Friday, 30 January 2015

Thursday, 29 January 2015

Last night's set lists

At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

Dead Flowers

Wagon Wheel

Need Your Love So Bad

You Better Move On

Da Elderly: -

There Stands The Glass

Mother's Lament

Helpless

I Don't Want To Talk About It

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Price Of Love

Walk Right Back

So Sad (To Watch Good Love Go Bad)

He'll Have To Go

Well....it was just like the old times at The Habit open mic, on a miserable night outside; the place was packed almost from the start, with loads of players and punters. By the time The Elderly Brothers hit the mic it was close to midnight and we managed to play our set without the book (and a safety net)!! Beer and Fireballs flowed and the after-show unplugged session even had some folks dancing. I repeat....it was just like the old times.

Ron Elderly: -

Dead Flowers

Wagon Wheel

Need Your Love So Bad

You Better Move On

Da Elderly: -

There Stands The Glass

Mother's Lament

Helpless

I Don't Want To Talk About It

The Elderly Brothers: -

The Price Of Love

Walk Right Back

So Sad (To Watch Good Love Go Bad)

He'll Have To Go

Well....it was just like the old times at The Habit open mic, on a miserable night outside; the place was packed almost from the start, with loads of players and punters. By the time The Elderly Brothers hit the mic it was close to midnight and we managed to play our set without the book (and a safety net)!! Beer and Fireballs flowed and the after-show unplugged session even had some folks dancing. I repeat....it was just like the old times.

Monday, 26 January 2015

Bob Dylan - Shadows in the Night review

Dylan's 'Shadows in the Night' illuminates American standards

Bob Dylan upends expectations once again with his 'Shadows in the Night' collection of American standards

Randall Roberts

http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/la-et-ms-dylan-shadows-review-20150126-column.html

Bob Dylan upends expectations once again with his 'Shadows in the Night' collection of American standards

Randall Roberts

Los Angeles Times

26 January 2015

Call them standards if you must — imagine dusty old classics of the so-called Great American Songbook. But as interpreted by Bob Dylan, more accurate is to consider the entirety of "Shadows in the Night" as a gathering of meditations, or a booklet of hymns, or a selection of reveries.

Ten songs, 34 minutes, a soaring lifetime's worth of emotion conveyed with the fearlessness of a cliff diver spinning flips and risking belly flops in the open air — that's Dylan and his band on the graceful, often breathtaking "Shadows." The record comes out Feb. 3.

Strikingly unadorned and as emotionally raw as anything in the artist's canon, Dylan's new studio album is rich with moaning pedal steel lines and tonal whispers that drift in and out of measures. Guided by bassist Tony Garnier's liquid lines, "Shadows" is an exercise in precision, each syllable essential, each measure evenly weighted. Absent are piano, overdubs, all but the most minimal percussion or any lyric written by Dylan himself. And it's as slow as molasses.

Rather, for "Shadows," the 73-year-old artist gathered his longtime band into Studio A at Capitol Studios in Hollywood to celebrate the artfully penned lyric and melody. Resurrecting works, many obscure, written or cowritten in the decades between the 1920s and '60s by composers including Rodgers & Hammerstein, Irving Berlin, Matt Dennis & Tom Adair, Frank Sinatra and Buddy Kaye, the album is a celebration of the craft and enduring power of a seamless ballad.

A random selection of lines tells the story: Where is my happy ending? Where are you? Since you went away the days grow long. Full moon and empty arms. I'm a fool to love you. Take me back, I need you. What'll I do when you are far away and I am blue? I'm sentimental, so I walk in the rain. I've got some habits even I can't explain.

Songs of lovers gone, of vanishing emotions, of fading years and stubborn habits, of isolation, unanswered prayers and never-ending hope — you can feel the emptiness. The studio comfortably fits 50 musicians, but this session was tight: Dylan circled by the five who tour with him: Garnier, Stu Kimball (rhythm guitar), Donnie Herron (pedal steel, lap steel), Charlie Sexton (lead guitar) and George Receli (drums, percussion). The occasional muted brass section washes through.

Recording the songs in the order in which they appear on the album, the artist didn't even use headphones to monitor the mix. Rather, he listened to the experts around him, spiriting intimate takes on songs about autumn leaves, enchanted evenings and an ambivalent sun spinning around. So intimate is the recording that vague hints of Dylan's breath can be heard at key moments. The occasional shuffle of a lyric sheet. A little inhale at the end of a lap steel line during "What'll I Do."

The result is akin to Willie Nelson's "Stardust," Chet Baker's late-period "Let's Get Lost" recordings or Jimmy Scott's miraculous post-retirement comeback, "All the Way." If there's a connector, it's that all the songs on "Shadows" were interpreted at one time or another by Frank Sinatra. But this certainly isn't a tribute per se to that swinging stylist.

That's a relief, as Dylan is obviously no Sinatra. His voice raw, pitchy and quivering, Dylan croons his way through elegantly crafted songs with seeming disinterest in flawless takes or perfect pitch. Yet it's profound, thematically devastating and so well curated as to feel essential.

"Shadows in the Night" is an album that's best appreciated when heard with intention, while sitting still, with volume and focus. It's Dylan upending expectations once again, another left turn in a career filled with them, sharing his wisdom and defining himself through the lines of others. He's done that both as a historian and a thief of American music, playing with context and blurring intentions in innumerable songs.

In that sense, the album's closest companions in his repertoire are two equally intimate albums of cover songs from the early '90s that helped further define him, "Good as I Been to You" and "World Gone Wrong." Those too were minimalist Dylan — just him and guitar. They featured the artist's takes on a different brand of American song: haggard old blues songs and murder ballads. Both explored love and death through songs of violent betrayal. Then in his early 50s, Dylan still burned with feral passion, singing of "blood in my eyes" for a lover, of a life cut too short in "Delia." For "Shadows," that passion is supplanted with equanimity and hard-earned wisdom.

In fact, if there's an underlying philosophy to "Shadows," Dylan hints at it in his only interview in regards to the record. Strategically given to AARP magazine, he offered thoughts on aging and creative expression: "Passion is a young man's game," he said. "Young people can be passionate. Older people gotta be more wise. I mean, you're around awhile, you leave certain things to the young. Don't try to act like you're young. You could really hurt yourself."

Call them standards if you must — imagine dusty old classics of the so-called Great American Songbook. But as interpreted by Bob Dylan, more accurate is to consider the entirety of "Shadows in the Night" as a gathering of meditations, or a booklet of hymns, or a selection of reveries.

Ten songs, 34 minutes, a soaring lifetime's worth of emotion conveyed with the fearlessness of a cliff diver spinning flips and risking belly flops in the open air — that's Dylan and his band on the graceful, often breathtaking "Shadows." The record comes out Feb. 3.

Strikingly unadorned and as emotionally raw as anything in the artist's canon, Dylan's new studio album is rich with moaning pedal steel lines and tonal whispers that drift in and out of measures. Guided by bassist Tony Garnier's liquid lines, "Shadows" is an exercise in precision, each syllable essential, each measure evenly weighted. Absent are piano, overdubs, all but the most minimal percussion or any lyric written by Dylan himself. And it's as slow as molasses.

Rather, for "Shadows," the 73-year-old artist gathered his longtime band into Studio A at Capitol Studios in Hollywood to celebrate the artfully penned lyric and melody. Resurrecting works, many obscure, written or cowritten in the decades between the 1920s and '60s by composers including Rodgers & Hammerstein, Irving Berlin, Matt Dennis & Tom Adair, Frank Sinatra and Buddy Kaye, the album is a celebration of the craft and enduring power of a seamless ballad.

A random selection of lines tells the story: Where is my happy ending? Where are you? Since you went away the days grow long. Full moon and empty arms. I'm a fool to love you. Take me back, I need you. What'll I do when you are far away and I am blue? I'm sentimental, so I walk in the rain. I've got some habits even I can't explain.

Songs of lovers gone, of vanishing emotions, of fading years and stubborn habits, of isolation, unanswered prayers and never-ending hope — you can feel the emptiness. The studio comfortably fits 50 musicians, but this session was tight: Dylan circled by the five who tour with him: Garnier, Stu Kimball (rhythm guitar), Donnie Herron (pedal steel, lap steel), Charlie Sexton (lead guitar) and George Receli (drums, percussion). The occasional muted brass section washes through.

Recording the songs in the order in which they appear on the album, the artist didn't even use headphones to monitor the mix. Rather, he listened to the experts around him, spiriting intimate takes on songs about autumn leaves, enchanted evenings and an ambivalent sun spinning around. So intimate is the recording that vague hints of Dylan's breath can be heard at key moments. The occasional shuffle of a lyric sheet. A little inhale at the end of a lap steel line during "What'll I Do."

The result is akin to Willie Nelson's "Stardust," Chet Baker's late-period "Let's Get Lost" recordings or Jimmy Scott's miraculous post-retirement comeback, "All the Way." If there's a connector, it's that all the songs on "Shadows" were interpreted at one time or another by Frank Sinatra. But this certainly isn't a tribute per se to that swinging stylist.

That's a relief, as Dylan is obviously no Sinatra. His voice raw, pitchy and quivering, Dylan croons his way through elegantly crafted songs with seeming disinterest in flawless takes or perfect pitch. Yet it's profound, thematically devastating and so well curated as to feel essential.

"Shadows in the Night" is an album that's best appreciated when heard with intention, while sitting still, with volume and focus. It's Dylan upending expectations once again, another left turn in a career filled with them, sharing his wisdom and defining himself through the lines of others. He's done that both as a historian and a thief of American music, playing with context and blurring intentions in innumerable songs.

In that sense, the album's closest companions in his repertoire are two equally intimate albums of cover songs from the early '90s that helped further define him, "Good as I Been to You" and "World Gone Wrong." Those too were minimalist Dylan — just him and guitar. They featured the artist's takes on a different brand of American song: haggard old blues songs and murder ballads. Both explored love and death through songs of violent betrayal. Then in his early 50s, Dylan still burned with feral passion, singing of "blood in my eyes" for a lover, of a life cut too short in "Delia." For "Shadows," that passion is supplanted with equanimity and hard-earned wisdom.

In fact, if there's an underlying philosophy to "Shadows," Dylan hints at it in his only interview in regards to the record. Strategically given to AARP magazine, he offered thoughts on aging and creative expression: "Passion is a young man's game," he said. "Young people can be passionate. Older people gotta be more wise. I mean, you're around awhile, you leave certain things to the young. Don't try to act like you're young. You could really hurt yourself."

The secret Sinatra past of Bob Dylan's new album

Gustavo Turner

Los Angeles Times

24 January 2015

Bob Dylan has a new album coming out Feb. 3, "Shadows in the Night," a collection of pop songs about romance, heartbreak and other existential themes written by other songwriters.

But whatever you call this labor-of-love project, there's one thing Bob Dylan does not want you to call it: his "Sinatra covers album."

These are old songs, written between the early 1920s and the early 1960s, some of which have become bona fide jazz standards ("Autumn Leaves"), others of which were minor hits when they were first recorded ("Full Moon and Empty Arms"), and there's even the odd gem ("Stay With Me") that has been overlooked by audiences since its first appearance on an obscure single.

All these songs have one thing in common: They were recorded by Frank Sinatra at some point (in some cases, several points) in his career.

"I don't see myself as covering these songs in any way," Dylan said in a statement last December. "They've been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What me and my band are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day."

In a way, Dylan is treating the massive Sinatra catalog as an open bazaar from where he has decided to rearrange and reinterpret specific areas to create a new, wholly Dylanesque work. It's the same process he applied to the folk standard canon in his first album in 1961 and the kind of artistic practice he has continued in his forays into fine art, where he works in the same appropriation and resignification field as artists like Richard Prince.

"In folk and jazz, quotation is a rich and enriching tradition," he told Rolling Stone magazine in 2012, speaking about his use of lines from Civil War poet Henry Timrod and others in some of his recent songs. "As far as [...] Timrod is concerned, have you even heard of him? Who's been reading him lately? And who's pushed him to the forefront? Who's been making you read him?"

The same could be said of the following Sinatra-related songs, which will surely be given new life into the 21st century by Dylan's selection process:

"I'm a Fool to Want You" (Sinatra, Wolf, Herron): First recorded by Sinatra in 1951, with an arrangement by Axel Stordahl, in New York for Columbia Records. It was B-side to novelty single "Mama Will Bark" (with Dagmar, a busty chorus girl and early TV starlet). It's a rare songwriting credit for Sinatra, who's much better known as an interpreter of others' material. "Frank changed part of the lyric, and made it say what he felt when he was doing it," explained cowriter Joel Herron in the book "Frank Sinatra: An American Legend." "We said, 'He's gotta be on this song!' and we invited him as cowriter." At the time the singer had left his first wife Nancy to be together with Ava Gardner, whom he was hoping to marry after his divorce had been finalized. He recorded a second version in 1957 in Hollywood at the legendary Capitol Tower, this time arranged by Gordon Jenkins. It was released on "Where Are You?," his 1957 album of "suicide songs" (Sinatra's term for his concept albums about masculine loneliness) released by Capitol. In fact, four out of 10 songs on Dylan's "Shadows in the Night," also recorded in Hollywood's Capitol Tower, were songs Sinatra recorded for "Where Are You?" After Sinatra's recording, "I'm a Fool to Want You" became a popular song with other interpreters, and it was also recorded by Billie Holiday (for 1958's "Lady in Satin," a Sinatra favorite), Dinah Washington, Billy Eckstine, Chet Baker, Peggy Lee, Tom Jones, Elvis Costello and many others.

"The Night We Called It a Day" (Dennis, Adair): Originally published in 1941, Sinatra also recorded this in 1957 at the Capitol Tower for "Where Are You?," arranged by Gordon Jenkins. There are other notable pop versions by Chet Baker, June Christy and Doris Day, and a great jazz arrangement by Milt Jackson and John Coltrane. Trivia fact: The song gives its original title to a bizarre 2003 Australian movie (also know as "All the Way") with Dennis Hopper playing Frank Sinatra and Melanie Griffith playing the singer's fourth (and final) wife, Barbara.

"Stay With Me" (Moross, Jerome): Originally known as "Stay With Me (Main Theme from 'The Cardinal')" and featured in the soundtrack of a 1963 social melodrama directed by Otto Preminger, this is the real obscure piece in the set. It came out on Sinatra's own label, Reprise, in 1964 as a single, but only stayed three weeks on the Billboard charts, peaking at an unimpressive No. 81. (It also turned up a year later on an odds-and-ends Reprise album, "Sinatra '65"). It was recorded in December 1963 at United Western Recorders in Hollywood, with Don Costa arranging and conducting. The week "Stay With Me" peaked at 81 (Feb. 1, 1964) was right in the heart of Beatlemania and "I Want to Hold Your Hand" ruled the airwaves. At the time, Dylan was between "The Times They Are-a-Changing" (which had just been released) and "Another Side of Bob Dylan." The passionate, epic "Stay With Me" wouldn't have made a strong impression on him at the time: Dylan had just embarked on a legendary, pot-fueled cross-country trip with his buddies, where he would write youth-culture classics like "Chimes of Freedom."

"Autumn Leaves" (Mercer, Kosma, Prevert): Yet another song recorded by Sinatra for "Where Are You?" in 1957 at Capitol with arrangements by Gordon Jenkins, in the same session as "The Night We Called It a Day." "Autumn Leaves," a jazz standard, was originally written in 1945 in France by Hungarian composer Joseph Kosma and poet Jacques Prevert as "Les Feuilles Mortes" ("Dead Leaves"). Sublime lyricist Johnny Mercer wrote English words for it in 1947. There are many, many versions of this song, so we'll just note a few: Jo Stafford's big pop hit, an unusual version in Japanese by Nat King Cole, bilingual versions in French and English by Edith Piaf (1950), and Iggy Pop's 2009 cover for his strange Francophile project "Préliminaires." Jerry Lee Lewis, strangely enough given his manic persona, has had a moving version of "Autumn Leaves" as part of his extensive repertoire for decades (there's a YouTube video of Lewis performing the song in 1971).

"Why Try to Change Me Now" (Coleman, McCarthy): Sinatra recorded this twice. The first version, from 1952 (arranged by Percy Faith), was his last recording for Columbia Records and many interpreted the lyrics as a kiss-off to the company. The second recording is from 1959's "No One Cares," another Jenkins-arranged album of "suicide songs" and a thematic sequel of sorts to Dylan favorite "Where Are You?" The song was cowritten by Broadway legend Cy Coleman, of "Sweet Charity" fame. An outstanding modern version was recorded by Fiona Apple for "The Best Is Yet to Come" a 2009 multi-artist tribute to Coleman. Check out the live version at L.A.'s Largo.

"Some Enchanted Evening" (Rodgers and Hammerstein): One of the showstoppers from 1949's hit musical "South Pacific," of course, Sinatra recorded it three times, first when the song was fresh, for a 1949 Columbia single arranged by Axel Stordahl, which didn't sell as well as contemporary versions by Perry Como and Bing Crosby. Sinatra rerecorded it in 1963 with Nelson Riddle as part of the "Reprised Musical Repertory Theater" series of albums based on Broadway musicals that he recorded with showbiz friends. He revived it in the autumn of his years for the H.B. Barnum-led 1967 sessions for "The World We Knew." Other versions? Take your pick, as it's been done by everyone from Art Garfunkel to Harry Connick Jr. to any number of sentimental karaoke drunks around the world.

"Full Moon and Empty Arms" (Rachmaninoff, Kaye and Mossman): Yes, Rachmaninoff as in the famous Russian composer, from whose Piano Concerto No. 2 Kaye and Mossman adapted the melody in 1945. Sinatra had a minor hit on Columbia with it, and it was later done by Eddie Fisher and Sarah Vaughan. It was the track chosen by Dylan to give a sneak peek into the project back in May 2014.

"Where Are You?" (Adamson, McHugh): The title song from 1957 heartbreak concept album "Where Are You?" (and by this point, it should be clear, one of the inspirations of Dylan's "Shadows in the Night"). By the time Sinatra got around to recording it the song was 20 years old, originating in the 1937 film "Top of the Town." The early hit version was by Mildred Bailey in the 1930s, but Sinatra made it his. There are many other good versions, including those by Shirley Bassey, Dinah Washington and this writer's favorite songstress, Julie London. Aretha Franklin recorded a moving rendition in 1963 during her unfairly maligned stint at Columbia Records as a jazz and pop singer.

"What'll I Do" (Berlin): The oldest song on the set, written by Irving Berlin in the early 1920s for a Broadway revue. Jazzman Paul Whiteman had a hit with it in 1924. Sinatra recorded it twice: in 1947 for Columbia with Axel Stordahl and in 1962 for Reprise with Gordon Jenkins. The 1962 version was released on "All Alone," Sinatra's update for his own label, Reprise, of his famous "suicide songs" concept albums for Capitol in the 1950s. The song remained a popular standard for decades and there are good versions by Chet Baker (Dylan and Baker seem to share an affinity for the same torch songs), Lena Horne, Julie London, Sarah Vaughan, Cher and Harry Nilsson. "What'll I Do" was also used by Nelson Riddle as the theme for his score for the 1974 version of "The Great Gatsby" (the one with Robert Redford and Mia Farrow).

"That Lucky Old Sun" (Smith, Gillespie): "Shadows in the Night" closes with the most soulful of the songs Dylan selected. Composed in 1949 as a kind of late-era spiritual/work song, it was recorded by Louis Armstrong, but Frankie Laine had the hit. Sinatra did his version when the song was new, but Laine's became the definitive rendition of 1949 (and a palpable influence on singers who were coming of age at the time like Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash). Jerry Lee Lewis revved it up as a Sun recording, and it was later adopted as a proto-soul standard by Sam Cooke, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin (also during the Columbia years). More recently, Willie Nelson recorded a crystalline version for 1976's "The Sound in Your Mind" (included now as a bonus track to Willie's "Stardust," which Dylan told AARP was a direct influence on "Shadows in the Night") and in 2007 became the centerpiece of a song cycle about California by none other than Brian Wilson.

http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/posts/la-et-ms-dylan-sinatra-covers-20150123-story.html#page=1

Bob Dylan has a new album coming out Feb. 3, "Shadows in the Night," a collection of pop songs about romance, heartbreak and other existential themes written by other songwriters.

But whatever you call this labor-of-love project, there's one thing Bob Dylan does not want you to call it: his "Sinatra covers album."

These are old songs, written between the early 1920s and the early 1960s, some of which have become bona fide jazz standards ("Autumn Leaves"), others of which were minor hits when they were first recorded ("Full Moon and Empty Arms"), and there's even the odd gem ("Stay With Me") that has been overlooked by audiences since its first appearance on an obscure single.

All these songs have one thing in common: They were recorded by Frank Sinatra at some point (in some cases, several points) in his career.

"I don't see myself as covering these songs in any way," Dylan said in a statement last December. "They've been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What me and my band are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day."

In a way, Dylan is treating the massive Sinatra catalog as an open bazaar from where he has decided to rearrange and reinterpret specific areas to create a new, wholly Dylanesque work. It's the same process he applied to the folk standard canon in his first album in 1961 and the kind of artistic practice he has continued in his forays into fine art, where he works in the same appropriation and resignification field as artists like Richard Prince.

"In folk and jazz, quotation is a rich and enriching tradition," he told Rolling Stone magazine in 2012, speaking about his use of lines from Civil War poet Henry Timrod and others in some of his recent songs. "As far as [...] Timrod is concerned, have you even heard of him? Who's been reading him lately? And who's pushed him to the forefront? Who's been making you read him?"

The same could be said of the following Sinatra-related songs, which will surely be given new life into the 21st century by Dylan's selection process:

"I'm a Fool to Want You" (Sinatra, Wolf, Herron): First recorded by Sinatra in 1951, with an arrangement by Axel Stordahl, in New York for Columbia Records. It was B-side to novelty single "Mama Will Bark" (with Dagmar, a busty chorus girl and early TV starlet). It's a rare songwriting credit for Sinatra, who's much better known as an interpreter of others' material. "Frank changed part of the lyric, and made it say what he felt when he was doing it," explained cowriter Joel Herron in the book "Frank Sinatra: An American Legend." "We said, 'He's gotta be on this song!' and we invited him as cowriter." At the time the singer had left his first wife Nancy to be together with Ava Gardner, whom he was hoping to marry after his divorce had been finalized. He recorded a second version in 1957 in Hollywood at the legendary Capitol Tower, this time arranged by Gordon Jenkins. It was released on "Where Are You?," his 1957 album of "suicide songs" (Sinatra's term for his concept albums about masculine loneliness) released by Capitol. In fact, four out of 10 songs on Dylan's "Shadows in the Night," also recorded in Hollywood's Capitol Tower, were songs Sinatra recorded for "Where Are You?" After Sinatra's recording, "I'm a Fool to Want You" became a popular song with other interpreters, and it was also recorded by Billie Holiday (for 1958's "Lady in Satin," a Sinatra favorite), Dinah Washington, Billy Eckstine, Chet Baker, Peggy Lee, Tom Jones, Elvis Costello and many others.

"The Night We Called It a Day" (Dennis, Adair): Originally published in 1941, Sinatra also recorded this in 1957 at the Capitol Tower for "Where Are You?," arranged by Gordon Jenkins. There are other notable pop versions by Chet Baker, June Christy and Doris Day, and a great jazz arrangement by Milt Jackson and John Coltrane. Trivia fact: The song gives its original title to a bizarre 2003 Australian movie (also know as "All the Way") with Dennis Hopper playing Frank Sinatra and Melanie Griffith playing the singer's fourth (and final) wife, Barbara.

"Stay With Me" (Moross, Jerome): Originally known as "Stay With Me (Main Theme from 'The Cardinal')" and featured in the soundtrack of a 1963 social melodrama directed by Otto Preminger, this is the real obscure piece in the set. It came out on Sinatra's own label, Reprise, in 1964 as a single, but only stayed three weeks on the Billboard charts, peaking at an unimpressive No. 81. (It also turned up a year later on an odds-and-ends Reprise album, "Sinatra '65"). It was recorded in December 1963 at United Western Recorders in Hollywood, with Don Costa arranging and conducting. The week "Stay With Me" peaked at 81 (Feb. 1, 1964) was right in the heart of Beatlemania and "I Want to Hold Your Hand" ruled the airwaves. At the time, Dylan was between "The Times They Are-a-Changing" (which had just been released) and "Another Side of Bob Dylan." The passionate, epic "Stay With Me" wouldn't have made a strong impression on him at the time: Dylan had just embarked on a legendary, pot-fueled cross-country trip with his buddies, where he would write youth-culture classics like "Chimes of Freedom."

"Autumn Leaves" (Mercer, Kosma, Prevert): Yet another song recorded by Sinatra for "Where Are You?" in 1957 at Capitol with arrangements by Gordon Jenkins, in the same session as "The Night We Called It a Day." "Autumn Leaves," a jazz standard, was originally written in 1945 in France by Hungarian composer Joseph Kosma and poet Jacques Prevert as "Les Feuilles Mortes" ("Dead Leaves"). Sublime lyricist Johnny Mercer wrote English words for it in 1947. There are many, many versions of this song, so we'll just note a few: Jo Stafford's big pop hit, an unusual version in Japanese by Nat King Cole, bilingual versions in French and English by Edith Piaf (1950), and Iggy Pop's 2009 cover for his strange Francophile project "Préliminaires." Jerry Lee Lewis, strangely enough given his manic persona, has had a moving version of "Autumn Leaves" as part of his extensive repertoire for decades (there's a YouTube video of Lewis performing the song in 1971).

"Why Try to Change Me Now" (Coleman, McCarthy): Sinatra recorded this twice. The first version, from 1952 (arranged by Percy Faith), was his last recording for Columbia Records and many interpreted the lyrics as a kiss-off to the company. The second recording is from 1959's "No One Cares," another Jenkins-arranged album of "suicide songs" and a thematic sequel of sorts to Dylan favorite "Where Are You?" The song was cowritten by Broadway legend Cy Coleman, of "Sweet Charity" fame. An outstanding modern version was recorded by Fiona Apple for "The Best Is Yet to Come" a 2009 multi-artist tribute to Coleman. Check out the live version at L.A.'s Largo.

"Some Enchanted Evening" (Rodgers and Hammerstein): One of the showstoppers from 1949's hit musical "South Pacific," of course, Sinatra recorded it three times, first when the song was fresh, for a 1949 Columbia single arranged by Axel Stordahl, which didn't sell as well as contemporary versions by Perry Como and Bing Crosby. Sinatra rerecorded it in 1963 with Nelson Riddle as part of the "Reprised Musical Repertory Theater" series of albums based on Broadway musicals that he recorded with showbiz friends. He revived it in the autumn of his years for the H.B. Barnum-led 1967 sessions for "The World We Knew." Other versions? Take your pick, as it's been done by everyone from Art Garfunkel to Harry Connick Jr. to any number of sentimental karaoke drunks around the world.

"Full Moon and Empty Arms" (Rachmaninoff, Kaye and Mossman): Yes, Rachmaninoff as in the famous Russian composer, from whose Piano Concerto No. 2 Kaye and Mossman adapted the melody in 1945. Sinatra had a minor hit on Columbia with it, and it was later done by Eddie Fisher and Sarah Vaughan. It was the track chosen by Dylan to give a sneak peek into the project back in May 2014.

"Where Are You?" (Adamson, McHugh): The title song from 1957 heartbreak concept album "Where Are You?" (and by this point, it should be clear, one of the inspirations of Dylan's "Shadows in the Night"). By the time Sinatra got around to recording it the song was 20 years old, originating in the 1937 film "Top of the Town." The early hit version was by Mildred Bailey in the 1930s, but Sinatra made it his. There are many other good versions, including those by Shirley Bassey, Dinah Washington and this writer's favorite songstress, Julie London. Aretha Franklin recorded a moving rendition in 1963 during her unfairly maligned stint at Columbia Records as a jazz and pop singer.

"What'll I Do" (Berlin): The oldest song on the set, written by Irving Berlin in the early 1920s for a Broadway revue. Jazzman Paul Whiteman had a hit with it in 1924. Sinatra recorded it twice: in 1947 for Columbia with Axel Stordahl and in 1962 for Reprise with Gordon Jenkins. The 1962 version was released on "All Alone," Sinatra's update for his own label, Reprise, of his famous "suicide songs" concept albums for Capitol in the 1950s. The song remained a popular standard for decades and there are good versions by Chet Baker (Dylan and Baker seem to share an affinity for the same torch songs), Lena Horne, Julie London, Sarah Vaughan, Cher and Harry Nilsson. "What'll I Do" was also used by Nelson Riddle as the theme for his score for the 1974 version of "The Great Gatsby" (the one with Robert Redford and Mia Farrow).

"That Lucky Old Sun" (Smith, Gillespie): "Shadows in the Night" closes with the most soulful of the songs Dylan selected. Composed in 1949 as a kind of late-era spiritual/work song, it was recorded by Louis Armstrong, but Frankie Laine had the hit. Sinatra did his version when the song was new, but Laine's became the definitive rendition of 1949 (and a palpable influence on singers who were coming of age at the time like Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash). Jerry Lee Lewis revved it up as a Sun recording, and it was later adopted as a proto-soul standard by Sam Cooke, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin (also during the Columbia years). More recently, Willie Nelson recorded a crystalline version for 1976's "The Sound in Your Mind" (included now as a bonus track to Willie's "Stardust," which Dylan told AARP was a direct influence on "Shadows in the Night") and in 2007 became the centerpiece of a song cycle about California by none other than Brian Wilson.

Sunday, 25 January 2015

Poem and whisky for Burn's Night: Tam O'Shanter

Tam O' Shanter

When chapman billies leave the street,

And drouthy neibors neibors meet;

As market days are wearing late,

And folk begin to tak the gate,

While we sit bousing at the nappy,

An' getting fou and unco happy,

We think na on the lang Scots miles,

The mosses, waters, slaps and stiles,

That lie between us and our hame,

Where sits our sulky, sullen dame,

Gathering her brows like gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

This truth fand honest Tam o' Shanter,

As he frae Ayr ae night did canter:

(Auld Ayr, wham ne'er a town surpasses,

For honest men and bonie lasses).

O Tam! had'st thou but been sae wise,

As taen thy ain wife Kate's advice!

She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum,

A blethering, blustering, drunken blellum;

That frae November till October,

Ae market-day thou was na sober;

That ilka melder wi' the Miller,

Thou sat as lang as thou had siller;

That ev'ry naig was ca'd a shoe on

The Smith and thee gat roarin fou on;

That at the Lord's house, ev'n on Sunday,

Thou drank wi' Kirkton Jean till Monday;

She prophesied that late or soon,

Thou wad be found, deep drown'd in Doon,

Or catch'd wi' warlocks in the mirk,

By Alloway's auld, haunted kirk.

Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet,

To think how mony counsels sweet,

How mony lengthen'd, sage advices,

The husband frae the wife despises!

But to our tale: - Ae market night,

Tam had got planted unco right,

Fast by the ingle, bleezing finely,

Wi' reaming swats that drank divinely;

And at his elbow, Souter Johnie,

His ancient, trusty, drouthy crony:

Tam lo'ed him like a very brither;

They had been fou for weeks thegither.

The night drave on wi' sangs an' clatter;

And aye the ale was growing better:

The Landlady and Tam grew gracious,

Wi' favours secret, sweet and precious:

The Souter tauld his queerest stories;

The Landlord's laugh was ready chorus:

The storm without might rair and rustle,

Tam did na mind the storm a whistle.

Care, mad to see a man sae happy,

E'en drown'd himsel amang the nappy.

As bees flee hame wi' lades o' treasure,

The minutes wing'd their way wi' pleasure:

Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious,

O'er a' the ills o' life victorious!

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow'r, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white - then melts for ever;

Or like the Borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the Rainbow's lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm. -

Nae man can tecther Time nor Tide,

The hour approaches Tam maun ride;

That hour, o' night's black arch the key-stane,

That dreary hour he mounts his beast in;

And sic a night he taks the road in,

As ne'er poor sinner was abroad in.

The wind blew as 'twad blawn its last;

The rattling showers rose on the blast;

The speedy gleams the darkness swallow'd;

Loud, deep, and lang the thunder bellow'd:

That night, a child might understand,

The deil had business on his hand.

Weel-mounted on his grey mare Meg,

A better never leg,

Tam skelpit on thro' dub and mire,

Despising wind, and rain, and fire;

Whiles holding fast his gude blue bonnett,

Whiles crooning o'er some auld Scots sonnet,

Whiles glow'rin round wi' prudent cares,

Lest bogles catch him unawares;

Kirk-Alloway was drawing nigh,

Where ghaists and houlets nightly cry.

By this time he was cross the ford,

Where in the snaw the chapman smoor'd;

And past the birks and meikle stane,

Where drunken Charlie brak's neck-bane;

And thro' the whins, and by the cairn,

Where hunters fand the murder'd bairn;

And near the thorn, aboon the well,

Where Mungo's mither hang'd hersel'.

Before him Doon pours all his floods,

The doubling storm roars thro' the woods,

The lightnings flash from pole to pole,

Near and more near the thunders roll,

When, glimmering thro' the groaning trees,

Kirk-Alloway seem'd in a bleeze,

Thro' ilka bore the beams were glancing,

And loud resounded mirth and dancing.

Inspiring bold John Barleycorn!

What dangers thou canst make us scorn!

Wi' tippeny, we fear nae evil;

Wi' usquabae, we'll face the devil!

The swats sae ream'd in Tammie's noddle,

Fair play, he car'd na deils a boddle,

But Maggie stood, right sair astonish'd,

Till, by the heel and hand admonish'd,

She ventur'd forward on the light;

And wow! Tam saw an unco sight!

Warlocks and witches in a dance:

Nae cotillon, brent new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

A winnock-bunker in the east,

There sat auld Nick, in shape o' beast;

A tousie tyke, black, grim, and large,

To gie them music was his charge.

He screw'd the pipes and gart them skirl,

Till roof and rafters a' did dirl. -

Coffins stood round, like open presses,

That shaw'd the Dead in their last dresses;

And (by some devilish cantraip sleight)

Each in its cauld hand held a light.

By which heroic Tam was able

To note upon the haly table,

A murderer's banes, in gibbet-airns;

Twa span-lang, wee, unchristened bairns;

A thief, new-cutted frae a rape,

Wi' his last gasp his gab did gape;

Five tomahawks, wi' blude red-rusted:

Five scimitars, wi' murder crusted;

A garter which a babe had strangled:

A knife, a father's throat had mangled,

Whom his ain son of life bereft,

The grey hairs yet stack to the heft;

Wi' mair of horrible and awfu',

Which even to name was be unlawfu'.

As Tammie glowr'd, amaz'd, and curious,

The mirth and fun grew fast and furious;

The Piper loud and louder blew,

The dancers quick and quicker flew,

They reel'd, they set, they cross'd, they cleekit,

Till ilka carlin swat and reekit,

And coost her duddies to the wark,

And linkit at it in her sark!

Now Tam, O Tam! had they been queans,

A' plump and strapping in their teens!

Their sarks, instead o' creeshie flainen,

Been snaw-white seventeen-hunder linen! -

Thir breeks o' mine, my only pair,

That aince were plush, o' guid blue hair,

I wud hae gien them off my hurdies,

For ae blink o' the bonie burdies!

But wither'd beldams, auld and droll,

Rigwoodie hags wad spean a foal,

Louping an' flinging on a crummock,

I wonder did na turn thy stomach.

But Tam kent what was what fu' brawlie:

There was ae winsome wench and waulie

That night enlisted in the core,

Lang after ken'd on Carrick shore

(For mony a beast to dead she shot,

And perish'd mony a bonie boat,

And shook baith meikle corn and bear,

And kept the country-side in fear);

Her cutty sark, o' Paisley harn,

That while a lassie she had worn,

In longitude tho' sorely scanty,

It was her best, and she was vauntie.

Ah! little ken'd thy reverend grannie,

That sark she coft for her wee Nannie,

Wi' twa pund Scots ('twas a' her riches),

Wad ever grac'd a dance of witches!

But here my Muse her wing maun cour,

Sic flights are far beyond her power;

To sing how Nannie lap and flang

(A souple jade she was and strang),

And how Tam stood, like ane bewitch'd,

And thought his very een enrich'd:

Even Satan glowr'd, and fidg'd fu' fain,

And hotch'd and blew wi' might and main:

Till first ae caper, syne anither,

Tam tint his reason a' thegither,

And roars out, "Weel done, Cutty-sark!"

And in an instant all was dark:

And scarcely had he Maggie rallied,

When out the hellish legion sallied.

As bees bizz out wi' angry fyke,

When plundering herds assail their byke;

As open pussie's mortal foes,

When, pop! she starts before their nose;

As eager runs the market-crowd,

When "Catch the thief!" resounds aloud;

So Maggie runs, the witches follow,

Wi' mony an eldritch skreich and hollo.

Ah, Tam! Ah, Tam! thou'll get thy fairin!

In hell they'll roast thee like a herrin!

In vain thy Kate awaits thy comin!

Kate soon will be a woefu' woman!

Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg,

And win the key-stane o' the brig;

There, at them thou thy tail may toss,

A running stream they dare ne cross.

But ere the key-stane she could make,

The fient a tail she had to shake!

For Nannie, far before the rest,

Hard upon noble Maggie prest,

And flew at Tam wi' furious ettle;

But little wist she Maggie's mettle!

Ae spring brought off her master hale,

But left behind her ain grey tale:

The carlin claught her by the rump,

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

Now, wha this tale o' truth shall read,

Ilk man, and mother's son, take heed:

Whene'er to Drink you are inclin'd,

Or Cutty-sarks rin in your mind,

Think ye may buy the joys o'er dear;

Remember Tam o' Shanter's mare.

And drouthy neibors neibors meet;

As market days are wearing late,

And folk begin to tak the gate,

While we sit bousing at the nappy,

An' getting fou and unco happy,

We think na on the lang Scots miles,

The mosses, waters, slaps and stiles,

That lie between us and our hame,

Where sits our sulky, sullen dame,

Gathering her brows like gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

This truth fand honest Tam o' Shanter,

As he frae Ayr ae night did canter:

(Auld Ayr, wham ne'er a town surpasses,

For honest men and bonie lasses).

O Tam! had'st thou but been sae wise,

As taen thy ain wife Kate's advice!

She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum,

A blethering, blustering, drunken blellum;

That frae November till October,

Ae market-day thou was na sober;

That ilka melder wi' the Miller,

Thou sat as lang as thou had siller;

That ev'ry naig was ca'd a shoe on

The Smith and thee gat roarin fou on;

That at the Lord's house, ev'n on Sunday,

Thou drank wi' Kirkton Jean till Monday;

She prophesied that late or soon,

Thou wad be found, deep drown'd in Doon,

Or catch'd wi' warlocks in the mirk,

By Alloway's auld, haunted kirk.

Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet,

To think how mony counsels sweet,

How mony lengthen'd, sage advices,

The husband frae the wife despises!

But to our tale: - Ae market night,

Tam had got planted unco right,

Fast by the ingle, bleezing finely,

Wi' reaming swats that drank divinely;

And at his elbow, Souter Johnie,

His ancient, trusty, drouthy crony:

Tam lo'ed him like a very brither;

They had been fou for weeks thegither.

The night drave on wi' sangs an' clatter;

And aye the ale was growing better:

The Landlady and Tam grew gracious,

Wi' favours secret, sweet and precious:

The Souter tauld his queerest stories;

The Landlord's laugh was ready chorus:

The storm without might rair and rustle,

Tam did na mind the storm a whistle.

Care, mad to see a man sae happy,

E'en drown'd himsel amang the nappy.

As bees flee hame wi' lades o' treasure,

The minutes wing'd their way wi' pleasure:

Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious,

O'er a' the ills o' life victorious!

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow'r, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white - then melts for ever;

Or like the Borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the Rainbow's lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm. -

Nae man can tecther Time nor Tide,

The hour approaches Tam maun ride;

That hour, o' night's black arch the key-stane,

That dreary hour he mounts his beast in;

And sic a night he taks the road in,

As ne'er poor sinner was abroad in.

The wind blew as 'twad blawn its last;

The rattling showers rose on the blast;

The speedy gleams the darkness swallow'd;

Loud, deep, and lang the thunder bellow'd:

That night, a child might understand,

The deil had business on his hand.

Weel-mounted on his grey mare Meg,

A better never leg,

Tam skelpit on thro' dub and mire,

Despising wind, and rain, and fire;

Whiles holding fast his gude blue bonnett,

Whiles crooning o'er some auld Scots sonnet,

Whiles glow'rin round wi' prudent cares,

Lest bogles catch him unawares;

Kirk-Alloway was drawing nigh,

Where ghaists and houlets nightly cry.

By this time he was cross the ford,

Where in the snaw the chapman smoor'd;

And past the birks and meikle stane,

Where drunken Charlie brak's neck-bane;

And thro' the whins, and by the cairn,

Where hunters fand the murder'd bairn;

And near the thorn, aboon the well,

Where Mungo's mither hang'd hersel'.

Before him Doon pours all his floods,

The doubling storm roars thro' the woods,

The lightnings flash from pole to pole,

Near and more near the thunders roll,

When, glimmering thro' the groaning trees,

Kirk-Alloway seem'd in a bleeze,

Thro' ilka bore the beams were glancing,

And loud resounded mirth and dancing.

Inspiring bold John Barleycorn!

What dangers thou canst make us scorn!

Wi' tippeny, we fear nae evil;

Wi' usquabae, we'll face the devil!

The swats sae ream'd in Tammie's noddle,

Fair play, he car'd na deils a boddle,

But Maggie stood, right sair astonish'd,

Till, by the heel and hand admonish'd,

She ventur'd forward on the light;

And wow! Tam saw an unco sight!

Warlocks and witches in a dance:

Nae cotillon, brent new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

A winnock-bunker in the east,

There sat auld Nick, in shape o' beast;

A tousie tyke, black, grim, and large,

To gie them music was his charge.

He screw'd the pipes and gart them skirl,

Till roof and rafters a' did dirl. -

Coffins stood round, like open presses,

That shaw'd the Dead in their last dresses;

And (by some devilish cantraip sleight)

Each in its cauld hand held a light.

By which heroic Tam was able

To note upon the haly table,

A murderer's banes, in gibbet-airns;

Twa span-lang, wee, unchristened bairns;

A thief, new-cutted frae a rape,

Wi' his last gasp his gab did gape;

Five tomahawks, wi' blude red-rusted:

Five scimitars, wi' murder crusted;

A garter which a babe had strangled:

A knife, a father's throat had mangled,

Whom his ain son of life bereft,

The grey hairs yet stack to the heft;

Wi' mair of horrible and awfu',

Which even to name was be unlawfu'.

As Tammie glowr'd, amaz'd, and curious,

The mirth and fun grew fast and furious;

The Piper loud and louder blew,

The dancers quick and quicker flew,

They reel'd, they set, they cross'd, they cleekit,

Till ilka carlin swat and reekit,

And coost her duddies to the wark,

And linkit at it in her sark!

Now Tam, O Tam! had they been queans,

A' plump and strapping in their teens!

Their sarks, instead o' creeshie flainen,

Been snaw-white seventeen-hunder linen! -

Thir breeks o' mine, my only pair,

That aince were plush, o' guid blue hair,

I wud hae gien them off my hurdies,

For ae blink o' the bonie burdies!

But wither'd beldams, auld and droll,

Rigwoodie hags wad spean a foal,

Louping an' flinging on a crummock,

I wonder did na turn thy stomach.

But Tam kent what was what fu' brawlie:

There was ae winsome wench and waulie

That night enlisted in the core,

Lang after ken'd on Carrick shore

(For mony a beast to dead she shot,

And perish'd mony a bonie boat,

And shook baith meikle corn and bear,

And kept the country-side in fear);

Her cutty sark, o' Paisley harn,

That while a lassie she had worn,

In longitude tho' sorely scanty,

It was her best, and she was vauntie.

Ah! little ken'd thy reverend grannie,

That sark she coft for her wee Nannie,

Wi' twa pund Scots ('twas a' her riches),

Wad ever grac'd a dance of witches!

But here my Muse her wing maun cour,

Sic flights are far beyond her power;

To sing how Nannie lap and flang

(A souple jade she was and strang),

And how Tam stood, like ane bewitch'd,

And thought his very een enrich'd:

Even Satan glowr'd, and fidg'd fu' fain,

And hotch'd and blew wi' might and main:

Till first ae caper, syne anither,

Tam tint his reason a' thegither,

And roars out, "Weel done, Cutty-sark!"

And in an instant all was dark:

And scarcely had he Maggie rallied,

When out the hellish legion sallied.

As bees bizz out wi' angry fyke,

When plundering herds assail their byke;

As open pussie's mortal foes,

When, pop! she starts before their nose;

As eager runs the market-crowd,

When "Catch the thief!" resounds aloud;

So Maggie runs, the witches follow,

Wi' mony an eldritch skreich and hollo.

Ah, Tam! Ah, Tam! thou'll get thy fairin!

In hell they'll roast thee like a herrin!

In vain thy Kate awaits thy comin!

Kate soon will be a woefu' woman!

Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg,

And win the key-stane o' the brig;

There, at them thou thy tail may toss,

A running stream they dare ne cross.

But ere the key-stane she could make,

The fient a tail she had to shake!

For Nannie, far before the rest,

Hard upon noble Maggie prest,

And flew at Tam wi' furious ettle;

But little wist she Maggie's mettle!

Ae spring brought off her master hale,

But left behind her ain grey tale:

The carlin claught her by the rump,

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

Now, wha this tale o' truth shall read,

Ilk man, and mother's son, take heed:

Whene'er to Drink you are inclin'd,

Or Cutty-sarks rin in your mind,

Think ye may buy the joys o'er dear;

Remember Tam o' Shanter's mare.

ROBERT BURNS

Burns Night 2015: 11 best whiskies

Our pick of the whiskies to toast the life and work of Scotland's national poet on January 25

Will Dean and Samuel Muston

Thursday 22 January 2015

Mark Burns Night in suitable style: with a dram of one of these whiskies, all hailing from the British Isles - with one exception for renegade celebrators.

1. Lagavulin 16-year-old single malt

The pride of Islay, Lagavulin’s standard single malt is a consistent winner of high scores in the whisky ratings world, winning double gold medals for four consecutive years in the mid aughts in the San Francisco World Spirits awards. It’s also the sip of choice of one of the best whisky drinkers on television, Parks and Recreation’s Ron Swanson. No better endorsement than that.

2. Glenlivet 12-year-old

2. Glenlivet 12-year-old

A fine go-to single malt for the casual supper - always worth having in the cabinet. It’s not for no good reason that the famous Scottish distillery’s 12-year-old remains one of the world’s top sellers. A smooth, golden, oaky Scottish drop that’s great post-dinner or as a toast for Rabbie himself.

3. Bushmills 16-year-old

3. Bushmills 16-year-old

Tricky to get hold of - and with good reason - the giant of Irish whisky making’s 16-year-old treasure is matured in a combination of barrels. This three-wood approach sees one whisky matured in a bourbon barrel, another in a Spanish Oloroso sherry butt before the two are combined in a port cask. The result of this concoction. A sweet, nutty taste of malt heaven.

4. Talisker Port Ruighe

4. Talisker Port Ruighe

Like the Bushmills 16, this peaty, smoky whisky from Talisker is matured in separate oak casks - one normal oak, the other charred - before being finished in port casks, giving it that lovely, slightly amber glow. Perfect for a cold night by the fire.

5. Caol Ila 12-year single malt

5. Caol Ila 12-year single malt

Also on Islay is the Caol Ila distillery (its name means “Sound of Islay”). The 12-year single malt is one of the island’s lighter whiskies and rather smooth on the the tastebuds, though it retains a signature smokiness.

6. Balblair 2003

6. Balblair 2003

So good is Balblair’s offering that we have included two of their whiskies. Bottled in 2013, this 10-year-old malt number is long on honey and citrus flavours co-mingled with a touch of the floral. It is an absolute cracker. Worth a tipple for its long, sweet finish alone.

7. Bowmore Black Rock

7. Bowmore Black Rock

Burnt orange, peat smoke and treacle - this sherry-cask matured single malt has all things you want on a cold winter evening. It’s real draw, though, is the fact that it deftly balance smokiness with richness, and even has a touch of sea salt-flavour to it. A reliable every-day drinker.

8. Old Pulteney 17-Year-Old

8. Old Pulteney 17-Year-Old

This teenager scooped a gold medal for top-notch quality at the 2014 International Wine and Spirit Competition. The fact that it was matured in Pedro Ximenez and Oloroso sherry casks shines through in the tasting: it has a complex sweetness to it that runs from peach to raisin.

9. Glen Grant 10 Year Old

9. Glen Grant 10 Year Old

This is best described as a ‘subtle’ single malt. It won’t dance a can-can on your tongue, by any means, but there is a reason it is a stalwart of Jim Murray’s whisky bible and won gold at the San Francisco World Spirit competition. It’s easy-going with a touch of peat to it, along with lots of vanilla sweetness.

10. Balblair 1990

10. Balblair 1990

Balblair has been slaking the nations thirst for Scotch since 1790 – and you can see all their sure-footed brilliance in this 25-year-old. It is matured in both American oak bourbon and Spanish sherry casks, giving it a warm amber hue and a rich chocolate and raisin palate and cocoa-ish finish.

11. Suntory Whisky The Hakushi Single Malt

11. Suntory Whisky The Hakushi Single Malt

Ok, so this isn’t from Scotland – the distillery is in the foothills of Mount Kaikomagatake, Japan -- but it most definitely wouldn’t have the Bard of Ayrshire rolling in his grave. Both heavy and lightly peated malts have been used in this to give a complex character with not a little of the herbaceous about it. Very good in a Highball.

Verdict

For your Burns Night toast, our pick of the nips is Balblair'sspectacular 2003 offering. If you're after a spirit-cupboard staple, keep a bottle of Glenlivet 12-year-old on the shelf.

Friday, 23 January 2015

Wednesday, 21 January 2015

Stan Laurel: Comic Genius in Tynemouth

Stan Laurel: Comic Genius on North Tyneside

Aileen Brewis

19 January 2015

The comic genius of Stan Laurel will be celebrated in North Tyneside next month exactly 50 years after his death on 23rd February 1965.

The Grand Hotel in Tynemouth will host an evening of celebration on Monday 23 February with a talk, excerpts from a play and screenings of two classic films.

Delivered in partnership between North Tyneside Council, Whitley Bay Film Festival and theatre company Cloud Nine Productions, the evening will be a great celebration of both Laurel and Hardy and the life of Stan Laurel.

It will include:

A talk by Danny Lawrence, author of The Making of Stan Laurel: Echoes of a British Boyhood. Danny will talk about the significance of the time Stan Laurel spent in North Tyneside and how echoes of this experience can be discerned in some of his most famous works.

Cloud Nine Productions will perform an excerpt of Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth a play by the eminent local playwright Tom Hadaway.

The evening will continue with the screening of two Laurel and Hardy classic films, The Music Box and Towed in a Hole, presented on the big screen by the Whitley Bay Film Festival team.

Tickets cost £15 and are on sale from Friday 23rd January. Demand is expected to be very high so early booking is advisable. Tickets are available from North Tyneside Council at North Shields, Whitley Bay, Wallsend and White Swan Customer First Centres. They are also available through Cloud Nine Productions Tel. (0191) 253 1901 and Whitley Bay Film Festival Tel. (0191) 2802413 (www.whitleybayfilmfestival.co.uk ).

Stan Laurel (Arthur Stanley Jefferson) spent his formative years in North Tyneside. Stan grew up in North Shields after his family located to the area where his father would manage a local theatre. He moved to North Shields at the age of five in 1895 and remained there until the age of 15. Stan's connection with the town continued throughout his life. He was actively corresponding with people from the town until his death in 1965.

Danny Lawrence, The Making of Stan Laurel: Echoes of a British Boyhood (Published McFarland 2011)

Author Danny Lawrence is a retired sociologist from the University of Nottingham. He was born and raised a few hundred yards from Stan's North Shields home. His groundbreaking biography examines Laurel's family background, his formative years and his struggle to establish a show business career. The book analyses how Stan's boyhood experiences are often echoed in some of the best known Laurel and Hardy films.

Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth - Tom Hadaway

An unfinished play by North East playwright Tom Hadaway. The script is currently being completed by Tom's playwright daughter Pauline Hadaway in preparation for a full production later in the year.

Cloud Nine Productions will perform a sample of this outstanding piece of work.

The Grand Hotel

The Grand Hotel provides a fitting venue for this Stan Laurel anniversary event. Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy are among many esteemed guests who have stayed at the Grand. The comedy duo first stayed at the Grand on Thursday 28th July 1932. They returned again on Wednesday 26th February 1947, for a civic reception with the Mayor of Tynemouth, while appearing at the Newcastle Empire Theatre. Their last stay at the Grand was from Monday 17th March 1952, for two weeks, while they were once again performing at the Newcastle Empire.

The hotel has a room named after the duo in recognition of their association with this historic Tynemouth landmark.

http://www.northtyneside.gov.uk/browse-display.shtml?p_ID=558201&p_subjectCategory=23

North East set to mark anniversary of death of Stan Laurel with Tynemouth event

Grand Hotel in Tynemouth to host tribute event to mark 50th anniversary of comic Stan Laurel's death on February 23

The comic genius of Stan Laurel will be celebrated in North Tyneside next month exactly 50 years after his death on 23rd February 1965.

The Grand Hotel in Tynemouth will host an evening of celebration on Monday 23 February with a talk, excerpts from a play and screenings of two classic films.

Delivered in partnership between North Tyneside Council, Whitley Bay Film Festival and theatre company Cloud Nine Productions, the evening will be a great celebration of both Laurel and Hardy and the life of Stan Laurel.

It will include:

A talk by Danny Lawrence, author of The Making of Stan Laurel: Echoes of a British Boyhood. Danny will talk about the significance of the time Stan Laurel spent in North Tyneside and how echoes of this experience can be discerned in some of his most famous works.

Cloud Nine Productions will perform an excerpt of Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth a play by the eminent local playwright Tom Hadaway.

The evening will continue with the screening of two Laurel and Hardy classic films, The Music Box and Towed in a Hole, presented on the big screen by the Whitley Bay Film Festival team.

Tickets cost £15 and are on sale from Friday 23rd January. Demand is expected to be very high so early booking is advisable. Tickets are available from North Tyneside Council at North Shields, Whitley Bay, Wallsend and White Swan Customer First Centres. They are also available through Cloud Nine Productions Tel. (0191) 253 1901 and Whitley Bay Film Festival Tel. (0191) 2802413 (www.whitleybayfilmfestival.co.uk ).

Stan Laurel (Arthur Stanley Jefferson) spent his formative years in North Tyneside. Stan grew up in North Shields after his family located to the area where his father would manage a local theatre. He moved to North Shields at the age of five in 1895 and remained there until the age of 15. Stan's connection with the town continued throughout his life. He was actively corresponding with people from the town until his death in 1965.

Danny Lawrence, The Making of Stan Laurel: Echoes of a British Boyhood (Published McFarland 2011)

Author Danny Lawrence is a retired sociologist from the University of Nottingham. He was born and raised a few hundred yards from Stan's North Shields home. His groundbreaking biography examines Laurel's family background, his formative years and his struggle to establish a show business career. The book analyses how Stan's boyhood experiences are often echoed in some of the best known Laurel and Hardy films.

Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth - Tom Hadaway

An unfinished play by North East playwright Tom Hadaway. The script is currently being completed by Tom's playwright daughter Pauline Hadaway in preparation for a full production later in the year.

Cloud Nine Productions will perform a sample of this outstanding piece of work.

The Grand Hotel

The Grand Hotel provides a fitting venue for this Stan Laurel anniversary event. Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy are among many esteemed guests who have stayed at the Grand. The comedy duo first stayed at the Grand on Thursday 28th July 1932. They returned again on Wednesday 26th February 1947, for a civic reception with the Mayor of Tynemouth, while appearing at the Newcastle Empire Theatre. Their last stay at the Grand was from Monday 17th March 1952, for two weeks, while they were once again performing at the Newcastle Empire.

The hotel has a room named after the duo in recognition of their association with this historic Tynemouth landmark.

http://www.northtyneside.gov.uk/browse-display.shtml?p_ID=558201&p_subjectCategory=23

North East set to mark anniversary of death of Stan Laurel with Tynemouth event

Grand Hotel in Tynemouth to host tribute event to mark 50th anniversary of comic Stan Laurel's death on February 23

Tom Henderson

20 January 2015

The 50th anniversary of the death of comedian Stan Laurel will be marked by a tribute event on Tyneside.

Stan spent his formative years in North Tyneside, and the Grand Hotel in Tynemouth will host the event on February 23 with a talk, excerpts from a play and screenings of two classic films.

The evening will be staged by North Tyneside Council, Whitley Bay Film Festival and Cullercoats theatre company Cloud Nine.

It will include a talk by Danny Lawrence, author of The Making of Stan Laurel: Echoes of a British Boyhood.

He will talk about the significance of the time Stan Laurel spent in North Tyneside and how evidence of this experience can be discerned in some of his most famous works.

Cloud Nine will perform an excerpt of Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth, a play by the North Shields playwright Tom Hadaway.

The evening will continue with the screening of two Laurel and Hardy classic films, The Music Box and Towed in a Hole, presented by the Whitley Bay Film Festival team.

Tickets cost £15 and are on sale from January 23.

Tickets are available from North Tyneside Council at North Shields, Whitley Bay, Wallsend and White Swan Customer First Centres.

They are also available through Cloud Nine Productions and Whitley Bay Film Festival.

Stan Laurel (Arthur Stanley Jefferson) grew up in Dockwray Square in North Shields after his family moved to the area where his father would managed local theatres. He moved to North Shields at the age of five in 1895 and remained there until the age of 15. Stan’s connection with the town continued throughout his life. He was actively corresponding with people from the town until his death in 1965.

Author Danny Lawrence is a retired university sociologist who was born and raised a few hundred yards from Stan’s North Shields home.

His biography examines Laurel’s family background, his formative years and his struggle to establish a show business career.

Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth is an unfinished play by the late Tom Hadaway.

It is currently being completed by Tom’s playwright daughter Pauline Hadaway in preparation for a full production later in the year.

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy first stayed at the Grand Hotel in July 1932.

They returned on February 26 1947, for a civic reception with the Mayor of Tynemouth, while appearing at the Newcastle Empire Theatre.

Their last stay at the Grand was from March 17 1952, for two weeks, while they were once again performing at the Newcastle Empire.

The hotel has a room named after the duo.

The 50th anniversary of the death of comedian Stan Laurel will be marked by a tribute event on Tyneside.

Stan spent his formative years in North Tyneside, and the Grand Hotel in Tynemouth will host the event on February 23 with a talk, excerpts from a play and screenings of two classic films.

The evening will be staged by North Tyneside Council, Whitley Bay Film Festival and Cullercoats theatre company Cloud Nine.

It will include a talk by Danny Lawrence, author of The Making of Stan Laurel: Echoes of a British Boyhood.

He will talk about the significance of the time Stan Laurel spent in North Tyneside and how evidence of this experience can be discerned in some of his most famous works.

Cloud Nine will perform an excerpt of Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth, a play by the North Shields playwright Tom Hadaway.

The evening will continue with the screening of two Laurel and Hardy classic films, The Music Box and Towed in a Hole, presented by the Whitley Bay Film Festival team.

Tickets cost £15 and are on sale from January 23.

Tickets are available from North Tyneside Council at North Shields, Whitley Bay, Wallsend and White Swan Customer First Centres.

They are also available through Cloud Nine Productions and Whitley Bay Film Festival.

Stan Laurel (Arthur Stanley Jefferson) grew up in Dockwray Square in North Shields after his family moved to the area where his father would managed local theatres. He moved to North Shields at the age of five in 1895 and remained there until the age of 15. Stan’s connection with the town continued throughout his life. He was actively corresponding with people from the town until his death in 1965.

Author Danny Lawrence is a retired university sociologist who was born and raised a few hundred yards from Stan’s North Shields home.

His biography examines Laurel’s family background, his formative years and his struggle to establish a show business career.

Laurel and Hardy in Tynemouth is an unfinished play by the late Tom Hadaway.

It is currently being completed by Tom’s playwright daughter Pauline Hadaway in preparation for a full production later in the year.

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy first stayed at the Grand Hotel in July 1932.

They returned on February 26 1947, for a civic reception with the Mayor of Tynemouth, while appearing at the Newcastle Empire Theatre.

Their last stay at the Grand was from March 17 1952, for two weeks, while they were once again performing at the Newcastle Empire.

The hotel has a room named after the duo.

Tuesday, 20 January 2015

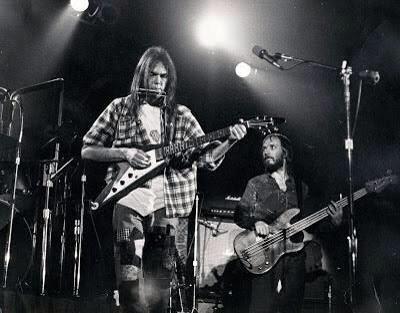

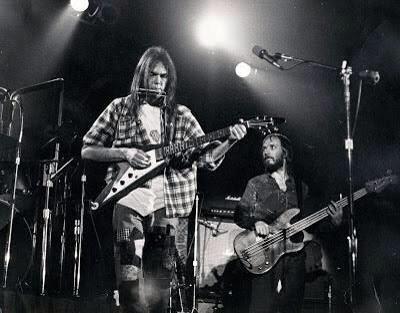

Tim Drummond and Dallas Taylor RIP

Steve Chawkins

Dallas Taylor liked to say that he made his first million — and his last million — by the time he was 21.

The rock drummer was a key sideman for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. He played at Woodstock, appeared on seven top-selling albums and bought three Ferraris. He also stabbed himself in the stomach with a butcher knife and drank so heavily that he required a liver transplant in 1990, five years after becoming sober.

Taylor, who went on to become an addiction counselor specializing in interventions and in reuniting alcoholics and addicts with their families, died Sunday in a Los Angeles hospital. He was 66.

He had been in failing health for some time, his wife, Patti McGovern-Taylor, said.

McGovern-Taylor gave her ailing husband one of her kidneys in 2007.

Taylor's health forced him to largely exit the music business following his liver transplant. But he continued to treat musicians and other celebrities with addiction problems. In a 1994 Times essay, he wrote about Kurt Cobain, the 27-year-old lead singer of the rock band Nirvana who killed himself in his Seattle home after checking out of a drug rehab facility.

"I understand what it is like to be an angry, depressed addict who needs so badly to be liked that he gets on stage and sweats and bleeds and hopes that people will somehow connect," he wrote.

"But as addicts whose only real happiness is being high — whether it's on dope or music, writing, acting or painting — success becomes our worst enemy. When self-hatred runs so deep, it is never alleviated by fame or wealth."

Dallas Woodrow Taylor Jr. was born in Denver on April 7, 1948, and raised in San Antonio. He was the son of a stunt pilot. When he was 4, he told People magazine, his parents' divorce gave him ulcers, which his mother treated with a preparation containing opium.

When he was about 10, he saw the "The Gene Krupa Story," a screen biography of the jazz drummer, and his course in life was set. He dropped out of high school at 16 and headed for Hollywood, where he tasted success with the rock band Clear Light.

"It was the Grateful Dead of the L.A. psychedelic rock scene," said Lee Houskeeper, a San Francisco publicist who was officially named Clear Light's "seer and overseer" — their road manager — by Elektra Records.

In the late 1960s, Taylor met David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Graham Nash, joining them on their first album, "Crosby, Stills and Nash." He also performed with them when they added Neil Young and belatedly showed up at Woodstock.

"It took cajoling," Houskeeper said, "but they finally came."

At a time when excessive drug use was common in the music industry, Taylor's habit stood out. He was fired from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young after their 1970 album, "Déjà Vu." Keith Moon, the notoriously self-destructive drummer for the Who, warned Taylor about the price he ultimately would have to pay.

"Keith was always rock's No. 1 bad boy — he invented the whole thing with trashing hotel rooms," Taylor told The Times in 1990. "But I remember him telling me, 'Dallas, you do too much drugs.'"

Taylor was diagnosed with terminal liver disease in 1989. His friends in music held a benefit concert in 1990 to help fund his transplant.

Taylor also performed with Stephen Stills' band Manassas.

After he became sober, he acquired a credential in treating addictions, first working with troubled adolescents, McGovern-Taylor said.

"He found that he loved it," she said. "He identified with these kids and saw each in himself."

"He saved a lot of lives and his own in the process," she said.

In addition to his wife, Taylor's survivors include son Dallas, daughters Sharlotte and Lisa, and five grandchildren. He had several earlier marriages.

Bassist Tim Drummond Dies at 74

Michael Gallucci

January 12, 2015

Bassist Tim Drummond — who played with Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, among others — has died at the age of 74. No cause of death has been announced.

Rolling Stone reports that Drummond, who played on most on Young’s classic ’70s albums, died on Saturday. The coroner’s office in St. Louis County, Mo., confirmed the news.

Drummond was born on April 20, 1940, in Canton, Ill. During his 40-plus years of making music, he played with a wide range of artists, including country legend Conway Twitty, R&B great James Brown, jazz icon Miles Davis and pop singer-songwriter Jewel.

But he’s best known for his work with classic rockers like Dylan, Young, Eric Clapton and Joe Cocker. In addition to playing on Young’s classic albums like ‘Harvest’ and ‘Comes a Time,’ Drummond was a member of his side bands the International Harvesters, the Shocking Pinks and the Stray Gators. He was also the bass player on Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s notorious 1974 tour.

Over the years, Drummond played on albums by the Beach Boys, Ry Cooder and Don Henley. He also helped write some of the songs he performed, including Dylan’s ‘Saved’ (he played on all three of Dylan’s gospel albums from the late ’70s and early ’80s) and Cooder’s ‘Down in Hollywood.’

http://ultimateclassicrock.com/tim-drummond-dies/

Tim Drummond, Bassist for Neil Young and Bob Dylan, Dead at 74

In-demand session bassist performed with everyone from James Brown and Miles Davis to Jewel and the Beach Boys

Bassist Tim Drummond — who played with Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, among others — has died at the age of 74. No cause of death has been announced.

Rolling Stone reports that Drummond, who played on most on Young’s classic ’70s albums, died on Saturday. The coroner’s office in St. Louis County, Mo., confirmed the news.

Drummond was born on April 20, 1940, in Canton, Ill. During his 40-plus years of making music, he played with a wide range of artists, including country legend Conway Twitty, R&B great James Brown, jazz icon Miles Davis and pop singer-songwriter Jewel.

But he’s best known for his work with classic rockers like Dylan, Young, Eric Clapton and Joe Cocker. In addition to playing on Young’s classic albums like ‘Harvest’ and ‘Comes a Time,’ Drummond was a member of his side bands the International Harvesters, the Shocking Pinks and the Stray Gators. He was also the bass player on Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s notorious 1974 tour.

Over the years, Drummond played on albums by the Beach Boys, Ry Cooder and Don Henley. He also helped write some of the songs he performed, including Dylan’s ‘Saved’ (he played on all three of Dylan’s gospel albums from the late ’70s and early ’80s) and Cooder’s ‘Down in Hollywood.’

Tim Drummond, Bassist for Neil Young and Bob Dylan, Dead at 74

In-demand session bassist performed with everyone from James Brown and Miles Davis to Jewel and the Beach Boys

Daniel Kreps

January 12, 2015

Journeyman bassist Tim Drummond, who performed with Neil Young, Crosby, Stills and Nash and Bob Dylan among many more rock legends, passed away January 10th, the St. Louis County, Missouri coroner's office confirmed to Rolling Stone. No cause of death was given but investigators revealed there was no trauma.

Drummond served as primary bassist on Young's 1972 masterpiece Harvest and contributed to every studio LP the singer-songwriter released from 1974's On the Beach to 1980'sHawks & Doves. Drummond was also a member of Young's short-lived backup bands the Shocking Pinks, the Stray Gators and the International Harvesters. After reuniting with the Harvest crew for 1992's Harvest Moon, Drummond's two-decade-long tenure with Young ended with the rocker's 1993 MTV Unplugged performance.

Astrid Young, Neil Young's half-sister who played alongside Drummond on Harvest Moon, wrote on Facebook, "RIP Tim Drummond. Long may you run."

"One of the best bass players and a great guy. Sad to hear this," producer Craig Leon tweeted.

Drummond's credits run deep and diverse and include the Beach Boys' 15 Big Ones, Don Henley's Building the Perfect Beast, a trio of Ry Cooder albums and Jewel's Pieces of You. The bassist performed alongside legends Miles Davis, John Lee Hooker and Taj Mahal on Jack Nitzsche's score for the 1990 film The Hot Spot and collaborated with the likes of James Brown, Lonnie Mack, Rick Danko, J.J. Cale and John Mayall through the years.

In addition to being an in-demand session bassist, Drummond also co-wrote "Saved" with Bob Dylan, the title track from Dylan's 1980 album. Drummond was on the bass for the entire run of Dylan's "gospel trilogy" – Slow Train Coming, Saved and Shot of Love – and, along with longtime collaborators keyboardist Spooner Oldham and drummer Jim Keltner, was a member of the powerful backup band that accompanied Dylan on his Slow Train Coming tour.