Frank Black

5 January 2015

Mention Blake Edwards and most people will think of the Pink

Panther films, a series that started with a nod to the screwball comedies of

the thirties and forties and ended up as a sort of bloated, self-indulgent

cash-cow for star and director, both of whom struggled to show their true worth

in their later films, though both did succeed: Sellers with the intelligently witty Being

There (1979) and Edwards with the sophisticated and genuinely funny

Victor/Victoria (1982) – though he misguidedly returned to the Panther

franchise three times after Sellers’ early death.

Beyond the Panther films, his name conjures up images of

Audrey Hepburn in a black figure-hugging dress, smoking sexily with a long

cigarette holder in his adaptation of

Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), but Edwards had a strange

career. He made a name for himself with the smart private eye show, Peter Gunn,

which ran from 1958-1961. Gunn was an upmarket PI, listening to cool West Coast

jazz (the score was by Edwards’ frequent sparring partner, Henry Mancini),

charging a standard fee of $1000, some twenty years before Jim Rockford was

asking for only $200 a day plus expenses. This wasn’t Edwards’ first foray into

this territory; in fact, he developed the Gunn character from his own creation,

Richard Diamond, Private Investigator (starring Dick Powell in the radio

version (1949-53) and David Janssen on television (1957-1960)).

While his career may be dominated by lighter films, this more

dramatic streak runs through works like Mr Cory (1957), Days of Wine and Roses

(1962), his excellent elegiac Western, Wild Rovers (1971), The Carey Treatment (1972)

and Experiment in Terror (1962).

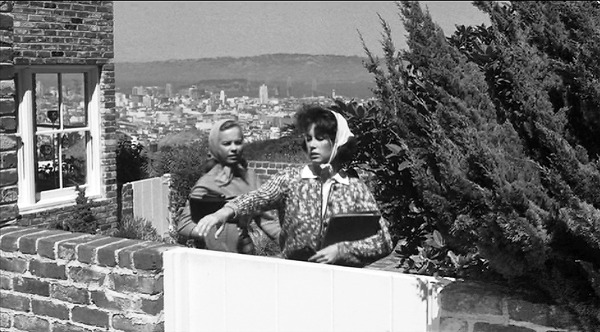

The latter is a neo-noirish thriller set in San Francisco, making

excellent use of real locations around the city, not least The Clarendon

Heights/Twin Peaks area where the victim/heroine lives and is watched both by

the killer and the FBI.

Based on the book, Operation Terror, by Gordon and Mildred

Gordon, who also wrote the screenplay, it concerns bank teller Kelly Sherwood (Lee

Remick), stalked by an asthmatic killer, Red Lynch (Ross Martin), who –

initially at least – is unidentified and who threatens to kill her and her

teenage sister Toby (a young Stephanie Powers), unless she helps him rob the

bank she works at.

Despite the fact he knows she has been in contact with FBI

agent John Ripley (Glenn Ford), he continues to stalk and torment her until his

identity is discovered and the story climaxes in a shootout in a deserted Candlestick

Park

Here’s the beautifully constructed opening sequence, atmospherically shot by Philip Lathrop and moodily scored by Henry Mancini:

Purists might scoff at this being classified as noir, but it

is a thematically dark film as well as one that liberally cops various visual

motifs from the genre, like the shadows of blinds that fall across Ford in his

office where he meets a woman who may or

may not be about to set him up, or the garage bathed in chiaroscuro lighting where Kelly first encounters Lynch, a scene which Edwards carefully

uses to ratchet up the tension.

Mancini’s jazzy score is used subtly to build up an ominous

sense of fear, complementing Edward and Northrup’s visual techniques, whether

carefully constructed mise-en-scene, intense close-ups, use of deep focus or abrupt

transitions to jar the audience.

However, certain scenes stand out, most notably the opening in Sherwood’s

garage with lighting and canted close-ups leading the audience to expect an assault that is replaced by cold threatening coercion, and

the almost surreal scene in Nancy’s (Patricia Huston) apartment, where it is gradually

revealed that she shares it with what seem to be hundreds of unclothed

mannequins, which are later used effectively to ‘reveal’ her murdered body

after she has tried to help Sherwood by going to the FBI.

Lynch’s character is given a little depth when it is

revealed that an Asian-American woman he has been dating will not inform on him

because he has been helping her financially because her son is in hospital –

though this is not an aspect the film dwells on too much.

This is a stylish, well-paced gripping late noir (or early neo-noir – argue among yourselves), beautifully shot with excellent performances, especially Remick and the understated (and often undervalued) Ford.

This is a stylish, well-paced gripping late noir (or early neo-noir – argue among yourselves), beautifully shot with excellent performances, especially Remick and the understated (and often undervalued) Ford.

_630_331_90.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment