James Curtis

The New York Times

30 March 2003

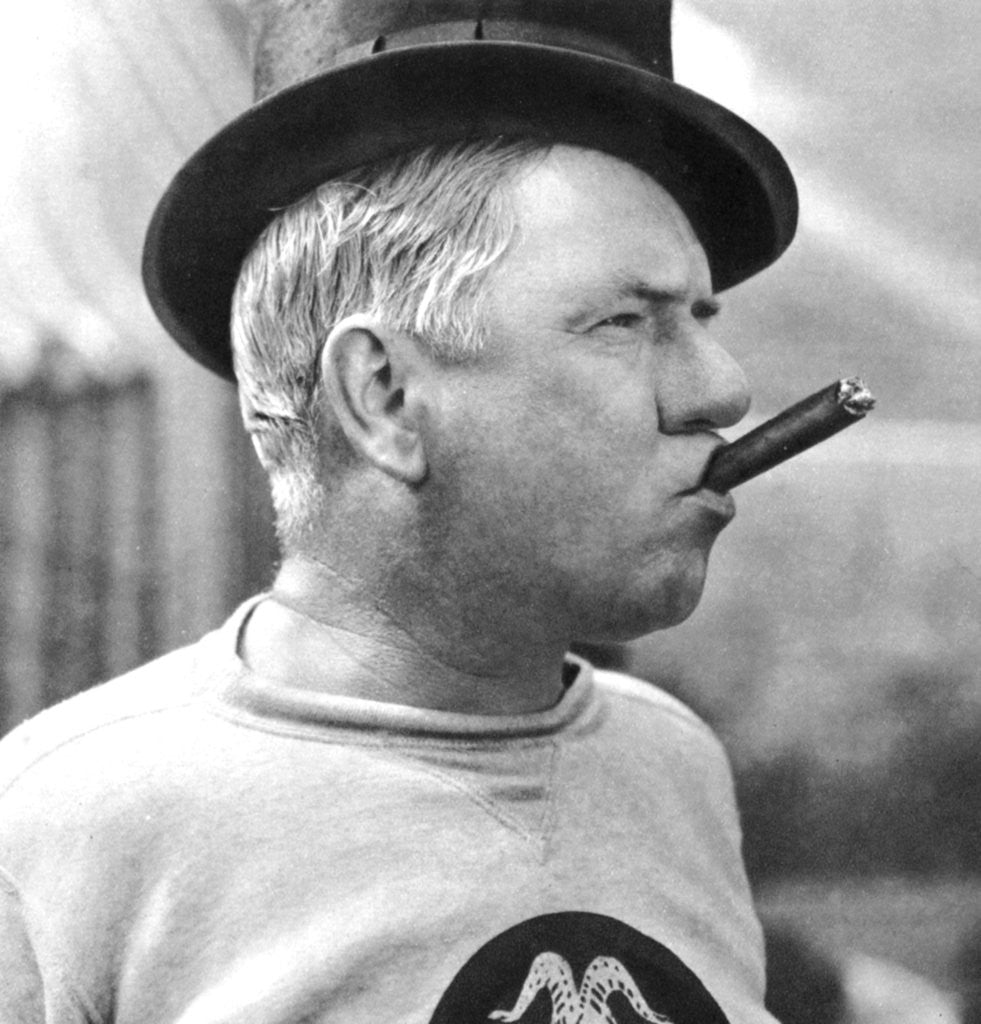

Comedy, Bill Fields would say, is truth-a bit of artful reality, expressed in action or words, carefully exaggerated and brought to a surprise finish. Fields didn't think the mechanics of a gag counted for half as much as the soul behind it. You might coax a laugh from a willing audience over most anything, but a gag wouldn't be memorable without the delight of human recognition.

The comedy Fields propounded reached its apogee with a modest sixty-seven-minute film called It's a Gift. In it, he plays an everyman-hardworking, beset by life's frustrations, caring and respectful of a family that no longer appreciates him. He dreams his dreams in private. He is not brilliant, lovable, or even admirable, but his dignity never leaves him, and, in the end, he triumphs as much through luck as perseverance. When it was released, in November 1934, It's a Gift was a minor event, bound for a quick playoff in what Variety referred to as "the nabes." But the critics took notice, and a groundswell of enthusiasm for the fifty-four-year-old Fields and his work, which had been building for eighteen months, suddenly erupted. Andre Sennwald, writing in the New York Times, referred to Fields' growing legion of fans as "idolaters," and, although not necessarily one himself, he concluded his notice by sweeping away all doubt that one of the great comedies of the so! und era had arrived. "The fact is that Mr. Fields has come back to us again, and It's a Gift automatically becomes the best screen comedy on Broadway."

As Fields pointed out, the appeal of his character was rooted in the characteristics audiences saw in themselves. "You've heard the old legend that it's the little put-upon guy who gets the laughs, but I'm the most belligerent guy on the screen. I'm going to kill everybody. But, at the same time, I'm afraid of everybody-just a great big frightened bully. There's a lot of that in human nature. When people laugh at me, they're laughing at themselves. Or, at least, the next fellow."

Like Mark Twain, Fields believed humor sprang naturally from tragedy, and that it was normal and therefore acceptable to behave badly when things went wrong. One of the key sequences in It's a Gift shows an elderly blind man laying waste to Fields' general store with his cane. Afterward, Fields sends him out into a busy street, where he is almost run down in traffic. "I never saw anything funny that wasn't terrible," Fields said. "If it causes pain, it's funny; if it doesn't, it isn't."

"I was the first comic in world history, so they told me, to pick fights with children. I booted Baby LeRoy. The No-men-they're even worse than the Yes-men-shook their heads and said it would never go; people wouldn't stand for it ... then, in another picture, I kicked a little dog.... The No-men said I couldn't do that either. But I got sympathy both times. People didn't know what the unmanageable baby might do to get even, and they thought the dog might bite me."

The conniving and bibulous character Fields developed caught the public imagination at a time when the nation was deep in the throes of the Great Depression and the sale of liquor was still prohibited by law. He appeared on the scene as the embodiment of public misbehavior, a man not so much at odds with authority as completely oblivious to it. He drank because he enjoyed it and cheated at cards because he was good at it. Fields wasn't a bad sort, but rather a throwback to a time when such behaviors were perfectly innocuous and government wasn't quite so paternalistic. Harold Lloyd called him "the foremost American comedian," and Buster Keaton considered him, along with Charlie Chaplin and Harry Langdon, the greatest of all film comics. "His comedy is unique, original, and side-splitting."

Fields had the courage to cast himself in the decidedly unfavorable light of a bully and a con man. He not only summed up the frustrations of the common man-he did something about them. Unlike most comedians, he never asked to be loved; he was short-tempered, a coward, an outright faker at times. Chaplin was better known, Keaton more technically ambitious, and Laurel and Hardy were certainly more beloved, but Fields resonated with audiences in ways other comics did not. He wasn't a clown; he didn't dress like a tramp or live in the distant world of the London ghetto. Indeed, for most audiences he lived just down the street or around the corner. He was everyone's disagreeable uncle, or the tippling neighbor who warned off the local kids with a golf club. People responded to the honesty of Fields' character because, like Archie Bunker of a later generation, everyone knew somebody just like him. They admired him in a grudging sort of way, and saw the humanity beneath his thick crust of contempt for the world.

"The first thing I remember figuring out for myself was that I wanted to be a definite personality," he said. "I had heard a man say he liked a certain fellow because he was always the same dirty damn so and so. You know, like Larsen in Jack London's Sea Wolf. He was detestable, yet you admired him because he remained true to type. Well, I thought that was a swell idea, so I developed a philosophy of my own: Be your type! I determined that whatever I was, I'd be that, I wouldn't teeter on the fence."

The childhood Fields exaggerated for interviewers was vividly Dickensian, and his run-ins with his father had the brutal energy of Sennett slapstick. Yet the humanity he always strived for in his film treatments failed him when dredging up details of his own early life. He invariably described his father as an abusive scoundrel, his mother as ineffectual and sottish, and his younger self as a Philadelphian version of Huck Finn. He sprang from immigrant stock-his father was British-and however American Fields seemed, there was always an element of the outsider in the characters he played. He embraced the nomadic spirit of his grandfather, whom he never met, and although he was married to the same woman for the entirety of his adult life, he was always at odds with both her and the world, embattled and solitary.

Fields moved through a career that lasted nearly half a century, acquiring slowly the elements of the character by which he is known today. Onstage, he perfected what can best be described as the comedy of frustration, building one of his most popular routines on the petty distractions a golfer encounters while attempting to tee off. His seminal pool act was similarly constructed, leading him to conclude that "the funniest thing a comedian can do is not to do it." In films, he found his voice after an abortive career in silents and became, in the words of James Agee, "the toughest and most warmly human of all screen comedians."

His time as one of Hollywood's top draws was brief-barely six years-and by 1941 his audience had largely abandoned him. Radio, where he could still find work, drained him of any subtlety, due, in large part, to his boozy exchanges with Edgar Bergen's sarcastic dummy, Charlie McCarthy. In spite of his own best efforts, he was constantly at pains to justify a character that had become so fixed in the public mind that he was widely presumed to be the same man he portrayed onscreen. The day he died, Bob Hope made a joke about him on NBC. Hope implied he had seen Fields drunk: "I saw W. C. Fields on the street and waved, and he weaved back." The audience laughed; Fields was by then the most famous drunk in the world. It no longer mattered that he had never played a drunk in his life.

In 1880, travelers approaching Philadelphia from Delaware County and points south would generally pass through the tiny borough of Darby on their way to the Quaker City. Less than a mile square, Darby was a mill town and a transportation hub, home to 1,779 permanent residents and a cluster of paper and textile factories that fairly dominated the landscape. Every day, fifteen thousand workers flooded the town, making the central business district, which ran four blocks along Main Street between Tenth and Mill, second only to Chester in terms of size and importance. There were taprooms and cafs, a funeral parlor, a dozen churches, an Odd Fellows lodge, and one of the oldest free libraries in the nation. Both the B&O and Pennsylvania Railroads passed through Darby, and trolleys connected the Philadelphia line with Wilmington and Chester. Just beyond town were cattle and horse ranches and a vast blanket of farmland that stretched toward Media. Wealthy buyers in search of prime racing stock would put up at the Buttonwood Hotel, at the terminus of the Chester Traction Co. line, or sometimes at the Bluebell Tavern, up near Grays Ferry, where George Washington was said to have stopped on his way to Philadelphia for the second inaugural. Of Darby's several inns, however, only one actually catered to the horse trade-a simple stone building at the southeast corner of Main and Mill Streets known as the Arlington House.

Older than the Buttonwood and less historic than the Bluebell, the Arlington stood directly in front of Griswold's Worsted, the largest and most modern of Darby's numerous textile mills, and a block and a half west of the town dock, the central receiving point for freight and supplies brought up the Delaware River and inland via Cobbs Creek. At the noisiest and dustiest intersection in town, the Arlington was a stopping point for dockhands, mill workers, clerks, tradesmen, and tourists on their way to or from Philadelphia. Atop its three modest stories was a fire lookout, a box- like room with windows on all sides that afforded a panoramic view of the mills along the two tidewater streams, Cobbs Creek on the east and Darby Creek on the west, and the main arteries leading off into Lansdowne, to the north, and Sharon Hill, to the south.

Locals and guests pausing at the bar on the ground floor were likely to be served by James Lydon Dukenfield, a robust Brit in his late thirties who ran the hotel with his wife, Kate, and a cousin from New York named Jim Lester. A short, stocky man with intense blue eyes, a thick moustache, and light hair he carefully parted down the middle, Jim Dukenfield broke Arabian horses for a living and obviously saw an opportunity when the little hotel, built on the site of an old flour mill, came up for lease. He was known for his flash temper, his extemporaneous bursts into song (the more sentimental the better), and the two fingers missing from his left hand. He had a ready smile that made him a congenial host, and an explosive contempt for authority that made him a difficult employee.

Jim had been a volunteer fireman in the days when such companies were like roaming bands of hooligans that would cut the hoses of rival companies for the privilege of knocking down a fire. He enlisted with the Philadelphia Fire Zouaves when the call came for three-year volunteers in August 1861. He deserted for five months-not responding any better to military authority than he had to any other kind-and was mustered out after "accidently" getting his fingers blown off while on picket duty near Fair Oaks. Four of his nine brothers also answered the call, and all survived with the exception of George, two years younger than Jim, who fell at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Jim liked to say he had been wounded at the Battle of Lookout Mountain; his eldest son said he had more likely been caught picking pockets.

Jim Dukenfield was one of thirteen children, most of whom followed their father, John Dukinfield, to the United States in the mid-1850s. John was the second son of George Dukinfield, who in turn was the third son of Lord Dukinfield of Cheshire. John Dukinfield and his elder brother George were born patricians, but the estate passed in line to a grandson who was a clergyman and vicar of the county. When he subsequently died without issue, the estate reverted to the chancery and became property of the kingdom. John moved to Sheffield-not to work in the mines but to distinguish himself as a comb maker, carving premium designs from animal horns. He married an Irish Catholic girl named Ann Lyden and began her career in wholesale motherhood with the birth of their first son, Walter, in 1835. The business grew steadily, and by 1837 John had taken George on as a partner. They established a little factory in Rockingham Street, where they made buttons, spectacle frames, and pocket knives, and installed their families in adjacent housing nearby.

John was a restless spirit, impulsive and autocratic. He had a big nose that would later inspire his niece Emily to remark that his grandson, the film comedian he never met, resembled him "especially above the mouth." In 1854, John was seized with the notion of moving to the United States, where there would be fresh supplies and a ready market for his imitation pearl buttons and tortoiseshell glasses. He packed a trunkful of supplies, enlisted his twelve-year-old son Jim for the trip, and left Ann, pregnant as usual, in George's care. The voyage was arduous, plagued by bad weather, and they were shipwrecked off the coast of Glen Cove, Long Island. John and his son made their way to Dudley, New Jersey, north of Camden, then crossed the Delaware River into Philadelphia, where they opened a dry goods store in the Kensington district, known because of its concentration of British textile workers as "Little England." Ann followed with most of the other kids; Godfrey, the youngest, made the crossing from England in his mother's arms.

The family had largely reassembled by November, when John filed a declaration of intent to become an American citizen. He also began spelling his name "Dukenfield" (with an "en" in place of the "in"), apparently considering this to be an appropriate Americanization of the name. The Dukenfield boys were all fiercely independent-not unlike the old man-and no two spelled the family name alike. According to one source, it derived from "Dug-in-field," meaning "bird-in-field," and there was (and still is) a township in Stockport Parish, near Manchester, called Dukinfield. Jim spelled it with an "en," and other variations included Duckinfield (favored by George as a child), Duckenfield, and even Dutenfield.

The older boys took jobs in and around Philadelphia. Jim, who was good with horses, became a driver. His brother John became a bricklayer, and another brother, George, became a potter. Walter, the eldest, worked as a bartender at the Union Hotel. The family business moved to Girard Avenue, west of Second, and eventually north to 625 Cumberland, where it remained into the 1890s. John Dukenfield opened a tavern on East Norris Street, and it was there that he increasingly spent his time. He managed to drink the business into a downturn, and, in 1859, with six children under the age of ten still living at home, he abandoned his wife and family. Ann struggled mightily with the business, eventually passing it to her brother-in-law George.

Excerpted from W. C. Fields by James Curtis Copyright © 2003 by James Curtis

Comedy, Bill Fields would say, is truth-a bit of artful reality, expressed in action or words, carefully exaggerated and brought to a surprise finish. Fields didn't think the mechanics of a gag counted for half as much as the soul behind it. You might coax a laugh from a willing audience over most anything, but a gag wouldn't be memorable without the delight of human recognition.

The comedy Fields propounded reached its apogee with a modest sixty-seven-minute film called It's a Gift. In it, he plays an everyman-hardworking, beset by life's frustrations, caring and respectful of a family that no longer appreciates him. He dreams his dreams in private. He is not brilliant, lovable, or even admirable, but his dignity never leaves him, and, in the end, he triumphs as much through luck as perseverance. When it was released, in November 1934, It's a Gift was a minor event, bound for a quick playoff in what Variety referred to as "the nabes." But the critics took notice, and a groundswell of enthusiasm for the fifty-four-year-old Fields and his work, which had been building for eighteen months, suddenly erupted. Andre Sennwald, writing in the New York Times, referred to Fields' growing legion of fans as "idolaters," and, although not necessarily one himself, he concluded his notice by sweeping away all doubt that one of the great comedies of the so! und era had arrived. "The fact is that Mr. Fields has come back to us again, and It's a Gift automatically becomes the best screen comedy on Broadway."

As Fields pointed out, the appeal of his character was rooted in the characteristics audiences saw in themselves. "You've heard the old legend that it's the little put-upon guy who gets the laughs, but I'm the most belligerent guy on the screen. I'm going to kill everybody. But, at the same time, I'm afraid of everybody-just a great big frightened bully. There's a lot of that in human nature. When people laugh at me, they're laughing at themselves. Or, at least, the next fellow."

Like Mark Twain, Fields believed humor sprang naturally from tragedy, and that it was normal and therefore acceptable to behave badly when things went wrong. One of the key sequences in It's a Gift shows an elderly blind man laying waste to Fields' general store with his cane. Afterward, Fields sends him out into a busy street, where he is almost run down in traffic. "I never saw anything funny that wasn't terrible," Fields said. "If it causes pain, it's funny; if it doesn't, it isn't."

"I was the first comic in world history, so they told me, to pick fights with children. I booted Baby LeRoy. The No-men-they're even worse than the Yes-men-shook their heads and said it would never go; people wouldn't stand for it ... then, in another picture, I kicked a little dog.... The No-men said I couldn't do that either. But I got sympathy both times. People didn't know what the unmanageable baby might do to get even, and they thought the dog might bite me."

The conniving and bibulous character Fields developed caught the public imagination at a time when the nation was deep in the throes of the Great Depression and the sale of liquor was still prohibited by law. He appeared on the scene as the embodiment of public misbehavior, a man not so much at odds with authority as completely oblivious to it. He drank because he enjoyed it and cheated at cards because he was good at it. Fields wasn't a bad sort, but rather a throwback to a time when such behaviors were perfectly innocuous and government wasn't quite so paternalistic. Harold Lloyd called him "the foremost American comedian," and Buster Keaton considered him, along with Charlie Chaplin and Harry Langdon, the greatest of all film comics. "His comedy is unique, original, and side-splitting."

Fields had the courage to cast himself in the decidedly unfavorable light of a bully and a con man. He not only summed up the frustrations of the common man-he did something about them. Unlike most comedians, he never asked to be loved; he was short-tempered, a coward, an outright faker at times. Chaplin was better known, Keaton more technically ambitious, and Laurel and Hardy were certainly more beloved, but Fields resonated with audiences in ways other comics did not. He wasn't a clown; he didn't dress like a tramp or live in the distant world of the London ghetto. Indeed, for most audiences he lived just down the street or around the corner. He was everyone's disagreeable uncle, or the tippling neighbor who warned off the local kids with a golf club. People responded to the honesty of Fields' character because, like Archie Bunker of a later generation, everyone knew somebody just like him. They admired him in a grudging sort of way, and saw the humanity beneath his thick crust of contempt for the world.

"The first thing I remember figuring out for myself was that I wanted to be a definite personality," he said. "I had heard a man say he liked a certain fellow because he was always the same dirty damn so and so. You know, like Larsen in Jack London's Sea Wolf. He was detestable, yet you admired him because he remained true to type. Well, I thought that was a swell idea, so I developed a philosophy of my own: Be your type! I determined that whatever I was, I'd be that, I wouldn't teeter on the fence."

The childhood Fields exaggerated for interviewers was vividly Dickensian, and his run-ins with his father had the brutal energy of Sennett slapstick. Yet the humanity he always strived for in his film treatments failed him when dredging up details of his own early life. He invariably described his father as an abusive scoundrel, his mother as ineffectual and sottish, and his younger self as a Philadelphian version of Huck Finn. He sprang from immigrant stock-his father was British-and however American Fields seemed, there was always an element of the outsider in the characters he played. He embraced the nomadic spirit of his grandfather, whom he never met, and although he was married to the same woman for the entirety of his adult life, he was always at odds with both her and the world, embattled and solitary.

Fields moved through a career that lasted nearly half a century, acquiring slowly the elements of the character by which he is known today. Onstage, he perfected what can best be described as the comedy of frustration, building one of his most popular routines on the petty distractions a golfer encounters while attempting to tee off. His seminal pool act was similarly constructed, leading him to conclude that "the funniest thing a comedian can do is not to do it." In films, he found his voice after an abortive career in silents and became, in the words of James Agee, "the toughest and most warmly human of all screen comedians."

His time as one of Hollywood's top draws was brief-barely six years-and by 1941 his audience had largely abandoned him. Radio, where he could still find work, drained him of any subtlety, due, in large part, to his boozy exchanges with Edgar Bergen's sarcastic dummy, Charlie McCarthy. In spite of his own best efforts, he was constantly at pains to justify a character that had become so fixed in the public mind that he was widely presumed to be the same man he portrayed onscreen. The day he died, Bob Hope made a joke about him on NBC. Hope implied he had seen Fields drunk: "I saw W. C. Fields on the street and waved, and he weaved back." The audience laughed; Fields was by then the most famous drunk in the world. It no longer mattered that he had never played a drunk in his life.

In 1880, travelers approaching Philadelphia from Delaware County and points south would generally pass through the tiny borough of Darby on their way to the Quaker City. Less than a mile square, Darby was a mill town and a transportation hub, home to 1,779 permanent residents and a cluster of paper and textile factories that fairly dominated the landscape. Every day, fifteen thousand workers flooded the town, making the central business district, which ran four blocks along Main Street between Tenth and Mill, second only to Chester in terms of size and importance. There were taprooms and cafs, a funeral parlor, a dozen churches, an Odd Fellows lodge, and one of the oldest free libraries in the nation. Both the B&O and Pennsylvania Railroads passed through Darby, and trolleys connected the Philadelphia line with Wilmington and Chester. Just beyond town were cattle and horse ranches and a vast blanket of farmland that stretched toward Media. Wealthy buyers in search of prime racing stock would put up at the Buttonwood Hotel, at the terminus of the Chester Traction Co. line, or sometimes at the Bluebell Tavern, up near Grays Ferry, where George Washington was said to have stopped on his way to Philadelphia for the second inaugural. Of Darby's several inns, however, only one actually catered to the horse trade-a simple stone building at the southeast corner of Main and Mill Streets known as the Arlington House.

Older than the Buttonwood and less historic than the Bluebell, the Arlington stood directly in front of Griswold's Worsted, the largest and most modern of Darby's numerous textile mills, and a block and a half west of the town dock, the central receiving point for freight and supplies brought up the Delaware River and inland via Cobbs Creek. At the noisiest and dustiest intersection in town, the Arlington was a stopping point for dockhands, mill workers, clerks, tradesmen, and tourists on their way to or from Philadelphia. Atop its three modest stories was a fire lookout, a box- like room with windows on all sides that afforded a panoramic view of the mills along the two tidewater streams, Cobbs Creek on the east and Darby Creek on the west, and the main arteries leading off into Lansdowne, to the north, and Sharon Hill, to the south.

Locals and guests pausing at the bar on the ground floor were likely to be served by James Lydon Dukenfield, a robust Brit in his late thirties who ran the hotel with his wife, Kate, and a cousin from New York named Jim Lester. A short, stocky man with intense blue eyes, a thick moustache, and light hair he carefully parted down the middle, Jim Dukenfield broke Arabian horses for a living and obviously saw an opportunity when the little hotel, built on the site of an old flour mill, came up for lease. He was known for his flash temper, his extemporaneous bursts into song (the more sentimental the better), and the two fingers missing from his left hand. He had a ready smile that made him a congenial host, and an explosive contempt for authority that made him a difficult employee.

Jim had been a volunteer fireman in the days when such companies were like roaming bands of hooligans that would cut the hoses of rival companies for the privilege of knocking down a fire. He enlisted with the Philadelphia Fire Zouaves when the call came for three-year volunteers in August 1861. He deserted for five months-not responding any better to military authority than he had to any other kind-and was mustered out after "accidently" getting his fingers blown off while on picket duty near Fair Oaks. Four of his nine brothers also answered the call, and all survived with the exception of George, two years younger than Jim, who fell at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Jim liked to say he had been wounded at the Battle of Lookout Mountain; his eldest son said he had more likely been caught picking pockets.

Jim Dukenfield was one of thirteen children, most of whom followed their father, John Dukinfield, to the United States in the mid-1850s. John was the second son of George Dukinfield, who in turn was the third son of Lord Dukinfield of Cheshire. John Dukinfield and his elder brother George were born patricians, but the estate passed in line to a grandson who was a clergyman and vicar of the county. When he subsequently died without issue, the estate reverted to the chancery and became property of the kingdom. John moved to Sheffield-not to work in the mines but to distinguish himself as a comb maker, carving premium designs from animal horns. He married an Irish Catholic girl named Ann Lyden and began her career in wholesale motherhood with the birth of their first son, Walter, in 1835. The business grew steadily, and by 1837 John had taken George on as a partner. They established a little factory in Rockingham Street, where they made buttons, spectacle frames, and pocket knives, and installed their families in adjacent housing nearby.

John was a restless spirit, impulsive and autocratic. He had a big nose that would later inspire his niece Emily to remark that his grandson, the film comedian he never met, resembled him "especially above the mouth." In 1854, John was seized with the notion of moving to the United States, where there would be fresh supplies and a ready market for his imitation pearl buttons and tortoiseshell glasses. He packed a trunkful of supplies, enlisted his twelve-year-old son Jim for the trip, and left Ann, pregnant as usual, in George's care. The voyage was arduous, plagued by bad weather, and they were shipwrecked off the coast of Glen Cove, Long Island. John and his son made their way to Dudley, New Jersey, north of Camden, then crossed the Delaware River into Philadelphia, where they opened a dry goods store in the Kensington district, known because of its concentration of British textile workers as "Little England." Ann followed with most of the other kids; Godfrey, the youngest, made the crossing from England in his mother's arms.

The family had largely reassembled by November, when John filed a declaration of intent to become an American citizen. He also began spelling his name "Dukenfield" (with an "en" in place of the "in"), apparently considering this to be an appropriate Americanization of the name. The Dukenfield boys were all fiercely independent-not unlike the old man-and no two spelled the family name alike. According to one source, it derived from "Dug-in-field," meaning "bird-in-field," and there was (and still is) a township in Stockport Parish, near Manchester, called Dukinfield. Jim spelled it with an "en," and other variations included Duckinfield (favored by George as a child), Duckenfield, and even Dutenfield.

The older boys took jobs in and around Philadelphia. Jim, who was good with horses, became a driver. His brother John became a bricklayer, and another brother, George, became a potter. Walter, the eldest, worked as a bartender at the Union Hotel. The family business moved to Girard Avenue, west of Second, and eventually north to 625 Cumberland, where it remained into the 1890s. John Dukenfield opened a tavern on East Norris Street, and it was there that he increasingly spent his time. He managed to drink the business into a downturn, and, in 1859, with six children under the age of ten still living at home, he abandoned his wife and family. Ann struggled mightily with the business, eventually passing it to her brother-in-law George.

Excerpted from W. C. Fields by James Curtis Copyright © 2003 by James Curtis

Buy the book!!!!

No comments:

Post a Comment