Thursday, 31 January 2019

Tuesday, 29 January 2019

John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing at Two Temple Place, London - review

Portrait of John Ruskin, attributed to Charles Fairfax Murray

Two Temple Place, London

The influential critic, social reformer and troubled genius profoundly changed British culture. In his 200th anniversary year, can this exhibition help us see him clearly?

Jonathan Jones

The Guardian

Thu 24 Jan 2019

Art critic, geologist, botanist, Alpinist, architectural theorist and social reformer – maybe even revolutionary – John Ruskin gazes with troubled intensity from a watercolour portrait that dates from when he was on the verge of losing his mind. Half his face is in shadow, the other in mountain sunlight. His blue-green eyes stare almost too intently. There’s something wrong behind them. The following year, over Christmas 1876 in his beloved Venice, Ruskin would start to hallucinate. Breakdowns would follow and he eventually withdrew from the world, cared for at home on a healthy inheritance from his wine merchant father, until his death in 1900.

Ruskin’s manic portrait, attributed to Charles Fairfax Murray but quite possibly the critic’s own work, fits well into the late-Victorian interior of Two Temple Place, laden with rich wooden carvings, panelling and stained glass. Or does it? It’s safe to say its architect was influenced by Ruskin’s gothic vision of architecture. Yet it’s an equally safe guess that Ruskin would have loathed it, for this neo-Tudor fantasy was created for the American millionaire William Waldorf Astor. In his book The Stones of Venice, the bible of the gothic revival, Ruskin denounces the very opulence and selfishness this building represents. Medieval gothic, for him, is an art of communal togetherness, created by a morally superior age that respected honest work and condemned capitalist usury.

Thu 24 Jan 2019

Art critic, geologist, botanist, Alpinist, architectural theorist and social reformer – maybe even revolutionary – John Ruskin gazes with troubled intensity from a watercolour portrait that dates from when he was on the verge of losing his mind. Half his face is in shadow, the other in mountain sunlight. His blue-green eyes stare almost too intently. There’s something wrong behind them. The following year, over Christmas 1876 in his beloved Venice, Ruskin would start to hallucinate. Breakdowns would follow and he eventually withdrew from the world, cared for at home on a healthy inheritance from his wine merchant father, until his death in 1900.

Ruskin’s manic portrait, attributed to Charles Fairfax Murray but quite possibly the critic’s own work, fits well into the late-Victorian interior of Two Temple Place, laden with rich wooden carvings, panelling and stained glass. Or does it? It’s safe to say its architect was influenced by Ruskin’s gothic vision of architecture. Yet it’s an equally safe guess that Ruskin would have loathed it, for this neo-Tudor fantasy was created for the American millionaire William Waldorf Astor. In his book The Stones of Venice, the bible of the gothic revival, Ruskin denounces the very opulence and selfishness this building represents. Medieval gothic, for him, is an art of communal togetherness, created by a morally superior age that respected honest work and condemned capitalist usury.

Study of Spray of Dead Oak Leaves, 1879, by John Ruskin Photograph: Hazel Drummond/Collection of the Guild of St George/Museums Sheffield

And there, in a nutshell, is the reason for today’s Ruskin revival. In the late 20th century, Ruskin was considered a bit of a joke. Even now, his name for many people evokes a sexually repressed Victorian oddball. Even the curators of this loving homage can’t resist telling us how working-class audiences laughed at his “megaphone” lecturing voice and quirky bird imitations. Yet as the deepest crisis of capitalism since the 1930s drags on and Victorian critics of the cash nexus, from Karl Marx to William Morris, are taken seriously once more, Ruskin’s social radicalism looks urgent again. He was ahead of them all. In 1860, he horrified readers of the Cornhill magazine with a series of articles that denounced free-market economics. The myth of a grasping homo economicus, he argued, is a fundamental misconception of human nature. Marx’s Das Kapital would not appear until seven years later.

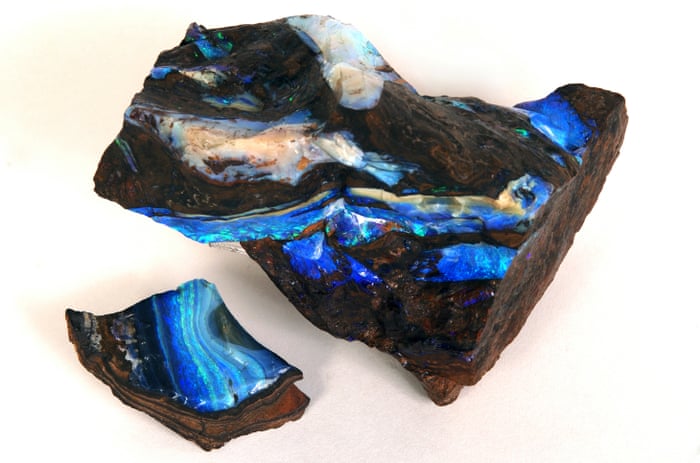

At the heart of this celebration of Ruskin’s 200th anniversary – he was born in 1819, the same year as Queen Victoria – is a telling story of his generous, ardent spirit. In 1875, Ruskin created a museum for the people of Sheffield. The north remembers: this show has been created by Sheffield’s museums together with the Ruskinian Guild of St George. Art, Ruskin believed, was for everyone. And everyone needs it. The industrial working class deserved not just bread but beauty. The most beautiful thing in this exhibition, however, is not a work of art. It’s the collection of minerals Ruskin presented to his people’s museum. These gorgeous rocks set this exhibition alight with their strong colours and brilliant crystal facets: purple amethyst, snow-white quartz, bubbling haematite.

And there, in a nutshell, is the reason for today’s Ruskin revival. In the late 20th century, Ruskin was considered a bit of a joke. Even now, his name for many people evokes a sexually repressed Victorian oddball. Even the curators of this loving homage can’t resist telling us how working-class audiences laughed at his “megaphone” lecturing voice and quirky bird imitations. Yet as the deepest crisis of capitalism since the 1930s drags on and Victorian critics of the cash nexus, from Karl Marx to William Morris, are taken seriously once more, Ruskin’s social radicalism looks urgent again. He was ahead of them all. In 1860, he horrified readers of the Cornhill magazine with a series of articles that denounced free-market economics. The myth of a grasping homo economicus, he argued, is a fundamental misconception of human nature. Marx’s Das Kapital would not appear until seven years later.

At the heart of this celebration of Ruskin’s 200th anniversary – he was born in 1819, the same year as Queen Victoria – is a telling story of his generous, ardent spirit. In 1875, Ruskin created a museum for the people of Sheffield. The north remembers: this show has been created by Sheffield’s museums together with the Ruskinian Guild of St George. Art, Ruskin believed, was for everyone. And everyone needs it. The industrial working class deserved not just bread but beauty. The most beautiful thing in this exhibition, however, is not a work of art. It’s the collection of minerals Ruskin presented to his people’s museum. These gorgeous rocks set this exhibition alight with their strong colours and brilliant crystal facets: purple amethyst, snow-white quartz, bubbling haematite.

Opal stones … ‘These gorgeous rocks set this exhibition alight with their strong colours and brilliant crystal facets’ Photograph: Hazel Drummond/Collection of the Guild of St George/Museums Sheffield

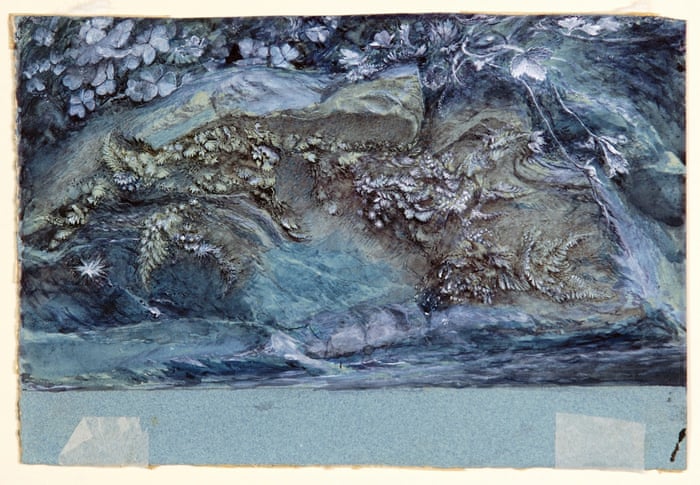

He created his little museum in a former cottage in Walkley, between Sheffield and its surrounding countryside, to draw working folk out of the smoky town to explore nature. For Ruskin, the natural world was sacred. To be in it was to be enraptured, transformed, redeemed. His responses to the natural are on display in his drawings and watercolours of glaciers and mossy riverbanks, wildflowers and a bright blue peacock feather. His eye for nature can be enthralling, especially when he homes in on strange gothic patterns and textures. His Study of Moss, Fern and Wood-Sorrel, Upon a Rocky River Bank is a mesmerising portrayal of green life entwined in the ancient scars and turbulent strata of a steep rocky mass.

Here is another way Ruskin suddenly looks contemporary again. There are new images of nature among the Victorian drawings, including a chilling digital analysis of the changing forms of Alpine glaciers by Dan Holdsworth. Ruskin knew nothing of global warming, but his passionate belief in the preciousness of nature comes through in his awestruck Turneresque watercolour of Vevey in the Alps, with its sapphire, immemorial mountains.

Study of Moss, Fern and Wood -Sorrel, upon a Rocky River Bank, 1875-79. Photograph: Hazel Drummond/© Collection of the Guild of St George / Museums Sheffield

What the show can’t fully reveal, because it is hidden by the precision of his drawings, is the tragedy of Ruskin’s passion for nature. Brought up as an evangelical Christian, shaped by the glories of art and nature he saw on childhood trips in Europe, his vocation as a young man was to teach his contemporaries to see the divinely created beauty of the world. “I have to prove to them ... that the truth of nature is part of the truth of God,” he wrote. As those lovely rocks in this exhibition show, geology was at the heart of his theocratic scientific vision. Yet geology in the 19th century was the very science that was demolishing god, fossil by fossil. By 1851, he could hear the geologists’ hammers chipping away his faith: “…those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.”

Ruskin’s scientific honesty devastated his Christian belief and that may have helped to destroy his reason. His calm drawings disguise a turbulence that was tearing him apart. His socialism, too, emerged in the later part of his life. In the Victorian hymn All Things Bright and Beautiful, the social order is seen as divinely appointed. But if there’s no God, Ruskin saw, why should the poor wait at the rich man’s gate?

This exhibition is a timely reminder of the tortured genius of the most complex and gifted art critic who ever lived – although it shows how inadequate any label is for this lofty soul.

• John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing is at Two Temple Place, London, from 26 January until 22 April.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jan/24/john-ruskin-the-power-of-seeing-review-critic-social-reformer-two-temple-place

John Ruskin

The Power of Seeing

26th January 2019 – 22nd April 2019

Artist, art critic, educator, social thinker and true polymath, John Ruskin (1819-1900) devoted his life to the pursuit of knowledge. To mark the bicentenary of his birth, a new exhibition produced by Two Temple Place, Museums Sheffield and the Guild of St George, will celebrate the legacy and enduring relevance of Ruskin’s ideas and vision. John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing will bring together over 190 paintings, drawings, daguerreotypes, metal work, and plaster casts to illustrate how Ruskin’s attitude to aesthetic beauty shaped his radical views on culture and society.

The exhibition will showcase significant objects from Sheffield’s Guild of St George Ruskin Collection whilst also drawing on the rich collections of both regional and national public museums and galleries, including, The Ashmolean; Calderdale Museums; The Fitzwilliam; Gallery Oldham; The Ruskin Library, Lancaster; Leeds Museums and Art Gallery; Tate; Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village and the William Morris Gallery. Newly commissioned works including site-specific installations by Timorous Beasties and Grizedale Arts, a new moving image piece by Dan Holdsworth and contributions from artists Hannah Downing and Emilie Taylor will also feature, exploring Ruskin’s contemporary legacy.

The exhibition is curated by Louise Pullen, Ruskin Curator at Museums Sheffield, with the support of Alison Morton, Exhibition & Displays Curator, Museums Sheffield. Author and journalist, Michael Glover has provided further interpretation and insight.

John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing will be complemented by a further exhibition continuing the bicentenary celebrations at the Millennium Gallery, Sheffield from 29 May – 15 September 2019.

Ruskin To-Day is a gathering of the many people, places and enterprises devoted to Ruskin and his work. For more on all the activity planned around the world for 2019, go to www.ruskin200.com.

The exhibition is supported by the Garfield Weston Foundation, Foyle Foundation, Sheffield Town Trust and James Neill Trust Fund.

John Ruskin

The Power of Seeing

26th January 2019 – 22nd April 2019

Artist, art critic, educator, social thinker and true polymath, John Ruskin (1819-1900) devoted his life to the pursuit of knowledge. To mark the bicentenary of his birth, a new exhibition produced by Two Temple Place, Museums Sheffield and the Guild of St George, will celebrate the legacy and enduring relevance of Ruskin’s ideas and vision. John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing will bring together over 190 paintings, drawings, daguerreotypes, metal work, and plaster casts to illustrate how Ruskin’s attitude to aesthetic beauty shaped his radical views on culture and society.

The exhibition will showcase significant objects from Sheffield’s Guild of St George Ruskin Collection whilst also drawing on the rich collections of both regional and national public museums and galleries, including, The Ashmolean; Calderdale Museums; The Fitzwilliam; Gallery Oldham; The Ruskin Library, Lancaster; Leeds Museums and Art Gallery; Tate; Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village and the William Morris Gallery. Newly commissioned works including site-specific installations by Timorous Beasties and Grizedale Arts, a new moving image piece by Dan Holdsworth and contributions from artists Hannah Downing and Emilie Taylor will also feature, exploring Ruskin’s contemporary legacy.

The exhibition is curated by Louise Pullen, Ruskin Curator at Museums Sheffield, with the support of Alison Morton, Exhibition & Displays Curator, Museums Sheffield. Author and journalist, Michael Glover has provided further interpretation and insight.

John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing will be complemented by a further exhibition continuing the bicentenary celebrations at the Millennium Gallery, Sheffield from 29 May – 15 September 2019.

Ruskin To-Day is a gathering of the many people, places and enterprises devoted to Ruskin and his work. For more on all the activity planned around the world for 2019, go to www.ruskin200.com.

The exhibition is supported by the Garfield Weston Foundation, Foyle Foundation, Sheffield Town Trust and James Neill Trust Fund.

Monday, 28 January 2019

Sunday, 27 January 2019

Saturday, 26 January 2019

Wednesday night's set lists at The Habit, York

Ron Elderly: -

Make You Feel My Love

You Better Move On

Da Elderly: -

Mellow My Mind

Out On The Weekend

On a raw night in York, The Habit was unexpectedly full at the start of the open mic session, but there wasn't a surfeit of players. It was good to have Ron back from his flu-like bug. As time wore on folks drifted away, presumably to the comfort of their firesides! Some players came back for a second turn, but by about 11pm there were only a few people left in the bar. I suggested we ditch the open mic and have a jam/sing along - so the 3 or 4 of us left to play sat around and had a great time trading songs until closing time.

Songs played included: -

The River

Love Is The Sweetest Thing

Country Roads

Lola

Twilight Time

Sweet Virginia

I Don't Want To Talk About It

Put The Message In The Box

She's The One

Wrecking Ball

Make You Feel My Love

You Better Move On

Da Elderly: -

Mellow My Mind

Out On The Weekend

On a raw night in York, The Habit was unexpectedly full at the start of the open mic session, but there wasn't a surfeit of players. It was good to have Ron back from his flu-like bug. As time wore on folks drifted away, presumably to the comfort of their firesides! Some players came back for a second turn, but by about 11pm there were only a few people left in the bar. I suggested we ditch the open mic and have a jam/sing along - so the 3 or 4 of us left to play sat around and had a great time trading songs until closing time.

Songs played included: -

The River

Love Is The Sweetest Thing

Country Roads

Lola

Twilight Time

Sweet Virginia

I Don't Want To Talk About It

Put The Message In The Box

She's The One

Wrecking Ball

Friday, 25 January 2019

Dead Poets Society #89 Hart Crane: Chaplinesque

We will make our meek adjustments,

Contented with such random consolations

As the wind deposits

In slithered and too ample pockets.

For we can still love the world, who find

A famished kitten on the step, and know

Recesses for it from the fury of the street,

Or warm torn elbow coverts.

We will sidestep, and to the final smirk

Dally the doom of that inevitable thumb

That slowly chafes its puckered index toward us,

Facing the dull squint with what innocence

And what surprise!

And yet these fine collapses are not lies

More than the pirouettes of any pliant cane;

Our obsequies are, in a way, no enterprise.

We can evade you, and all else but the heart:

What blame to us if the heart live on.

The game enforces smirks; but we have seen

The moon in lonely alleys make

A grail of laughter of an empty ash can,

And through all sound of gaiety and quest

Have heard a kitten in the wilderness.

Thursday, 24 January 2019

Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World

Link Wray

RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World is a feature documentary about the role of Native Americans in popular music history.

Many artists and musical forms played a role in the creation of rock, but arguably no single piece of music was more influential than the 1958 instrumental “Rumble” by American Indian rock guitarist and singer/songwriter Link Wray.

When recalling Link Wray’s shivering guitar classic, “Rumble,” Martin Scorsese marvels, “It is the sound of that guitar . . . that aggression.” "Rumble" was the first song to use distortion and feedback. It introduced the rock power chord – and was one of the very few instrumental singles to be banned from the radio for fear it would incite violence.

RUMBLE explores how the Native American influence is an integral part of music history, despite attempts to ban, censor, and erase Indian culture in the United States.

As RUMBLE reveals, the early pioneers of the blues had Native as well as African American roots, and one of the first and most influential jazz singers’ voices was trained on Native American songs. As the folk rock era took hold in the 60s and 70s, Native Americans helped to define its evolution.

Father of the Delta Blues Charley Patton, influential jazz singer Mildred Bailey, metaphysical guitar wizard Jimi Hendrix, and folk heroine Buffy Sainte-Marie are among the many music greats who have Native American heritage and have made their distinctive mark on music history. For the most part, their Indian heritage was unknown.

RUMBLE uses playful re-creations and little-known stories, alongside concert footage, archives and interviews. The stories of these iconic Native musicians are told by some of America’s greatest music legends who knew them, played music with them, and were inspired by them: everyone from Buddy Guy, Quincy Jones, and Tony Bennett to Iggy Pop, Steven Tyler, and Stevie Van Zandt.

RUMBLE shows how Indigenous music was part of the very fabric of American popular music from the beginning, but that the Native American contribution was left out of the story – until now.

https://www.rumblethemovie.com/about

Jesse Ed Davis

An Encore for the Native Americans Who Shook Up Rock ’n’ Roll

By Robert Ito

The New York Times

31 July 2017

Plenty of rock ’n’ roll songs have been banned from the airwaves because of their lyrics, but “Rumble” was the first to be banned because of its very sound. Recorded by Link Wray & His Ray Men in 1958, the instrumental pioneered the use of distortion, feedback and the power chord, a mix that made stations in New York and Boston so nervous they refused to play the song for fear that it might incite violence. According to popular lore, the hit song got its name because it reminded listeners of a gang fight, or at least a musical invitation to one; in “Pulp Fiction,” it’s the tune that plays while Uma Thurman and John Travolta share a $5 milkshake and a tense silence.

“If you considered yourself a real rock ’n’ roll guitar player, you had to learn ‘Rumble,’” Robbie Robertson, the songwriter and guitarist, said in an interview. “It was raw and dirty, and had that rebellious spirit to it.”

The single is at the heart of “Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World,” a documentary directed by the Canadian filmmakers Catherine Bainbridge and Alfonso Maiorana that has scooped up prizes on the festival circuit, including a Sundance special jury award for “masterful storytelling.” Reviewing the film for The Times, Ken Jaworowski likened it to the Oscar-winning “20 Feet From Stardom” and “Searching for Sugar Man.”

31 July 2017

Plenty of rock ’n’ roll songs have been banned from the airwaves because of their lyrics, but “Rumble” was the first to be banned because of its very sound. Recorded by Link Wray & His Ray Men in 1958, the instrumental pioneered the use of distortion, feedback and the power chord, a mix that made stations in New York and Boston so nervous they refused to play the song for fear that it might incite violence. According to popular lore, the hit song got its name because it reminded listeners of a gang fight, or at least a musical invitation to one; in “Pulp Fiction,” it’s the tune that plays while Uma Thurman and John Travolta share a $5 milkshake and a tense silence.

“If you considered yourself a real rock ’n’ roll guitar player, you had to learn ‘Rumble,’” Robbie Robertson, the songwriter and guitarist, said in an interview. “It was raw and dirty, and had that rebellious spirit to it.”

The single is at the heart of “Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World,” a documentary directed by the Canadian filmmakers Catherine Bainbridge and Alfonso Maiorana that has scooped up prizes on the festival circuit, including a Sundance special jury award for “masterful storytelling.” Reviewing the film for The Times, Ken Jaworowski likened it to the Oscar-winning “20 Feet From Stardom” and “Searching for Sugar Man.”

In theaters in the United States and Canada now, “Rumble” explores the history of Native Americans in popular music, some celebrated for their work, others less so. Jesse Ed Davis, who played alongside the Rolling Stones and, over time, every one of the Beatles, is here, as is Buffy Sainte-Marie, the protest singer who composed songs about everything from young love and spirituality to cultural genocide and the theft of Indian lands. Jimi Hendrix, whose paternal grandmother was one-quarter Cherokee, appears, resplendent in a white beaded jacket and moccasins, at Woodstock, as does the jazz singer Mildred Bailey, whom a young Bing Crosby credited with giving him his start.

Mildred Bailey

And then there’s Wray, whose song and sound went on to inspire musicians from Pete Townshend and Neil Young to Iggy Pop and MC5. “It wasn’t till later on that I found out that Link Wray was an Indian,” of Shawnee heritage, said Mr. Robertson, who learned to play guitar on the Six Nations reserve in Ontario. “It just made the whole thing 10 times cooler to me.”

Jesse Ed Davis, right, backing George Harrison at the Concert for Bangladesh in 1971

One of the most striking aspects of the documentary is how few people, like Mr. Robertson, knew that these artists were Indians at all. Stevie Salas, an executive producer of the film who got his start playing electric guitar behind Rod Stewart and Bootsy Collins, recalled watching scenes of Mr. Davis playing in the 1972 documentary about George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh. “I’ve watched that footage a million times,” said Mr. Salas, who is Apache, “and all of a sudden I was like, how did I not notice the big, 6-foot Indian standing next to Eric Clapton?”

For every Redbone, the ’70s rockers who openly embraced their Indian roots, there were dozens of others who did not. For many, there was little upside to it. “Around the time when ‘Rumble’ came out, there was the Hayes Pond incident, where this Grand Dragon was preaching from the backs of trucks about the ‘mongrelization’ of white people by American Indians,” Ms. Bainbridge said, referring to a North Carolina confrontation between the Klan and the Lumbee. “Link Wray grew up in the center of all that, as did Native Americans throughout the South.”

The film was inspired by “Up Where We Belong: Native Musicians in Popular Culture,” an exhibition that was first mounted at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in 2010. It soon became one of the museum’s most popular. Curated by Mr. Salas and Tim Johnson, the museum’s program director at the time, the exhibition, with its rock videos and battle-ax guitars, was a marked departure from previous shows. “They certainly didn’t want to include Randy Castillo, the drummer from Ozzy Osbourne,” Mr. Salas said.

Buoyed by the success of the show and the stories the Smithsonian was able to uncover, the curators immediately thought: This needs to be a documentary. They sought out Ms. Bainbridge, who had gotten critical acclaim for the 2009 documentary “Reel Injun.” That film examined the portrayal of Native Americans in Hollywood, many of them played by nonnative actors. “We found this way, through humor, for people to relate,” she said. “I thought we’d never have that chance again, to make a film that could really cross over. But as it turns out, music is even more powerful than comedy.”

Throughout, the film reveals how Native American rhythms and stylings became a part of the larger tapestry of American music. In one scene, the poet and musician Joy Harjo (“Crazy Brave”) explains how the call and response of Muscogee music influenced the evolution of jazz and blues; in another, the singer-songwriter Pura Fe connects the blues guitar and vocal inflections of Charley Patton, who was probably of Choctaw ancestry, with traditional Indian music.

One of the most striking aspects of the documentary is how few people, like Mr. Robertson, knew that these artists were Indians at all. Stevie Salas, an executive producer of the film who got his start playing electric guitar behind Rod Stewart and Bootsy Collins, recalled watching scenes of Mr. Davis playing in the 1972 documentary about George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh. “I’ve watched that footage a million times,” said Mr. Salas, who is Apache, “and all of a sudden I was like, how did I not notice the big, 6-foot Indian standing next to Eric Clapton?”

For every Redbone, the ’70s rockers who openly embraced their Indian roots, there were dozens of others who did not. For many, there was little upside to it. “Around the time when ‘Rumble’ came out, there was the Hayes Pond incident, where this Grand Dragon was preaching from the backs of trucks about the ‘mongrelization’ of white people by American Indians,” Ms. Bainbridge said, referring to a North Carolina confrontation between the Klan and the Lumbee. “Link Wray grew up in the center of all that, as did Native Americans throughout the South.”

The film was inspired by “Up Where We Belong: Native Musicians in Popular Culture,” an exhibition that was first mounted at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in 2010. It soon became one of the museum’s most popular. Curated by Mr. Salas and Tim Johnson, the museum’s program director at the time, the exhibition, with its rock videos and battle-ax guitars, was a marked departure from previous shows. “They certainly didn’t want to include Randy Castillo, the drummer from Ozzy Osbourne,” Mr. Salas said.

Buoyed by the success of the show and the stories the Smithsonian was able to uncover, the curators immediately thought: This needs to be a documentary. They sought out Ms. Bainbridge, who had gotten critical acclaim for the 2009 documentary “Reel Injun.” That film examined the portrayal of Native Americans in Hollywood, many of them played by nonnative actors. “We found this way, through humor, for people to relate,” she said. “I thought we’d never have that chance again, to make a film that could really cross over. But as it turns out, music is even more powerful than comedy.”

Throughout, the film reveals how Native American rhythms and stylings became a part of the larger tapestry of American music. In one scene, the poet and musician Joy Harjo (“Crazy Brave”) explains how the call and response of Muscogee music influenced the evolution of jazz and blues; in another, the singer-songwriter Pura Fe connects the blues guitar and vocal inflections of Charley Patton, who was probably of Choctaw ancestry, with traditional Indian music.

Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson playing electric guitars at a White Plains, N.Y., concert in 1966

And then there are the stories in the film that are pure rock ’n’ roll. Mr. Robertson recalls his world tour with the newly electric Bob Dylan in 1966, when angry audiences blamed Mr. Robertson and the rest of the Band for tainting their golden child. “All over North America, all over Australia, all over Europe, every night, they booed us,” he said. But he remembers telling Mr. Dylan: “They’re wrong. This is good. I’m sorry, but the world is wrong, and we’re right.”

In the end, a lot of the stories are like this, small triumphs over overwhelming odds, which was what the filmmakers intended all along. “I didn’t want to make a victim film,” Mr. Salas said. “Some of my Native friends were adamant too, saying, we’ve had enough of these films where they took this from us, they did this to us. We were like, no, let’s talk about these amazing people who did these amazing things.”

And then there are the stories in the film that are pure rock ’n’ roll. Mr. Robertson recalls his world tour with the newly electric Bob Dylan in 1966, when angry audiences blamed Mr. Robertson and the rest of the Band for tainting their golden child. “All over North America, all over Australia, all over Europe, every night, they booed us,” he said. But he remembers telling Mr. Dylan: “They’re wrong. This is good. I’m sorry, but the world is wrong, and we’re right.”

In the end, a lot of the stories are like this, small triumphs over overwhelming odds, which was what the filmmakers intended all along. “I didn’t want to make a victim film,” Mr. Salas said. “Some of my Native friends were adamant too, saying, we’ve had enough of these films where they took this from us, they did this to us. We were like, no, let’s talk about these amazing people who did these amazing things.”

Tuesday, 22 January 2019

Monday, 21 January 2019

Paddy McAloon at 60

PADDY MCALOON AT 60 [GOING ON 61]

The Blackpool Sentinel

29 January 2018

From the gawkily posed photographs that have survived the decades, its clear they stood steadfastly out of step with their peers and, you’d think, knew that much best themselves. But although Prefab Sprout’s shape and style has evolved out of all recognition in the years since 1977, it’s that same sense of mis-match – the uneasy young buck in an out-sized dinner jacket and cheap shades – which has consistently defined them through the many moons and their many moods since.

Beyond the obvious, much of the band’s story is still soaked in loose talk and urban myth. Music’s mainstream, with which they flirted briefly, gave up on them twenty odd years ago and, ever since, the gaps in Prefab Sprout’s narrative have been filled by obsessive, fan-fuelled levels of hearsay, suggestion and general tattle. But nothing really changes there, either :- the band’s frontman and writer, Paddy McAloon – the eldest son of an Irish Catholic immigrant family – was initially presented as a former seminarian.

What we do know for certain is that McAloon’s band first took root in the small village of Witton Gilbert in the North East of England, seventeen miles from Newcastle, during a peculiar period in British music history. The Clash had released their first album, The Sex Pistols had hi-jacked the Queen’s silver jubilee year – 1977 – and unofficially sound-tracked it while disco was approaching it’s commercial and creative pomp, flirting increasingly in the margins with electronica as it went. By the end of the following year, The Bee Gees were out-selling the field and Sid Vicious was arrested in New York for the murder of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen.

Worlds away in every respect, Paddy McAloon was twenty years old and lugging Prefab Sprout’s improbably ambitious songs – and the group’s cheap equipment – out into a variety of pub venues around County Durham for the first time. The band had been in gestation for years – in theory, in dreams – and although Paddy’s earliest hand-drawn outlines were far removed from the gormless aspects of punk rock or the sleazy veneer of cheap disco, he was certainly propelled forward by the more irresistible forces of both codes...

...Knowing little else, I thought that all of my formative pet sounds were peerless which, I suppose, is exactly as it should be during those first unsuspecting meets with the heady power of song. But while I know now that Teenage Fanclub borrowed influences freely – from Big Star, most obviously – and that Into Paradise magpied likewise from The Sound, its just impossible for me to clearly trace Paddy McAloon’s form lines. Prefab Sprout’s first single, ‘Lions In My Own Garden [Exit Someone]’ and debut album, ‘Swoon’, sound like what and sound like whom ? Aztec Camera ? Steely Dan ? XTC ? Mike Oldfield ? All of the above and nothing on earth ?

Which is all the more baffling given that no modern songwriter – to my mind, at least – has dropped so many references to music, writers and musicians so deeply inside his or her own material. Is there another contemporary writer for whom songs and the transcendence of sound have been celebrated so explicitly across such a vast body of work ? A career that now spans thirty-six years and nine studio albums.

From the very earliest Prefab Sprout songs – ‘Faron Young’ and ‘Radio Love’ were staples in their first live sets – to ‘Mysterious’ and ‘The Songs Of Danny Galway’ on 2013’s ‘Crimson Red’ album, McAloon has consistently used the pull of the of song and the craft of the writer as one of his primary lyrical motifs. ‘Hallelujah’, ‘The Devil Has All The Best Tunes’, ‘Donna Summer’, ‘I Love Music’, ‘The Wedding March’, ‘Nero The Zero’, ‘Electric Guitars’, ‘Nightingales’ and the imperious ‘Doo Wop In Harlem’ ;- the references are as manifold as they are varied and widely spread...

...Forty years after the band committed it’s first original songs to tape in the cramped confines of a custom-designed studio attached to the music department at a local college, Prefab Sprout remain very much an acquired taste, although no less intriguing or enigmatic for that. Indeed the most recent McAloon composition to see the light of day is an evocative protest ballad called ‘America’, possibly recorded on a smart phone or a small camcorder, and posted up onto YouTube ten months ago by Prefab Sprout’s long-time manager, Keith Armstrong.

Performed by Paddy on acoustic guitar in what, for the last decade, have been his trademark duds – trilby hat and shades, off-set with long grey hair and a full beard – ‘America’ is absolutely bulls-eye Prefab Sprout. Over a series of gentle progressions, McAloon works his fingers into almost impossible positions along the fret-board, effortlessly filling the spaces with unlikely moves, his voice as familiar as ever as he begs of America ;– ‘don’t reject the stranger knocking at your door’. To long-time band watchers, the song’s unheralded appearance on-line was a tender reassurance that yes, work was still ongoing at Andromeda Heights, McAloon’s home studio where, legend has it, decades of unreleased songs and albums remain under lock and key...

...Paddy and myself : our destinies had been inter-twined for fifteen years. As with most of the best and most important things in life, I’d first come across Prefab Sprout during the early 1980s on both Dave Fanning’s ‘Rock Show’ on RTÉ radio and on David Heffernan’s Saturday lunchtime music slot on the RTÉ One youth television strand, ‘Anything Goes’. [As an aside for anoraks, its worth noting that it was also on this slot that I was first introduced to Thomas Dolby’s magnificent ‘Airwaves’].

My love for Prefab Sprout was instant and unquestioning :- windswept, lispy and smart, they stood tall on Marsden Rock, a National Trust-owned coastal site on South Shields, where they performed ‘Don’t Sing’, miles removed from the sounds du jour.*

And although the band’s earliest shows in Ireland – their 1983 stop-off at The Buttery in Trinity College and a support to Paul Brady in Belfast the following year – were out of bounds to me on the grounds of age and distance, I was there, in thrall, when they played The Point Theatre in Dublin on the ‘Jordan : The Comeback’ tour in December, 1990. Supported on the night by one of my favourite local bands, Hinterland, Prefab Sprout were bulked up for the duration of that tour and, playing as a seven piece and with McAloon leading the line in a white suit, covered a huge amount of ground over the course of a mammoth set...

...To this end, the liner notes Paddy penned for ‘Let’s Change The World With Music’, are especially significant, I think. The songs that comprise this record were originally written and recorded as an intended follow-up to 1990’s vast double album, ‘Jordan : The Comeback’ and, for reasons we can assume have more to do with record company direction or lack of it, went unreleased for fifteen years, during which time the writer moved on as clinically as he’s always done.

‘It goes without saying that I would have liked to have recorded ‘Let’s Change The World With Music’ with Marty, Wendy, Neil and Thomas [Dolby]. I believe they wanted to, but we missed our moment and it wasn’t to be. Why ? I have no idea. Beats me. Anyway, one day in May, ’93, we made a bad move. But hey, water under the bridge’. McAloon eventually put the record together on his own, with technical help from Calum Malcolm.

Another of Paddy’s party pieces is his long-standing capacity to de-rail his own interviews by talking freely and in-depth about the music and the merits of others. He does this on the ‘Let’s Change’ sleeve-notes too, where he gushes at length about the mythical Beach Boys album, ‘Smile’. And he concludes those notes by observing that ‘the ‘Smile myth is only partly to do with music. It’s also about the dull, grey stuff that musicians are often slow to address, yet ignore at their peril. And it may even have something to say about ego ; about blithely, and unrealistically assuming that everyone sees things the way you do. But ultimately, it is probably just a story about entropy ; the natural tendency for all things – however lovely – to eventually fly apart’.

Tellingly, the record is dedicated ‘for robust and unsentimental reasons’ to Martin McAloon, Wendy Smith, Neil Conti, Thomas Dolby and Michael Salmon [the band’s first drummer]. For the good times’...

Read the full article here:

From the gawkily posed photographs that have survived the decades, its clear they stood steadfastly out of step with their peers and, you’d think, knew that much best themselves. But although Prefab Sprout’s shape and style has evolved out of all recognition in the years since 1977, it’s that same sense of mis-match – the uneasy young buck in an out-sized dinner jacket and cheap shades – which has consistently defined them through the many moons and their many moods since.

Beyond the obvious, much of the band’s story is still soaked in loose talk and urban myth. Music’s mainstream, with which they flirted briefly, gave up on them twenty odd years ago and, ever since, the gaps in Prefab Sprout’s narrative have been filled by obsessive, fan-fuelled levels of hearsay, suggestion and general tattle. But nothing really changes there, either :- the band’s frontman and writer, Paddy McAloon – the eldest son of an Irish Catholic immigrant family – was initially presented as a former seminarian.

What we do know for certain is that McAloon’s band first took root in the small village of Witton Gilbert in the North East of England, seventeen miles from Newcastle, during a peculiar period in British music history. The Clash had released their first album, The Sex Pistols had hi-jacked the Queen’s silver jubilee year – 1977 – and unofficially sound-tracked it while disco was approaching it’s commercial and creative pomp, flirting increasingly in the margins with electronica as it went. By the end of the following year, The Bee Gees were out-selling the field and Sid Vicious was arrested in New York for the murder of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen.

Worlds away in every respect, Paddy McAloon was twenty years old and lugging Prefab Sprout’s improbably ambitious songs – and the group’s cheap equipment – out into a variety of pub venues around County Durham for the first time. The band had been in gestation for years – in theory, in dreams – and although Paddy’s earliest hand-drawn outlines were far removed from the gormless aspects of punk rock or the sleazy veneer of cheap disco, he was certainly propelled forward by the more irresistible forces of both codes...

...Knowing little else, I thought that all of my formative pet sounds were peerless which, I suppose, is exactly as it should be during those first unsuspecting meets with the heady power of song. But while I know now that Teenage Fanclub borrowed influences freely – from Big Star, most obviously – and that Into Paradise magpied likewise from The Sound, its just impossible for me to clearly trace Paddy McAloon’s form lines. Prefab Sprout’s first single, ‘Lions In My Own Garden [Exit Someone]’ and debut album, ‘Swoon’, sound like what and sound like whom ? Aztec Camera ? Steely Dan ? XTC ? Mike Oldfield ? All of the above and nothing on earth ?

Which is all the more baffling given that no modern songwriter – to my mind, at least – has dropped so many references to music, writers and musicians so deeply inside his or her own material. Is there another contemporary writer for whom songs and the transcendence of sound have been celebrated so explicitly across such a vast body of work ? A career that now spans thirty-six years and nine studio albums.

From the very earliest Prefab Sprout songs – ‘Faron Young’ and ‘Radio Love’ were staples in their first live sets – to ‘Mysterious’ and ‘The Songs Of Danny Galway’ on 2013’s ‘Crimson Red’ album, McAloon has consistently used the pull of the of song and the craft of the writer as one of his primary lyrical motifs. ‘Hallelujah’, ‘The Devil Has All The Best Tunes’, ‘Donna Summer’, ‘I Love Music’, ‘The Wedding March’, ‘Nero The Zero’, ‘Electric Guitars’, ‘Nightingales’ and the imperious ‘Doo Wop In Harlem’ ;- the references are as manifold as they are varied and widely spread...

...Forty years after the band committed it’s first original songs to tape in the cramped confines of a custom-designed studio attached to the music department at a local college, Prefab Sprout remain very much an acquired taste, although no less intriguing or enigmatic for that. Indeed the most recent McAloon composition to see the light of day is an evocative protest ballad called ‘America’, possibly recorded on a smart phone or a small camcorder, and posted up onto YouTube ten months ago by Prefab Sprout’s long-time manager, Keith Armstrong.

Performed by Paddy on acoustic guitar in what, for the last decade, have been his trademark duds – trilby hat and shades, off-set with long grey hair and a full beard – ‘America’ is absolutely bulls-eye Prefab Sprout. Over a series of gentle progressions, McAloon works his fingers into almost impossible positions along the fret-board, effortlessly filling the spaces with unlikely moves, his voice as familiar as ever as he begs of America ;– ‘don’t reject the stranger knocking at your door’. To long-time band watchers, the song’s unheralded appearance on-line was a tender reassurance that yes, work was still ongoing at Andromeda Heights, McAloon’s home studio where, legend has it, decades of unreleased songs and albums remain under lock and key...

...Paddy and myself : our destinies had been inter-twined for fifteen years. As with most of the best and most important things in life, I’d first come across Prefab Sprout during the early 1980s on both Dave Fanning’s ‘Rock Show’ on RTÉ radio and on David Heffernan’s Saturday lunchtime music slot on the RTÉ One youth television strand, ‘Anything Goes’. [As an aside for anoraks, its worth noting that it was also on this slot that I was first introduced to Thomas Dolby’s magnificent ‘Airwaves’].

My love for Prefab Sprout was instant and unquestioning :- windswept, lispy and smart, they stood tall on Marsden Rock, a National Trust-owned coastal site on South Shields, where they performed ‘Don’t Sing’, miles removed from the sounds du jour.*

And although the band’s earliest shows in Ireland – their 1983 stop-off at The Buttery in Trinity College and a support to Paul Brady in Belfast the following year – were out of bounds to me on the grounds of age and distance, I was there, in thrall, when they played The Point Theatre in Dublin on the ‘Jordan : The Comeback’ tour in December, 1990. Supported on the night by one of my favourite local bands, Hinterland, Prefab Sprout were bulked up for the duration of that tour and, playing as a seven piece and with McAloon leading the line in a white suit, covered a huge amount of ground over the course of a mammoth set...

...To this end, the liner notes Paddy penned for ‘Let’s Change The World With Music’, are especially significant, I think. The songs that comprise this record were originally written and recorded as an intended follow-up to 1990’s vast double album, ‘Jordan : The Comeback’ and, for reasons we can assume have more to do with record company direction or lack of it, went unreleased for fifteen years, during which time the writer moved on as clinically as he’s always done.

‘It goes without saying that I would have liked to have recorded ‘Let’s Change The World With Music’ with Marty, Wendy, Neil and Thomas [Dolby]. I believe they wanted to, but we missed our moment and it wasn’t to be. Why ? I have no idea. Beats me. Anyway, one day in May, ’93, we made a bad move. But hey, water under the bridge’. McAloon eventually put the record together on his own, with technical help from Calum Malcolm.

Another of Paddy’s party pieces is his long-standing capacity to de-rail his own interviews by talking freely and in-depth about the music and the merits of others. He does this on the ‘Let’s Change’ sleeve-notes too, where he gushes at length about the mythical Beach Boys album, ‘Smile’. And he concludes those notes by observing that ‘the ‘Smile myth is only partly to do with music. It’s also about the dull, grey stuff that musicians are often slow to address, yet ignore at their peril. And it may even have something to say about ego ; about blithely, and unrealistically assuming that everyone sees things the way you do. But ultimately, it is probably just a story about entropy ; the natural tendency for all things – however lovely – to eventually fly apart’.

Tellingly, the record is dedicated ‘for robust and unsentimental reasons’ to Martin McAloon, Wendy Smith, Neil Conti, Thomas Dolby and Michael Salmon [the band’s first drummer]. For the good times’...

Read the full article here:

* Observed by a certain Terry Kelly

Sunday, 20 January 2019

Saturday, 19 January 2019

Dead Poets Society #88 Gerard Manley Hopkins: Windhover

Windhover by Gerard Manley Hopkins

To Christ Our Lord

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate's heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

Friday, 18 January 2019

Wednesday night's set lists at The Habit, York

Set 1:

Once An Angel

Need Your Love So Bad

Never Let Her Slip Away

Set 2:

I Don't Want To Talk About It

Harvest Moon

Ron threw a sickie with the virus that has caught out so many recently. Get well soon Ron!

During setup the place was virtually empty, but by the time we were ready to start it was absolutely heaving. Not having too many players initially meant that set lists were extended from the usual 2 to 3 songs. Highlight of the night was a young student from Japan who introduced himself as Ken, a drummer in a band back home, saying that he had been to The Habit a couple of weeks ago and had been inspired to play guitar. So after just 2 weeks practice he pitched up with an original song....in English....and carried it off perfectly - to a standing ovation. Open mic heaven. Once everyone had had a turn those remaining were asked if they would like to come back for another song. I was given the honour of closing the show (Set 2).

Once An Angel

Need Your Love So Bad

Never Let Her Slip Away

Set 2:

I Don't Want To Talk About It

Harvest Moon

Ron threw a sickie with the virus that has caught out so many recently. Get well soon Ron!

During setup the place was virtually empty, but by the time we were ready to start it was absolutely heaving. Not having too many players initially meant that set lists were extended from the usual 2 to 3 songs. Highlight of the night was a young student from Japan who introduced himself as Ken, a drummer in a band back home, saying that he had been to The Habit a couple of weeks ago and had been inspired to play guitar. So after just 2 weeks practice he pitched up with an original song....in English....and carried it off perfectly - to a standing ovation. Open mic heaven. Once everyone had had a turn those remaining were asked if they would like to come back for another song. I was given the honour of closing the show (Set 2).

Thursday, 17 January 2019

Tuesday, 15 January 2019

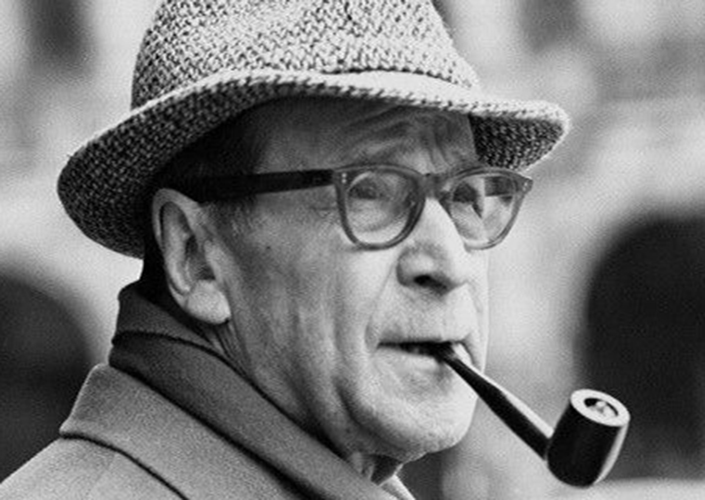

The Genius of Georges Simenon...

David Hare: the genius of Georges Simenon

As he brings one of the crime writer’s novels to the National stage, David Hare reveals why he loves the pithy, power-obsessed creator of MaigretDavid Hare

The Guardian

Sun 25 Sep 2016

Like many bookish children, I grew up consuming detective fiction more than any other kind. Even then I had noticed that stories supposedly driven by narrative depended for their real vitality on establishing ambience. Crime writing came to life when it had density, when you felt that the paint was being laid on thick. A strong sense of time and place was far more exciting than a clever puzzle. Anyone could create a mystery, but only the best could summon up a world in which the mystery could take root.

My taste in literary fiction – I read every word of Patrick Hamilton and Graham Greene – was towards those authors whose techniques most closely resembled those of thriller writers. When, at university, I came across WH Auden’s suggestion that Raymond Chandler’s books “should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art”, I was bewildered. It had never occurred to me that thrillers were anything less. By then I had already graduated from Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers to Dashiell Hammett and the chill ambiguity of Patricia Highsmith. But when I discovered that the author of the Maigret series – which I knew chiefly through the BBC television series with Rupert Davies – was also the author of stand-alone novels, my expectations of the genre changed and expanded. These books belonged more alongside Camus and Sartre than Arthur Conan Doyle. The popular joke in Le Canard enchaîné that “M Simenon makes his living by killing someone every month and then discovering the murderer” seemed nothing more than that. A joke.

It’s symptomatic of our misunderstanding of the unique Georges Simenon that so many people believe he was French. In fact, he was Belgian, born in Liège in 1903 and brought up in a poorly defined country that had often suffered under occupation. In Belgium, few people fostered illusions about national greatness. “Under occupation,” he wrote, “your overwhelming concern is with what you will eat.” Simenon’s background, and his lifelong feeling that he was disliked by his mother, left him with the aim of developing, equally as a writer and as a man, a wholly undeluded view of life. As he later observed: “It must be great to belong to a group, a nation, a class. It would give you a feeling of superiority. If you’re alone you’re not superior to anyone.” Or as he put it rather more bitterly: “During earthquakes and wars and floods and shipwrecks you see a love between men that you don’t see at any other time.”

In fact, he could hardly have been less French. What Frenchman or woman would speak of their loathing of gastronomy – “all that terrible fussing about what you eat”? What French writer or politician would agree that “every ideal ends in a fierce struggle against those who do not share it?” Simenon was particularly horrified by Charles de Gaulle’s pretence that the French had won the war. The untruth offended him. Simenon believed the events of the 1930s and 40s had defeated the French as thoroughly as they had the Germans. “I’ve ceased to believe in evil, only in illness. Nixon believes he’s the champion of the United States, De Gaulle the rebuilder of France. Yet nobody locks them up. Those who invent morals, who define them and impose them, end up believing in them. We’re all hopeless prisoners of what we choose to believe.”

Simenon, not prone to grand literary statements, once said that he wanted to write like Sophocles or Euripides. Over and again, he describes someone quietly living their life, until some random fait divers – a road accident, a heart attack, an inheritance – brings out a fatal element in their character that trips them up. Striking out towards freedom, they fall instead into captivity. He had the idea that a book, like a Greek tragedy, should be experienced in a single session. “You can’t see a tragedy in more than one sitting.” Serial killers, soon to become the thundering cliches of modern drama, whether speaking Danish, Swedish or English, would have held no appeal for Simenon precisely because they are, by definition, extraordinary – and considerably less common in life than on television. Typically, in one of Simenon’s stories, a single crime is enough to ensure that a hitherto normal life falls apart, with no notice, as though any of us might at any time suddenly encounter a crisis that we will turn out to be powerless to overcome.

The thrill of reading a novel, said Simenon, is to “look through the keyhole to see if other people have the same feelings and instincts you do”. The man who, when adolescent, says he suffered physical pain at the idea that there could be so many women who would escape him, has the intense focus of a voyeur. An ex-journalist, he often describes towns from their canals or railway lines, because from there you could look into the back of residents’ lives and not be deceived by the front. He may have said “Other people collect stamps, I collect human beings”, but remarkably he refuses at all times to pass judgment on anyone. “You will find no priests in my work!” Not only does Simenon take care to exclude politics, religion, history and philosophy from his character’s dialogue and thoughts, but the deadpan flatness of his prose style and his bare-bone vocabulary create a disturbing absence of moral control. “Fifty years ago people had answers, now they don’t.”

It was this fallen universe of compromise that I found so convincing when I was growing up. It matched what I had already seen of life. I knew at first hand that Simenon was right when he said that “the criminal is often less guilty than his victim”. But it was only when I was older that I became addicted to the hard stuff – the unsparing novels that take his fatalistic view to its ultimate. If, as is generally thought, Simenon wrote around 400 books, then about 117 are serious novels, the romans durs that meant most to him. André Gide, one of his many literary admirers, when asked which of Simenon’s books a beginner should read first, famously replied: “All of them.” But to my own taste, Simenon’s most searching work came out of his queasy, compromised time in occupied France, and in his desperate hunt thereafter for personal happiness in heavy-drinking exile in the US. If you want to read three of his greatest books, try the deceptively light Sunday, written in 1958 about a Riviera hotel-keeper who spends a year preparing to kill his wife; try The Widow, published, like The Outsider, in 1942, and at least equal to Camus’s work in portraying a doomed and alienated life; and above all be sure to read Dirty Snow, a story of petty crime and killing at a time of collaboration in a country that remains unnamed, but which is always taken to be France under the Nazis.

Because he was foolish enough in an interview to claim to have slept with 10,000 women – the real figure, said his third wife rather crisply, was nearer 1,200 – Simenon has sometimes been accused of misogyny, just as by allowing films to be made of his books at the Berlin-supervised Continental Studios in Vichy France during the war, he was also accused of collaboration. The charge of misogyny at least is unfair. A small man’s fear of women is often his subject, and he describes that fear with his usual pitiless accuracy. In his books, casual sex is fine – it may or may not be satisfying – but passion is always dangerous because it arouses feelings neither party can control – and loss of control is seen to be a particularly masculine terror. In these circumstances, sex comes closer to despair than to joy. The women he portrays are not usually manipulative or cruel or deceitful. Far from it. They simply possess an inadvertent power to disturb men and to drive them mad. They exercise this power more often in spite of themselves than deliberately. All of his books are, in one way or another, about power of different kinds, and he specialises in depicting the lives of those near the bottom of society, the concierges and the salespeople, the waiters and the clerks, who possess very little. No wonder, when he went to America, that he remarked how everyone was expected to have a hobby, so that in one small field at least they might exercise at least a measure of domination.

The inspiration for finally deciding to write a play from Simenon came from my friend Bill Nighy, who knew that I was a fan. He gave me a present of a rare first edition of a novel that had been almost entirely forgotten. Even now, I have yet to meet anyone in Britain who claims to have read La Main. In Moura Budberg’s translation, long out of print, the book had been published as The Man on the Bench in the Barn. It was written in 1968, but its atmosphere clearly derived from Simenon’s own period of residence in Connecticut, where he moved to live with his new wife, Denyse Ouimet, in the late 1940s. In the book, the town he then lived in, Lakeville, is renamed Brentwood. His house, Shadow Rock Farm, becomes fictionally Yellow Rock Farm. But the topography and feel of the place are pretty much identical, with beavers playing in a nearby stream, and the local Connecticut community expecting strong but already threatened standards of private morality. The only detail omitted was Simenon’s own telephone number: Hemlock 5.

Sun 25 Sep 2016

Like many bookish children, I grew up consuming detective fiction more than any other kind. Even then I had noticed that stories supposedly driven by narrative depended for their real vitality on establishing ambience. Crime writing came to life when it had density, when you felt that the paint was being laid on thick. A strong sense of time and place was far more exciting than a clever puzzle. Anyone could create a mystery, but only the best could summon up a world in which the mystery could take root.

My taste in literary fiction – I read every word of Patrick Hamilton and Graham Greene – was towards those authors whose techniques most closely resembled those of thriller writers. When, at university, I came across WH Auden’s suggestion that Raymond Chandler’s books “should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art”, I was bewildered. It had never occurred to me that thrillers were anything less. By then I had already graduated from Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers to Dashiell Hammett and the chill ambiguity of Patricia Highsmith. But when I discovered that the author of the Maigret series – which I knew chiefly through the BBC television series with Rupert Davies – was also the author of stand-alone novels, my expectations of the genre changed and expanded. These books belonged more alongside Camus and Sartre than Arthur Conan Doyle. The popular joke in Le Canard enchaîné that “M Simenon makes his living by killing someone every month and then discovering the murderer” seemed nothing more than that. A joke.

It’s symptomatic of our misunderstanding of the unique Georges Simenon that so many people believe he was French. In fact, he was Belgian, born in Liège in 1903 and brought up in a poorly defined country that had often suffered under occupation. In Belgium, few people fostered illusions about national greatness. “Under occupation,” he wrote, “your overwhelming concern is with what you will eat.” Simenon’s background, and his lifelong feeling that he was disliked by his mother, left him with the aim of developing, equally as a writer and as a man, a wholly undeluded view of life. As he later observed: “It must be great to belong to a group, a nation, a class. It would give you a feeling of superiority. If you’re alone you’re not superior to anyone.” Or as he put it rather more bitterly: “During earthquakes and wars and floods and shipwrecks you see a love between men that you don’t see at any other time.”

In fact, he could hardly have been less French. What Frenchman or woman would speak of their loathing of gastronomy – “all that terrible fussing about what you eat”? What French writer or politician would agree that “every ideal ends in a fierce struggle against those who do not share it?” Simenon was particularly horrified by Charles de Gaulle’s pretence that the French had won the war. The untruth offended him. Simenon believed the events of the 1930s and 40s had defeated the French as thoroughly as they had the Germans. “I’ve ceased to believe in evil, only in illness. Nixon believes he’s the champion of the United States, De Gaulle the rebuilder of France. Yet nobody locks them up. Those who invent morals, who define them and impose them, end up believing in them. We’re all hopeless prisoners of what we choose to believe.”

Simenon, not prone to grand literary statements, once said that he wanted to write like Sophocles or Euripides. Over and again, he describes someone quietly living their life, until some random fait divers – a road accident, a heart attack, an inheritance – brings out a fatal element in their character that trips them up. Striking out towards freedom, they fall instead into captivity. He had the idea that a book, like a Greek tragedy, should be experienced in a single session. “You can’t see a tragedy in more than one sitting.” Serial killers, soon to become the thundering cliches of modern drama, whether speaking Danish, Swedish or English, would have held no appeal for Simenon precisely because they are, by definition, extraordinary – and considerably less common in life than on television. Typically, in one of Simenon’s stories, a single crime is enough to ensure that a hitherto normal life falls apart, with no notice, as though any of us might at any time suddenly encounter a crisis that we will turn out to be powerless to overcome.

The thrill of reading a novel, said Simenon, is to “look through the keyhole to see if other people have the same feelings and instincts you do”. The man who, when adolescent, says he suffered physical pain at the idea that there could be so many women who would escape him, has the intense focus of a voyeur. An ex-journalist, he often describes towns from their canals or railway lines, because from there you could look into the back of residents’ lives and not be deceived by the front. He may have said “Other people collect stamps, I collect human beings”, but remarkably he refuses at all times to pass judgment on anyone. “You will find no priests in my work!” Not only does Simenon take care to exclude politics, religion, history and philosophy from his character’s dialogue and thoughts, but the deadpan flatness of his prose style and his bare-bone vocabulary create a disturbing absence of moral control. “Fifty years ago people had answers, now they don’t.”

It was this fallen universe of compromise that I found so convincing when I was growing up. It matched what I had already seen of life. I knew at first hand that Simenon was right when he said that “the criminal is often less guilty than his victim”. But it was only when I was older that I became addicted to the hard stuff – the unsparing novels that take his fatalistic view to its ultimate. If, as is generally thought, Simenon wrote around 400 books, then about 117 are serious novels, the romans durs that meant most to him. André Gide, one of his many literary admirers, when asked which of Simenon’s books a beginner should read first, famously replied: “All of them.” But to my own taste, Simenon’s most searching work came out of his queasy, compromised time in occupied France, and in his desperate hunt thereafter for personal happiness in heavy-drinking exile in the US. If you want to read three of his greatest books, try the deceptively light Sunday, written in 1958 about a Riviera hotel-keeper who spends a year preparing to kill his wife; try The Widow, published, like The Outsider, in 1942, and at least equal to Camus’s work in portraying a doomed and alienated life; and above all be sure to read Dirty Snow, a story of petty crime and killing at a time of collaboration in a country that remains unnamed, but which is always taken to be France under the Nazis.

Because he was foolish enough in an interview to claim to have slept with 10,000 women – the real figure, said his third wife rather crisply, was nearer 1,200 – Simenon has sometimes been accused of misogyny, just as by allowing films to be made of his books at the Berlin-supervised Continental Studios in Vichy France during the war, he was also accused of collaboration. The charge of misogyny at least is unfair. A small man’s fear of women is often his subject, and he describes that fear with his usual pitiless accuracy. In his books, casual sex is fine – it may or may not be satisfying – but passion is always dangerous because it arouses feelings neither party can control – and loss of control is seen to be a particularly masculine terror. In these circumstances, sex comes closer to despair than to joy. The women he portrays are not usually manipulative or cruel or deceitful. Far from it. They simply possess an inadvertent power to disturb men and to drive them mad. They exercise this power more often in spite of themselves than deliberately. All of his books are, in one way or another, about power of different kinds, and he specialises in depicting the lives of those near the bottom of society, the concierges and the salespeople, the waiters and the clerks, who possess very little. No wonder, when he went to America, that he remarked how everyone was expected to have a hobby, so that in one small field at least they might exercise at least a measure of domination.

The inspiration for finally deciding to write a play from Simenon came from my friend Bill Nighy, who knew that I was a fan. He gave me a present of a rare first edition of a novel that had been almost entirely forgotten. Even now, I have yet to meet anyone in Britain who claims to have read La Main. In Moura Budberg’s translation, long out of print, the book had been published as The Man on the Bench in the Barn. It was written in 1968, but its atmosphere clearly derived from Simenon’s own period of residence in Connecticut, where he moved to live with his new wife, Denyse Ouimet, in the late 1940s. In the book, the town he then lived in, Lakeville, is renamed Brentwood. His house, Shadow Rock Farm, becomes fictionally Yellow Rock Farm. But the topography and feel of the place are pretty much identical, with beavers playing in a nearby stream, and the local Connecticut community expecting strong but already threatened standards of private morality. The only detail omitted was Simenon’s own telephone number: Hemlock 5.

We hear a lot about Henry James and the Americans’ traditional fascination with Europe. We hear rather less about its opposite. In my view, there is something rare and interesting artistically when a European sensibility engages with American morals. La Main describes America at a point of change, when the suburban world patrolled so brilliantly by writers such as Richard Yates, Sloan Wilson and Patricia Highsmith is about to yield to a newer way of life, theoretically freer but equally treacherous. It was characteristic of Simenon to suspect that sexual liberation might not deliver everything it promised. After all, he doubted most things, except his own writing. But it was even more characteristic of Simenon to be in the right place, as he had been in France and Africa before the war, and at the right time, equipped with a reporter’s calm genius for putting a moment in a bottle.

Monday, 14 January 2019

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)