital apparently recovering from a bout of flu that had forced his private jet to make an emergency landing in Illinois.

The sudden death of the diminutive man who became such a towering musical figure, selling more than 100m records in a career of virtually unparalleled richness and unpredictability, prompted an emotional response across the music world. Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman, former members of Prince’s band the Revolution, said they were “completely shocked and devastated by the sudden loss of our brother, artist and friend, Prince”.

On Twitter, fellow musicians and celebrities vented barely contained grief. Boy George called Thursday “the worst day ever”; Katy Perry said: “And just like that … the world lost a lot of magic.” The Minneapolis-St Paul radio station 89.3, The Current, played his music on a permanent loop.

Barack Obama, who was flying from Saudi Arabia to London on Air Force One when the news broke, said he was mourning along with millions of fans. “Few artists have influenced the sound and trajectory of popular music more distinctly, or touched quite so many people with their talent. As one of the most gifted and prolific musicians of our time, Prince did it all.”

A statement from Carver County sheriff’s office said that when officers arrived at Paisley Park studios in Chanhassen they found Prince unresponsive in an elevator. “First responders attempted to provide lifesaving CPR, but were unable to revive the victim.”

He was pronounced dead at 10.07am. Police say they are continuing to investigate the circumstances of his death.

One thing was certain: Prince lived life to the fullest right up to his early demise. If anything, the workaholic who regularly slept three hours a night and would play impromptu concerts until dawn was accelerating the pace of his hectic schedule when he died.

He cut four albums in his last 18 months, and had let it be known he was writing a memoir that would be released next year. Hours after he was released from hospital, he announced on Saturday that he was going to throw a dance party at his music complex which he dubbed “Paisley Park After Dark”. He said tickets would cost just $10, and said of his recent tussle with flu: “Wait a few days before you waste any prayers.”

Standing just 5ft2in tall, Prince truly had an outsized influence on the world. Born in his beloved Minneapolis on 7 June 1958, his sprawling musical tastes, androgynous style, genre-bending imagination, sexual outrageousness and flirtation with religion left fans forever guessing about where he would go next.

His wry, almost satirical relationship with fame, combined with his masterful skills at self-projection, led him to play with his own name. Which is perhaps unsurprising, as he never really had his own self-identity: he was christened Prince Rogers Nelson after his father’s stage persona, Prince Rogers.

In 1993, Prince famously changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol, causing momentary panic across newspapers and publishing houses who scrambled to find ways to replicate it. Their distress was eased when a way out was found with the description “The Artist Formerly Known as Prince”.

That moniker remained until 2000. But far more important was his equal willingness to shatter norms and conventions in music. His love of songwriting stretched right back to childhood – he penned his first song aged seven – and while he was still a teenager he recorded his first demo tape at Moon’s Studio in Minneapolis, earning himself a contract with Warner Bros.

Over the next 40 years he made 40 albums and won seven Grammy awards in a flood of musical output that even left the artist himself bamboozled. Last year he told the Guardian that he’d decided to dispense with a band and with a huge back library of previous songs because he found it so hard to marshal.

“Tempo, keys, all those things can dictate what song I’m going to play next, you know, as opposed to, ‘Oh, I’ve got to do my hit single now, I’ve got to play this album all the way through,’ or whatever. There’s so much material, it’s hard to choose. It’s hard.”

His breakthrough came with the 1979 album Prince, which hit the top of the Billboard R&B charts and contained the smash singles Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad? and I Wanna Be Your Lover. Dirty Mind (1980) and Controversy (1981) both managed to attract musical admiration but also, as the latter title suggested, provoke a firestorm of criticism for their edgy interplay between religion and sexuality. With every cleverly concocted row, Prince’s star shone brighter.

But it was in 1984 with Purple Rain that he really captured global adulation. Purple Rain was not so much an album and film, it was a cultural phenomenon. The song of the same name, with its first verse dedicated to his father and recorded over a daring 13 minutes in the First Avenue club in Minneapolis, went on to provide the skeleton structure for both album and movie.

Prince was rewarded with 13m sales of the album. The film, featuring a central character called “The Kid” who leans heavily on Prince’s own life story, won him an Oscar for songwriting.

While other artists who cut their teeth in the 70s have settled for repetitive revivals of their past glories, none of that would satisfy Prince. With the passing of the millennium, his creative production and desire to explore new pastures only grew more intense.

In 2007 he performed a 12-minute set at the Super Bowl that has widely been credited as the greatest half-time show ever at the footballing event. Then, from February 2014 to June 2015 he went on a series of Hit N Run tour dates, wreaking havoc across 15 cities for 39 gigs in a little over a year.

Flanked by his band 3rdeyegirl, the Purple One’s guerrilla gigs would be confirmed sometimes no sooner than a few hours before via Twitter. Stopping in at locations from London to Louisville, Paris to Montreal, his epic sets would take place in a litany of shapes and sizes, at jazz clubs and arenas.

Those who witnessed his most intimate performances would have been rewarded, after hours stood in snaking queues, with a greatest hits funk extravaganza, the likes of Let’s Go Crazy, 1999, Little Red Corvette performed so close you could stare into the whites of his eyes. As a result, thousands of fans were given the opportunity to watch the great musician perform a career-spanning set for one last time.

And if all that wasn’t enough, he still found time to fight a running battle with “slave label” Warner Bros, sue bootleggers for $22m, become a Jehovah’s Witness, and in 2010 declare the internet “completely over”. (In such a long and storied career, it is perhaps permissible to make one glaring mistake.)

Barney Hoskyns, author of Prince biography Imp of the Perverse, said Prince was an artist who defied labels and genres. “This was a guy who effortlessly wrote great riffs, grooves and who packaged them in a really distinctive way. He came out of the white midwest, not the black ghetto, so he synthesized a lot of influences.

“There were the key figures, from James Brown to Sly Stone to Jimi Hendrix, but he was as much a rocker as he was an R&B star. His record label, Warner Brothers, started out trying to manage and market him as a late-70s, post-disco soul star. He wasn’t having it. He knew he wanted to define his own musical persona.”

His final shows were last week at the Fox Theater in Atlanta, where a strict no photos or video rule was in place for two consecutive sets. Billed as the Piano and a Microphone tour, Prince played solo at a purple grand piano.

Before concluding with Kiss, his third encore performance in the earlier show, Prince sang Heroes in tribute to David Bowie, who died in January. Back on stage within the hour for his final late night show, he ended with three encores and a medley of Purple Rain, The Beautiful Ones and Diamonds and Pearls.

When the Guardian visited him in Paisley Park last year, he described spending the previous night just playing to himself for three hours witPrince, superstar and pioneer of American music, dies aged 57

“I just couldn’t stop. That’s what you want. Transcendence. When that happens … Oh, boy.”

His breakthrough came with the 1979 album Prince, which hit the top of the Billboard R&B charts and contained the smash singles Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad? and I Wanna Be Your Lover. Dirty Mind (1980) and Controversy (1981) both managed to attract musical admiration but also, as the latter title suggested, provoke a firestorm of criticism for their edgy interplay between religion and sexuality. With every cleverly concocted row, Prince’s star shone brighter.

But it was in 1984 with Purple Rain that he really captured global adulation. Purple Rain was not so much an album and film, it was a cultural phenomenon. The song of the same name, with its first verse dedicated to his father and recorded over a daring 13 minutes in the First Avenue club in Minneapolis, went on to provide the skeleton structure for both album and movie.

Prince was rewarded with 13m sales of the album. The film, featuring a central character called “The Kid” who leans heavily on Prince’s own life story, won him an Oscar for songwriting.

While other artists who cut their teeth in the 70s have settled for repetitive revivals of their past glories, none of that would satisfy Prince. With the passing of the millennium, his creative production and desire to explore new pastures only grew more intense.

In 2007 he performed a 12-minute set at the Super Bowl that has widely been credited as the greatest half-time show ever at the footballing event. Then, from February 2014 to June 2015 he went on a series of Hit N Run tour dates, wreaking havoc across 15 cities for 39 gigs in a little over a year.

Flanked by his band 3rdeyegirl, the Purple One’s guerrilla gigs would be confirmed sometimes no sooner than a few hours before via Twitter. Stopping in at locations from London to Louisville, Paris to Montreal, his epic sets would take place in a litany of shapes and sizes, at jazz clubs and arenas.

Those who witnessed his most intimate performances would have been rewarded, after hours stood in snaking queues, with a greatest hits funk extravaganza, the likes of Let’s Go Crazy, 1999, Little Red Corvette performed so close you could stare into the whites of his eyes. As a result, thousands of fans were given the opportunity to watch the great musician perform a career-spanning set for one last time.

And if all that wasn’t enough, he still found time to fight a running battle with “slave label” Warner Bros, sue bootleggers for $22m, become a Jehovah’s Witness, and in 2010 declare the internet “completely over”. (In such a long and storied career, it is perhaps permissible to make one glaring mistake.)

Barney Hoskyns, author of Prince biography Imp of the Perverse, said Prince was an artist who defied labels and genres. “This was a guy who effortlessly wrote great riffs, grooves and who packaged them in a really distinctive way. He came out of the white midwest, not the black ghetto, so he synthesized a lot of influences.

“There were the key figures, from James Brown to Sly Stone to Jimi Hendrix, but he was as much a rocker as he was an R&B star. His record label, Warner Brothers, started out trying to manage and market him as a late-70s, post-disco soul star. He wasn’t having it. He knew he wanted to define his own musical persona.”

His final shows were last week at the Fox Theater in Atlanta, where a strict no photos or video rule was in place for two consecutive sets. Billed as the Piano and a Microphone tour, Prince played solo at a purple grand piano.

Before concluding with Kiss, his third encore performance in the earlier show, Prince sang Heroes in tribute to David Bowie, who died in January. Back on stage within the hour for his final late night show, he ended with three encores and a medley of Purple Rain, The Beautiful Ones and Diamonds and Pearls.

When the Guardian visited him in Paisley Park last year, he described spending the previous night just playing to himself for three hours witPrince, superstar and pioneer of American music, dies aged 57

“I just couldn’t stop. That’s what you want. Transcendence. When that happens … Oh, boy.”

Alexis Petridis

Thursday 12 November 2015

In 1985, Prince released a single called Paisley Park, the first to be taken from his psychedelic opus, Around the World In a Day. It’s one of several Prince songs that describe a location that’s a kind of mystical utopia.

Paisley Park, the lyrics aver, is filled with laughing children on see-saws and “colourful people” with expressions that “speak of profound inner peace”, whatever they look like. “Love is the colour this place imparts,” it continues. “There aren’t any rules in Paisley Park.”

It’s all a bit difficult to square with Paisley Park, the vast studio complex Prince built a couple of years later. It sits behind a chainlink fence in the nondescript Minnesota suburb of Chanhassen, and there’s no getting around the fact that, from the outside at least, it looks less like a mystical utopia, more like a branch of Ikea.

Inside, however, it looks almost exactly like you’d imagine a huge recording complex owned by Prince would look. There is a lot of purple. The symbol that represented Prince’s name for most of the 90s is everywhere: hanging from the ceiling, painted on speakers and the studio’s mixing desks, illuminating one room in the form of a neon sign.

There is something called the Galaxy Room, apparently intended for meditation: it is illuminated entirely by ultraviolet lights and has paintings of planets on the walls. There are murals depicting the studio’s owner, never a man exactly crippled by modesty.

And there are two full-sized live-music venues: a vast, hangar-like space that also features a food concession – form an orderly queue for Funky House Party In Your Mouth Cheesecake ($4) – and a smaller room decked out to look like a nightclub. I am currently on the stage of the latter, along with four other representatives of the European press.

We are literally sitting at Prince’s feet: feet, it’s perhaps worth noting, that are wearing a pair of flip-flops with huge platform soles teamed with socks. The socks and flip-flops are white, as is the rest of his outfit: skinny flared trousers, a T-shirt with long sleeves, also flared. As skinny as a teenager, sporting an afro and almost unnecessarily handsome at 57 years old, Prince looks flatly amazing, exuding ineffable cool and panache while wearing clothes that would make anyone else look like a ninny is just one among his panoply of talents.

We are seated at his feet because we are supposed to be asking Prince questions: we’ve been summoned to Paisley Park at short notice, apparently because Prince “had a brainstorm in the middle of the night, two nights ago” and decided this was the best way to announce a forthcoming European tour.

First, there was a tour of the studio accompanied by Trevor Guy, who works for Prince’s record label NPG: he’s friendly, effusive about his boss’s talents and a little evasive when someone asks him whereabouts in Minneapolis Prince actually lives. (“He doesn’t live here. I don’t know where he lives.”)

Then we were told we were getting a treat, which turned out to be listening to some cover versions Prince’s current protege, Andy Allo, recorded with the man himself on guitar. While we’re listening to Andy Allo sing Roxy Music’s More Than This, Prince suddenly appears on the stage and beckons us over.

The dates haven’t actually been confirmed yet, but the concept has: he’s going to perform solo, playing the piano, in a succession of theatres. “Well, I’m not one to get bad reviews,” he deadpans.

“So I’m doing it to challenge myself, like tying one hand behind my back, not relying on the craft that I’ve known for 30 years. I won’t know what songs I’m going to do when I go on stage, I really won’t. I won’t have to, because I won’t have a band. Tempo, keys, all those things can dictate what song I’m going to play next, you know, as opposed to, ‘Oh, I’ve got to do my hit single now, I’ve got to play this album all the way through,’ or whatever. There’s so much material, it’s hard to choose. It’s hard. So that’s what I’d like to do.”

Prince, it has to be said, is proving the very model of softly spoken charm. He’s also wryly funny on topics ranging from his songwriting (“I have to do it to clear my head, it’s like … shaking an Etch a Sketch”) to the activist Rachael Dolezal, or as he puts it, “that lady who said she was black even though she was white”, to his famous 2010 pronouncement that “the internet is completely over”.

“What I meant was that the internet was over for anyone who wants to get paid, and I was right about that,” he says. “Tell me a musician who’s got rich off digital sales. Apple’s doing pretty good though, right?”

It’s all a far cry from the days when he refused to talk to the press, disparaged them in song – “Take a bath, hippies!” he snapped in 1982’s All The Critics Love U In New York – or dismissed them “mamma-jammas wearing glasses and an alligator shirt behind a typewriter”.

“Oh, I love critics,” he smiles. “Because they love me. It’s not a joke. They care. See, everybody knows when somebody’s lazy, and now, with the internet, it’s impossible for a writer to be lazy because everybody will pick up on it. In the past, they said some stuff that was out of line, so I just didn’t have anything to do with them. Now it gets embarrassing to say something untrue, because you put it online and everyone knows about it, so it’s better to tell the truth.”

Nevertheless, it’s turning out to be harder to ask questions than you might think. Prince is seated at a microphone behind a keyboard, which he keeps playing. This is quite disconcerting: if he doesn’t like a question, he strikes up with the theme from The Twilight Zone and shakes his head. At one point, he presses a button on the keyboard and the intro to his legendary 1988 hit Sign o’ the Times booms out of the PA.

He looks at me. “You wanna do this?” he says. I look back at him aghast: there are doubtless things I want to do less than sing Prince’s legendary 1988 hit Sign o’ the Times in front of Prince, but at this exact moment I’m struggling to think of any. For one thing, Prince is, by common consent, the one bona-fide, no-further-questions musical genius that 80s pop produced; a man who can play pretty much any instrument he choses, possessed of a remarkable voice that can still leap effortlessly from baritone to falsetto.

I, on the other hand, am a deeply unfunky Englishman with no discernible musical ability: the sound of my singing voice can ruin your day. For another, I’m a journalist, and thus aware that among Prince’s panoply of talents lies a nonpareil ability to screw with journalists. Rumours abound of him demanding hacks dance in front of him. Only if their gyrations are deemed sufficiently funky do they get face time.

A recent visitor to Paisley Park found himself standing in the studio having a telephone conversation with Prince, who, it later transpired, was standing in the next room all along. The novelist Matt Thorne, author of a 500-page book that stands as the definitive work on Prince’s oeuvre, tells a story of pursuing him for an interview, and being invited to attend a gig in New York.

Midway through a guitar solo, Prince spotted Thorne in the audience, walked over, whispered: “How about that interview?” then ran off, still soloing: Thorne never heard from him again. So I shake my head and say no: for a mercy, Prince shrugs and turns the music off and we plough on, albeit a little awkwardly.