Mark Rothko,No. 4 (Yellow, Black, Orange on Yellow/ Untitled), 1953

There hasn’t been a major group show of Abstract Expressionism in Europe since 1959

Works by Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and other artists are being exhibited together for the first time in 57 years. What do we gain from seeing these works as a group?

Holly Williams

The Independent

Thursday 22 September 2016

In 1959, New York’s Museum of Modern Art sent an exhibition to eight European cities – concluding at London’s Tate gallery – with the calmly self-assured title of The New American Painting. It featured 17 artists, most of whom were associated with Abstract Expressionism, including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still.

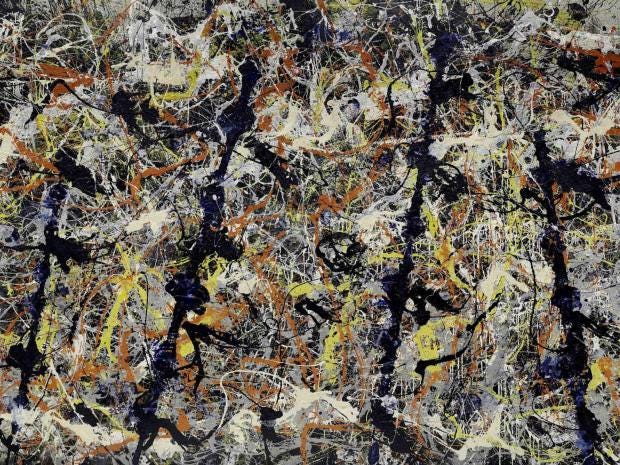

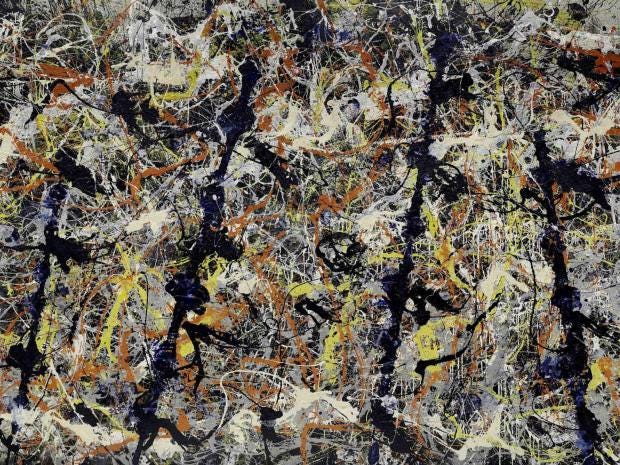

Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952

While critical reactions on the continent veered between stunned admiration and outrage at this show of large, bold, abstract works (one French critic asked: “Why do they think they are artists?”), the mood back in New York was one of jubilant triumph. Abstract Expressionism had proved itself.

They were right to feel confident: Abstract Expressionism went on to be one of the most widely known movements of 21st century art. Pollock and his paint splatters are practically proverbial today. Yet – astonishingly – there hasn’t been a major group show of these artists in Europe since that touring blockbuster.

That changes this week, when the Royal Academy in London brings together works by both core and more peripheral artists for a new group show called simply Abstract Expressionism. While many of the individual artists have had substantial solo shows in the UK over the years, this offers a rare chance to consider their work together, to allow their paintings to really speak to each other.

“This is a group exhibition because Abstract Expressionism was a group phenomenon, involving painters, sculptors and photographers and stretching from New York City to the West Coast,” says Dr David Anfam, art historian and co-curator of the show, who adds that, given it is 57 years since the last group show, “the time is ripe to do this at the RA”.

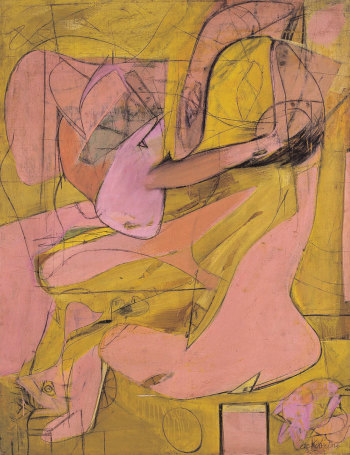

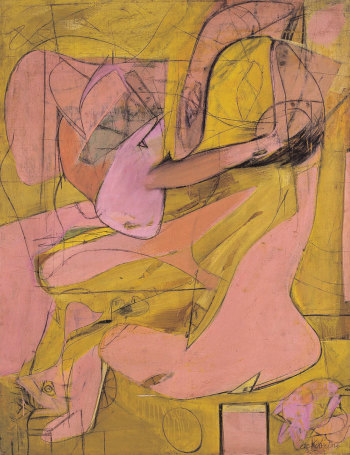

Willem De Kooning, Woman II, 1952

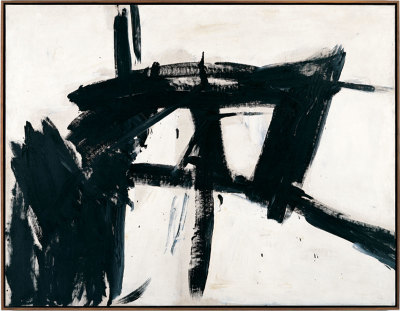

Abstract Expressionism was never a self-defined movement; while many of the artists knew each other well, they had no manifesto like, say, the Futurists. The work is varied: De Kooning’s frantic, grotesque Woman paintings don’t appear to have much in common with, for instance, Newman’s more minimal, soothing “zip” canvasses.

Still, you can say that, starting in 1940s New York, a coherent group of artists began to produce work of a certain vitality, scale and urgency. Whether through intense fields of colour or dynamic drips, slashes and splashes, these abstractions sought to express a human truth, and to elicit a powerful emotional response in the viewer.

As Rothko asserted: “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on – and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions.”

Showing these artists together will demonstrate the breadth of work that falls under the Abstract Expressionism banner, and the show has a revisionist side, paying attention to overlooked artists – women especially – and including photography, works on paper and sculpture as well as monumental paintings.

Willem de Kooning,Pink Angels, 1945

Thursday 22 September 2016

In 1959, New York’s Museum of Modern Art sent an exhibition to eight European cities – concluding at London’s Tate gallery – with the calmly self-assured title of The New American Painting. It featured 17 artists, most of whom were associated with Abstract Expressionism, including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still.

Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952

While critical reactions on the continent veered between stunned admiration and outrage at this show of large, bold, abstract works (one French critic asked: “Why do they think they are artists?”), the mood back in New York was one of jubilant triumph. Abstract Expressionism had proved itself.

They were right to feel confident: Abstract Expressionism went on to be one of the most widely known movements of 21st century art. Pollock and his paint splatters are practically proverbial today. Yet – astonishingly – there hasn’t been a major group show of these artists in Europe since that touring blockbuster.

That changes this week, when the Royal Academy in London brings together works by both core and more peripheral artists for a new group show called simply Abstract Expressionism. While many of the individual artists have had substantial solo shows in the UK over the years, this offers a rare chance to consider their work together, to allow their paintings to really speak to each other.

“This is a group exhibition because Abstract Expressionism was a group phenomenon, involving painters, sculptors and photographers and stretching from New York City to the West Coast,” says Dr David Anfam, art historian and co-curator of the show, who adds that, given it is 57 years since the last group show, “the time is ripe to do this at the RA”.

Willem De Kooning, Woman II, 1952

Abstract Expressionism was never a self-defined movement; while many of the artists knew each other well, they had no manifesto like, say, the Futurists. The work is varied: De Kooning’s frantic, grotesque Woman paintings don’t appear to have much in common with, for instance, Newman’s more minimal, soothing “zip” canvasses.

Still, you can say that, starting in 1940s New York, a coherent group of artists began to produce work of a certain vitality, scale and urgency. Whether through intense fields of colour or dynamic drips, slashes and splashes, these abstractions sought to express a human truth, and to elicit a powerful emotional response in the viewer.

As Rothko asserted: “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on – and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions.”

Showing these artists together will demonstrate the breadth of work that falls under the Abstract Expressionism banner, and the show has a revisionist side, paying attention to overlooked artists – women especially – and including photography, works on paper and sculpture as well as monumental paintings.

Willem de Kooning,Pink Angels, 1945

But, crucially, it should also allow the artworks to connect, to hum and resonate with each other. The exhibition is deliberately organised to reveal lines of influence and aesthetic assonance in a group of artists who, as Anfam explains, “were often very much aware of each other, socially and artistically”.

“By showing the artists together it is possible to establish new sight lines and experiences – for instance, connecting Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt, who were both involved, in their different ways, with developing extremes of colour and similar visual absolutes,” he continues. “Throughout, the curatorial premise is to put the various works in dialogue with each other: Arshile Gorky leading on to his disciple de Kooning, [David] Smith with Pollock, and Pollock himself with his wife Lee Krasner.”

There are rooms devoted solely to Still and to Rothko – but they adjoin each other, with the curators hoping it will be “possible to make visual connections between the two artists for those who want to do so”. Other rooms are thematic: one, entitled Darkness Visible, will bring together works by several of the Abstract Expressionists who, at different points in their careers, “explored the hypnotic power of blackness and shadowy depths of colour”.

Clyfford Still, PH-950, 1950

That there should be artistic overlap is no surprise; although not confined to New York, many Abstract Expressionists lived and worked there in the Forties and Fifties, and would gather in cheap bars and cafés to drink hard, and talk harder.

Gorky, De Kooning, Smith and others would eat at Romany Marie’s, a gloomy little café in Greenwich Village, and afterwards many tables would be commandeered at the seedy Waldorf Cafeteria for heated discussions about art, amid a clientele of cabbies, bums and pickpockets.

At the end of 1949, De Kooning, Kline, Reinhardt and others established The Club in a loft in the East Village; it hosted Wednesday evening discussion groups on lofty topics such as the function of art, and its moral value. Weekends there, however, were for dancing, the alcohol chipped in for by whoever was least broke, and served in paper cups. More booze-fuelled fervent discussion would continue in the cramped Cedar Street Tavern, where Rothko, Newman, Kline, de Kooning and Pollock all would gather.

It’s no wonder artistic influence – not to mention petty jealousies and deeper feuds – spread among them. “It was Clyfford Still who influenced Mark Rothko’s breakthrough into abstraction during the second half of the 1940s,” suggests Anfam. “Some of David Smith’s sculptures also clearly echoed Pollock’s paintings. And Pollock and De Kooning famously became rivals who each vied to be the numero uno, as it were, of the whole group.”

By the mid-Fifties, Abstract Expressionism might have been rising in artistic importance, and in financial value, but the relationships within the loose group were falling apart. Still wrote letters denouncing Rothko’s desire for “bourgeois success”, while Newman also claimed Rothko had stolen from his paintings. Newman tried to sue Reinhardt for publishing a sneering account of him in a satirical piece about the New York art scene, and he and Still also fell out over accusations of copying.

Mark Rothko No. 15, 1957

Hey, no one ever said being part of a major artistic phenomenon would be easy. But given there were such intense relationships, it’s surely surprising that there haven’t been more group shows. Aside from the physical considerations – securing loans of such vast canvasses isn’t easy – why might this be the case?

“Abstract Expressionism was so huge that it soon got taken for granted throughout the art world,” suggests Anfam. With many other, also highly significant, movements rapidly following it – from Pop to Minimalism to Conceptualism – he thinks Abstract Expressionism got somewhat elbowed out of the way.

“Now is the moment to see its breadth and depth afresh. It’s an art of enormous ambition and originality, with which we need to reckon once more.”

Abstract Expressionism is at the Royal Academy in London, 24 September to 2 January

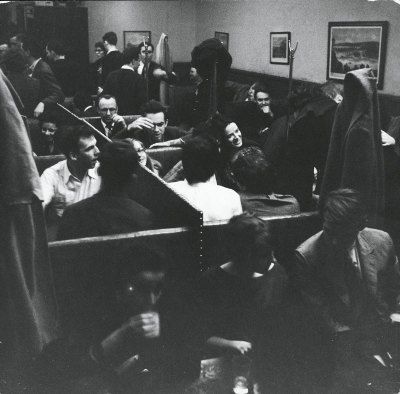

Inside the Cedar Tavern, 1956

New York’s legendary Cedar Tavern and the surrounding galleries became the hub of the New York art scene in the 1940s and ‘50s. Morgan Falconer walks the streets where reputations were on the line

Morgan Falconer

Royal Academy Magazine Autumn, 2016

1 September 2016

One of the frequent complaints of native New Yorkers today is how the city is all the same, and the same as everywhere else. You only have to glance into the lives of the Abstract Expressionists to see that their New York was a different place altogether.

Back then, Barnett Newman could have a loft on Wall Street and remember Manhattan as a “compact heterogeneous cosmopolis”, a place where you could have the “feeling of living in two centuries”. Uptown was 20th century: when the writer Alfred Kazin had lunch on the roof of the Museum of Modern Art, he felt he was “swimming in the reflected surfaces of some great goldfish bowl. New York was gold skin, kaleidoscopic glass.” Downtown was where you found old New York – and the working artists. It was here, in 1934, that Jackson Pollock and his brother Sande moved into an abandoned commercial building sitting among piles of rubble and the shanties of the homeless. It had no heat or running water and visitors had to throw stones at the windows to get their attention.

Norman Bluhm, Joan Mitchell and Franz Kline at the Cedar Tavern, 1957

1 September 2016

One of the frequent complaints of native New Yorkers today is how the city is all the same, and the same as everywhere else. You only have to glance into the lives of the Abstract Expressionists to see that their New York was a different place altogether.

Back then, Barnett Newman could have a loft on Wall Street and remember Manhattan as a “compact heterogeneous cosmopolis”, a place where you could have the “feeling of living in two centuries”. Uptown was 20th century: when the writer Alfred Kazin had lunch on the roof of the Museum of Modern Art, he felt he was “swimming in the reflected surfaces of some great goldfish bowl. New York was gold skin, kaleidoscopic glass.” Downtown was where you found old New York – and the working artists. It was here, in 1934, that Jackson Pollock and his brother Sande moved into an abandoned commercial building sitting among piles of rubble and the shanties of the homeless. It had no heat or running water and visitors had to throw stones at the windows to get their attention.

Norman Bluhm, Joan Mitchell and Franz Kline at the Cedar Tavern, 1957

The young and restless move to cities all the time to slum it while dreaming of moving “uptown” – figuratively or literally. But among the Abstract Expressionists, those who made their breakthroughs in the late 1940s, there were few with such ambitions. The Depression years – when many of that circle came to know each other – taught them to expect little. And the world of contemporary art in New York was tiny, with only a handful of galleries – names like Betty Parsons, Peggy Guggenheim, Samuel Kootz and Sidney Janis. “The public,” as critic John Gruen wrote, “stayed away in droves.” By day the artists would work, by night they would frequent “The Club”, their private talking-shop, or dance in someone’s studio – the tango, the jitterbug, even the kazatsky, the Russian folk dance beloved by Communists and Russophiles in the 1930s.

Jackson Pollock,Male and Female, 1942-43

And they would drink and drink and drink at the Cedar Tavern. In the garrulous man’s world that was New York Abstract Expressionism, reputations were established as much in the Cedar as in the galleries. Situated on West 8th Street during its heyday, it was nothing more than a long, narrow room with brass-studded leatherette booths (pictured above). There was little decor and the clock over the bar sometimes ran backwards; its walls were described as ‘interrogation green’. But for the painter Norman Bluhm (above, with Joan Mitchell and Franz Kline), and many others, it was “the cathedral of American culture in the Fifties.”

Pollock, de Kooning, critics like Harold Rosenberg (below, seen centre talking with Irving Sandler) and Thomas Hess – they all passed through its doors. Kline was a regular. Tormented by his unhappy childhood and his wife’s mental illness, he was remembered as someone who would be there when you arrived and still there when you left. Pollock would bound in on Tuesdays after visiting his psychotherapist and would hunt down Kline, joking with him as much as baiting him. On one occasion, after Kline had admonished Pollock for criticising Philip Guston, Pollock pulled a swinging door off its hinges and hurled it at him.

In the early 1950s, when the market for Abstract Expressionism began to grow, artist-run galleries began to pop up a few blocks away around East 10th Street. Galleries like Hansa, Tanager (shown at top), James and Brata were established as co-operatives, and artists lived and worked around them. The backdrop was dull – pool rooms, an employment agency, a metal-stamping factory – but the mood lively and do-it-yourself. One visitor to a group show in 1951 remembered sheltering from the summer heat under a sign painted by Kline.

Harold Rosenberg (centre) chats to fellow critic Irving Sandler at an exhibition of works by Grace Hartigan, 1959

For the most successful among them, there was also uptown. The better commercial galleries were mostly situated in lavish quarters near Tiffany & Co and Bergdorf Goodman on 57th Street. The dealers often came from rarefied worlds: before opening her gallery, Betty Parsons had been to finishing school and appeared as a debutante in the society circles of Newport and Palm Beach. Bridging this chasm wasn’t always easy for the artists. On one occasion, when Pollock had to head uptown – and dress accordingly – for an uncomfortable meeting, a friend remembered their car coming to rest at a traffic light next to a limousine. Pollock exploded, shouting, “Goddamn sons of bitches, dirty sons of bitches! Goddammit, I can wear a pinstripe suit, too!”

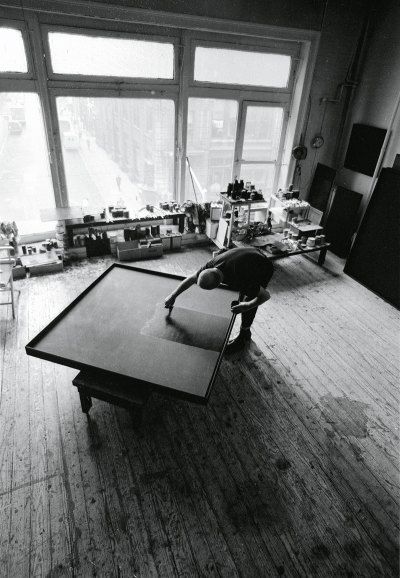

Ad Reinhardt at work on an untitled ‘black’ painting in his studio, New York, 1966

Of course, as Barnett Newman noted, the New York of the 1940s wasn’t just a binary world of uptown and downtown, it was multifarious. Many disliked the Abstract Expressionists’ haunts. The critic Clement Greenberg described the Cedar Tavern as “awful and sordid”; Lee Krasner said the “women were treated like cattle,” and Frank O’Hara, the poet and curator, hated the homophobia. Tellingly, the next generation of New York artists would spring from different circles, and a different part of town. Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist and Robert Indiana lived around Coenties Slip, at the foot of Manhattan, with Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg nearby.

But by the late 1950s, when that new generation was emerging, the Abstract Expressionists were already starting to leave the city. Pollock and his wife Lee Krasner moved out to Springs, a pocket of the Hamptons on Long Island in 1945, as newlyweds; de Kooning followed years later; Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell would also take houses nearby. Today, Springs is just one part of the area’s playground for Manhattan’s business elite; then, it was a remote town of farmers and fisherman where life, de Kooning said, was “kind of biblical.” Pollock’s Long Island studio is preserved to this day, and the paint on the floor has sat there since he worked on canvases like Blue Poles (1952). But much else in the world of those artists has changed. When I took a trip downtown recently, I decided to find out what had become of the Cedar Tavern of Pollock’s day. I walked up and down, struggling with the street numbers until finally I realised that the site of the bar, and much else besides, has been engulfed by a vast, chain-store pharmacy. They do, at least, sell hangover cures.

Abstract Expressionism is in the Main Galleries at the RA from 24 September 2016 – 2 January 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment